Essay

Save the Man: Indigeneity in Pre-Code Hollywood

On Pre-Code Hollywood’s brief but fascinating run of titles centering Native America.

Share:

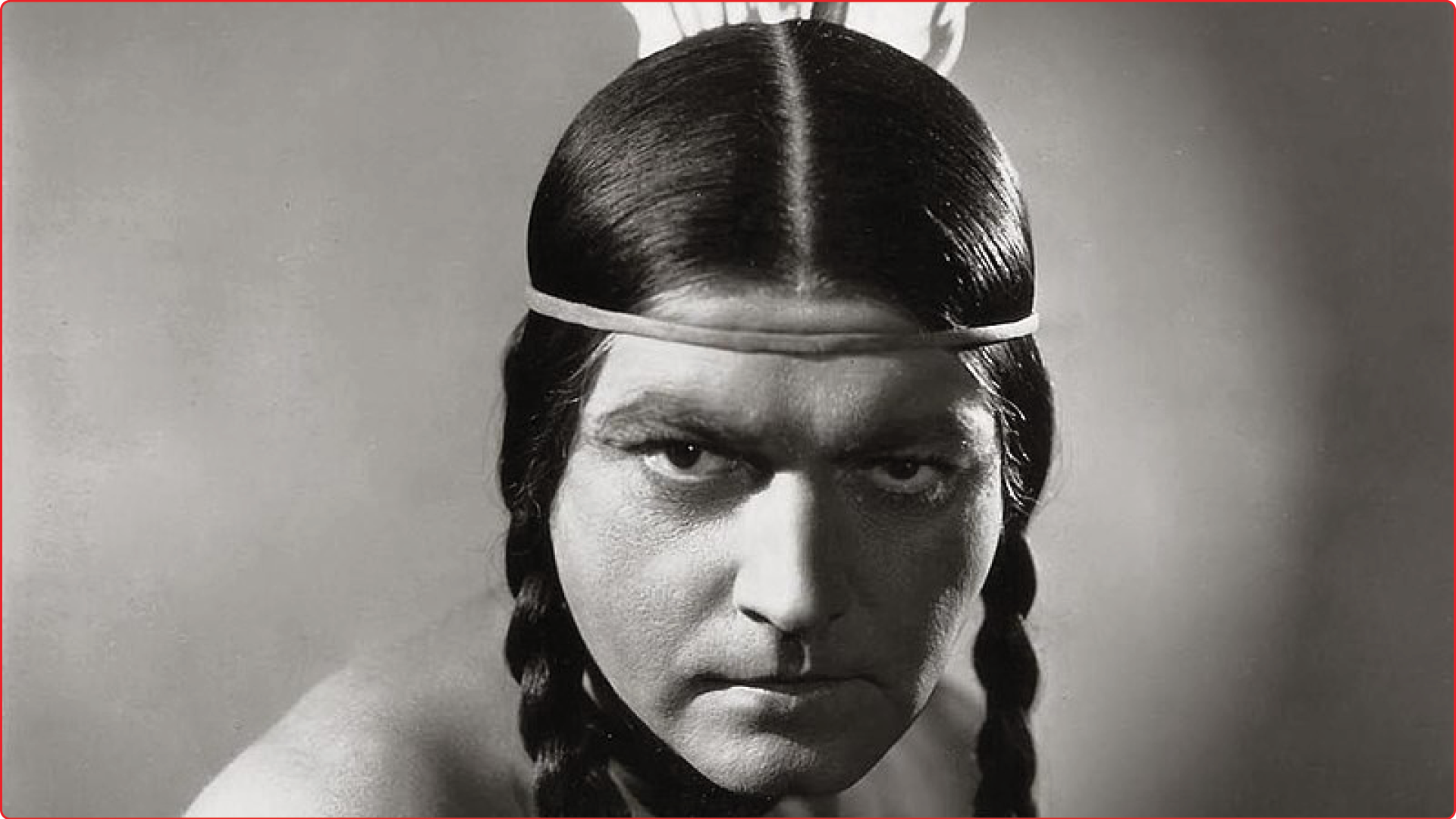

The Squaw Man (1931)

THERE’S A RUNNING JOKE IN Indian Country that every 20 years America remembers we exist. If you start counting backwards from this past decade with the resistance at Standing Rock, it actually tracks. These ripples of awareness in popular culture are usually instigated by activist pushback (the American Indian Movement in the 1970s), government policies (the Indian Relocation Act of 1956), or in most cases some combination of both. Dialing back a few more decades, we find the 1930s presented some unforeseen and complicated realities for Native America which then played out on American cinema screens; to best understand them, you have to look at the prior decade to see how the soup was made.

With the close of the Apache Wars in 1924, this country’s longest conflict on record, the centuries-spanning American Indian Wars were officially declared over. Ironically, that same year saw the Indian Citizenship Act signed into law, by which this land’s original people were granted the right to vote. This decade was also marked by the Osage Indian Murders, the 13-year-long murder spree of over 60 wealthy Osage tribal members that eventually led to the birth of the FBI, and the basis for Martin Scorsese’s upcoming Killers of the Flower Moon, adapting David Grann’s book. The chaos that sculpted Indigenous life in the 1920s took a welcome turn at the decade’s closing with the 1929 presidential election of Herbert Hoover. Many of Hoover’s policies presented a dramatic shift from those of centuries previous, and a move towards re-recognizing American Indian Nations as enduring political entities. It’s worth noting that much of this was influenced by his own Vice President: Charles Curtis, a citizen of the Kaw Nation and the highest-ranking Native American to have ever held office. This calm would be short-lived: in the fall of Hoover’s first year, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 landed like a sledgehammer. With the onset of the Great Depression, a period of uncertainty and dread heralded the incoming decade.

It’s of little surprise that Hollywood, which is forever reshaping itself to its audiences, found a way to infuse this psychic malaise into the churn of its product. The Depression put American film studios in dire straits, with many already still reeling from the financial implications brought on by the adoption of sound technology. Following the 1927 release of The Jazz Singer, the industry saw a 50% dip in audience numbers and the shuttering of nearly a third of the country’s theaters unable to adapt. Hollywood was willing to try anything to fill seats again.

Eskimo (1933)

These changes ushered in what is now known as the Pre-Code era, a period beginning in 1927 in which a slew of studio films regularly contained more risqué, violent, or profane themes onscreen, thanks in part to the loose enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code censorship guidelines, commonly referred to as the Hays Code, created by the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA). This epoch would come to a screeching halt on July 1, 1934, when studios finally gave way to the Code, in part due to the threat of boycotts by Catholic, Protestant, and women’s groups vowing to disrupt box office margins of films they deemed immoral, and the MPPDA’s creation of its Production Code Administration office and appointment of Joseph Breen, a noted Nazi sympathizer publicly critical of what he believed to be a Jewish-controlled industry, as its hard-lined, conservative overseer. Needless to say, the party was over.

This brief moment in film history reflected the disenchantment and fatalism of the Lost Generation of the 1920s and early 1930s who, after living through the horrors of WWI, were now facing the financial collapse of the very nation they fought for and lost friends in the defense of. Whether it was the increasing bleak outlooks and moral ambivalence permeating crime pictures, the ribald scenarios popping up in comedies and musicals, or the overt pleas for reform espoused in social problem films, the silver screen’s offerings at this time presented a reconfiguration of America toward something more honest in terms of how it saw itself, rather than something it traditionally aspired towards.

Within those genre frameworks, there existed a unique trend that confronted two of this nation’s foundational quandaries: the American Indian, and where he figured within the Great Experiment. By the 1930s, audiences had grown accustomed to seeing Indigenous people as staples in Westerns, a genre that quickly fell out of studio favor with the advent of sound. What made this moment singular within studio films was its contextualization of the Native American experience within a contemporaneous setting, in contrast to the Western’s antiquation of it. Suddenly there were films centered on Native characters, some of whom are even performed by Indigenous actors, as they navigate the prejudice they face on their own homelands. Often openly critical of White America, they present it as grotesque, corrupt, and cruel, in line with the charges of cultural hypocrisy put forth in other Pre-Code films.

That’s not to say that this subgenre was without thematic precedent. These films both tapped into, and at times challenged, older literary traditions and stereotypes, such as: the fantasy of Indigenous women needing to be civilized by white men in order to fully realize themselves, or mixed-race individuals tragically torn between two worlds. Despite these mixed intentions, many of these films embody a colonial paternalism rooted in the latter half of the infamous phrase “Kill the Indian, save the man,” coined by Richard Henry Pratt, the military officer turned superintendent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School whose aim was to forcibly assimilate Native Americans into white society. The country had given up the killing part (on paper, at least) and viewed its first people as something to logically dissolve into its citizenry.

The Squaw Man (1931)

A fascinating paradox that also manifests in this strain of Pre-Code films is its wide use of depictions of interracial relationships. While the Hays Code would not be fully flexed until 1934, it explicitly placed a prohibition on anything implying miscegenation, which it defined as “sex relationships between the white and black races.” Interracial unions in 1930 were still banned in 30 states and their cinematic depiction would infer the condoning of an illegal act. These statutes were widespread and unanimously targeted at African Americans and Asian Americans and their relations with whites. However, restrictions on white unions with Native Americans and Latinos were virtually nil as they had been fairly commonplace since the nation’s foundational periods and westward expansion. As such, this loophole was fully exploited by studios to openly discuss racism and its origins in America.

A perfect example of this can be seen in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Squaw Man in 1931, his third adaptation of the play (following versions, released under the same name, in 1914 and 1918). The narrative finds British aristocrat Jim Wingate (Warner Baxter) on the lam after taking the fall for his cousin’s embezzlement scheme. He flees to Montana under a pseudonym, taking over a ranch, and is rebirthed by the rugged landscape. In the local saloon, he witnesses a bootlegger attempting to assault Naturich (Lupe Vélez), a Native woman. He saves her, marries her, and a son follows soon after. Much of the drama is evoked from Naturich’s Indigeneity clashing with Jim’s rigid, white mores, and the disagreements they have over raising their child. She believes that he can learn her people’s way, whereas Jim sees no other option than sending his son to England to matriculate.

Other striking instances of this filmic trend are found throughout the filmography of W.S. Van Dyke. The director, affectionately nicknamed “One-Take Woody” by studio heads, was known for his efficiency and ability to work across genres, but his exotic adventure films of the early 1930s exemplify typical depictions of Indigeneity in this period. Eskimo, shot on location in then-Alaskan Territory in 1933 and the first feature in an Indigenous language, follows the day-to-day life of Mala (Iñupiaq actor Ray Mala) and his community. After the death of his wife at the hands of white fur traders, Mala enacts revenge and is forced to go on the run from authorities. A year later, Van Dyke would set his directorial sights on the Navajo Nation with Laughing Boy, starring Ramón Novarro as the eponymous Navajo silversmith selling his wares to crass American tourists and vying for the heart of Slim Girl (Vélez), a white-raised Native woman who many in the tribe believe to be a prostitute in the nearby town. A doomed love triangle forms between her, Laughing Boy, and her white former lover that exposes the racism in reservation border towns, Indian trading posts, and the tourism upon which they thrive.

Laughing Boy (1934)

One of the most emblematic works of this subgenre is Alan Crosland’s Massacre, released at the close of the Pre-Code era. The picture follows Chief Joe Thunder Horse (Richard Barthelmess), a cocky “Show Indian” who is the top draw in the Wild West Show he tours with. Whether it’s speeding his gaudy sports car, bedding white women, or demanding higher pay, Joe unapologetically lives life fast—until word reaches him from the reservation that his father is dying. He returns home to find his community in disarray and under the rule of a corrupt white government official. Pushed to the breaking point, he leads his tribe to revolt against their oppressors in an explosive, damning finale that puts the very foundations of America on trial.

That Massacre made it into theaters only six months before the Hays Code went into full effect feels like a miracle in and of itself, as it openly violated numerous rules on the list. It would be more than three decades before the industry finally abandoned the code, in 1968, but even today, Hollywood has yet to return to anything in terms of the consistency of its cinematic output of the Pre-Code era’s run of titles revolving around nuanced Indigenous characters—firmly within a contemporary setting—and treating their realities as something worthy of reflection. Pictures like Massacre are by no means perfect representations of Native Americans, with some components having aged worse than others, but they nevertheless remain fascinating relics of a time when the country split open, turned inward, looked a little deeper, and mulled over just where things went so wrong.

Massacre (1934)

Share: