[wpbb post:terms_list taxonomy=’category’ html_list=’no’ separator=’, ‘ linked=’yes’]

[wpbb post:title]

Beijing Watermelon (1989)

[wpbb post:terms_list taxonomy=’category’ html_list=’no’ separator=’, ‘ linked=’yes’]

BY

[wpbb archive:acf type=’text’ name=’byline_author’]

On Nobuhiko Obayashi’s newly restored, slippery gem of a film.

Beijing Watermelon opens at Metrograph on Friday, June 7, as part of Nobuhiko Obayashi x 3.

Despite having made in excess of 70 films over six decades, Nobuhiko Obayashi was all but unknown in the West for much of his life. This has changed in recent years, after screenings and re-releases of his most well-known title, the raucously inventive haunted house comedy Hausu (1977), and his late-career Anti-War trilogy (2011’s Casting Blossoms to the Sky, 2014’s Seven Weeks, and 2017’s Hanagatami), have seen attention steadily rise outside of Japan. Since his death in 2020, shortly after the completion of his opus, the WWII-set fantasy drama epic Labyrinth of Cinema (2019), his profile has grown still further-yet these works only represent a fragment of the filmmaker’s vast range.

Emerging as an experimental filmmaker at the start of the 1960s, Obayashi made shorts on 8mm and 16mm alongside film club colleagues Donald Richie and Takahiko Iimura, before being noticed by the mammoth Japanese ad firm Dentsu, with whom he made thousands of commercials during the 1970s. When Toho approached him to make a feature, he offered them the script for Hanagatami, but they wanted a blockbuster and got Hausu instead. It became Obayashi’s first feature and a landmark in Japanese art cinema. After this, Obayashi worked relentlessly, directing, more or less, one or two films per year up until his death, making everything from coming of age dramas, mysteries, sci-fi sagas, and fantasy epics, to comedies, documentaries, and everything else in between. He was continually, explosively innovative. Employing an array of forms of visual trickery and ingenuity, such as his pioneering usage of green screen and throwback matte effects, Obayashi left behind him a body of work that is distinguished, most immediately, by a singularly poppy stylistic flair.

Beijing Watermelon (1989)

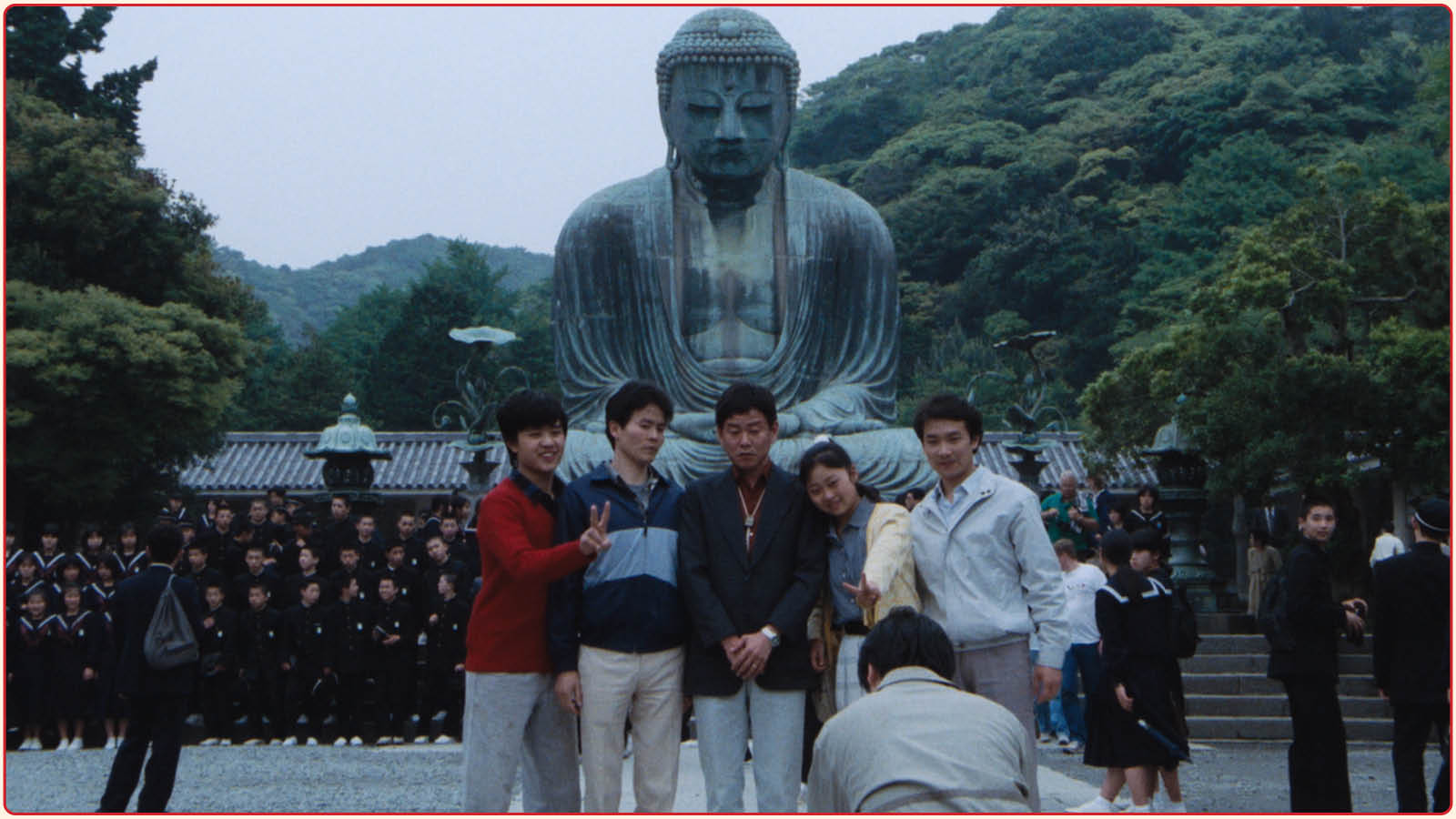

Set against these films, Beijing Watermelon (1989) stands somewhat apart. Free of much of Obayashi’s signature visual pizazz, it comes across as a fundamentally ordinary film about finding connections and commonalities despite differences of nationality, culture, and class. A greengrocer, Shunzo (played by the popular though then little-known Japanese comedian Bengal), together with his wife, Michi (Masako Motai) and family, runs a small, specialist fruit and vegetable store in Funabashi, Chiba, where he befriends a group of impoverished Chinese exchange students. Within this seemingly straightforward set-up, the imaginative side of Obayashi is still much on display-primarily in an out-of-nowhere, fourth wall-collapsing third act, and his surreptitious treatment of events occurring in China at the time of its production (to be detailed more later). And yet, it all comes packaged in a sweet slice-of-life family drama that sometimes verges on saccharine, its form indebted to Yasujirō Ozu, not usually an obvious reference point for Obayashi’s eclectic body of work.

Scenes play out almost entirely in fixed-position, pillow-esque, medium shot long takes, with groups of characters packing every corner of the frame, scrabbling about, cooking, eating, and constantly talking over one another, the sound design overlapping like in a Robert Altman film. Across these tableaux, whether showing coming-togethers taking place in the grocery store front, the market floor, student dorms, or the family’s living room, each moment overflows with an organic, lived-in realism. As such, Beijing Watermelon makes an argument for Obayashi’s films to be understood as not only works replete with outlandish formal flourishes and invention, but also as notable (much like his Anti-War trilogy, made in response to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami) for the unabashed humanism at the core of them all, regardless of genre or approach.

Shunzo, Michi, and the students first come into contact in a scene wherein aspiring architect Li (Wu Yue) is seen lurking around their store, eyeing and handling vegetables but never buying anything. After suspecting the young man might be some kind of spy, Shunzo talks to Li and finds out that he is a Chinese student who can’t afford to pay 50 yen for the vegetables that would have cost him the equivalent of five yen back home. The pair agree on a discount for the students, not comprehending what this generosity may end up costing the family, after Shunzo loses a round of Rock, Paper, Scissors-a game he calls “janken,” and that Li knows by a different name. The film is full of such gentle signifiers of cultural difference and communion. (In another funny development, Shunzo buys a Chow Chow, a goofily fluffy dog breed that hails from Northern China. “A new encounter means another farewell,” he says, vocalizing one of the film’s main themes.)

Beijing Watermelon (1989)

This discount agreement, a trade pact of sorts, starts an entanglement that touchingly bridges the gaps between the two countries and cultures, providing the young, homesick students with an anchoring mentor figure (“Japanese Dad”) as he increasingly gifts them with cut-price produce, car rides, and guidance-a role that is clearly also filling some undefinable absence in his own life, and which causes the villagers to remark upon Shunzo’s “China fever, ” as it is becoming known around town. At the same time, this assumed paternity causes tensions at home as his friendship with the students threatens to overshadow his relationship with his own family. As explained by the intermittent narration, Beijing Watermelon is a “true story” of sorts, created after the crew met with the real-life grocer and students on whom the drama is based during the shooting of a different film, instigating a pivot. As such, some kind of bleeding between fiction and reality is ever present, emerging subtly, sometimes obliquely, at certain points throughout.

In the establishing store scene, Michi starts out as the generous patron, with Shunzo more Scrooge-like and suspicious, but as the financial tables twist over the film’s duration, the dynamic shifts. “We’re not a tourism company,” she scolds later, after the family has lost their food market buyers license and is at risk of losing their store, in part due to the many airport rides Shunzo has been offering the growing groups of visiting students that he argues are China’s new generation’s “selected few.” In a later misstep, Shunzo gifts Michi’s necklace for a student to then give to his wife. When Michi learns of this, he protests that she never wore it anyway. “When would I have had the chance?” she rightly retorts, getting at the repetitiousness of small-town retail and the limited horizons of their life. But however ruinous Shunzo’s mostly well-meaning ambassadorship may have become, Michi later acknowledges that at least something new has come to Chiba: a “Japan-China friendship.”

Beijing Watermelon (1989)

For a long while, a viewer may wonder what the meaning of all this cultural exchange might be, considering China and Japan’s long, fraught history and the distinctive economic and political situation present in both countries in the late 1980s: Japan reaching the tail end of its economic boom and China beginning a period of continuous exponential growth and globalization. A background plot point reveals that Shunzo’s father died fighting in China in the 1930s, suggesting his infatuation with the students might be a post-factum atonement of sorts. One other clue comes from the film’s date markers, which, it is revealed, do not describe when the narrative events took place but instead the period of its making. When, in the story, Shunzo and Michi travel to China for a student reunion, Bengal turns to face the camera, explaining that it was not possible for the crew to travel to the country to shoot on location, meaning the reunion scenes had to be done on a Tokyo soundstage and the airplane ones inside Haneda Airport’s pilot training simulators. As well as shifting the viewer’s understanding of what has been, to this point, a fairly traditional drama, this meta-exercise alludes to contemporary events taking place in China, now 35 years ago. The opening narration states that filming started in May 1989; the section set in Beijing was to be completed in June. The Tiananmen Square massacre had just taken place, so the shoot could not proceed as planned. “Reality is sometimes more powerful than movies,” explains Bengal, saying all that needs to be said without stating outright anything at all.

At the film’s end, a credits tribute “to our young Chinese friends” reinforces what it meant to make a story about Chinese students in that moment, emphasizing, without resorting to any political grandstanding or anything resembling a treatise, the political import present behind what may at first seem only a single-layered story of empathy across cultures and the open exchange of ideas. Shunzo says at one point, “All I did was give discounts on bok choy”; sometimes the most significant gesture is also the most modest. Obayashi, who was relentlessly productive and dedicated to his craft, was also committed to an all-encompassing humanism. His last words, “Thank you everyone”-something he apparently said on set every day-attest to this in the simplest, most moving way.

Matt Turner is a writer based in London, UK.

Beijing Watermelon (1989)