Column

[wpbb post:title]

Column

BY

[wpbb archive:acf type=’text’ name=’byline_author’]

In his column Futures and Pasts, Metrograph’s Editor-at-Large Nick Pinkerton highlights screenings of particular note taking place at the Metrograph theater. For the latest entry, he recommends Karen Arthur’s simian psychodrama, The Mafu Cage (1978).

The Mafu Cage screens at Metrograph from Saturday, August 17 with Karen Arthur in attendance, as part of Also Starring… Carol Kane.

When a Stranger Calls (1979), Fred Walton’s feature-length riff on the sleep-away camp story-time perennial about a babysitter and the maniac ringing her from upstairs, starring Carol Kane as the menaced sitter, takes advantage of the 26-year-old actress’s ample ability to convey mounting fear with her saucer-wide eyes. Far more people bought tickets for Walton’s film, a modest box-office success, than for another psychological thriller Kane starred in the previous year, Karen Arthur’s The Mafu Cage, though it seems entirely possible Walton might have been inspired in his casting by a viewing of Arthur’s film, which gives abundant evidence of Kane’s ability to command the screen without the aid of a partner-or human partner-when necessary, essential in a movie that, like Stranger, demands its lead actress spend the first reel performing opposite a telephone receiver. But while Stranger‘s employment of Kane as a woman terrorized and terrified is certainly effective, what Arthur did with this physically unimposing actress with a mousy warble of a voice is inspired; as in Cindy Sherman’s Office Killer 21 years later, in The Mafu Cage, Kane’s character is the one you should be afraid of.

This fact is not immediately evident; The Mafu Cage is a movie that reveals itself only gradually, like a pungent exotic hothouse plant slow to flower. Its opening credits run over a series of leisurely pans surveying the contents of a home filled with such vegetation, as well as African ceremonial masks and musical instruments, and the skins of leopards and lions serving as decorative rugs. This might, one imagines, be the well-appointed home of an agent of His Majesty’s Colonial Services in the early 20th century, but in fact it’s the Carpenter family manse, tucked away somewhere in the hills around Los Angeles. Kane’s character, Cissy Carpenter, is the adult daughter of an anthropologist, apparently prestigious in his field in life, deceased for an undisclosed number of years; she now lives in the old homestead with her buttoned-down older sister Ellen (Lee Grant). Ellen holds down a job as an astrological photographer, has an office in the Griffith Observatory, and has begun an ongoing flirtation with her co-worker David (James Olson), who’s possessed of a laid-back self-confidence and wears his receding hairline well. Cissy stays close to the homestead, keeping its lush indoor jungle watered and fetishistically preserving the place as a monument to their father’s memory. And then, too, she has her mafus.

Before learning what, exactly, the “mafu” referred to in the film’s title is, we hear the word from Kane’s Kewpie doll lips several times. The first indicator that Cissy might not be all there comes around the time when Ellen, arriving home one evening, is compelled to assist her keyed-up sister, who we’ve seen bloodied and cleaning up from some mysterious scrape, bury a deceased mafu in a makeshift cemetery on the grounds filled with rude headstones for other mafus who’ve, presumably, met similar fates. Something bad happened to the mafu; Cissy seems to have lousy luck with her mafus. They live, it seems, in a barred-off room in the house that resembles a cage in a zoological garden, and then one after another they find their way to the boneyard. The corpse the two women are seen dragging to burial, under cover of darkness, is about the size of a young boy or girl, but its limp body doesn’t quite move like that of a human.

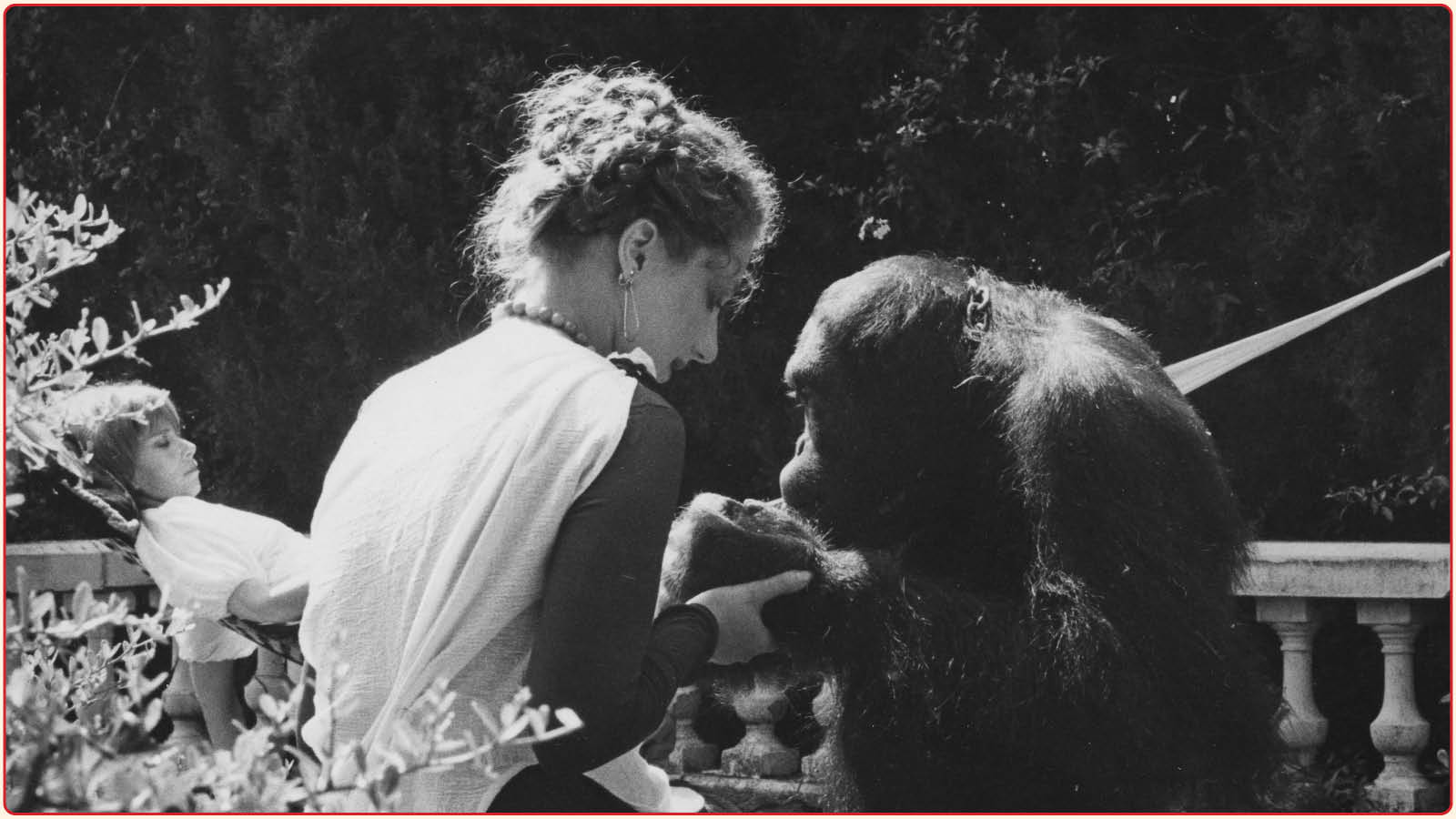

Mafu, it transpires, is the catch-all name Cissy gives to the higher apes who are repeatedly given to her care to sit as artist’s models in her continuation of her father’s research, and that seem to keep dying under her watch. By most reckonings this doesn’t make Cissy a murderer, exactly; a viewing of Frederick Wiseman’s Primate (1974) is recommended for anyone who would like to see what you can get away with doing to an ape in the name of research. We ” kill” animals, legally and otherwise, but “murder” is a title reserved for the killing of human by human-though the case of killing a mafu is rather uncomfortably close, as ape is uncomfortably close to man. Still, no one can stay mad at Cissy when she takes on the air of a flummoxed child caught with her hand in the cookie jar, and so the cycle continues.

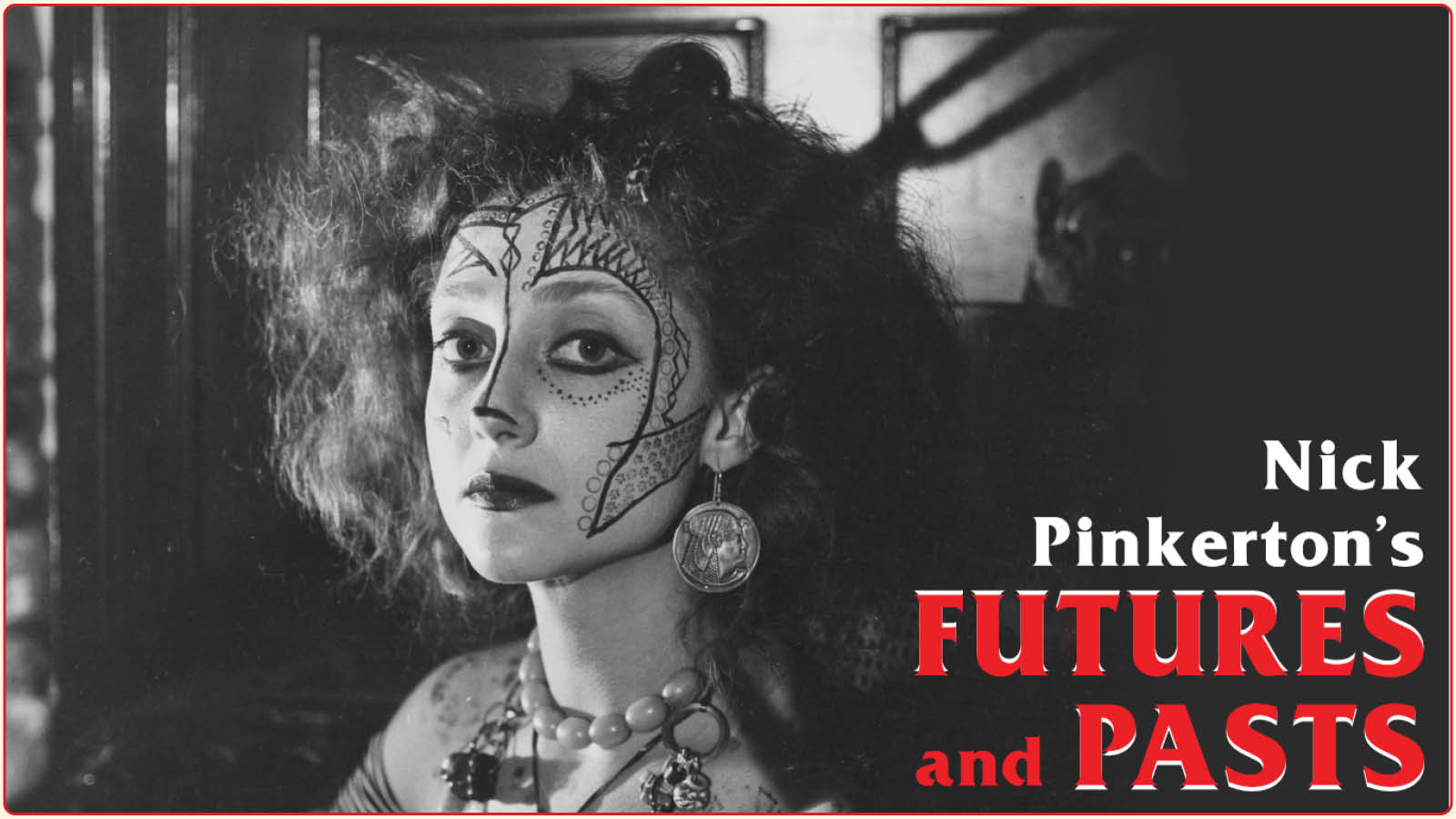

Photograph by Daniéle Légeron. Courtesy of Karen Arthur.

The sisters’ godfather, a genial zoologist with the rubicundity of a secret lush, Zom (Will Geer), is the operator of a seedy wildlife sanctuary and dealer in exotic animals who, out of a misplaced sense of obligation to the girls, has for years kept Cissy stocked with fresh mafus. Her most recently disposed of mafu is succeeded by a handsome orangutan (identified in the credits as Budar), an endangered species, a rare and exotic find, with whom she becomes madly enamored-for a time, at least. The two cavort together through a too-brief romance, an idyllic spell of laughter and languor… but then the ape gets a little too rambunctious, as apes will, and Cissy is forced to beat him to death with a length of chain, a scene Ellen witnesses with horror, seeing firsthand, finally, the fate that has befallen so many other mafu.

Cissy can’t keep her mafus alive, but it seems she can’t live without one either, so when Zom isn’t forthcoming with a fresh specimen after the orangutan debacle, Cissy goes off book. Ellen’s workplace love interest, doggedly hopeful David, stops by the house while Ellen is away on a work trip, doing whatever it is that astrological photographers do, and finds Cissy home alone minding the fort. David has heard nothing about Cissy and her proclivities from Ellen, understandably tight-lipped as regards her unusual domestic existence-which, we’ve seen, includes the occasional interlude of incestuous petting, one possible reason for Ellen’s hesitance to remand her sister to the care of professionals-so he flirtatiously treats the kid sister as a harmlessly “kooky” free spirit. But after a couple of glasses of vino and some frisky frugging to field recordings of African tribal ceremonies, damned if David don’t wind up shackled in the mafu cage, addressed by Cissy as “Mafu,” like so many captive specimens before him.

The Mafu Cage was the second feature by Arthur who, after directing a 1976 episode of the ABC miniseries Rich Man, Poor Man Book II, had recently become only the third woman to be granted membership in the Directors Guild of America. (The second, Ida Lupino, had joined back in the 1950s.) Born Karen Jensen in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1941, Arthur was raised by her mother, an interior designer, her father having left at the time of her birth. At age eight, her mother relocated the family to Florida; by 15 she was dancing as a soloist in the Palm Beach Ballet company. Arthur had made her way to Hollywood by the mid-’60s, popping up in bit parts in television and in films. Her first role in a theatrical feature was in 1967’s A Guide for the Married Man, directed by Gene Kelly, whom she would later describe as a “miserable prick.” Determined to eventually control her own destiny, Arthur took a six-week course in filmmaking at UCLA in 1971, where she recalls receiving encouragement from teaching assistant Penelope Spheeris, and emerged with a 15-minute short, Hers. Come 1974 Arthur was in the inaugural class of the Directing Workshop for Women at the American Film Institute, founded by the multi-hyphenate Jan Haag, and it was while working as an AFI intern on the set of Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975) that she met two crucial collaborators: John Bailey, pulling focus on Penn’s film for cinematographer Bruce Surtees, and Bailey’s wife, Carol Littleton, an editor who’d been cutting her teeth in commercial work.

Arthur, Bailey, and Littleton pooled their resources to make Arthur’s feature debut, 1975’s Legacy, a film that in some regards feels like a dry run for The Mafu Cage. Both films featuring much the same above-the-line talent (Bailey, as cinematographer, under his preferred credit “visual consultant”; Littleton, as cutter; as well as composer Roger Kellaway) and both films are rather claustrophobic affairs depicting women in states of extreme mental deterioration, caroming off the walls of homes they never seem to leave-in Legacy, a neurotic, vitriolic, sexually frustrated upper-class Texas WASP Bissie Hapgood, played by Joan Hotchkis. Both also have their origins in live theater. Legacy, which won a First Feature prize at the Locarno Film Festival, adapts Hotchkis’s one-woman play of the same title for the screen, which the triumvirate of Arthur, Bailey and Littleton had seen together.

Photograph by Daniéle Légeron. Courtesy of Karen Arthur.

The Mafu Cage, whose screenplay was penned by journeyman television actor, writer, and former boyfriend of Arthur’s, Don Chastain-the Carpenter girls’ parents, glimpsed briefly in a keepsake photo, are “played” by Chastain and Arthur-is a free adaptation of Toi et Les Nuages, a play by Éric Westphal first performed in 1971 at the Théâtre de l’Athénée in Paris, with Anna Karina and Eléonore Hirt sharing the stage as the strange sisters. Arthur had acquired the rights to Westphal’s play after she’d seen a production in Cambridge, England. The film would eventually be financed independent of studio support, with funds provided by Gary Lee Triano, a real-estate developer from Tucson, Arizona, here making his first and final venture into the pictures racket, a man best remembered today for being blown to pieces in 1996 by a pipe bomb which, after a sensationalistic 18-month trial, it was determined had been put in his car on the order of his ex-wife.

A 1978 Los Angeles Times profile of Arthur states it was with a combination of the “hard sell and gentle, affectionate persuasion” that the filmmaker convinced Triano to place “unlimited funds” at her disposal, while also securing rent-free use of the principal location, a sizable estate in the Los Feliz neighborhood convenient to Griffith Park and the Observatory, from its owners. That “unlimited funds” is almost certainly an exaggeration-The Mafu Cage is by no means a cut-rate production, but neither is it a lavish spectacle, and most reports seem to put the budget at a modest million. Still, the finished film has the feeling of having been made with a free hand, and it seems altogether possible that some of this freedom was possible because Arthur was backed by a financier who was not, properly speaking, a producer at all, someone likely more concerned with the finer points of Pima County building codes than giving scrupulous notes. (Arthur had attempted and succeeded in finding potential studio backing but, as she told the Times, “the things they wanted were alien to what I felt the film was.”)

Arthur and Chastain allowed themselves to take liberties with the source material. The chamber drama is opened up slightly, with scenes at the Observatory and Zom’s nature preserve, played by “Africa USA” in Acton, California. (Africa USA was also a filming location for Tippi Hedren and then-husband Noel Marshall’s injury-plagued, six-years-in-the-making passion project Roar (1981)-another film, in its way, about unhealthy obsession with wildlife-and is today the home of Hedren’s impressive collection of rescued large cats.) Both central characters also received new vocations. The Cissy character, in the play a writer, became an artist for the movie. Explaining the change, Arthur stated “writing is boring for film,” but that she “had seen in Bellevue and in London people who were on the brink of sanity who drew because they couldn’t talk about their psychotic experiences, so they drew them and I found those paintings so original, so frightening, so Bacon-esque.”

The artist responsible for Cissy’s pen-and-ink drawings in The Mafu Cage, as well as the sphinxlike portrait mural that she is seen daubing on the wall behind her sister as she wastes away in despairing captivity late in the film, is one Roger Landry, a practicing art therapist evidently well versed in the artistic self-expressions of the mentally ill. Little information is available about Landry, but his contributions to the film-a particularly haunting image of Budar chained to the wall in his room, a single malevolent eye and fanged mouth visible in the darkness of a passage beside him; a balefully glaring portrait of something humanoid peering from behind what appears to be a screen-are tremendously effective, rivaling John Decker’s original works in Fritz Lang’s Scarlet Street (1945) as artistic manifestations of a disturbed psyche custom-made for a film.

When the five-week shoot for The Mafu Cage began in July of 1977, Kane, who had been only fitfully employed in films in the first half of the decade, was in higher demand, Academy Award-nominated in the Best Actress category for her performance in 1975’s Hester Street. It was that film’s director, Joan Micklin Silver, who first introduced Arthur to the actress. Given the scarcity of high-profile female filmmakers in the 1970s, it seems not coincidental that Kane would work with three in relatively close succession-the third being Catherine Binet’s 1981 Les Jeux de la comtesse Dolingen de Gratz (The Games of Countess Dolingen), one of the unsung masterpieces of ’80s French cinema. Kane’s co-star, Grant, was a longer established quantity; she’d been nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her debut role as a teenaged shoplifter in William Wyler’s 1951 Detective Story, and had recently won that same award for playing the older mistress of Warren Beatty’s lothario hairdresser in Hal Ashby’s Shampoo (1975).

It’s easy to overlook Grant’s work in The Mafu Cage; the role of Cissy is the showy part of the double act, but the brittle forbearance that Grant’s performance exemplifies, a dutiful indulgence that finally emerges as a fatal flaw accompanied by a tight smile that frequently looks like it’s suppressing a scream, is a finely tuned straight-woman counterbalance to Cissy’s rowdy recklessness. Kane’s Cissy is a creature who can be by turns both sweetly, childishly ingratiating and feral. She has a positive passion for playing dress-up, routinely dipping into a seemingly bottomless stock of African tribal regalia and even caking herself from head-to-toe in ocher otjize like a Himba woman before braining David with a club-“cultural appropriation” is not a part of Cissy’s vocabulary-and her moods are as changeable as her outfits. One minute she’s sipping bubbly with her orangutan on a honeymooners picnic-the scene is pointedly crosscut with Ellen and David consummating their relationship on the stairs leading to the Observatory telescope-the next she’s vitriolically berating the poor creature with her favorite epithet, “dumbshit,” a reliable tell that she’s on her way to another violent episode.

Photograph by Daniéle Légeron. Courtesy of Karen Arthur.

When Cissy wears her thick mane of ginger hair down-it’s the first thing we see of her, hanging like a curtain from a hammock she’s reclined in-she recalls Rossetti’s muse and model, Fanny Cornforth, and there is something Pre-Raphaelite in the cloistered, bathysphere world she lives in, unstuck from time and space. The trappings in the Carpenter home evoke not an idealized Quattrocento, but a fantasy of an Africa as remembered from a girlhood spent among the Ituri Forest pygmies and romanticized at a distance. Production designer Conrad E. Angone, serving in such a capacity for the first time, was an appraiser and dealer in Native American art, able to leverage his connections to borrow pieces from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the UCLA Museum of Private Collections, and various other sources-another of the bits of low-budget ingenuity which distinguish the production.

Alas, the present fails to conform to the perfection of yesterday when daddy was alive and all well in the world, and Cissy’s rages at this fact eventually consume her dumbshit mafu sister and, finally, even herself, a meltdown Kellaway accompanies with the most violent of the discordant poundings on a “prepared piano,” à la John Cage, that periodically make a cacophony on the film’s soundtrack. (These piano improvisations were collected and released on vinyl in 2018, as The Mafu Dances.) This bleak, bludgeoning climax no doubt came as a bit of a shock to viewers in later years who rented the movie under VHS release titles My Sister, My Love or Deviation in sweaty palmed anticipation of some salacious women-in-chains action.

In spite of an auspicious premiere in the Director’s Fortnight section at Cannes, The Mafu Cage‘s initial public release was a letdown. After a frustrating attempt at self-distribution the film was sold to Jerry Gross Organization-its founder and namesake’s second act, his previous company, Cinemation Industries, having been one of the largest purveyors of softcore smut before its 1975 bankruptcy-who changed the title to Don’t Ring the Doorbell in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to draw in the grindhouse crowd. A 1978 profile of Arthur, published before the film’s stateside opening, offers a portrait of the filmmaker in her Hollywood Hills home, brimming with optimism and confidence, a new four-picture deal with Universal under her belt; with her “mane of shoulder-length chestnut hair, gray eyes and… determined chin,” it reports, she “would have probably been played by Katharine Hepburn in a ’30s movie about career girls.” (The writer is perhaps thinking of 1933’s Christopher Strong, directed by the first woman to receive a DGA card, Dorothy Arzner.)

By the time of a 1982 profile, also for the Los Angeles Times, none of those four pictures had come to fruition, and Arthur had found her métier in TV movies. Preparing to shoot one such project, the three-part, six-hour Australian miniseries Return to Eden, she vents her frustration with the film industry: “I don’t want to make little films anymore,” says Arthur, “There’s just no art market for American independent filmmakers in this country.” Arthur’s final theatrical feature, the erotic thriller Lady Beware, begun at Universal in 1978, would finally be released in 1987 after passing through “100 homes, 17 drafts, and eight writers,” though her relationship with the producers was less than cordial after a lascivious re-edit adding significantly more footage of star Diane Lane in the nude.

In spite of such disappointments, Arthur remained steadily employed and by all accounts fulfilled directing television into the late aughts, leaving much to discover for the diligent auteurist. As to Arthur’s sophomore feature, it remains a singular object. The Mafu Cage can be placed within a tradition of dramas of escalating derangement occurring in a few imprisoning rooms; there is Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965), and of course the sibling rivalry-turned-deadly of Robert Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962)-cited, pejoratively, by a contemporary English review of Arthur’s film-and various imitations by Aldrich himself (1964’s Hush… Hush Sweet Charlotte), Curtis Harrington (1971’s What’s the Matter with Helen? and Whoever Slew Auntie Roo?), and others, but it doesn’t feel much more akin to any of these titles than it does to the other major orangutan movie of 1978, Clint Eastwood and James Fargo’s Every Which Way but Loose.

The unique qualities of The Mafu Cage I take to be symptomatic of the relative autonomy in which it was made. Most movies, or at least most made with money from by a person or persons aspiring to recoup their expenses, are hobbled before they arrive at the starting gate. Before the crucial check clears the feedback starts coming; notes on how motivations can be clarified, characters made more sympathetic, developmental arcs polished to an immaculate shine-in short, how the raw materials of the proposed film can be finessed to a point where they’re likely to produce something that “works” in a way that a million other movies have “worked” before. Such a system doesn’t encourage the production of films that buck orthodoxy in any way, much less films about adult sisters, one of whom spends a significant portion of her screentime screaming bloody murder about mafus, but thankfully the occasional outlier slips through the cracks.

Nick Pinkerton is a Cincinnati-born, Brooklyn-based writer focused on moving image-based art; his writing has appeared in Film Comment, Sight & Sound, Artforum, Frieze, Reverse Shot, The Guardian, 4Columns, The Baffler, Rhizome, Harper’s, and the Village Voice. He is the editor of Bombast magazine, editor-at-large of Metrograph Journal, and maintains a Substack, Employee Picks. Publications include monographs on Mondo movies (True/False) and the films of Ruth Beckermann (Austrian Film Museum), a book on Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Fireflies Press), and a forthcoming critical biography of Jean Eustache (The Film Desk). The Sweet East, a film from his original screenplay premiered in the Quinzaine des Cinéastes section of the 2023 Cannes Film Festival.

Photograph by Daniéle Légeron. Courtesy of Karen Arthur.