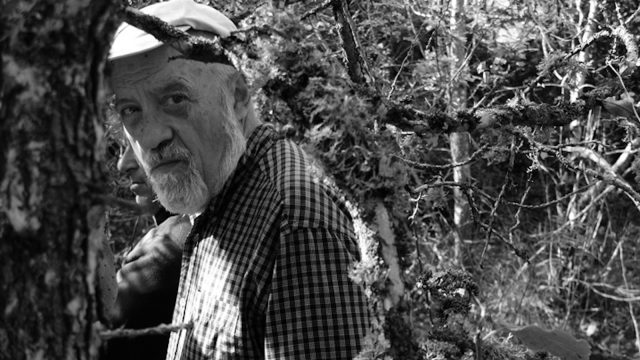

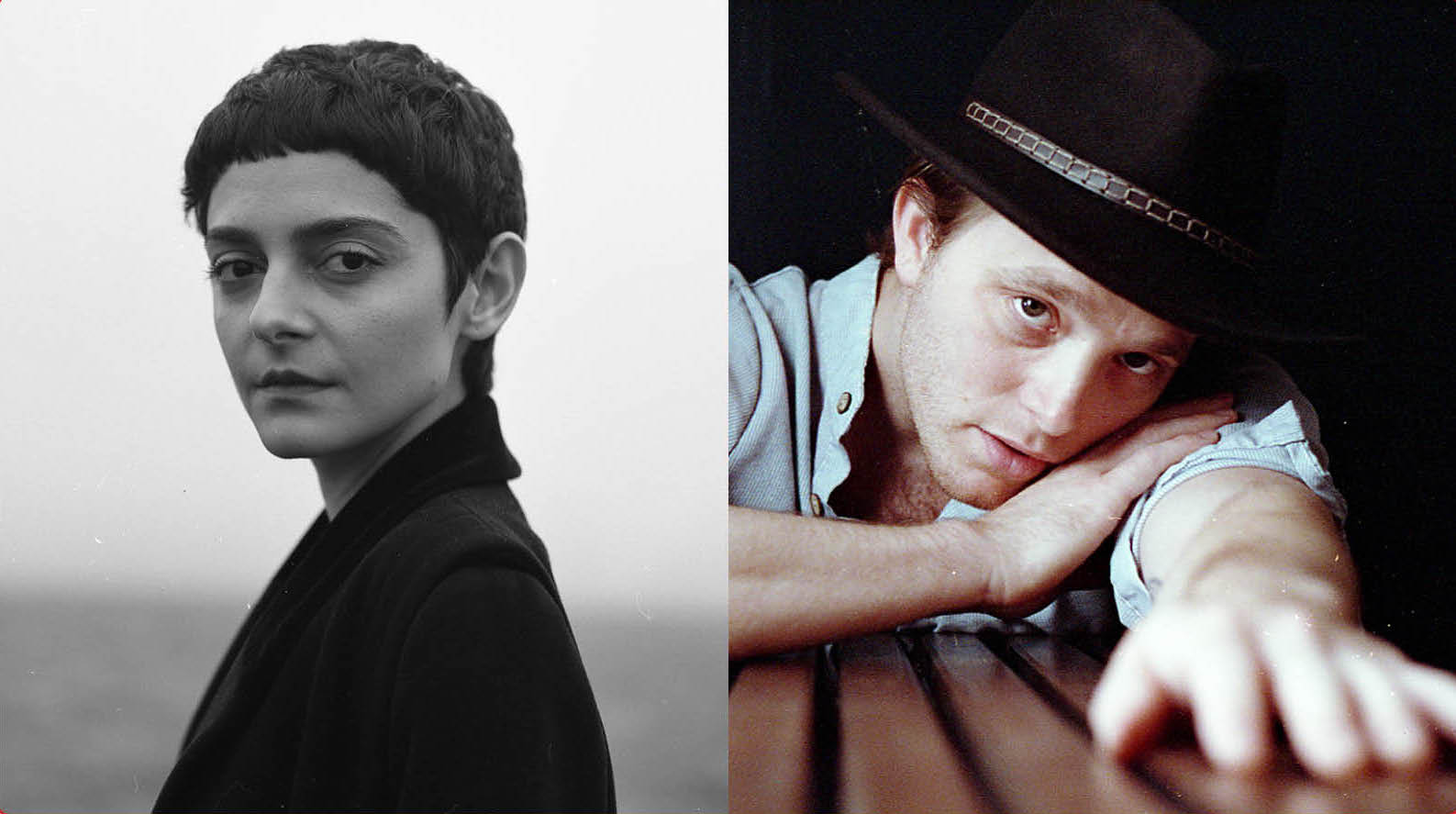

Interview

Ryan J. Sloan and Ariella Mastroianni

The first-time filmmakers break down their mind-bending debut.

Share:

Gazer, a new thriller co-written by Ryan J. Sloan, its director, and Ariella Mastroianni, its star, is a meditative head trip steeped in the hardboiled stylings of classic film noir and the intricate narrative structures of films like Memento (2000). This debut feature follows Frankie, a lonely single mother with Dyschronometria, a degenerative condition that twists her sense of time, as she works to solve a mystery she stumbles into outside a grief counseling meeting. Shot over several years on hazy 16mm, Gazer manages to be both dreamy and intricate, at once loose and propulsive, grounded in Frankie’s perspective by the analogue tapes she makes to keep herself from zoning out and “losing time.” Accompanied only by the looping playback of these probing self-reflections, Frankie struggles to keep her life on track in the face of terminal illness, a separation from her daughter, and a violent incident in her past that she can only access in her nightmares—all as a mysterious criminal case tinged with Cronenbergian corporate intrigue builds up around her.

Payton McCarty-Simas: So this is your first feature. What made you two want to become filmmakers and what was the first inspiration for Gazer?

Ryan J. Sloan: I’ve always wanted to be a director, but I started working as an electrician when I was about 13 and I got lost in that world. I met Ariella when she was about 14 years old at a friend’s play. She was acting already. We remained very close over the years and when COVID hit, she was stuck in a job, I was stuck in a job. And we were just like, “What are we doing with ourselves here?”

We’d been dreaming about making this happen, and Ariella and I were like, “Let’s write that script. Let’s sit down, let’s watch movies together, let’s figure out the kind of story that we want to tell.” We got lost in films like The Third Man (1949), Blow Up (1966), L’Avventura (1960), The Conversation (1974), Blow Out (1981), Vertigo (1958), Memento—lots of films that follow this story structure called “the spiral structure.”

Ariella Mastroianni: I had always been drawn to the arts when I was young, but I never really thought of it as necessarily something that I like, quote, wanted to do. It’s just a form of self expression that I’ve always had. During COVID we felt like we had a lot to say, and there are a lot of things about COVID that you can feel in the film, themes of isolation. It’s a very stoic film about being removed or separate from society, on the outside looking in. That’s how we were feeling. We were looking at the movies that have always spoken to us, that we would’ve risked it all to see in a movie theater and gotten COVID for. So Gazer, I think, was born from those feelings of isolation and wanting to bring back a kind of cinema that really excited us.

Gazer (2024)

RJS: But it was also born out of necessity. There was nobody that was knocking on our door saying, “Do you two want to do something in this industry?” There are gatekeepers, and it’s even more difficult when you aren’t able to afford film school, or you aren’t born into a family where everyone’s connected and everybody can help each other out and pull each other up. When you’re really on the outskirts, you have no choice but to make it yourself.

We knew it was going to take time and we knew that we couldn’t afford to do it all in once, so we mapped it out. We looked at what the Coens did with Blood Simple (1984), what Aronofsky did with Pi (1998), what Nolan did with Following (1998). Nolan shot on weekends for a year and we ended up shooting on weekends in April and November for two-and-a-half years, pretty much whenever we had the money and whenever we could afford the film, the processing, and the scanning. All of our dear friends that were a part of this project gave so much in return for a really good lunch. That was all we could offer people.

PM: That communal element really comes through watching the film. In another interview, Ryan, you mentioned that a lot of the locations that you used belong to people who you’d done electrical work for?

RJS: It was pretty wild. I would basically just be in somebody’s house and think, “This would be a great location for X, Y or Z,” and I’d go knock on their door after a day’s work and explain to them what was going to happen. And, you know, they were all very receptive, but a lot of them had no idea what they were getting themselves into, even if we were a small but mighty film team. There were only about six of us on the crew. Ariella and I were set-dec, we were lunch, we were everything. So, yeah, it was interesting, getting them involved.

My favorite thing, to be honest, though, was the businesses that we got involved with. My town [Kearny, NJ] is being gentrified like a lot of other places, and all these old factories that have so much history and all these old homes that were built in the early 1900s are being knocked down. They’re putting up these ugly fucking apartment buildings. We were able to shoot in a factory that was across the street from my shop that got knocked down after we were done shooting. So I was able to capture a little bit of history within the town, which meant a lot to me.

AM: I think that was the beautiful through line, how we worked together and also this sense of community that you felt from the film, which makes me so happy to hear. We didn’t owe anything to anybody. We weren’t after some sort of goal. We wanted to make a film that we wanted to see, that involved people whom we wanted to see it with, and I think all of our crew felt that way. Everything about it was genuine; that was our guiding force the whole time, you know?

Gazer (2024)

RJS: And we created a new genre—we have Jersey noir now.

PM: Let’s talk about Jersey noir. What is it about this community that speaks to noir as a genre?

RJS: Well, the genre of noir is specifically American, right? It’s the people on the outskirts of society that are struggling to get by, and they’ll get by by any means necessary. And what’s interesting about my town is we’re literally in the shadow of New York City. There’s a lot of gritty crime underbelly stuff happening here: Jimmy Hoffa was from around here, there’s a lot of Mafia related things. The Sopranos (1999-2007) was shot in Kearny–my in my fucking town!

One thing I wanted to say too is that Metrograph called me a “New York writer-director,” and that is not true; I have to just state that real quick, because I very, very purposely did not point the camera toward New York City once. I love New York City, but I am not from New York City. I am not a New York City person.

AM: He waves the Jersey flag very high.

PM: For Metrograph, you specifically highlighted a couple of films about audio-surveillance with Blow Out and The Conversation. But within this film, while there are definitely scenes where Frankie is overhearing and discovering things through auditory surveillance, it’s more introspective than that. It’s more about Frankie’s internal monologue and how she’s processing herself and the way she looks at the world. It’s kind of a reversal of that trope. How did you come to that idea for Gazer and how would you put that in conversation with these other films?

RJS: I remember specifically thinking, “If I can make any movie, it would be something along the lines of Coppola’s The Conversation.” I loved how it’s a character study buried in a genre film, and how it captures loneliness in such a beautiful way. That’s another thing with Blow Up, The Conversation, and Blow Out. We see the whole film through one character’s eyes. These characters are witnessing something—an incident—and then trying to understand what they saw. And every time they dig deeper, they uncover a little bit more, but it’s murky waters, so they don’t fully know what they’re uncovering until it’s too late and it’s already upon them.

I love that idea so much because I think that’s how we live life. We’re always trying to understand what’s going on in the world and where our place is, but by the time we figure it out, it’s too late. We’re dead. I think about Paul Newman. In his final days, he made a comment that he thought he finally understood what it meant to be an actor. I love that. That’s how long it takes.

Gazer (2024)

AM: It’s Frankie’s using the tapes that allows us to get into her mind. The whole thing is from Frankie’s perspective and understanding her loneliness and how she interprets it, it’s how the audience gets on board with her involvement in the mystery: she is such a lonely person, such a curious person—her curiosity is fed by her loneliness. “What happens when you live such a lonely, ghost-like existence, and somebody sees you?” Frankie’s yearning for normalcy and connection, her yearning for being seen, really fuels her. Another big inspiration for us was this kind of Schraderean character.

RJS: [In Paul Schrader’s films] they’re all male protagonists. It’s “God’s lonely man,” but who is “God’s lonely woman,” you know? I think having Ariella as a co-writer and obviously the lead of the film was so crucial and and so important because you don’t want any more of the male gaze on that.

AM: We discussed a lot about Frankie existing in this space where she is both masculine and feminine. She is a single mother; she’s filling in both roles. We wanted her to exist in that space where she is taking on all roles, existing everywhere and nowhere. I feel like this is where Frankie kind of fits, both narratively and as a character.

RJS: And then you have the noir genre. We have narration, shadows, unreliable narrators, voiceovers, all those things, right? We tried to pay homage to those tropes and twist them a little bit where we could to make them as original as possible. There was a lot of exploration, trying to map out where everyone was at a given circumstance—kind of like Frankie, as you mentioned, being a time traveler. I love that. I’ve never thought of that before, but it’s true. Where does she go in between that time? And that leads us to these Lynchian nightmare sequences.

PM: Absolutely, and I wanted to get into those dream sequences next. As I was watching Gazer, I was struck by the really strong presence of Cronenberg. Were those references to eXistenZ (1999) and Videodrome (1983) in those unexpected body horror sequences?

RJS: Yes, definitely. When we were originally writing, we were actually writing flashbacks. And there was a point where one of us turned to each other and was like, “Man, this is a fuckin’ nightmare, this is really sad.” So I think Ariella was like, “Well, let’s explore it as a nightmare. Let’s see what happens,” and we had a lot of fun with it. There was a version where all the furniture was upside down on the ceiling, but I couldn’t build it in time. It just felt like a really fun way to explore this haunted past, this thing that won’t let Frankie move on. That’s some of my favorite stuff in the film.

AM: I just love those sequences. I feel like they’re the most expressive of the film, the core of the film. Because what had happened between her and her husband shapes her every decision, it felt only right that if it feels like a nightmare to Frankie, that visual of her internal hell should feel like a nightmare to the audience.

But [as for] approaching it with some of the body stuff, there’s nothing more physical than giving birth and dying. Frankie is a mother and she lost her husband, so it felt only right that we presented this idea of birth, life, and death through the body. She is so stoic and so removed from humanity, but everything about her journey comes down to the body and physicality.

Gazer (2024)

Share: