No Cutting Edge But His Own

BY

Will Sloan

Revisiting James Cameron’s beleaguered first underwater dive, The Abyss (1989).

The Abyss: Special Edition opens at Metrograph on Friday, December 8 as part of Sub-Marine Mysteries (and Wonders).

During the 2009 Oscar campaign, James Cameron and Quentin Tarantino took part in a roundtable discussion during which the latter pledged to retire from filmmaking when he turned 60. Tarantino, 46 at the time, has often likened filmmakers to athletes who lose their prowess as they age, telling the Hollywood Reporter, “I don’t want that bad, out-of-touch comedy in my filmography, the movie that makes people think, ‘Oh man, he still thinks it’s 20 years ago.’” Most of the panel—including Kathryn Bigelow, Peter Jackson, Jason Reitman, and Lee Daniels—just laughed at his pronouncement, but James Cameron, age 55, was the only one with a rejoinder: “I took my hiatus already, because I figured I can still be directing when I’m 80, but I can’t be doing the deep-ocean expedition stuff.”

The two men were and are among the few living directors whose names are major box-office draws, but their relationships with the zeitgeist are not the same. Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) pulled off the neat trick of helping define “cool” for its decade. Nobody stays at the bleeding edge forever, and his recent Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) is an unabashed lament for old ways and lost futures. This evolution can be seen as evidence of maturation in Tarantino, or at least of ageing, but he might fear it as a sign of losing his grip on the zeitgeist. The zeitgeist can’t be controlled, only observed and reacted to; art is fickle and follows no linear arc of progress; but technology—the realm of Cameron’s mastery—is another matter. Cameron’s newly restored The Abyss: Special Edition offers an opportunity to consider the nature of Cameron’s talents. It was first released in 1989, but seen today, feels like it could have easily been completed a week before or after Cameron’s recent Avatar: The Way of Water (2022). Its particular technical achievements are unsurpassed and maybe unsurpassable. Its story, characters, and ideas are elemental.

The Abyss (1989)

On the rare occasions when Cameron releases a movie, he tends to introduce or popularize technologies that become industry standard, from the perfection of CGI morphing effects for Terminator 2 (1991) to the (temporary) popularity of 3D and (permanent) migration to digital projection after Avatar (2009). In 1989, The Abyss was notable for the unprecedented scale of its underwater shooting—an experiment that led to it gaining a reputation as one of the most difficult and troubled Hollywood productions of all time. Cameron set a high bar for himself, saying, “If I couldn’t do what 2001: A Space Odyssey did for science-fiction films taking place in space … in the underwater arena, then I didn’t want to make the movie.”

The production headaches are chronicled in Under Pressure: Making ‘The Abyss’ (1993), an hour-long making-of documentary that really ought to be watched in conjunction with its subject, as Burden of Dreams often is with Fitzcarraldo (both 1982). The plot follows the crew of an oil rig (including Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as an estranged couple) as they investigate the wreckage of a nuclear submarine at the bottom of the ocean, and stumble onto a mysterious presence from another world. Most of the action takes place underwater—a shooting challenge that, for Cameron, represented the project’s raison d’être. The bulk of the six-month shoot took place in an abandoned nuclear project outside Gaffney, South Carolina, whose two massive tanks supported millions of gallons of water. Underwater shooting required new infrastructure for heating, filtration, and clarity, and submergible sets that could endure the pressure. Technical catastrophes, from ruptured tanks to faulty piping, led to long shooting delays. The stillness of the water created a mirror effect on the surface, requiring thousands of black plastic beads to blot out light (a black tarp would have posed too great a safety risk if someone needed to swim up for air).

All this was before actual human beings entered the equation. The enormous amount of chlorine used to reduce mist led to burned skin and bleached hair. Respirator noises obscured the dialogue, and had to be scrubbed in post-production. Two-way communication was impossible: when Cameron was submerged, he spoke through an underwater P.A. system, but the actors could only communicate via hand gestures in lip-reading. Safety divers were hired to shadow the cast, but when Harris needed oxygen after performing a stunt without his helmet, his diver was tangled near the surface; had a quick-witted cameraman not swam over in time, there could have been tragedy (Cameron, for his part, also almost drowned). Beyond that, how would you like to sit in dirty water for six straight months? Let’s not even speculate on the bathroom situation.

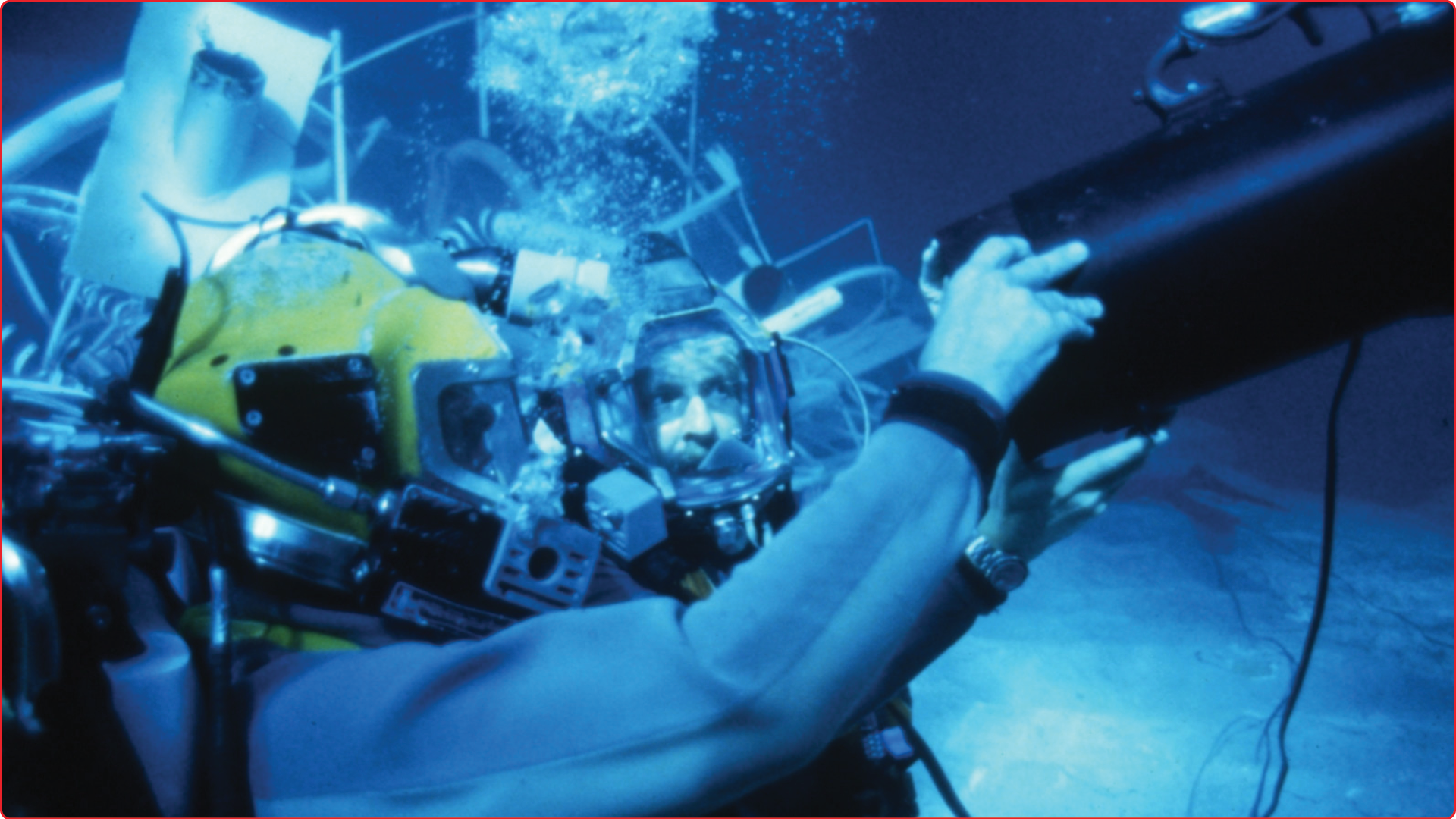

James Cameron on the underwater set of The Abyss (1989).

In one of the movie’s most famous scenes, a rat is placed in a container filled with oxygenated fluorocarbon fluid—a real, breathable liquid, which has never been tested on humans. The scene is deeply suspenseful, but the animal’s fear is so obviously real that I don’t enjoy watching it. Knowing that both Harris and Mastrantonio (who fled one gruelling day’s shoot yelling “We are not animals!”) refused to talk about The Abyss for years gives the rest of the film a similar edge. Let’s take it as given that no movie is worth this kind of risk and suffering. Now let’s flippantly put that aside and ask: was The Abyss “worth it”? In my opinion, the answer is no. Still, it’s well worth seeing or re-seeing. It has visual beauty, impressive stunts, and the story works well enough, and Lord knows Cameron can build a set piece.

Cameron’s screenwriting—certainly the most commonly derided of his talents—is that of a qualified craftsman who uses good building blocks to lay a reliable foundation. He has populist instincts: he likes star-crossed lovers or exes with an undercurrent of chemistry; poor heroes and rich villains. He is capable of narrative ingenuity, like in the second half of Titanic (1997) with its cross-cutting between the intimate story of Jack and Rose, and the obsessive, minute-by-minute cataloguing of the ship’s destruction. (At what time would the engine room have fully submerged? When did the dishes in the dining room start falling off the tables?) He builds his spectacular action scenes around ideas with a proven record of success.

In Under Pressure, Cameron observes, “The whole film seems to build to that moment where it’s just two people in a tin can and one of them is going to die.” How many times since has he returned to the ticking-clock suspense of two people locked in a sinking ship? It works every time. He relies on clichés and archetypes because he believes in them, and is able to imbue them with feeling. He states his ideas in his dialogue, and there is never much subtext to tease out. “I like to make films for the mainstream, for the global audience,” he said in that Oscar roundtable. “I’m not interested in making a film for the film festival crowds. I’d just as soon not meet people and not talk about the movie. And I don’t mean that in some kind of disdainful way, it’s just the movie should be the movie.”

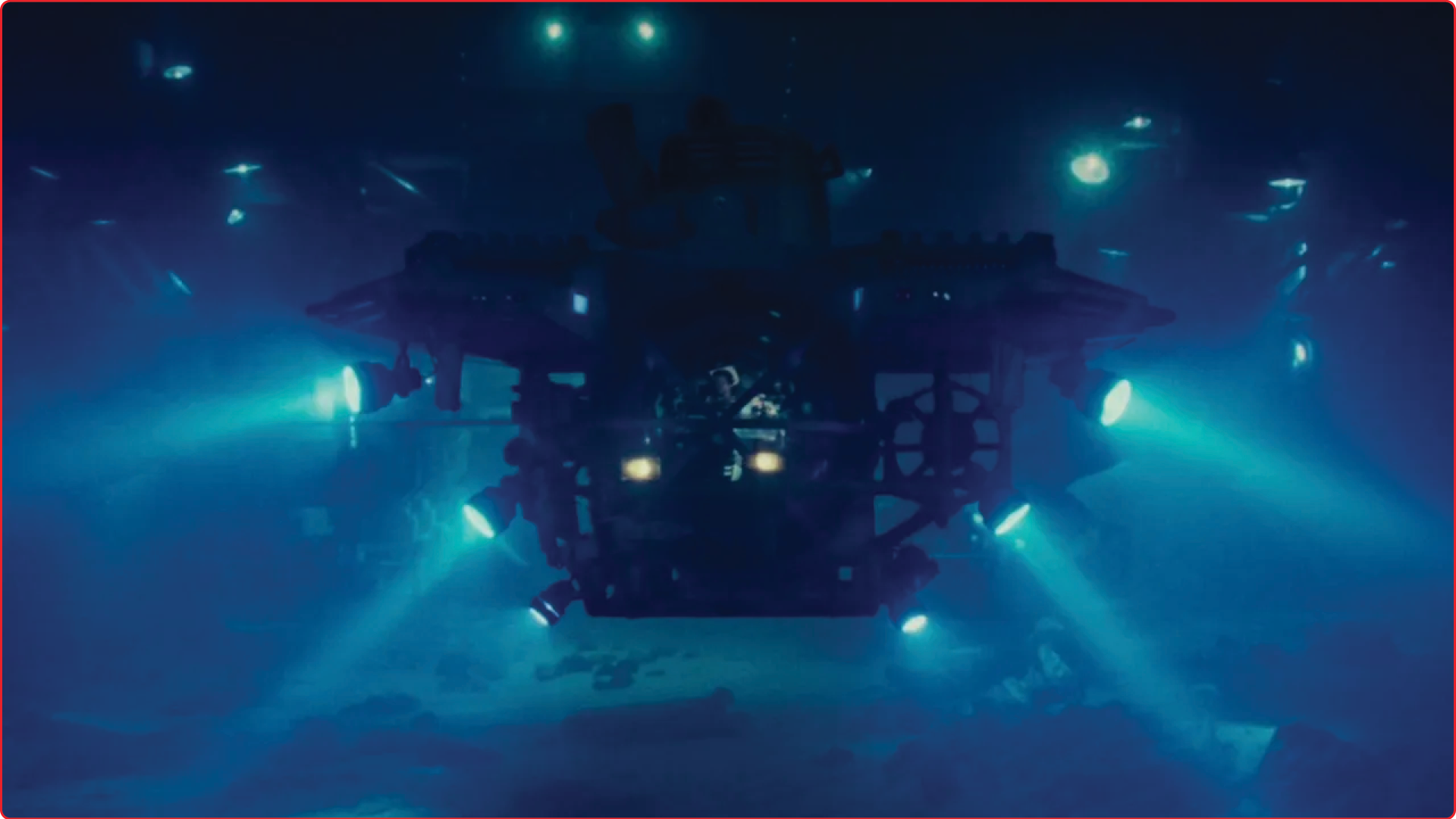

The Abyss (1989)

When Avatar: The Way of Water was released to beleaguered post-lockdown multiplexes, there was a sense that it represented a contrast to its fellow Disney stablemates in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Like virtually all working directors who have had a press cycle in the last decade, Cameron has been asked about the Marvel, and has more or less communicated that those movies are less substantial than his Avatars. He’s right. Compare the numbing, weightless CGI spectacle of so many modern blockbusters, churned out by underpaid VFX artists in digital sweatshops, to the results of Cameron’s meticulous approach. Compare Marvel’s strategically muddled politics and “So that just happened…” sense of humor to the Avatars, which are earnest, serious, full of awe for the natural world, and about as bluntly anti-imperial as a megabucks Disney blockbuster is allowed to be. Compare the glib Teflon Avengers with Cameron’s characters, who suffer, bleed, die, kill, and mourn.

If I have a reservation about Cameron’s brand of directorial megalomania beyond the obvious, it is this: when Werner Herzog corrals an army of Peruvians to pull a steamship over a mountain in Fitzcarraldo, he creates an image that had never been seen before; but halfway through Avatar: The Way of Water, I realized that even the most beautifully rendered and photorealistic CGI image of a sunset is less beautiful to me than an actual sunset.

Moreover, if his goal for The Abyss was really to create an underwater 2001, then on those terms he failed. The greatness of Kubrick’s movie stretches beyond its technical innovations into its quiet, its mystery, and its lack of comforting platitudes—in other words, the sorts of poetic ambiguities that Cameron distrusts. Still, The Abyss exists outside of time, and Cameron passes the Serious Artist test: the only cutting edge he respects is the one he carves for himself.

Will Sloan is a Toronto-based writer and podcast mogul. You can follow his adventures at willsloan.ca.

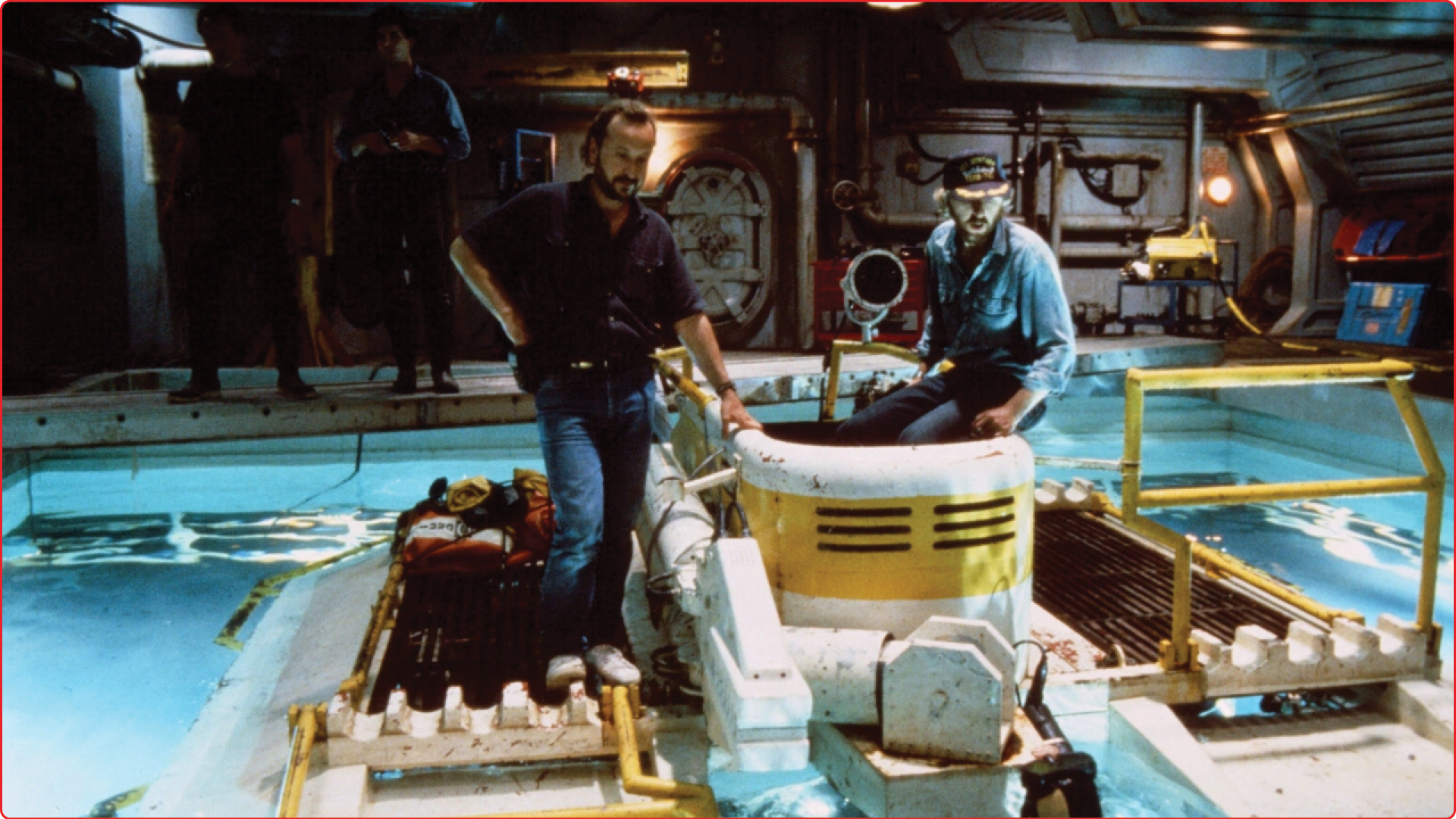

James Cameron on the set of The Abyss (1989).