Sudanese Film Group

Sudanese Film Group

Manar Al Hilo, Suliman Elnour, Eltayeb Mahdi, and Ibrahim Shaddad in Talking About Tress (2019)

BY

Lilli Kobler

An interview with Sudanese Film Group co-founders Suliman Elnour, Eltayeb Mahdi, and Ibrahim Shaddad.

Focus on Sudanese Film Group opens In Theatre and At Home August 12.

LILLI KOBLER: I would like to start with when you met for the first time.

ELTAYEB MAHDI: We met in 1977. I had just graduated from the Higher Institute of Cinema in Cairo and came back to Sudan, then Ibrahim returned from Canada. Two years later Suliman came back from the USSR.

SULIMAN ELNOUR: I arrived exactly on March 14, 1979. After a few days Abdurahman Nagdi arrived, and together with Eltayeb, Ibrahim, Manar Al Hilo, and Mohammed Mustafa they visited me at home. From that time until now we have stayed in close contact.

LK: You all studied film abroad, at universities outside of Sudan. How did you come to choose these universities, and how did you experience your time there?

SE: At the end of 1970 I was working at the State Corporation for Cinema. They intended to send two staff members to study film in the Soviet Union. Then came the coup d’état of Hashem al Atta in July 1971, and the relation between Sudan and the Soviet Union was completely stuck. Finally, a year later I left and started to study history at the Patrice Lumamba University in Moscow (today: Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia). After the first year of studying I applied to the VGIK (All-Union State Institute of Cinematography) and I got accepted.

LK: How was the experience in Moscow?

SE: In the ’70s there were great changes across the globe, student and youth movements, the war between Israel and the Arab World, the decolonization of African countries, a time of great expectations and dreams. At VGIK there were 17 students in my class. We met with Arab and African students from different countries. It was a new experience for me. We had the opportunity to discuss all the issues concerning cinema, screenings, and our dreams of making films.

Talking About Trees (2019)

LK: Ibrahim, how did you come to choose your university, and how was your experience there?

IBRAHIM SHADDAD: I left Sudan on a scholarship from the DAAD to study agriculture at the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart. Before leaving Sudan I wanted to be a lawyer. I thought lawyers defend the people. Then I said: “Why not agriculture?” The problem of Sudan is agriculture. This would be very beneficial, but I realized that agriculture is very much bound by economics. So I went to the Freie Universität in Berlin to study economics. I realized that economics is not the boss. There is something called political science. So I joined this faculty. Then I realized that they are all good, but this is not my inner wish. They don’t talk to the people. I thought: “Art is agriculture, art is everything, life is art. So why not study art?” I used to love cinema when I was in Sudan, but I never imagined that I would study cinema. While in Berlin, I found out that there was a film university in the East [the German Academy of Film Art]. Even though I was in West Berlin I managed somehow to send them my application. They have an examination before entering the school. First they asked me to write a critique of an East German film. Then they asked me to come to the exam. I sat in a room full of German students. A teacher came with a piccolo and played a tune. Someone else said: “Write the tune you heard.” Mamma mia. I’d never heard a tune like this. The German students were scribbling on their music sheets and I didn’t write anything. Then the next exam was about drawing. I thought I can draw, but all the other students were like Rembrandt. When they accepted me I wondered why? Did they accept me because everything this Black guy will learn will be beneficial to his country? Ten were accepted, only two were foreigners, and the rest Germans. My time at the school was the most lovely time I’ve spent in all my life. It’s very strange. When people asked me about my nationality I used to say German because I really felt like a German, a Black German. I was very much involved in German society, I spent all my time with the German people.

EM: I’ve loved cinema since I was in high school. In the late 1960s there was a Sudanese Cinema Club, where I used to attend the screenings. After high school, I decided to study cinema in Egypt since it was close to Sudan and the tuition was affordable. So I applied to the Higher Institute of Cinema in Cairo, knowing also that Cairo is a big city, and one can encounter and learn about different cinema schools from all over the world. There were several cultural centers that screened films, and there was also the Egyptian Film Critics Association. I got accepted and started learning more about cinema, not only from the institute, but also from the screenings and readings. In my graduation project I thought about going to Sudan, but there was no cinema industry in Sudan as such, so I wanted to use this opportunity and make a film based on a Sudanese story in Cairo. I managed to do this in Al Dhareeh (The Tomb). After graduation I came back and worked in the Film Production Administration, and two years later I was moved to the Cinema Section of the Department of Culture, where I met Ibrahim and Suliman, and we became friends until today.

LK: Then you left Sudan again. How long did you stay away?

EM: After the RCC (Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation) coup d’état in 1989, I traveled to Jeddah and worked in the ART TV Station [Arab Radio and Television Network] from 1996 until 2004. This was an opportunity to learn about TV production and its technologies. But I used to come to Sudan to meet Suliman, Manar, and the other colleagues. Ibrahim was in Cairo and then left for Canada, so we used to write to each other and sometimes talk on the phone.

LK: Ibrahim, how did you experience this time, and how were you in touch with the others?

IS: Suliman and I were dismissed from the State Corporation for Cinema. Then we were interrogated and detained by the secret service. It was a reason to leave Sudan because at that time it was very difficult for everybody. The nearest place was Cairo. I stayed there for five, six years. Then I went as a refugee to Canada where I stayed around 15 years. I got Canadian nationality. In Egypt I started to work on two films. One of them was a short film about the old Sudanese generation who lived in Egypt. The other film was a long feature based on an Egyptian story. But I didn’t get the money to do it. After leaving Cairo, I worked most of the time in the theater in Canada. I also did workshops on videomaking beginning in the 2000s, and made a short film about the Canadian oil drilling companies working in Sudan. I also wrote a play which was staged in a Canadian theater. I went back to Sudan because of my mother. I didn’t want to at first, but I came. I came here and I got stuck, since my friends are here.

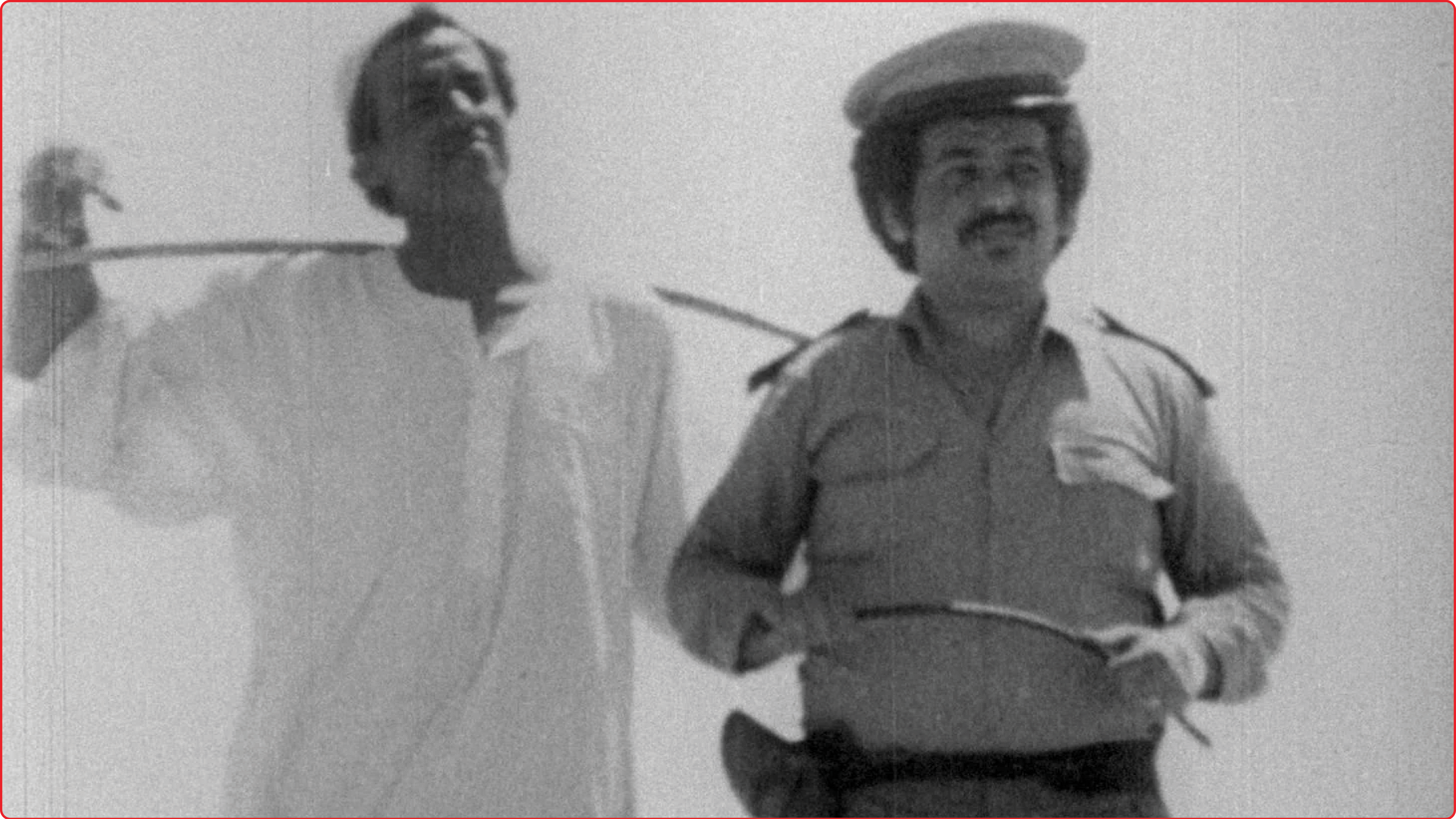

Al Dhareeh (The Tomb, 1977)

LK: So even while you were in different places you always kept in touch?

SE: At the time when Eltayeb and Ibrahim left, those who stayed in Sudan and all our friends from the Sudanese Film Group and Film Club, we used to meet the first Saturday each month to keep our relations alive. Sometimes we screened films on VHS and discussed them. We also read together the letters of Eltayeb and Ibrahim and wrote back.

LK: In 1989, after establishing the SFG, there was a coup. The political situation changed in the midst of establishing this organization. How did that influence your work?

SE: Actually, SFG was established in April 1989, and less than two months later the coup d’état happened. All civil society organizations were banned and everyone was seeking to get far away from the toughness of the regime.

LK: So you couldn’t work very much. Then in 2005 you re-registered SFG? What activities did you then start?

SE: After the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 [aka Naivasha Agreement] and the preparations for the elections that took place in 2010, the European Union Delegation announced a call for proposals. During this time the Sudanese Environment Conservation Society intended to produce films about the crisis in Darfur in partnership with the SFG. We wrote a proposal titled “Windows of Hope: Films for the Future.” With the grant we were able to equip our office with all the necessary equipment and conducted workshops. Three films were produced about the conflict in Darfur in the three major states: Nahny wa aldemokratia (We and Democracy), Altahaoul (The Transformation), Allianz (The Treasure).

LK: So you actually started producing some films?

SE: Yes, and before this there was a sort of partnership with the Sudanese Environment Conservation Society during the 1990s. We made two films for them: one by Eltayeb [Tale of Almatorat, 1995] and one I did [The Last Haven, 1996].

LK: Another of SFG’s activities was a mobile cinema, and Ibrahim was its coordinator. Maybe you can tell a little bit more about it.

IS: It was a project destined to expound problems to certain communities. Different provinces in Sudan have different problems. We targeted the Kassala state, the North Kordofan state, Khartoum state, and Omdurman. We talked about each problem before and after the screening to see the impact of the film, arrive at solutions, and maybe exchange points of awareness between them. There was also the storytelling program where they would tell stories about their own experiences, for example of circumcision. The problems were diverse. We did workshops on camera, sound, directing, and screenwriting. Then we provided cameras, computers, internet, and equipped them so as to document their own stories and be part of the continuous shows. We did this for around two years.

LK: Now you organize the Film Club. In the documentary about the SFG, Talking About Trees (2019), you want to reopen a cinema, and we see a screening of Modern Times (1936)…

IS: The Modern Times screening was actually not meant for an audience. That was one of the trials. We were testing the projector and the sound. When the film started, the people around the area had heard the music and came. Practically the whole cinema was occupied.

LK: So people are hungry for cinema.

IS: Yes. The screening at the Revolution Cinema which we prepare in Talking About Trees was based on a questionnaire which we did in the neighborhood. The choice was Django Unchained (2012).

LK: What happened to the Revolution Cinema and your efforts to reopen it?

EM: The Revolution Cinema is one of the cinema theaters that have been closed for decades, and we did everything we could to make this screening happen. We got the approval of the person in charge of the cinema, got in touch with the neighbors in the area, did publicity, did some maintenance work in the theater, cleaned the screen, fixed the seats, did a screening test, and designed a survey for the audience. In the end the authorities didn’t give us the permission.

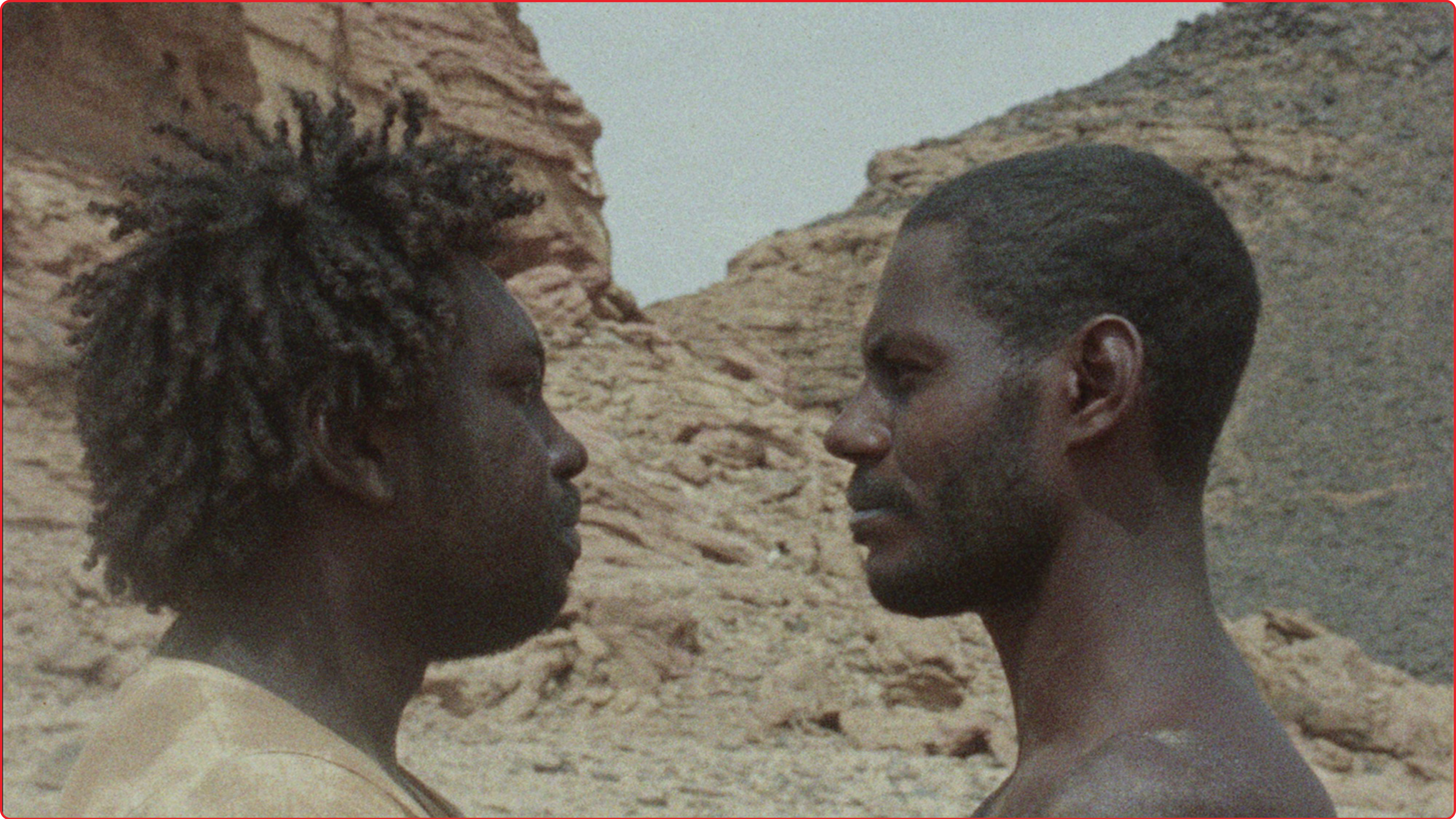

Jamal (A Camel, 1981)

LK: 2019 is a new situation for Sudan. How does this influence SFG? What kind of ideas do you have? What role do you see for filmmaking, for yourselves, for SFG in the months and years to come?

IS: One of our priorities now is to reopen the cinemas. Either the old cinemas or try to find interested people with some money to build new cinemas. We are demanding of the government to make a public declaration that cinema is important to the society, and that they are going to do their best to ease all the obstacles for cinema-making and cinema viewing.

LK: What is the role of cinema?

IS: Its role is to make the people understand that we are in a new era and we need to change. We need to accept what’s going on in order to understand it and to change. We are entering sort of a modernism, a time not lived before in Sudan. We are actually very backward. We are living a useless history.

LK: A large number of people in this country are under 30, and they have not experienced what you have. How do you feel about them as driving this change, and what do you think about them also making films?

IS: These are two separate things. It is normal in every country that the generations may differ in general attitude, politics, or culture, but I wonder about the extent of the political awareness and understanding of the whole situation. Is it a revolution like going to the streets and shouting, or is there something behind it like experience or study. They want to see very quick changes which is not going to happen. I feel filmmaking is one of the most important things now with other art media to help the people to see life in a different light, to understand that we have to change. [Ed: Since the beginning of the revolution, the Sudanese Film Group has been collecting footage to create a library of the revolution so that people can make use of it.] Coming to your next point. The younger generation knows very well how to take photos, how to shoot, how to edit and so on. But filmmaking is something else.

EM: What happened in Sudan was because of the courage of the youth, and at the beginning it was an isolated revolution, in the sense that there was not any media attention to it. The attention eventually happened because of the image. The videos and images on social media, and their sheer amount, forced the media outlets to pay attention to what is going on in Sudan.

SE: The media relied on all those videos that came out, even though they were not of the highest quality according to the professional standards. All this was the work of the youth. But as Ibrahim said, just shooting something does not make it a film, and there has been talk after this technological revolution that people perhaps need to redefine what a documentary film is. There is a huge amount of videos on social media, but these are not films. But since then you see the desire and the passion to make films. But we have to differentiate: is it just a hobby?

LK: Is this a discussion that can happen, now that you can help as SFG …

IS: This is actually what is going to happen next.

SE: This desire has to be organized. There should be workshops, like the trainings you did before. After that, the important question is: is it my profession?

LK: Shukran.

This interview was conducted at the office of the Sudanese Film Group on August 21, 2019. It was first published in the Booklet accompanying the Arsenal DVD release of the Sudanese Film Group in 2020.

Lilli Kobler was the director of the Goethe-Institut Sudan in Khartoum from 2018-2022.

Al Habil (A Rope, 1985)