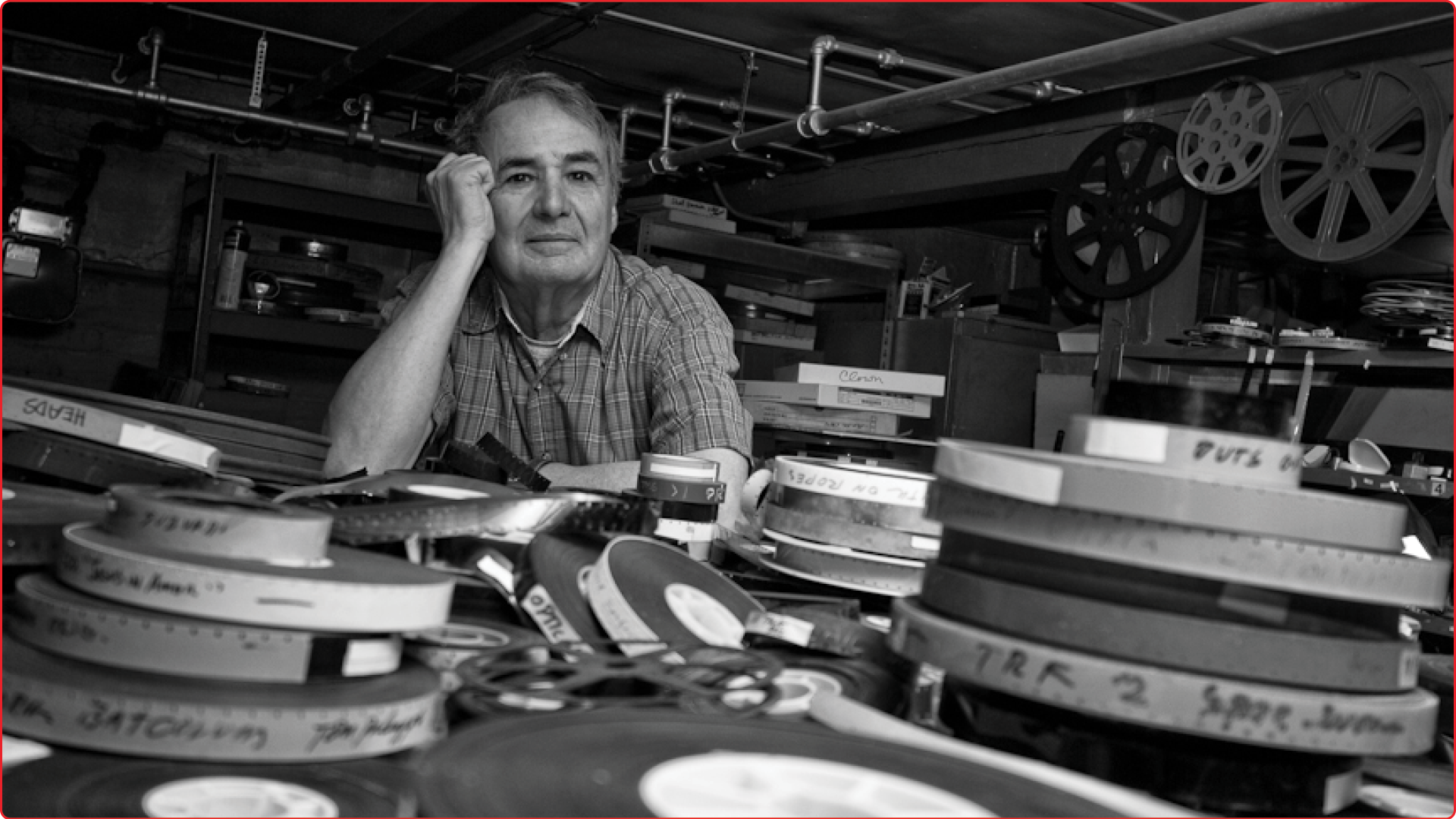

Tom Palazzolo

BY

Chris Boeckmann

Underground filmmaker Tom Palazzolo, aka Tommy Chicago, discusses his idiosyncratic films and career.

Tom Palazzolo’s America opens Saturday, July 8.

Every city should be so lucky as to have a filmmaker like Tom Palazzolo chronicling its existence. From rowdy street protests to colorful pet parades, awkward prom nights to even more awkward wedding showers, Palazzolo has documented Chicago life in more than 50 vibrant films since the late 1960s. His subjects vary widely, but his warmth and humor are constants. Early champion and friend Roger Ebert, who dubbed him “Chicago’s filmmaker laureate,” wrote that you can feel his movies “smile about human nature.”

After studying at the circus-affiliated Ringling College of Art and Design in Sarasota, Florida, Palazzolo moved to Chicago in 1960 with aspirations of becoming a painter. One of his professors at the Art Institute of Chicago, Kenneth Josephson, turned him onto photography and film. Palazzolo would borrow Josephson’s library card to watch surrealist classics, as well as films from the Free Cinema movement in Britain, which championed handmade, unsentimental depictions of reality. Often made in response to the heated political climate, Palazzolo’s early documentaries pair his striking street photography with brilliant non-diegetic soundtracks: sometimes a puckish mix of pop songs, other times eerie musique concrète compositions. Heralded by critics, these experimental shorts, including America’s in Real Trouble (1967) and The Pigeon Lady (1966), became fixtures on the film society circuit.

Palazzolo’s career took a turn in the early 1970s when he met Jeff Kreines, a self-taught teenage filmmaking prodigy who helped him transition to sync sound documentaries and towards cinéma vérité, the approach that has come to constitute the majority of his oeuvre.

I sat down with Palazzolo, who is also known as Tommy Chicago, in his Oak Park home, where he resides with his wife Marcia, who is also an artist, and their dog Oliver.—Chris Boeckmann

CHRIS BOECKMANN: Did you come up with the moniker Tommy Chicago?

TOM PALAZZOLO: I adopted that name. On Hubbard Street, where I lived, there was a little resale store, and they had photos of vaudeville stars. The photographer signed them “Maurice of Chicago.” So I adopted that because my films are all about Chicago—except for Lilly’s World of Wax (1986).

CB: Oh right, about Lillie Santangelo and her World of Wax Musée closing down. That one is set at Coney Island. It’s such a beautiful work of portraiture.

TP: I like outsider people. And the poor thing, all she had were these wax figures of people from way back in the 1920s and 1930s, Joe Lewis and all that. The younger crowd had no idea who these people were, so she would approach people like Michael Jackson and say, “Can I do a wax figurine?” They’d say, “Sure, for $50,000.” She couldn’t do it, poor thing. Also, I made a mistake and misspelled her name in the film’s title.

CB: Watching today, there’s obviously a time capsule element to your work; many of these Chicago spaces and traditions you’re encountering no longer exist. Lilly’s World is one of the only films where you’re filming something that’s already in the process of disappearing. Were you thinking about that much back then?

TP: No, I thought they’d be there forever, I really did. There’s Maxwell Street [At Maxwell Street, 1984]. I just assumed it would always be there. And Riverview [Park] too [in The Tattooed Lady of Riverview, 1967]. That’s gone, long gone. No, I’m never thinking more than a week ahead.

CB: I’m guessing that means there’s not a ton of planning involved in your movies?

TP: I like to improvise. I like to discover things. In my case, anything I plan never works out. It has to be spontaneous. I just have to go and hope that something will happen. Most of the time it does. We get something. These films are adventures for me. Going out and connecting with people. For some reason I’m not intimidating at all, people accept me.

Love It/Leave It (1973)

CB: You never have to convince people to be in your movies?

TP: No. I think people like the attention. One woman said to me, “You know, a lot of people are making these films, and they say they’ll put them on television, but they never are.” But mine were on TV. The major television stations wouldn’t go near any of my documentaries. They’d send me letters: “Oh, thank you for submitting to PBS’s something or other.” We never made it there, but I had a lot of shows on the local public television station, WTTW. They showed a lot of my short films, and they paid.

CB: I wanted to ask about this house. It’s a charming home; I feel like I could spend hours here looking at all your art. How did you land in Oak Park?

TP: The house is over 100 years old. We’ve lived here since 1972. It was very inexpensive then. We paid $37,000. Now it’s probably worth half a million.

CB: What was that decision-making process?

TP: I had a loft in a very iffy place on Hubbard. And we had just had our first daughter, Sarah. Marcia said to me, “You know, there are no schools around here. We should move to Oak Park.” Because her parents lived right down the block, I thought, “Babysitters!” It turns out they got a Winnebago and were never home. My schemes don’t always work.

It’s completely different from the city, where all night I would hear trucks backfiring—poom!—and drunks yelling and throwing up outside. So yeah, it was time to move, but I liked that apartment. I’d look out my window. The very first film I made was The Pigeon Lady, which Roger Ebert liked. I first saw her out my window on Hubbard, and I ran out and followed her.

Marcia and I got married in December of 1968. But then—this would have been the beginning of 1969—the US Information Service wanted to show experimental films in the Middle East so people there could see how much democracy and freedom we had in America, because we made all these nutty films. One of them was Brakhage’s Dog Star Man (1961-64). So they sent me over to the Middle East, and sneakily—because I’m always looking for something underhanded—I said, “Marcia, why don’t you meet me there in Beirut? This will be our honeymoon and I won’t have to pay anything.”

CB: How were you chosen for that program?

TP: They decided to use me for the tour rather than the hot rod New York and LA filmmakers because they thought they would be political and say anti-Vietnam War things. They didn’t know that I was also opposed to the War. I didn’t want to go to Vietnam. Luckily I got out because I was in school and they gave me an exemption. And also because I come from Missouri. I would go there, and they’d say, “Oh no, no, you don’t have to go, we have our quota. All the good ol’ boys in Missouri signed up to go there.” Good God, I hope they all made it back!

CB: How did that tour work out?

TP: It worked out pretty good. Sometimes it was a little scary. But everyone was nice, and we showed the films. They liked the films, except when I showed whatshisname who does the frames of just black and white.

CB: Tony Conrad?

TP: After about a minute of that, they started screaming, and I turned it off and never showed it again. Because it’s annoying! He said the soundtrack should be the sprockets: ah ah ah ah!

CB: Which of your films screened?

TP: They showed O (1967), because there was no problem with the language barrier. Everyone just had one film. We went to Israel, Jordan, India, Ceylon. I was the only filmmaker on the tour. They didn’t trust those liberals from the coasts. And they would brief me when I got there, very adamantly, “Don’t ever mention Vietnam.”

CB: I still can’t wrap my head around the government creating this tour.

TP: They were looking for someone, and they had a cozy relationship with Second City [theater company], who I was tight with. The woman there, Joyce Sloan, said, “You should use Tom.” Nothing ever works out when I speak for myself, but when someone else intervenes, it does. Again, the State Department didn’t know I was marching with [Dr. Martin Luther] King. And they weren’t aware of America’s in Real Trouble, which is not a pretty picture of the country. So I was lucky to get that opportunity.

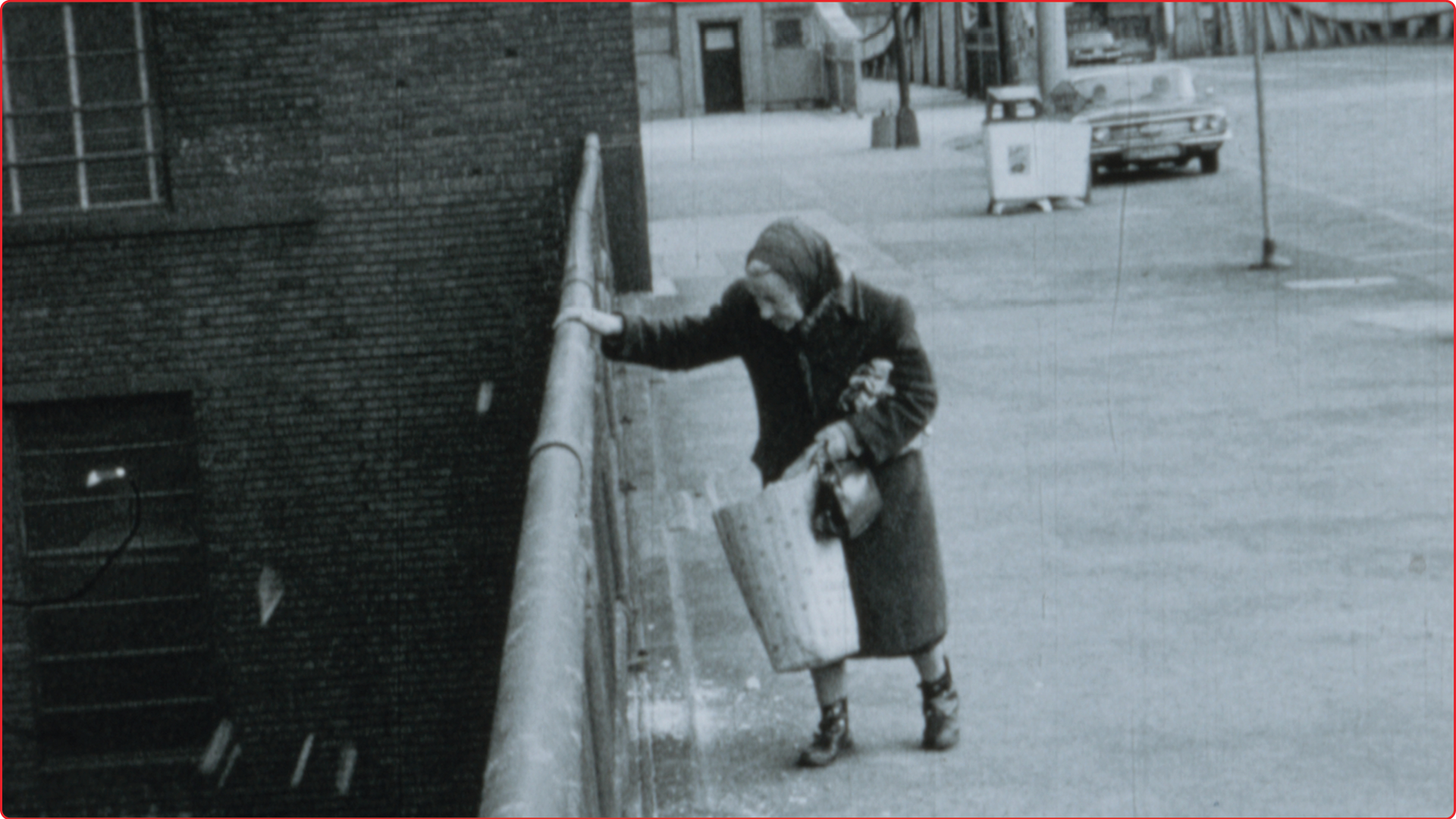

The Pigeon Lady (1966)

CB: How did you and Marcia meet?

TP: She went to the University of Illinois Chicago. I was at the Art Institute. To make a little money, I became—I’ll use my St. Louis accent here—they hired me as a gua-rrd. You’ve been to the Art Institute. You know there’s this garden where people eat near the statues? She was a waitress there. One day I went over to the window where the waitresses stood. She looked over at me, and I wrote a note: You have a nice smile. She immediately laughed. Later on, she took a photo class, and that’s where we really met.

CB: You collaborated?

TP: No. Marcia’s primarily a still photographer. She has a book coming out. We’ll get you one.

CB: Do you show each other your work while you’re making it?

MARCIA PALAZZOLO: He doesn’t. He’s very focused.

TP: Especially now that I have my cataracts.

CB: Can you tell me about Floating Cinematheque, the screening series you helped start in the mid-1960s?

TP: We pretended it was a secret location every time, But it was actually always in our apartment on Hubbard Street. We had a little 16mm projector. We would show my films and my friend who lived downstairs, John Heinz, would show his films also.

CB: The police were cracking down on screenings back then?

TP: This was before they got rid of censorship. They had a special board who were the wives of deceased aldermen. They would sit there like this [Tom gives a stern look], like they had to do a job. They would screen films and give them a special pass to be shown. So this minister at a Unitarian church had a film night, and I didn’t bother to get an okay from the screening board beforehand. This was for O. The police came in, confiscated the film, and arrested the minister. The case was dropped because there was no nudity or anything.

I did have another film they rejected called He (1966). But then they had an appeals court of Catholic lawyers, and so I came in and defended myself. I said, “I go to art school, nudity is not a real thing, I draw and paint nude people all the time.” They said, “Absolutely not, you’re banned for life.” But then the next year they got rid of censorship in the whole country.

CB: How did you come to film the police training session for Love It/Leave It (1973)?

TP: Oh. That was another underhanded thing I did. A friend of mine had an editing house. I saw that he was working on this film for the police. And this is footage that the police shot. I, being unscrupulous, had some of it copied and put it into my film thinking no one would ever know about my underground film… Sadly he did find out about it, our relationship was a little strained after that. In the arts, we have a special license to do whatever we damn please. Without that, there wouldn’t be people like Picasso and the surrealists. So yes, that footage is purloined.

CB: I saw that some of your films—including Love It/Leave It and Enjoy Yourself (1974)– played at the Flaherty Seminar in 1974. What was that experience like?

TP: It was interesting. Very critical. They didn’t share my sense of humor at all. New Yorkers, whoa, they’re hard to please! I didn’t want them to say, “Oh these are great films,” but they were dismissive.

CB: On what grounds?

TP: On any grounds they could think of. It was a negative experience. And I wasn’t the only one that they wanted to think badly of.

CB: Where have you been happiest with the reception to your films?

TP: I was very happy when the Whitney showed a bunch of my films in 1983. Oh, and early on in 1968, the Museum of Modern Art had a big show of my work. Mostly the crowd was very accepting. One guy got up after one of the shows and yelled out, “I know what you’re trying to do, but you’re failing at it!” and walked out.

Pets on Parade (1971)

CB: Two of the early portrait films Metrograph is screening, Pigeon Lady and The Tattooed Lady of Riverview, were made without sync sound. Most of your portraits are conversation-driven. It’s so interesting to go back and watch these films where you had to find a different cinematic language.

TP: Yeah, with the Tattooed Lady, I recorded her voiceover separately.

CB: Did you record an interview with the Pigeon Lady?

TP: No, she wasn’t terribly interested, and a little unhappy with me following her around, so it was mostly long shots of me following her. I experimented with slow motion and double exposures. I let that film run too long. I should have ended it. My influence early on was not documentary but films from the early 1920s: Un Chien Andalou (1929), and there’s one very funny one you might enjoy called Entr’acte (1924) by René Clair. Another big influence was Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958), which used news footage but in a collage way. I thought to myself, “Hell, there’s enough craziness going on in the street. I can do that and make a film where I don’t need news footage. I can use the craziness going on in Chicago instead.” I was making these artsy sort of films then, like O.

CB: I love O.

TP: That was typical of my Bolex days. Later, I knew I’d exhausted the Bolex. Plus I think it broke.

Then [the filmmaker] Jeff Kreines turned me on to these really interesting documentary people, like Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker. I knew I couldn’t keep making collage films forever, and I was interested in the documentary form. Jeff was ahead of me on that. He suggested I get one of these CP-16s that the cameramen at news stations used. It had magnetic sound on the edge, so I could be a one-man band. I didn’t need a sound man. All I needed was a microphone plugged into the camera.

Even then, I was always looking for a deal. I was looking to buy one. One of the agencies had one that had fallen behind a filing cabinet, but they didn’t know for a while, so they wrote it off on insurance. They sold it to me for a cheap price.

CB: I read a quote from Jeff where he said you were an expert at making films for cheap.

TP: I had a good relationship with the lab. All these cameramen would come in. They had 10-minute magazines. They would shoot only three minutes or something, and then sell me the remaining film for very cheap. I had a lot of sweetheart deals.

I loved Jeff’s early films, they were amazing. He was making films when he was 17 or something. We worked on the film Pets on Parade (1971). At that time, I thought anything that happens in the suburbs is going to be funny and kitschy. And he keeps saying all the time, “It shows the worst of both of us.” Well, I don’t think so. I was happy with it, I thought he did a good job! And I thought it was a funny film!

CB: You’ve said in other interviews that humor became less fashionable in the film world. Why do you think that is?

TP: I’ve always been interested in humor. I remember as a kid I would go to the library. I didn’t go there to read Ivanhoe, I went to the cartoon section. I don’t know where I got this silliness from.

CB: Were other filmmakers around you making funny movies?

TP: John Heinz might have made some funny little films there, but not really. Most of them were experimental. There’s a guy named Wayne Boyer, who really was an experimental filmmaker, and boy, he did interesting things. I can’t say that I was an experimental filmmaker—more like a collage filmmaker. Of course, the big catch phrase then was underground filmmakers. I was called an underground filmmaker, whoo! It made me sound exciting, sexy.

CB: You filmed a lot of nudity. Was that common among your filmmaking peers

TP: I was pretty much the only one. There’s a couple of reasons for me doing that. First of all, there were these midnight shows in other states. I knew if I had a little nudity they would rent it, and I’d make some money on it. Plus, it was sort of in the air in the 1960s. There was more openness.

Nudity is forbidden here in Illinois, so I mostly shot at this [nudist camp] called Naked City in Indiana. That place existed so that the guy could make money, because all these men with cameras would go hoping to get shots of naked women and men. You paid to get in. In my case, me and [the filmmaker] Mark Rance snuck in, we didn’t pay the $20. We found a way to go through the woods and get in. So there’s a funny film called Sneakin’ and Peekin’ (1976).

I like films that comment on society. I don’t want to be critical of it, I kind of like it that things are crazy in our culture. Nowadays they are a little too crazy with the rise of the right. I would never deal with that—although I did shoot the Nazis [for the Marquette Park films, 1976-1978].

CB: You mentioned earlier that you’re drawn to outsiders. Why is that?

TP: I grew up in St. Louis, right near the Public School stadium, where they would have a circus come to town every summer for a couple weeks. I would get in free by selling soda. And I’d get to see the clowns. I related to the clowns. Outsiders are the only people I really have any chance of connecting with. They’re the most giving. They’re easy to work with. They’re nice people. They and their lives are interesting to me. So if another outsider comes along, I’ll try and learn how to use that digital camera.

Chris Boeckmann is a documentary story consultant and programmer from Missouri. He is a co-writer of the upcoming feature Flying Lessons, directed by Elizabeth Nichols.

The Tattooed Lady of Riverview (1967)