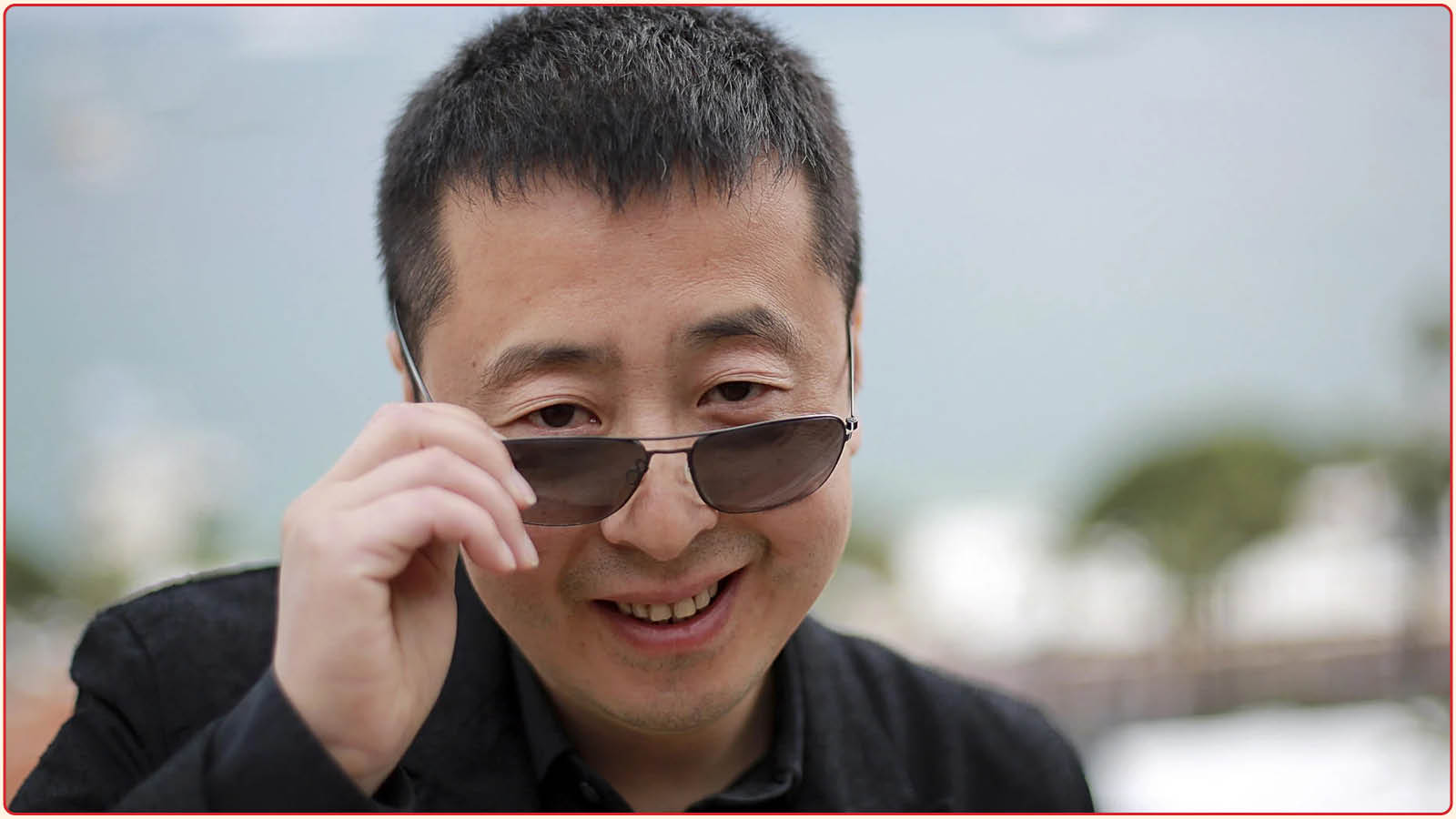

Jia Zhangke: “I’ve discovered myself in the last 20 years”

BY

Kelli Weston

Checking in with the lyrical filmmaker at the Cannes Film Festival premiere of his latest feature, Caught by the Tides.

Mountains May Depart and A Touch of Sin are currently streaming on Metrograph At Home as part of Cannes At Home. Ash is Purest White opens at 7 Ludlow on Friday, June 28 as part of Visionary Auteurs: Five Decades of mk2.

Eleven years ago, Jia Zhangke won the Cannes Film Festival’s top screenplay prize for his much acclaimed anthology thriller A Touch of Sin (2013). He had already established himself as a master portraitist of contemporary, post-socialist China, tracing its many upheavals and transformations across his then-nearly 25-year-long career. Jia returns to the Croisette this year—his sixth in competition—with another ambitious, soulful epic, Caught by the Tides (2024), starring his wife and frequent collaborator Zhao Tao as a woman searching for her lover after he disappears. Often hailed for his neo-realist propensities, Jia’s films—sprawling, expressive ventures into the murky depths of intimacy and betrayal—equally announce his affinity for impressionism. His slow-moving pans, lilting pace, and haunting imagery conspire to transport audiences to the liminal world his characters so often emotionally inhabit.

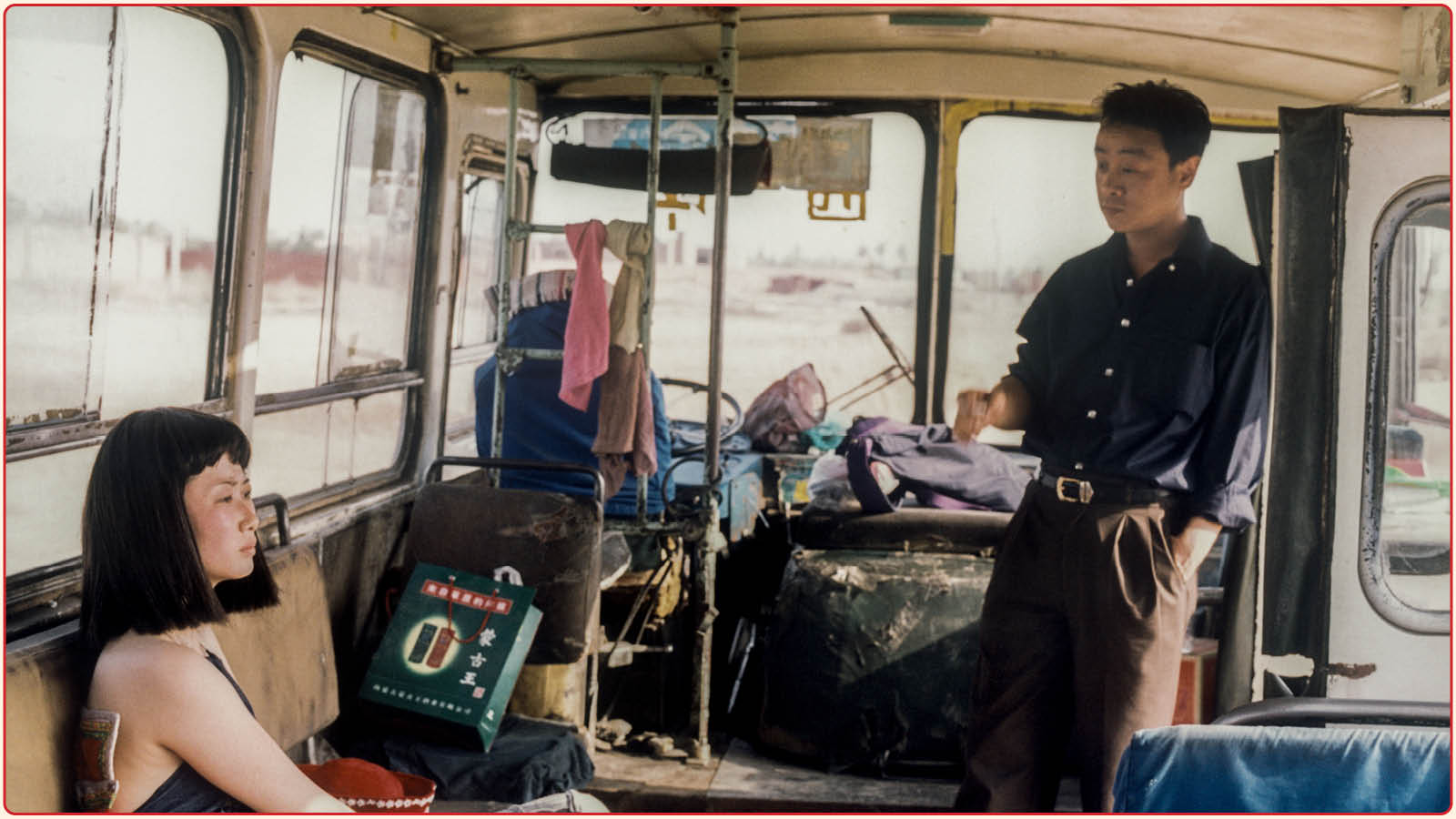

Like its immediate predecessors, love triangle melodrama Mountains May Depart (2015) and heartsick gangster’s moll tale Ash is Purest White (2018), Jia’s latest feature doubles as an unhappy love story and evocative ballad to his homeland. In fact, much of Caught by the Tides is composed of improvisational footage Jia has been shooting across China since 2001, and contains cut scenes from both Unknown Pleasures (2002) and Still Life (2006). Music has always been integral to his films, but Caught By the Tides could perhaps pass as a musical, its soundtrack brimming with traditional, popular, and alternative Chinese music. Zhao’s character, naturally, is the object of the film’s central orbit, the camera’s gaze scarcely able to conceal its enchantment. And indeed, the actress, with sparse dialogue, delivers one of her most commanding performances yet, a refined sketch of a woman mired in longing, after being separated from her manager, played by Jia favorite Zhubin Li. At Cannes, I spoke with the director about his new film, the stylistic and thematic echoes across his work, and how his working partnership with Zhao has evolved over the years. —Kelli Weston

Caught by the Tides (2024)

KELLI WESTON: Mountains May Depart, Ash is Purest White, and now Caught By the Tides seem to form a sort of unofficial trilogy where your characters embark on epic odysseys. When sculpting this latest portrait, did you already have the shape of the film you wanted to compose in mind or did you allow the footage to guide you?

JIA ZHANGKE: I had a few shapes in mind. Because, yes, indeed, I have made two films back-to-back with similarly large time spans. Some people, including my creative team, also asked: why are we making yet another film like this? I also had thought that maybe I should make a slice-of-life [film], just for a change. But Covid happened, and that put everything on pause.

I was very concerned about the social situation in contemporary China. It just so happened that I have been collecting footage and materials since 2001 with a project that had the running title A Man with a Digital Camera, paying homage to Dziga Vertov, and also [linking] 2001 with the infant stage of the DV filmmaking. As a habit, I use DV cameras to capture images wherever I go. I had thought that this might be a project that I would do until I retired, and I could then look back on the materials and maybe put on some kind of retrospective. Butas I said, Covid happened, and so I thought: this is the time. Rather than [wait for] retirement, this is the time for me to look back on this footage and images I have gathered: instead of a micro slice of life of contemporary China, I am looking at a slice of human history.

I decided to really think about how to tell this story, using—as you put it—this idea of an odyssey, the emotional journeys that these two characters have been through, by combining not only the old footage that I had but also the newly written script for the last third of the film.

Mountains May Depart (2015)

KW: I’m so curious about what that experience was like, emotionally or professionally, re-encountering this footage after such a long period of time? How had your perspective shifted?

JZ: Three main things stood out to me. First, revisiting this footage felt like revisiting the past. Because I had been filming for so long, I had forgotten what I had filmed. It was a shift in my personal memory. It took me back to 20 years, 10 years, eight years ago when I shot these people, the way they dress, the way they act, the environment, the sounds—they’re all so different from what I’m used to now. It was almost as if I was taking a time machine and traveled back to that particular moment when I captured those images. It was like a tunnel. It was like standing in a higher dimension, [looking down] to see the slow [march of] life of human beings.

The second thing that impressed me was that I realized how perfect it is for me to use DV as a device, as a vehicle to capture these images, especially when society is going through major transformations and people are so idealistic about the hopeful futures to come. At the time, as a filmmaker, the way I was using the DV technology was not very mature. It was almost like being in the infant stage, getting used to the technology. At the same time, that sense of uncertainty matches perfectly with this idea of a chaotic yet energetic society that I am trying to capture. It’s a surprisingly perfect marriage, using this particular device and technology to capture the energies of the era.

The third point: I’ve discovered myself in the last 20 years. I suddenly realized that who I am as a filmmaker has also evolved through the way that I move my camera, the rhythm of the shots, and also, the gaze. That really impressed upon me that I am indeed a different filmmaker now.

KW: Whenever I watch your films, I feel transported to a dreamlike state. There is such effortless poetry to your filmmaking that it often veils the precision of your craft. Could you talk a little about how you begin to map the structure of your films?

JZ: In terms of the structure [of Caught by the Tides], because the image we’re facing is complicated, there are multiple directions one can take It was also a conscious decision early on to start with the collective portrait and then narrow in on the female protagonist played by Zhao Tao. It’s almost as if with all the footage and the materials I have gathered, you see the context, the historical subtext of what this particular female character has experienced growing up in that particular era, within that particular social, political, and economic environment. That then informed the emotional and personal journeys that this character would take, along with the audience, later on. The old footage definitely captures the sights and sounds of the past era—it's almost impressionistic. But at the same time, I did not think that it was enough.

Caught by the Tides (2024)

KW: I know this film also contains scenes from Unknown Pleasures, which I believe was the first film that you and Zhao Tao collaborated on. How has your dynamic evolved over the years? How do you approach the development of her characters together?

JZ: On one hand, because we’ve worked together for so many years, I can feel the change in Zhao Tao. I think she’s become more and more powerful. In the same way that I have evolved as a filmmaker, she has evolved as an actor as well. This idea of the female sensibilities and female consciousness that she brought to this film definitely makes the film—and all the films that we have made—even better.

On the other hand, in terms of specifics, after working with her on a couple of films, I realized that her strengths are on set. She is not a very theoretical actress, she’s a very emotional actress. A very dynamic actress. She definitely shines on location. She’s someone who really knows how to make her presence felt in whatever space or situation she is in.

In the past, I would give very detailed directions but now, I just tell her why she is here, what the scene is trying to accomplish. All the rest, I let her decide on the spot how she thinks she can make a particular scene work and come alive.

I can pinpoint one particular scene: at the end [of Caught by the Tides], in my imagination of this character without saying anything—not to suggest that she has nothing to say, it’s just she decides not to speak for almost the entire film—and then, when doing one of the many takes, she somehow decided to make that big scream. That was unexpected. I thought that she was just going to run, and then that would be the end of the film. That particular scream really empowered her character more than I could have ever expected. So again, that is something that I just need to give her: that kind of environment, that creative license, and that freedom to react in real time, spontaneously, on set. And that is how we are collaborating now more than ever before.

This interview has been translated by Vincent (Tzu-Wen) Cheng.

Kelli Weston is an editor at Metrograph.

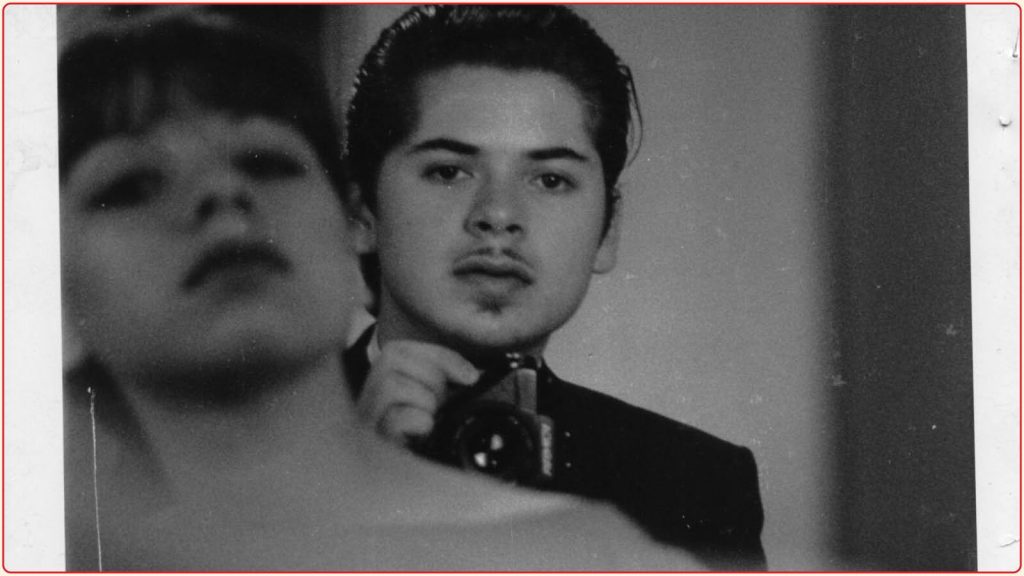

A Touch of Sin (2013)