Essay

Jean-Pierre Léaud’s Finest Follies

A close-up on six of Jean-Pierre Léaud’s finest comic performances.

Share:

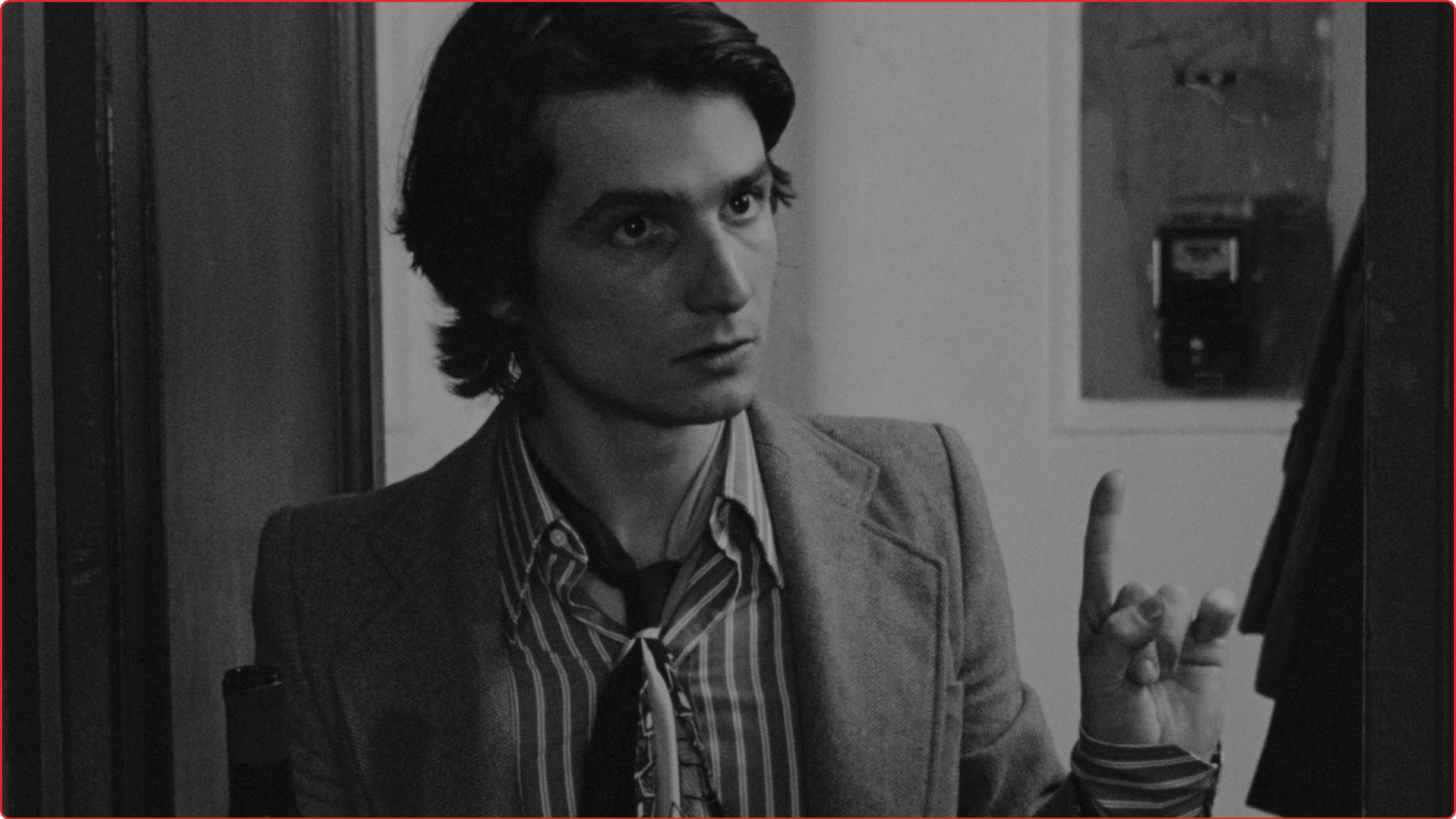

Jean-Pierre Léaud at the Cannes Film Festival in 1959

THERE IS NO OTHER ACTOR like Jean-Pierre Léaud. Since the age of 14, when he first appeared as François Truffaut’s eternal Lost Boy, Antoine Doinel, in The 400 Blows (1959)—a role he played four more times—Léaud has occupied a unique place on screen, decade after decade. He carries within him a lived history of French cinema and of film itself. From the child of the New Wave, he became a kind of paternal or enabling figure to subsequent generations, and a talismanic element for directors from every part of the world. This could be a heavy burden, but he bears it with grace. Léaud, now 79, lives in and for cinema and has always seen himself as a vessel for his director, in his own very specific, idiosyncratic way. If he is sometimes viewed as representative of a period in film history, he also seems to exist outside time.

Melvil Poupaud, who made two films with him, calls him “one of the rare actors, maybe with Bruce Lee, who has his own theory about acting.” Léaud has long been an improviser, but he has developed an approach to preparation that involves memorizing and internalizing his dialogue so completely that it almost becomes part of his body. He has a distinctive way of speaking, sometimes declamatory, often forceful or poetic, and a suite of familiar gestures, including the brushing back of his hair, and an emphatic use of the right hand that often punctuates movement and speech. Some of his gestures recall the vocabulary of silent cinema; others are manifestly his own. These elements transform themselves from one role to another.

Speed is of his essence. Writing on his frenzied performance in Jerzy Skolimowski’s Le Départ (1966), the critic Manny Farber compared him to “a pair of scissors gone angrily out of control.” Léaud can at times project almost cartoonish energy, functioning as both the Roadrunner and the Coyote: compulsive forward propulsion co-existing with the melancholy, doomed pursuit of a desired object. He can also convey stillness, contemplation, oneiric rapture. Even in the most devastating of his performances there are moments of sheer comic absurdity or unexpected delicacy.

Made in U.S.A. (1966)

MADE IN U.S.A. (1966)

Between 1964 and 1968, Léaud worked in various capacities with Jean-Luc Godard. He was a lead in Masculin Féminin (1966) and La Chinoise (1967), and an assistant and actor in small, sometimes uncredited roles in other films. Made in U.S.A. was a project conceived in haste and shot in a hurry by Godard to help out a producer friend. It is a riveting piece, a vivid collage of politics, pop art, Hollywood noir, a reflection on cinema, the close-up, activism, and absence. It stars Anna Karina, Godard’s soon-to-be ex-wife, in her final feature with him.

Léaud is one of four assistant directors credited on the film, and he has a small role as a character (named for director Don Siegel) who is trailing Karina’s trench coat-clad investigator. He looks boyish and eager; he wears a powder blue suit with a large lapel badge that reads “Kiss Me I’m Italian.”

He might not have much to do, but when he gets his chance—and it’s not really a spoiler to say that it is a death scene—Léaud gives it his all. Beneath a voiceover from Karina, Léaud mimes parts of her narration like a silent-movie star playing charades, then gives Singin’ in the Rain “make ’em laugh” style energy to his long-drawn-out, comically overblown final moments as he gestures, lurches across the space, rolls along the ground and calls for his mother. In Masculin Féminin, the death of Léaud’s character, Paul, took place off screen. Here, it’s front and center.

Stolen Kisses (1968)

STOLEN KISSES (1968)

After filming François Truffaut’s Stolen Kisses (1968), Léaud’s co-star, Delphine Seyrig, wrote to the director to say how much she had enjoyed her scenes with him, and how good he was at improvisation. This was Truffaut’s first film to feature Antoine Doinel as an adult, although he remains an obliging, naive outsider in a world whose rules he never truly comprehends. From the outset he is a figure of hectic motion, in flight, on the move, elusive yet conspicuous, whether he’s rushing to an appointment, exiting in excruciating embarrassment, or—when he is working as a private detective on a surveillance mission—desperately zigzagging, trying not to be spotted. And, in an unforgettable scene, he can be frantic even when standing still. Antoine, gazing intently at his reflection in a bathroom mirror, repeats his full name and the names of two women he is fixated upon, over and over and over with increasing intensity and characteristic insistent gestures. It is simultaneously incantation, introspection, obsession, absurdity, a feverish union of language and the body.

The Mother and the Whore (1973)

THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE (1973)

When it was first screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973, Jean Eustache’s epic, extraordinary feature divided audiences, and continues to do so. The Mother and the Whore is a long, harrowing account of sexual and cultural politics, disengagement and despair, seemingly random but also carefully constructed, a work with a complicated relationship to authenticity, nostalgia, memory, and longing. One of the film’s leads, Bernadette Lafont, called it “Les liaisons dangereuses in the 20th century.”

It remains hard to grasp in many ways: no matter how often you have seen the film, you discover new things about it every time. Yet one thing is always clear: Léaud’s character, Alexandre, caught between two women, or perhaps three, has made the performance, above all the play of words, an essential element of his projected sense of self. Léaud conveys, in painful detail, what happens when this all begins to fall apart. At the outset, it seems that he will never be at a loss for words; by the end, he is rendered more or less mute.

The shoot was a grueling experience for Léaud, in part because of Eustache’s insistence that Alexandre’s long monologues be delivered as written, down to the last comma; he would start the scene again if there were even the smallest deviation.

I Hired a Contract Killer (1990)

I HIRED A CONTRACT KILLER (1990)

Finnish filmmaker Aki Kaurismäki makes no bones about the extent of his admiration for Léaud. “You need maybe five John Waynes and three Robert Ryans to match one Jean-Pierre,” he suggests in Serge Le Péron’s excellent documentary on the actor, Léaud l’unique (2001). Kaurismäki had already enthusiastically imitated Léaud in a 1981 film called The Liar, co-directed by his brother, Mika. Then, in his eighth feature, he directed his hero in a lead role.

I Hired a Contract Killer is a beautifully judged collaboration—deadpan, melancholy yet soulful—in which Léaud plays the isolated, self-contained Henri, who has just lost his job at a government utility and decides to end it all. After two suicide attempts go awry he hires a hitman to do it for him. A series of belated discoveries causes him to change his mind, but it appears to be too late to cancel the hit. Léaud doesn’t over-play Henri’s shift in perspective from despair and acceptance to something else, and around him Kaurismäki creates a bleak, crumbling, mysterious yet oddly familiar world, an East End dreamscape that seems to exist in several different eras at once. Small treats along the way include the figure of a contract killer with intimations of his own mortality; Joe Strummer playing in a pub; Serge Reggiani making hamburgers; and Kaurismäki in an uncredited cameo as a street vendor selling sunglasses, sharing the frame with his leading man.

Irma Vep (1996)

IRMA VEP (1996)

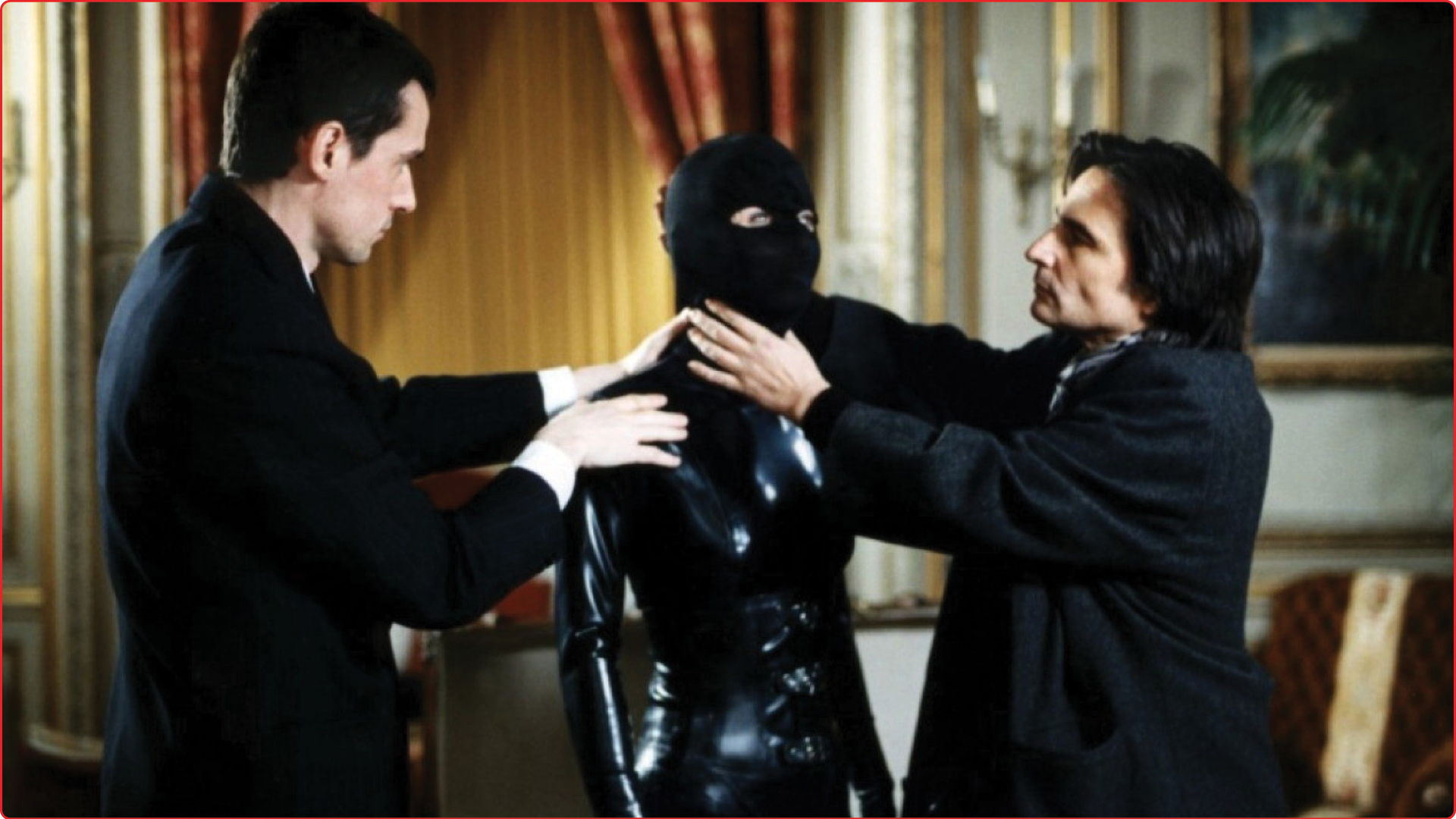

Olivier Assayas’s playful, exhilarating Irma Vep is one of many movies in which Léaud has had a role as an actor or director: others include Day for Night (1973), Last Tango in Paris (1972), The Pornographer (2001), Just a Movie (1985), The Lion Sleeps Tonight (2017), The Rise and Fall of a Small Film Company (1986), Visage (2009), and I Saw Ben Barka Get Killed (2005). In Irma Vep, he plays René Vidal, a once-acclaimed, now struggling filmmaker determined to remake a legendary work of French silent cinema with Hong Kong star Maggie Cheung (playing a fictional version of herself) as the central character. At first Maggie can’t see why he has chosen her but by the end she is the only person who seems to understand what he has been striving for.

In his later films, Léaud’s spiritual, meditative qualities emerge more clearly in his performances. Here, he plays René as a dreamer searching for a cinematic language and truth amidst the quotidian chaos of a film set already in crisis. There’s a wonderful scene in which he’s talking in English to Maggie about her role. He is confiding, intense, punctuating his words with emphatic gestures. He talks of the need for her to play herself, and of the place of silent cinema in his vision. Don’t do more, do less, he says. “You must respect the silence.” And at the same instant he darts sideways to retrieve a large plastic Coke bottle from which he takes a swig. It is a moment of glorious poetic eccentricity from a character and an actor who can never truly be confined or defined, who remains an enigma.

The Death of Louis XIV (2016)

THE DEATH OF LOUIS XIV (2016)

Albert Serra’s work started its life several years earlier as an ambitious installation planned for the Pompidou Centre. It involved Léaud, a glass cage suspended from the ceiling and a real-time performance of the king’s last 15 days. Although the project fell through, many of its elements emerged on screen in The Death of Louis XIV.

It is almost entirely a bedchamber piece. Often it is wordless, punctuated by the ticking of a clock or the sound of breathing. Louis is frail, in pain, scarcely able to move, sometimes barely awake. Courtiers attempt to maintain ritual and protocol. Doctors gather, bicker, inflict treatment on the unfortunate patient. Apart from occasional moments upright early in the film, Louis is supine virtually throughout. But Léaud is a remarkable, compelling presence, embodying not only the king but also the passage of time itself. His death, when it comes, is almost imperceptible.

In 1966, Roberto Rossellini made a film about the young Louis that provides an intriguing contrast to Serra’s. Rossellini’s The Taking of Power by Louis XIV shows how a young monarch assumes control and turns himself into the center of French political, fiscal and cultural power. Yet it ends with Louis (Jean-Marie Patte), in a rare moment of solitude at court, reading aloud from François de la Rochefoucauld’s famous Maxims, and repeating one that seems to have lodged itself in his mind: “Neither the sun nor death can be gazed upon fixedly.” Fifty years later, Léaud’s performance of Louis in his final days almost feels like some kind of uncanny response to this moment and its unsettling challenge.

Jean-Pierre Léaud at the Cannes Film Festival in 2016

Share: