Interview

Sean Baker

The director of Anora looks back at his early career.

Share:

This May, Sean Baker became the first American in over a decade to win the highest prize at the Cannes Film Festival for his new film, Anora (2024). Mikey Madison portrays the titular Russian-American exotic dancer living in Brighton Beach who enters into a whirlwind romance with a fabulously wealthy client (Mark Eidelstein) who happens to be the son of a Russian oligarch. Even independent from its plaudits, Anora feels like a culmination for Baker; it boasts the biggest budget he’s worked with to date, and is his fifth consecutive film to include a sex worker as a main character. But there is more to Baker’s career than the progressive growth in budget and prestige that the 10 years since the release of Tangerine (2015), his breakthrough film, imply.

Baker directed his debut feature Four Letter Words (2000) nearly 20 years before Tangerine, in 1996. Focusing on a group of white, male high school friends on vacation from college over the course of a single night, the film has been compared by Baker himself to the work of fellow New Jeresyan Kevin Smith. He followed this with Greg the Bunny (1999), a series of shorts made with friends chronicling the amusing antics of a leporine hand-puppet, which was scooped up by Hollywood, and made into a Fox sitcom, starring Eugene Levy and Seth Green, and produced by one of the creators of Modern Family. But instead of making the perhaps predictable career leap to mainstream television or big budget studio comedies, Baker sat out the Fox version of Greg the Bunny, and (with co-director Shih-Ching Tsou) made Take Out (2004), a film shot almost entirely in Mandarin about one day in the life of a Chinese immigrant in New York City, for a budget of just $3,000.

Since then, he has continued to be uncompromising in the films he choses; working with the budgets he can raise and, in lieu of chasing stars, casting unknowns he meets on the street or finds online. When given a tiny budget for Tangerine, he shot the film on iPhones. When Willem Dafoe signed on to his follow up The Florida Project (2017), he cast Bria Vinaite, a Baker Instagram discovery who had never acted before, as his co-lead.

Even as it moves between genres, Baker’s work is marked by an overwhelming pathos that somehow never crosses over into melodrama—a quality that comes through powerfully in Anora. Hot on the heels of his triumph at Cannes, I caught up with Baker during the New York Film Festival to look back at his career, and discuss how much of it has been the result of careful planning, lucky accidents, or merely fate. —Gabriel Jandali Appel

Take Out (2004)

GABRIEL JANDALI APPEL: There’s a gap in my knowledge about your career, and it’s the four years between Four Letter Words and Take Out. Could you help me understand how you got from one project to the other? They’re very different films. I know that Greg the Bunny also came out on Fox during that time…

SEAN BAKER: [Laughs] I had a major drug problem. I lost myself in my late twenties. And it was actually me getting sober in 2000 that got me back on the path of doing what I always wanted to do, which was make features.

Four Letter Words, that was a very personal film, but it was a young film, before I had any life experience. I needed to go through a lot, and that’s what happened between 1996 and 2000.

I was lucky enough to have Greg the Bunny, this show that came out of nowhere and was paying my rent, but then I lost Greg the Bunny for a little while because of my drug habit. They did Fox without me, when it was in development I was getting sober. Then I was on my own for a few years trying to figure out what to do with my life.

I went back to The New School because I had graduated from NYU just before the digital revolution. I was in the last class that was cutting on a Steenbeck; I had never got the training in nonlinear editing.

At The New School, I learned AVID, and that’s where I met Shih-Ching Tsou, and we decided to collaborate on Take Out. So, I guess it was in those years living in New York that I got enough life experience, enough ups and downs, to allow me to make something I was a lot prouder of.

But what if I had been part of that Fox show? What if I had stayed in Hollywood? It would have led to a very different career trajectory. A lot of times, fate and happenstance got in the way and kept me on this path, and I’m very grateful for that.

Then, later I regained the trust of my two Greg the Bunny collaborators, Dan Milano and Spencer Chinoy. I was able to come back onto the show when it returned at IFC. That was really nice, it was like a reunion. And it also paid for my second movie, Prince of Broadway (2008).

GJA: You paid for it entirely on your own?

SB: Yeah. Well, it cost only $47,000, but that’s what I made that year from Greg the Bunny so I put it right into the movie.

GJA: By the way, I’ve been sober for 10 years. I didn’t know that about you.

SB: Oh, congratulations, man. It’s something I haven’t worked into a film yet, but I’ve written a film about drug user activism that takes place up in Vancouver. It was the first time I saw something I could say about my whole experience that wasn’t already said. Because there have been amazing drug movies—Panic in Needle Park (1971), Christiane F (1981)—I thought, I’m never going to tackle my personal stuff until there’s a new topic. Maybe not the next film, but eventually, I’ll tackle it.

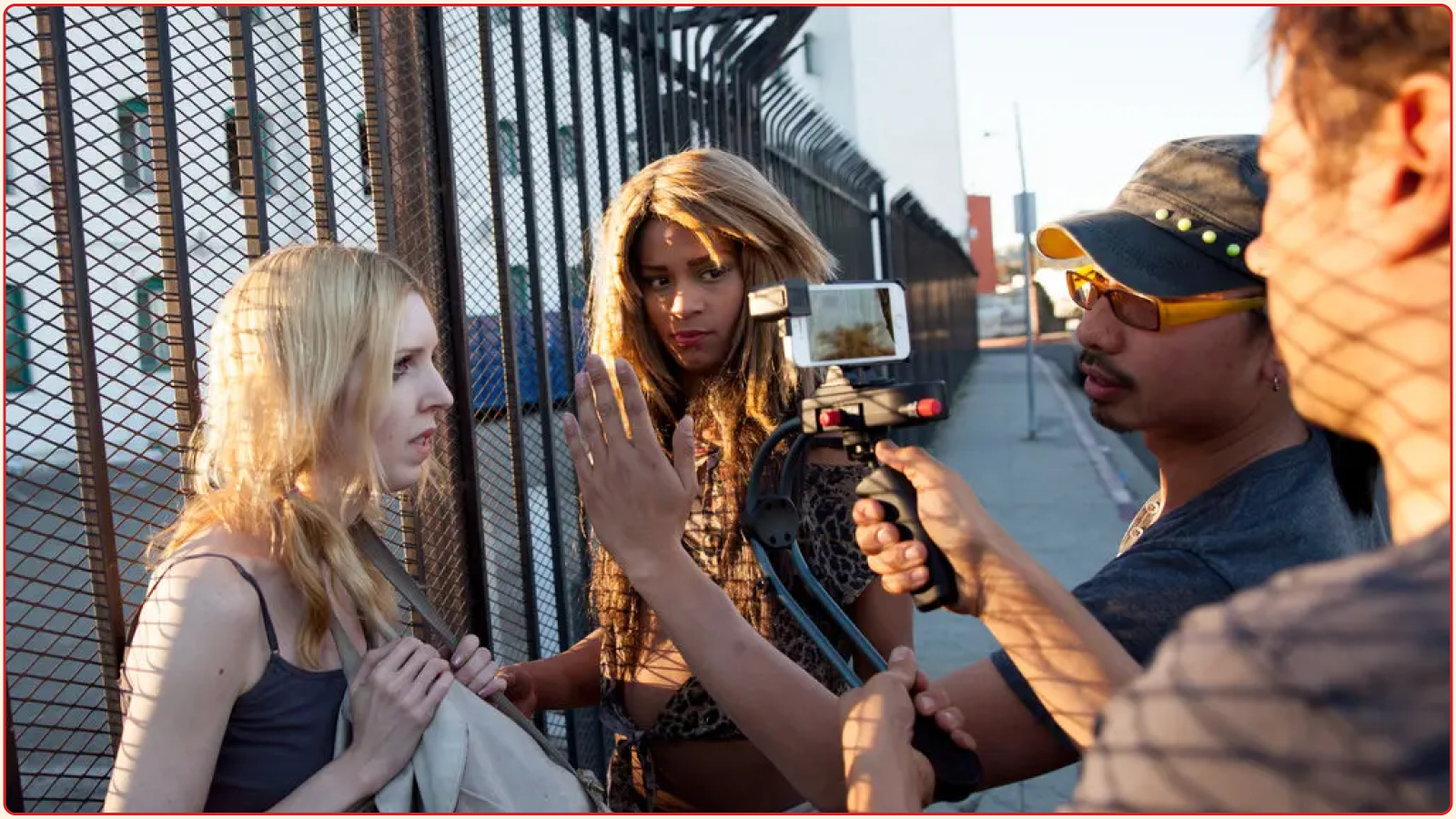

Sean Baker on the set of Tangerine (2015), photo by Shih-Ching Tsou

GJA: Your movies are often about very specific communities, and you make them in close collaboration with members from these communities. How have you been able to establish that trust?

SB: It’s much easier than people think, especially when you’re starting off. It’s really just about respect and about giving a lot of time. And if you’re not wanted, you walk away. But, for the most part, people want to tell their stories. Maybe because not a lot of people have the opportunity to. I’ve always found people who were open. I think they appreciate that I’m saying, “I want to tell a story in your world, but I don’t want to do it without your involvement.” I learned most of this on Prince of Broadway.

For Take Out it wasn’t such a conscious thing. We were living above a Chinese restaurant at the time, and because Shih-Ching knew Mandarin, she was able to converse with the delivery men who would spend their time in the stairwell. Our initial thought was to make a film about a delivery man and have him be a vehicle for us to see New York, seeing different cultures and different languages and different races at each apartment he’d go to. But then, when we started asking these men about their lives and realizing some of them had smuggling debts and some were undocumented, that started to become the story.

For Prince of Broadway, I was out on the street here in New York, in the Wholesale District, approaching men, saying like, “Tell me about your lives.” And they would think I was either a very annoying film student or police. Many of them were like, “Okay, I guess we’ll talk to you, but we don’t have much time. Talk to this dude Prince instead. He’ll want to talk to you.” When we finally found Prince [Prince Adu], and he said, “If you make me the lead of your film, I’m going to show you the world. I’m going to help you tell the”—I remember he said it exactly like this—“the authentic African New York experience. I will give you that and I will give you locations and help you find actors and everything.”

That’s really what taught me that it’s just about listening and involving and respecting people. I’ve taken that with every film, it’s grown, but it really started with Prince.

GJA: So was it a conscious decision with Take Out to make something that was less about the world you grew up in and knew, like Four Letter Words? Or was it just because you happened to be living above a restaurant?

SB: A combination. That definitely inspired it, the fact that we’d see these men everyday. But then, it was the Dogme 95 movement. I’d worked so hard in the ’90s to try just to gather $50,000 and shoot this first film of mine on 35mm and take years with the script and rehearsals. And suddenly, Dogme 95 came about: I fell in love with The Idiots (1998) and I was intrigued by the movement, [the idea that] all you have to do is pick up a mini DV camera and do this. We were like, “Let’s do it.”

GJA: You’re your own casting director, at least on the last two movies. How do you cast? How did you learn to cast?

SB: We’re always keeping our casting caps on. It can be from the street. It can be from Instagram. Instagram is amazing these days for casting. And in the past, it was Vine; that’s how I re-fell in love with Simon Rex [star of Red Rocket (2021)]. Or it can be movies. That’s how Mikey [Madison] came onto my radar. I had just seen Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) and was talking to people about her character. I thought she was amazing. I went back a third time to see that film, just for her scene.

And we discovered Suzie [Son, co-lead of Red Rocket] at the Arclight in Hollywood. We just came out of a movie and were in the lobby and she walked in. We saw her across the lobby, and the fact that this 5’1” little girl could immediately draw our attention; that is special.

GJA: So, that was back in 2019. Was Mikey always Anora?

SB: No, I was like, she’s special, let’s keep her filed in the back of my head. And then we saw Scream (2022). She showed such a range in those two performances.

GJA: What about Karren Karagulian, who has an incredible role in Anora as a lovable almost-villain. He has been in every one of your movies. How did you meet him?

SB: I edited a student film in which he was the lead. He was great. I gave him a minor role in Four Letter Words and we’ve kept in touch since. Over the years, our friendship has grown, and when I started working on Take Out, I knew I wanted to cast him. I just love him so much that I just keep on using him. Everybody talked about that moment where he argues with Ming Ding about the chicken-and-beef wrong delivery. He made such an impact with only 30 seconds of screen time and I said, “Next time out, we’re giving you a lead.”

I’ve always had full faith in him. And he has the connection to the Russian American community because he’s Armenian and his wife, Lana, is Russian; she plays his wife in the church scene. He was able to give me such insights [into the community]. He speaks Russian, so he knows all the vernacular and slang. I didn’t realize how much pressure I was putting on him with Anora by giving him a more comedic role and tons of dialogue to memorize. He’s told me since, but he certainly didn’t show it at the time.

Anora (2024)

GJA: I’ve read that you wrote a Brighton Beach-set movie a decade before you made Anora.

SB: Yeah, it’s a script that we never got produced. That’s another one of those fate things. After Prince of Broadway, I had an agent. I don’t have an agent anymore. I’m not into the agency thing. I learned my lesson. But they took this script of ours, and they were like, “Yeah, we’re going to make it. It’s going to be $15 to $20 million and we’re going to have Ryan Gosling and Tom Hardy play Russians.” I was like, “Whoa, wait a minute. First off, no. I don’t want that at all. That’s not the way I make movies. Plus, did you forget that I wrote this for Karren?” Of course, it didn’t happen. They couldn’t find the money. But I’m really glad they didn’t, because again, that would’ve sent me down a whole different route.

GJA: Anora’s the first movie you have the sole screenplay credit on since Four Letter Words, I think?

SB: Yeah, yeah.

GJA: Did it feel different?

SB: No, not really. I just felt like I had a handle on the whole story. I knew the beginning, middle, and end. I just thought I could go solo on this one, simple as that.

All of my past collaborators are wonderful people, and we all expressed that we wanted to eventually go solo, and we all have. I think that our past films have allowed us to do that. Chris [Bergoch, co-writer of Starlet (2012), Tangerine, The Florida Project, and Red Rocket] is writing screenplays right now. And Shih-Ching, we’re in post-production on her solo debut, Left-Handed Girl.

GJA: Oh, amazing.

SB: I’m editing it right now! She did a great job, and I’m really excited. It’s a film I co-wrote with her. It will feel like one of our films; it feels like it almost has aspects of The Florida Project, and it’s a family drama that takes place in the night markets of Taipei. And shot on the iPhone. But a current version, so it was shot in 4K. I wasn’t part of production, so it’s really kind of nice to be able to see what she did with her casting. It’s something we’ve been trying to do since Take Out, and these films allowed us to find financing for that. I’m really proud of her.

GJA: I wanted to ask about music in your movies, or your relationship with music Take Out and Prince are more or less following Dogme 95 rules [Rule #2 of the Dogme 95 “Vow of Chastity” reads: The sound must never be produced apart from the images or vice versa. (Music must not be used unless it occurs where the scene is being shot.)]. Nothing non-diegetic. And then the last two movies basically have anthems. These huge needle drops.

SB: Yeah, exactly. I’ve never had a composer for my films, because I’ve found these needle drops that become the score. Not that I don’t appreciate film scores—some of my favorite scores are really big scores, like Brian May’s Road Warrior (1981) soundtrack. I think that’s one of the best soundtracks ever. But for some reason or another, because ultimately my films are in that social realist realm, even if I get broad or explore other tones and genres, most of my music is diegetic music coming from a radio, coming from something. The only times I’ve deviated from that is when I take these needle drops and allow it to become a moment like “Bye Bye Bye” [in Red Rocket] with Simon [Rex] running through the backstreets of Texas City. Or, in this new film, the Take That song [“Greatest Day”] is meant to be almost a cliché anthem for a romantic comedy. It’s a big pop song. It’s an earworm. You can hum the tune after listening to it once. It’s on the nose. It’s talking about her greatest day. That was an intentional almost tongue and cheek thing that became non-diegetic.

GJA: Last question: is there a particular film you’d recommend to our audience?

SB: I’ve been talking lots about Nights of Cabiria (1957), but I realize that when I do, many people know it, but they haven’t actually seen it. It’s one of the Fellini films that people don’t really talk about as much, and they should. It was a big influence on Anora, because I feel it’s one of the early examples of a truly empathetic look at sex work. And it’s so moving.

Almost every scene in the film is on Giulietta Masina, just like I did with Mikey. And what’s kind of serendipitous is that we have an unintentional nod to Nights of Cabiria. In the last scene of Anora, I had just scripted it, “She cries.” I didn’t know how Mikey was going to perform this. And I don’t know if you remember, it’s just a single tear that we see drop off of her nose. I was like, “Oh my God, we just did a nod to the film that was one of the major inspirations for Anora.” Obviously, Mikey didn’t intend that, it just happened. But the connection is there.

Anora (2024)

Share: