Ephraim Asili

BY

Inney Prakash

An interview with the New York-based experimental filmmaker.

The Films of Ephraim Asili streams on Metrograph At Home.

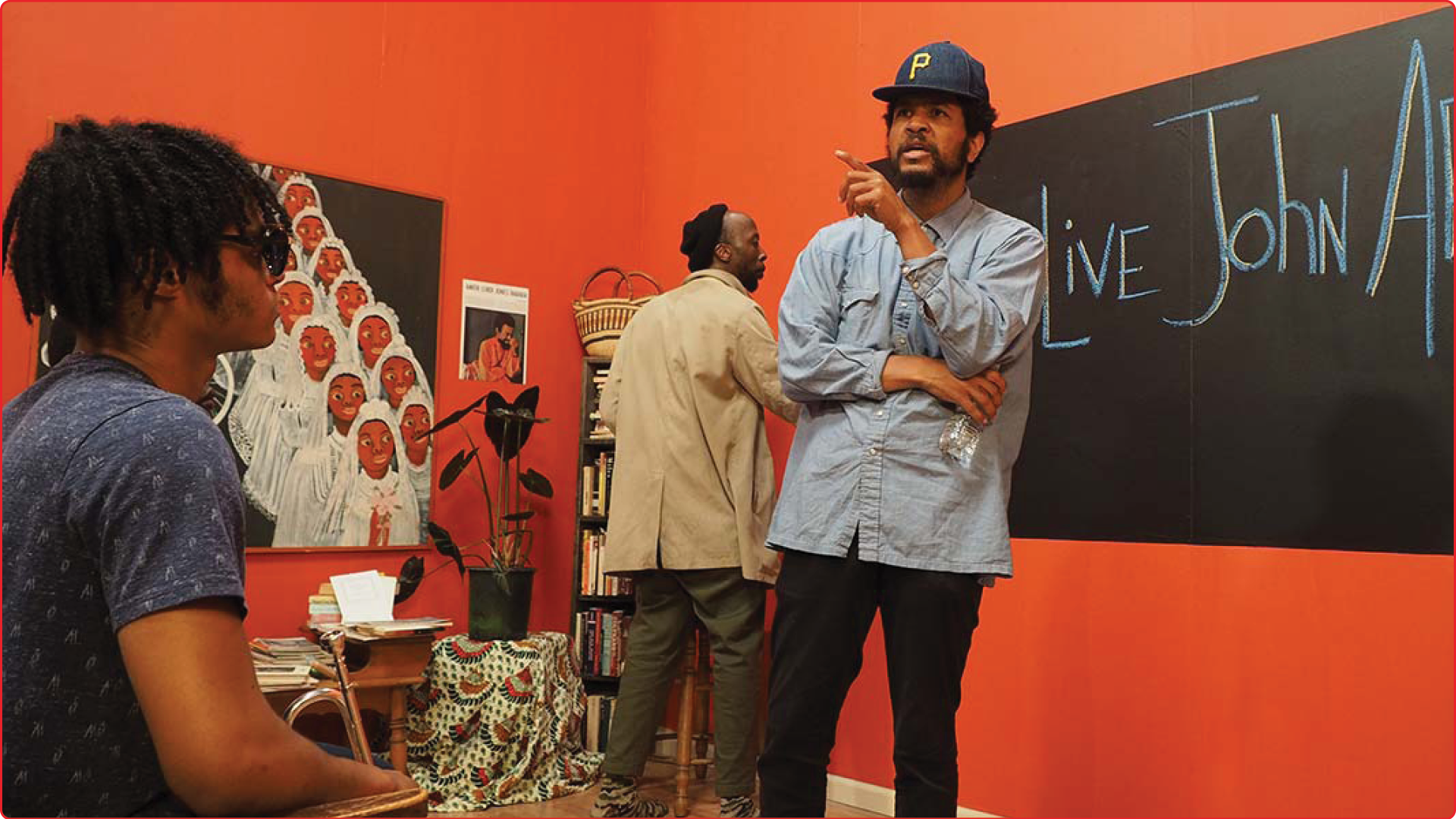

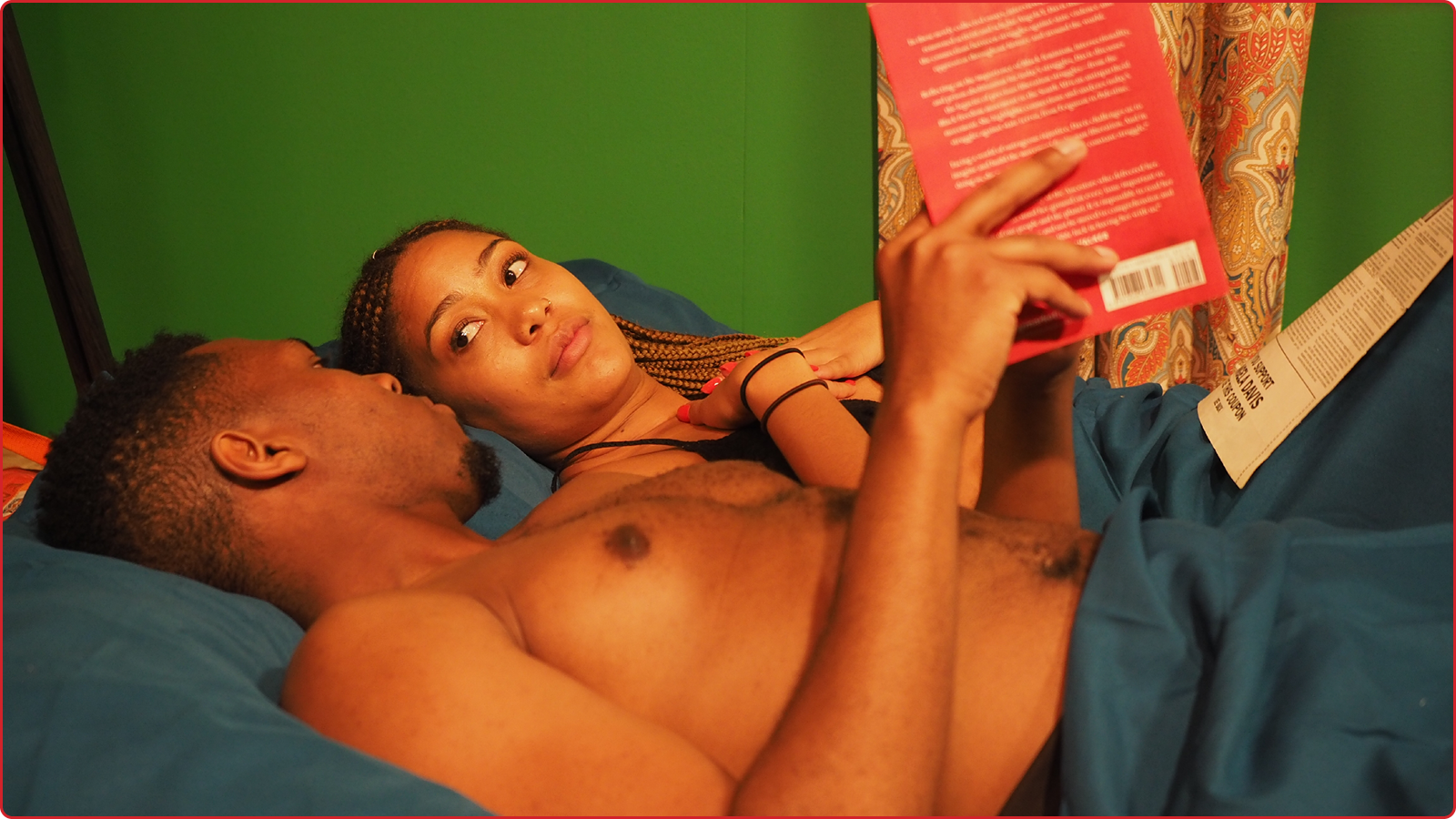

Among the various quotes scrawled at different times on a blackboard in the communal setting of Ephraim Asili’s debut feature film, The Inheritance (2020), is one from the poet and sociologist Calvin C. Hernton: The physical world whirls in its orbit / The spiritual world whirls in its orbit / The orbits of the physical and the spiritual / Are integral whirls. The Black intellectual and artistic histories, as well as the living connections between them, that infuse Asili’s body of work, and the playful aesthetic strategies that animate it, could well be described as integral whirls, stirring space and time to paint a fresh, unbridled and ecstatic Pan-Africanist utopia for the mind’s eye.

In his universe, Black joy in Harlem, Jamaica, and Ghana becomes a shared expression, and intellectual figures and political movements make dialogue across the space-time continuum. Through The Inheritance and his previous series of shorts, dubbed The Diaspora Suite (2010-2017), Asili has established himself as a vital new force of the American avant-garde. Fusing jazz, poetry, and agitprop, his bold and flexible aesthetic sense carries the vitality of analog film across centuries. He spoke with me from his home in upstate New York. Behind him was a record collection to rival any I’ve seen.—Inney Prakash

INNEY PRAKASH: Where are you and what’s going on with you?

EPHRAIM ASILI: I am in Hudson, New York, and I’m a bit scrambled at the moment; I’m in the middle of shooting a feature. And then I’m doing this NFT collaborative project that I just came out of a meeting for. On top of that, to make matters worse, I have a solo show opening in the fall [Song for my Mother at Amant, Williamsburg], this three-channel thing that I’m editing. So it’s all, I wouldn’t say crashing down on me, but it’s a fun juggling act.

IP: That’s interesting to know that NFTs are still alive. But it sounds like a lot of good stuff, congratulations! I read that your filmmaking didn’t begin until your mid-twenties, but I’m curious to know when you first became actively engaged with the idea and history of the Black diaspora, and if Philadelphia was a formative part of that development?

EA: In my films, you get this impression that it’s all about going very far away and connecting, having these, for lack of a better word, exotic experiences. But I grew up very working class. We didn’t travel customarily. We didn’t take summer vacations to other countries. What I did have access to was a diversity of different types of Black people. Later, I had the opportunity to explore some of these connections as a filmmaker.

In my neighborhood growing up, my neighbors across the street were from Jamaica. My best friend’s family were from a certain part of Philly that was culturally a bit different to the suburb I’m from—my parents are from the north, my best friend’s parents are from the south. I was always fascinated by this. Now we say things like “Black people are not a monolith,” though at the time growing up, everything was like “the Black community,” this sort of thing. But I had always found it to be way more multifaceted than what you would see on TV.

In my late teens, when I moved to West Philly, that exploded [for me] because suddenly I’m in a neighborhood where there are people from all over Africa, east and west, central, what have you, as well as the Caribbean. I was always one to go out and explore the neighborhood, eat in different restaurants, talk to people. I always lived in a very diverse environment, where the diaspora was just a type of currency; we all talked about each other’s leaders and history as a way of showing camaraderie.

Also, every now and again, I’d get a little money together, and I would take these trips to Jamaica.

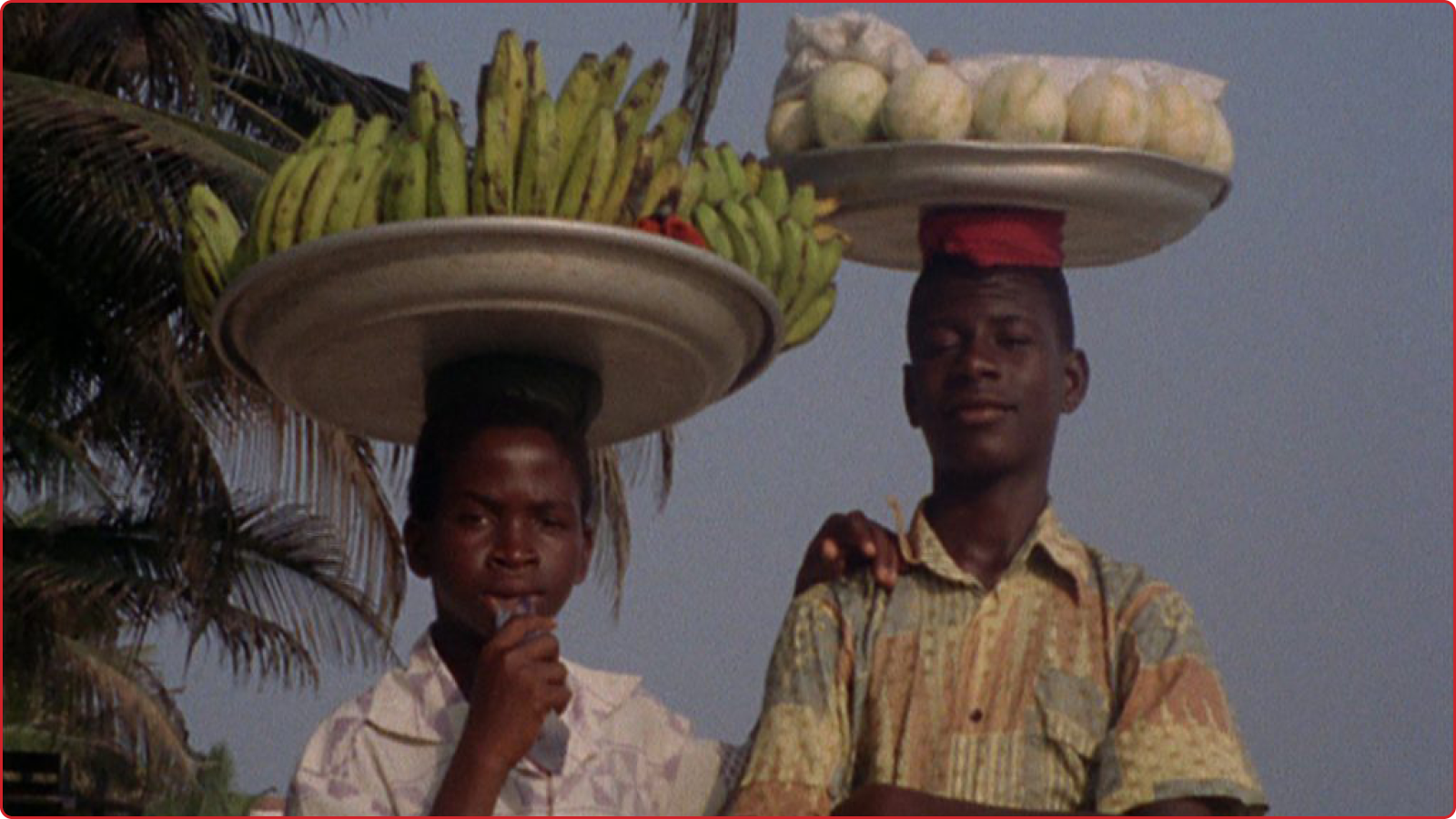

Fluid Frontiers (2017)

IP: Why Jamaica?

EA: Because of Rastafari. Cliché as it is, toward the end of my time in high school I got really into Bob Marley and reggae, and started to take it more and more seriously as a spiritual and political belief system. I got to spend time around different Rastas from Philly, from New York, Brooklyn, and eventually became so interested in it that I would travel to Jamaica to meet other Rastas and learn as much as I could. I made a film in The Diaspora Suite, Kindah (2016), in a village [Accompang] where I’d spend time with other Rastas. I learned a lot about diaspora through my experiences as a Rasta in those days, and taking seriously the call to Pan-Africanism.

IP: Far from exoticizing, whether it’s Jamaica or Ghana or Brazil, what’s interesting in the Suite is the slippage between different sites of diaspora; the way you cut images of these places together creates a unifying experience. Was that an experience you had visiting Jamaica for the first time, one of recognition?

EA: Yes. When I graduated high school, I wasn’t sure what I really wanted to do, but I kind of wanted to be a farmer. It’s something I’d never actually seen, Black people farming. In the context I was growing up in, it seemed maybe obvious to others that was some sort of reference to slavery, or going in the wrong direction; I should aspire to be a doctor or something, not a farmer.

But [my interest] was more natural, simple. From Philly or New York, you could get a cheap flight [to Jamaica]. I knew that if I went there and went out to the mountains, I would experience Black people farming. So, that’s what I did. I was delighted. I felt totally connected.

Everywhere I’ve been, I’ve always been generally welcome. It feels like it’s deeper than my personality, that there’s something on a DNA level. It’s just always felt that way. It’s not intellectual, it’s a feeling based on intuition and lived experience that’s always been there.

IP: Was farming something that fed your interest in collectivity, in terms of the amount of work it takes?

EA: If I think about it now, absolutely. But funnily enough, when I first became interested in this idea it was more about self-reliance: I’ll help my neighbor if my neighbor helps me. Initially, it wasn’t to start a collective or some sort of commune and live on the land, though. It was very much this naïve idea of just wanting to have a family, and a little piece of land. That was the master plan.

IP: Later, you did have that experience, in a collective living experiment in West Philly—which is reflected in The Inheritance.

EA: In Philadelphia, I was engaging with people from the MOVE organization, who were similar to Rastas but had some pretty strong differences. On the level of back to nature and living simply, they had, from my estimation at that time, figured that part out but in an urban environment. So these collective, anarchist ideas started to fuse with my self-interested, self-reliant energy. I ended up forming a collective based on experimenting with these different lifestyles. That’s what led to the window of time I made the film about.

IP: You mentioned MOVE, the legacy of which features prominently in The Inheritance. The bombing of MOVE in 1985 was a horrendous act of state terror, but your film is infused with a certain joyfulness and pleasure. I’m curious about your choice to opt for an aesthetic informed more by playfulness, discovery, and joy than trauma.

EA: Well, the trauma goes without saying, for me in my work and in general. And certain other things that go with trauma go without saying—for me, they don’t need to be addressed directly. There’s elements of play and joy, curiosity, experimentation. These are the solutions to our problems, and it’s something for me as an artist that it’s important to really, really put in the forefront of what I do—which isn’t always fashionable with art, where people want to see a certain amount of pain placed in a certain context.

It’s not so much about avoiding certain issues, but trying to deal with them in ways that might open up new solutions. Creating space where I can play with some of that is really important, which is why I wanted to do a narrative film in the first place. It’s like, there are certain spaces where it’s appropriate to play in this way, and there are others where it is not; I wanted to take these very serious, often traumatic experiences, but place them in a context where they can be looked at differently. One of the great things about comedy is it gives us a different angle. That’s something I’m always trying to go for, but particularly with The Inheritance.

IP: The film is also rife with homages to the ancestors, as you put it. There’s literature, records, and art all over the place, all very beautifully arranged and presented.

EA: Yeah. And I think that relates to this idea of playfulness and joy. For me, my process, it’s very, very simple: I go out into the world and try to actually engage with the communities, environments that interest me, and see what happens. All of the things that you’re seeing in the films, they’re not so much things that I do academic research on and then seek out, it’s often reverse engineered in a sense.

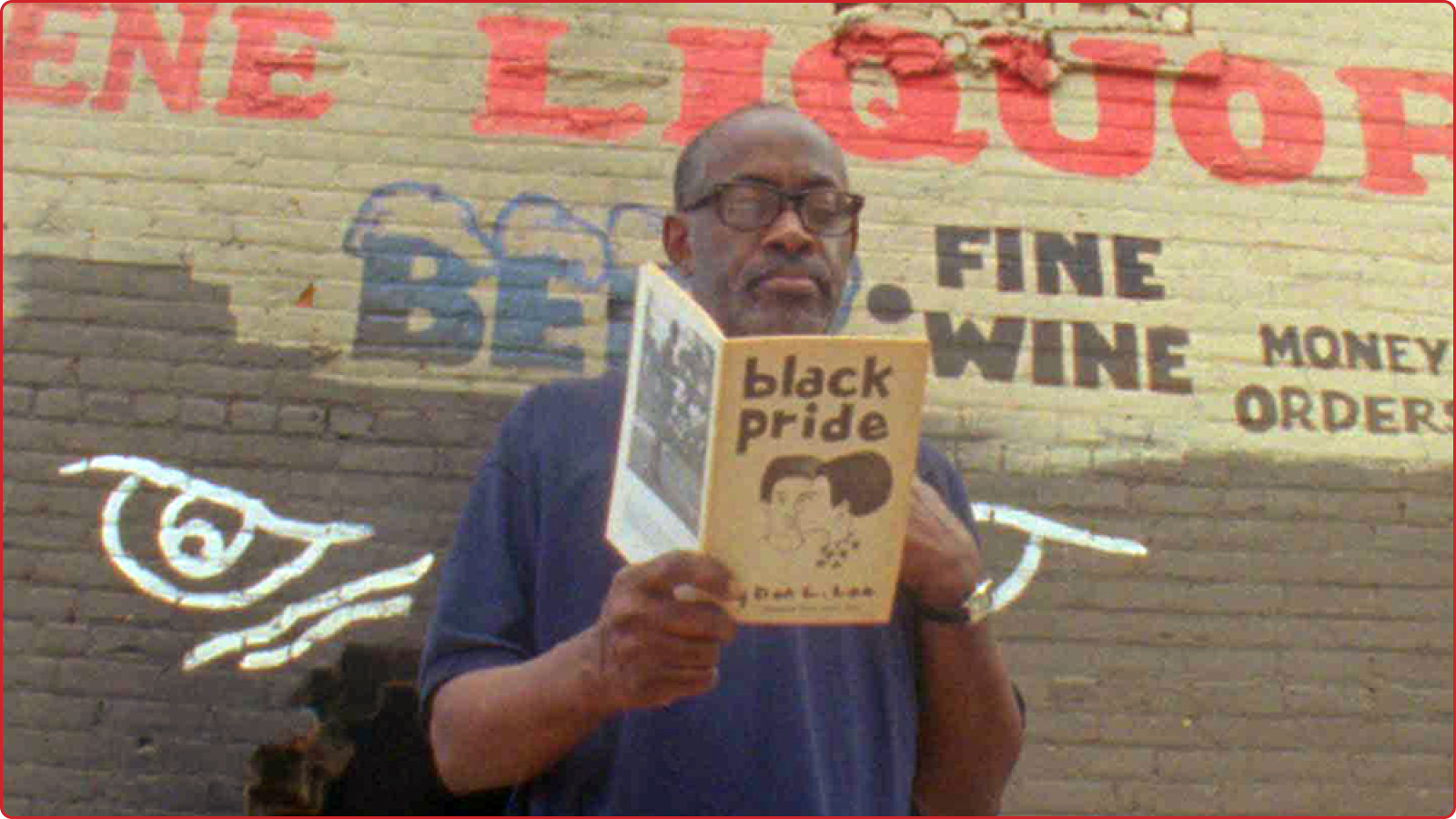

For example, there is a bookstore I frequent in Detroit that led me to make a film called Fluid Frontiers (2017), which is about these Broadside Press books that I bought; it was just being inspired by the bookstore itself. I walked around, things came out. You asked me this question about farming before, and I think in life, I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m more of a hunter than a farmer, and there’s a certain joy in finding these things and filming them and so forth. And that is really the process. Making it make some sort of intellectual sense, or at least making it pose interesting questions, is the work of editing and putting a film together.

The Inheritance (2020)

IP: I assume you’re talking about King Books in Detroit, the four-story used bookstore?

EA: Yes, you know it? It’s a great place.

IP: Yeah, I’m from around Detroit. I actually worked at King Books.

EA: Get out of here! Okay, yeah, in Fluid Frontiers there’s a woman named Deborah who worked there—maybe she still works there, I don’t know—but she reads a poem in my film.

IP: She was my boss.

EA: Oh really? That’s so cool. Small world.

IP: There’s a character in The Inheritance who brings up an interesting point about education, that it’s often educated people who say school is unnecessary. I’m curious about your relationship to that thought—especially now that you’re a professor at Bard.

EA: How about that? I would say that as far as the character, that’s very much that character’s belief. I dropped out. I went to college for a year out of high school and then I left. I didn’t go back in a full-time way until my mid-twenties. But I found that in my activist days living in West Philly, many of the people I encountered did have college degrees and I did not. They seemed to have access to something I didn’t, that I could never quite put my finger on, regardless of the books that I read, etc.

But yeah, they would often say that sort of thing. It’s an interesting piece of dialogue to pick up on, because it really gets to a lot of the thoughts that go on [in my process] in terms of how to write these sorts of lines.

IP: Can you say more about that? Is it a matter of having a conversation with yourself?

EA: Yes, in some ways... But I think that conversation with myself, in the case of this film, was also a result of getting to know my actors fairly well. In writing the dialogue, I’m very much thinking about the person who’s delivering it. And in thinking about that person, I’m thinking about many conversations I’ve had with them… And when we got to the final script, I was pretty much writing for those specific people. When it’s all said and done, [the process] was very solitary, but there are a lot of collective moments prior to that.

IP: There are a lot of explicit references to books and intellectuals and history in The Inheritance, but less so to films. Is that because you feel like you draw influences less from film history, or because it plays less of a role in the life you’re trying to evoke? Or neither?

EA: I would say the references to film operate on a different plane than those other things.

IP: Right. Although I should say there’s a very explicit reference throughout to La Chinoise (1967), the Godard film.

EA: For instance. And that’s happening on such a meta level, that to overload it in another context would take away from the artistry. The film references can be like that—early on, for instance, there’s a reference to Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice (1986), which is his idea of the house burning. I was deliberately inverting that.

Another example, where I had to throw a little bit of potty humor in there, in the scene where the guy is playing his trumpet in the bathroom and then the other character comes out and says, “The bathroom’s for asscoustics only,” there’s a poster [on the wall] of Coonskin (1975), a Ralph Bakshi film. I was trying to insert the idea of a comic strip, something like that. And there are others, if you go through. It’s very personal, that element, and I don’t mind whether people get those references. For the other stuff, I think it’s important references are clear. I wanted the politics to be more direct.

American Hunger (2013)

IP: I’m curious about the didactic elements, and how you see those operating. It occurred to me—and I mean this as a compliment—that in the right context this film could be used as, like, the ultimate afterschool special.

EA: Yeah, I’ll take the ultimate afterschool special! The question for me is always: what does it mean to be didactic? You’re making something very clear, and there’s a reason for that. Like, I need you to understand this right now.

What’s interesting to me is didacticism without urgency. For example, a Black Panther newspaper, which for many people at the time was probably a terrifying thing to look at. This is people killing cops. Whether you’re someone who’s like, “Oh my God, these people are going to kill me,” or you’re like, “Damn, is this what it’s going to take to get my neighborhood together,” it’s a shocking image in its day. It’s not meant to just be cool graphic design.

Flash forward now, and none of that’s there. Those images are terribly didactic and they’re amazingly beautiful works of art in and of themselves, right? That read, I think, was impossible at the time. For me as an artist, when I’m making a sort of didactic statement, it’s about the, I’ll say collage element. When you have something that’s very didactic in a certain moment, and then you cut that against something that’s totally open, what do they say about each other?

IP: It’s interesting to hear the word collage in this context because that relates very directly to the shorts in The Diaspora Suite, which are kind of pure montage, seemingly shot without synced sound, cutting back and forth, sometimes rapidly and unrecognizably between different places—for example in Many Thousands Gone (2015), where you seamlessly transpose purposely shaky, handheld footage of Harlem and Salvador, Brazil. How did you arrive at that aesthetic?

EA: I made the first film in The Diaspora Suite [Forged Ways, 2011] when I was finishing up grad school, it was a thesis project. I had become interested in multi-channel work and creating experiences that don’t feel trapped by the linear nature of cinema.

As a grad student, I was exposed to a lot of different kinds of art and started to gain the ability to think of what I was doing in other terms: how does it function as a sculptural idea? How does it function as a painterly idea? Something I always admire about these other artforms is that the time element is collapsed. I don’t think of painting or sculpture as being non-durational because there’s the amount of time that one spends engaging with them. That takes time. There’s duration involved in the process, but they don’t move in time, right? So, all of the time in a painting is contained in that painting.

With a film, I want to create the energy that you’re getting all of the different types of time at once, that it’s almost like, a flattening effect to make it more two-dimensional. I’m trying to take a durational medium and have it work against the idea of time in some way, which for me, is playing with the space relationship, to kind of collapse space. So like you’re saying, sometimes it’s not discernible where you are. That slippage creates the feeling that you’re existing in two time relationships at the same time.

There’s also this idea of deriving some time relationship by just looking at the labor of a painting or a sculpture, where there’s this durational element to it. I’m trying to get that in film without relying on the duration that it takes to watch the film from start to finish, which I could go on and on about.

IP: I mean, I’m happy for you to! I actually have your book Measuring Time sitting here next to me. Is that the process that you were referring to?

EA: The idea is that, there’s the clock, right, which is like, an idea about time that we all are familiar with. But time as an experience is deeply subjective and not perfectly metered. And music is the best way, I think, to understand this; a drummer might be keeping two, three, four rhythms, possibly in different tempos, all at the same time—which is to say, there can be several times contained within a moment, you know? I’m trying to work with that in film. And for me, the element that allows this sort of polyrhythmic possibility is memory.

If I have one shot of someone smoking a pipe in Jamaica, and then the next shot is just of my back porch, when I’m looking at the porch, I still remember the previous shot. So when I’m editing, I might see how many more shots can I add before I forget about the person smoking the pipe in Jamaica. That window of time, when we’re holding onto an image from a previous scene while watching another, that’s what I mean by a polyrhythm, It’s like one note lingering while another note is being hit.

IP: To finish, let me ask, since you’re a DJ and you’ve got a beautiful record collection behind you. Can you leave readers with one choice recommendation?

EA: What do I have laying around? I’m going to go Roy Ayers, and take it out of the sleeve: Africa, Center of the World. As you can see, there’s a little green Africa [on the cover]. It’s from 1981. This album is dedicated to Pan-Africanism, and actually has Fela Kuti and Fela’s musicians playing on it. I’ll even give you a track: “I’ll Just Keep Trying.” Anyone who’s been to a party of mine will be like, “Oh yeah. If you know Ephie, that’s the one.”

Inney Prakash is a film curator and writer based in New York City.

The Inheritance (2020)