Strange Pleasures

Yekaterina Golubeva

The extraordinary performances of the enigmatic actress who transformed the femme fatale archetype on screen. Alt Divas: Argento / Dalle / Golubeva opens at Metrograph Theater on Friday, November 7.

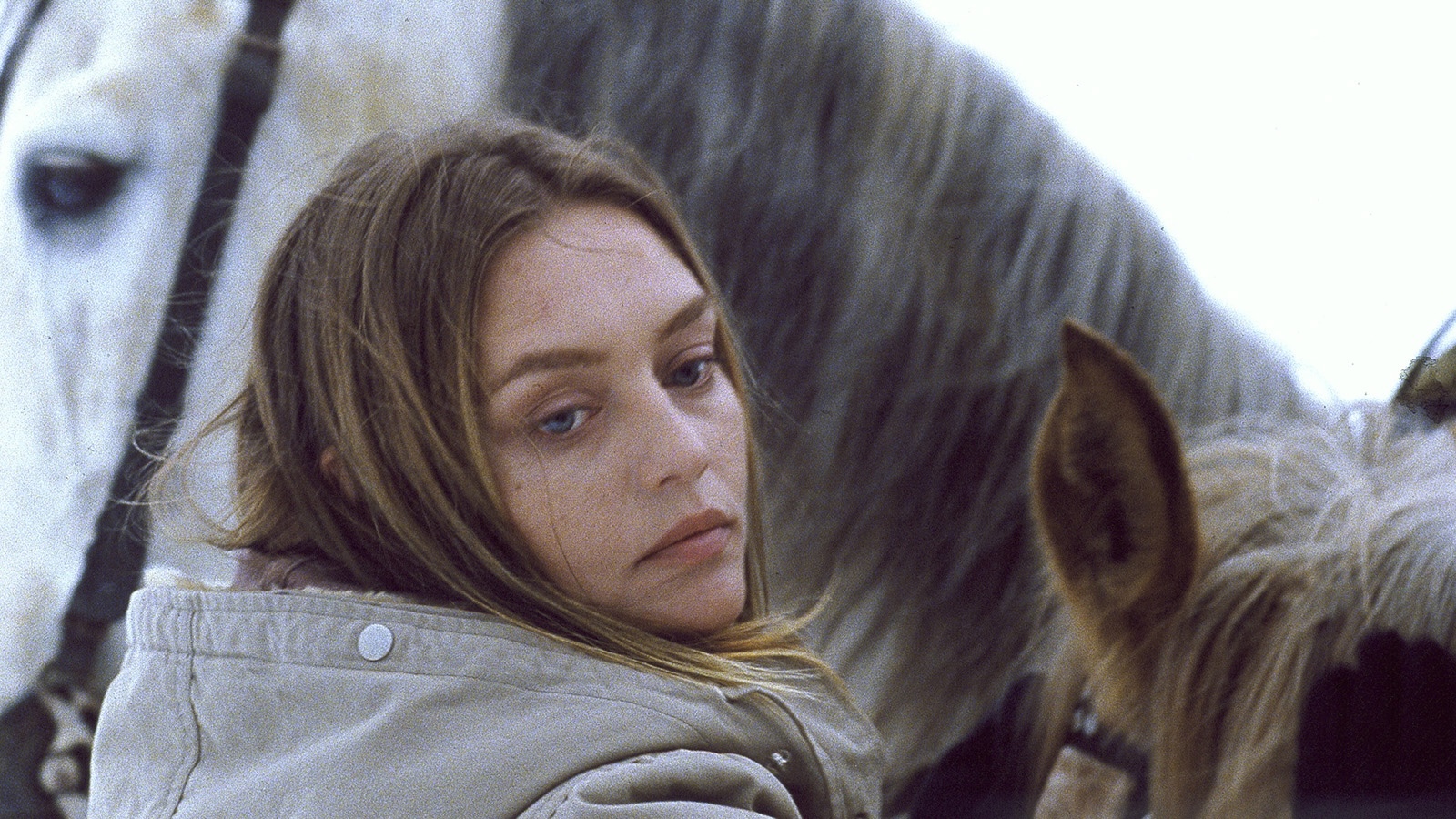

L’intrus (2004)

Share:

IN THE OPENING OF CLAIRE Denis’s I Can’t Sleep (1994), we glimpse Yekaterina Golubeva’s character Daiga driving a creaky stolen car alone through le périph into Paris’s 18th arrondissement. An ash-blonde beauty with cheekbones that could poke an eye out, she looks unfazed, smoking a cigarette as she plunges into the unknown. Five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, as former Eastern Bloc citizens scattered across the West following decades of Communist-era travel restrictions, the Vilnius-born Daiga has come to Paris—the site of new beginnings for countless immigrants and asylum seekers in the ’90s—to pursue a career on the stage, a move that echoes Golubeva’s own too-brief trajectory.

Born in Leningrad in 1966, the enigmatic actress started appearing in Russian films in the ’80s before coming to the attention of international audiences for her four collaborations with the Lithuanian director Šarūnas Bartas, her second husband. Golubeva’s breakthrough came in his debut feature Three Days (1991), which premiered at the Berlinale to great success—her melancholic sensibility meshing organically with his sparse, Tarkovskian cinema—and likely motivated Golubeva’s migration to Paris. There, she landed on the radars of arthouse heavyweights like Denis and Bruno Dumont. Leos Carax, her partner up until her death in 2011, has stated that, upon merely seeing Golubeva’s face on-screen one day for 10 seconds, he was instantly captivated.

And how could he not be? In Three Days, Golubeva plays a nameless woman who drifts through the gray wreckage of Kaliningrad, a Russian enclave between Lithuania and Poland. The film centers on Golubeva’s character and two other similarly listless young men, all of whom are simply looking for a place to sleep. Incapable of meaningful human connection, these three emotionally stunted souls continuously come together and part as they wander around dilapidated buildings and barren stretches of land, symbols of post-Soviet stasis. Golubeva’s silence, here, seems born of an inner void, as if boredom and desolation has stripped her interiority. The men seem interested in having sex with her and she consents apathetically, as if she were incapable of pleasure but still open to anything that might distract from her sorrows. In the final scene, one such intimate encounter unfolds with the camera held up to Golubeva’s face. Tears stream down her cheeks and her mouth contorts, her bared teeth gnashing, as she swings, indeterminately, from animal passion to pained exasperation. At the same time, there’s an edge to Golubeva’s seeming passivity that communicates a kind of hardened nihilism. You never think for a second that Golubeva is crying because of this insignificant man’s touch; instead, he’s a nameless mechanism for her anguished catharsis—her thoughts on everything but him as she stares out into the distance.

Three Days (1991)

Watching this film, Carax, on the heels of his break-up with his previous muse Juliette Binoche, believed he had found the missing piece for Pola X (1999), his long-gestating adaptation of Herman Melville’s Pierre; or, the Ambiguities. Golubeva would go on to play the film’s cryptic female protagonist, its source of radical, ultimately destructive creative inspiration. (After her death, Carax dedicated his 2012 surrealist fantasy Holy Motors to Golubeva, who had introduced him to the short story—E. T. A. Hoffman’s “Don Juan”—that inspired the film.) Indeed, Golubeva’s characters often make men seem small, miniatures in the face of the epic baggage she always seems to be carrying. Her haunted visage and Slavic background anchored her persona to the unravelling of 20th-century history with its cruel narratives of exile and dislocation.

In Three Days, Golubeva is in possession of a past whose vast horrors are unimaginable, but in Pola X, Carax gives her the stage to unleash her woes, in turn shattering the privileged world of Guillaume Depardieu’s Pierre, ascendant author and scion of French aristocracy. Golubeva plays Pierre’s vagrant maybe-half-sister, Isabelle, a refugee from the Bosnian Civil War. (The conflict is close to Carax’s heart; he travelled to Sarajevo during the ongoing siege to present his work to the city’s underground resistance community.) When Pierre stumbles upon her on the side of the road, he is entranced by her brooding beauty and threadbare ensemble, kindling his imagination when he recognizes her as the woman who has been appearing in his recurring dreams. Her arrival foretells ruin, sending Pierre into a decadent spiral, yet her otherworldly presence also breathes restless energy into the film, compelling Pierre to break the constraints of his monotonous existence: abandon his country villa for a derelict warehouse run by a terroristic cult, and defy his mother’s (Catherine Deneuve) bourgeois demands. In its most ravishing scene, when Pierre and Isabelle first meet and stumble through a Stygian forest cast in shape-shifting shadows, she shares horrific memories of her past in disjointed fragments, her tremulous, broken French cutting through the hush of the wilderness. Like Virgil leading Dante through the underworld, Isabelle leads Pierre through the darkness, as if encouraging him to commune with the other side. That both Golubeva and Depardieu would perish within the following decade only intensifies the film’s already violent storm of grief and desperation for viewers today.

Across her filmography, the actress was consistently, frustratingly opaque, yet enticing in her mystery. Golubeva’s Russian lilt is leveraged in both Denis’s and Dumont’s tales of displacement, where her characters’ linguistic inadequacies always seem to represent something much deeper: a kind of spiritual chasm that keeps her at arm’s length. Her first French-language movie was I Can’t Sleep, although her character is far from fluent, struggling through basic interactions with a heavy accent to the ire of several prejudiced Parisians. Even in Golubeva’s later films, such as Dumont’s California-set thriller Twentynine Palms (2003), language is an issue, with her character’s wobbly French, and even wobblier English, creating an existential rift between her and her American boyfriend. Yet Golubeva was not merely a pretty cypher for others’ projections but a woman coiled into herself, guarded and skeptical. It is perhaps this quality that makes her such a hypnotizing screen presence, even though she only appears in less than 15 feature films.

Pola X (1999)

Adding to Golubeva’s shroud of secrecy is the lack of critical writing and information available about her life and work, the sense that her story was interrupted, unfinished. Today, her name carries a somber weight given her struggles with depression, which led her to end her own life in 2011 at the age of 44, and sealed her memory in the haze of myth. Even the posthumous Russian documentary I Am Katya Golubeva (2016)—which reveals that Golubeva is survived by her mother, brother, and three children (though in a final cruel twist, Ina Marija Bartaitė, her daughter with Bartas, died in a traffic accident in 2021, aged 24)—treats her less like a dynamic human than a girl eternally disenchanted, her gloomy choice in roles forecasting her fate. We do know that Golubeva began pursuing the arts as a teenager, leaving high school early to enroll in a theater school against her mother’s wishes. Growing up in the Brezhnev-era USSR, with its high levels of cultural censorship and conservative ideals promoted by the State, may have fueled the young actress’s fascination with the Western world. Once she established herself on the other side, however, her characters would be deceived by the allure of the Occident, finding other forms of violence in their supposedly progressive new homes.

In all her films, Golubeva summons a state of lost innocence, her dark yet doe-eyed gaze tethering her to the act of mourning—if not over a life, then the belief that it could be otherwise. In Denis’s L’intrus (2004), Golubeva plays a literal ghost, an “Angel of Doom,” per Denis, who also, like Isabelle, visits the film’s protagonist, Louis (Michel Subor), in his dreams and observes him from afar. She appears in the very first shot of the film, staring forebodingly into the camera, enshrouded by moonlit blue, as she utters a kind of premonition: “Your worst enemies are hiding inside, in the shadows.” Louis is an ex-mercenary seeking out a heart transplant. It is this wrestling with bodily autonomy (or lack thereof) that fosters the conditions for the film’s porous boundaries: between past and present, reality and fantasy, life and death.

Halfway through the film, Golubeva’s specter emerges in a flesh-and-bones guise, as Louis’s point of contact in his negotiations for a new heart through the Russian black market. Subor’s own parents were immigrants from the Soviet Union, so Golubeva’s presence also teases out an ancestral dimension to the film’s blurring of time and bodies. But her phantasmal figure is not a delicate spirit, more like a smirking Grim Reaper. After Louis finalizes the transaction, we see Golubeva and a companion on horseback dragging his body through the snow in a visceral, possibly imaginary manifestation of his fears and anxieties. “You’ll never pay enough,” she mutters after untying and abandoning him in the icy field, reminding him that a new heart won’t change the conditions of his life, won’t make him less deserving of pain.

In another timeline, Golubeva might have been a formidable femme fatale, though her striking stoicism often feels like a curse. Beauty, though a source of power, can also be alienating, and in the case of Golubeva, her good looks seemed to position her as an object to be admired, obsessed over, dreamed of, rather than fully understood. Her reticence, far from a sign of weakness, is a force in her interactions. It allows us to feel her anger and frustration at the same time as it disarms and puzzles. In I Can’t Sleep, when a creep tries to pick her up on the street, Daiga doesn’t merely flee from him; her arms are crossed aggressively, and the way she sharply swerves and stomps away suggests she’s taking herself away from him for his own good, too. When she finds refuge in a movie theater, the image of a starlet staring up at the screen—enshrined by Godard’s Vivre sa vie (1962) when Anna Karina watches Joan of Arc facing her imminent execution in Dreyer’s 1928 film—comes to mind. Yet their viewings couldn’t be more different: as Daiga settles into her seat, she realizes she’s watching a pornographic snuff film surrounded by leering men. Golubeva’s unflinching scrapper has nothing of Karina’s tragic, whimsical glamour. In a sense, this scene demonstrates just exactly how Golubeva could reframe the mood, turning an iconically romantic sequence into a seedy vision of jadedness, rooted in a kind of gallows humor that a Russian gal like Golubeva must’ve understood all too well. Her expression remains placid as the men turn their heads away from the screen and lean forward to take a better look at her—until, finally, she breaks, letting loose a scoff and bursting into a full-throated cackle. We don’t get much of this lightness throughout Golubeva’s career, but when we do, it feels like an epiphany. She’s a woman who has seen it all; who prefers wielding her armor, until that moment comes when everything is stacked against you, and all that’s left to do is laugh.

Share: