Interview

Pedro Costa Remembers António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro

An interview with the Portuguese filmmaker on his teacher and heroes António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro.

Share:

At the close of Trás-os-Montes (1976), the first feature by António Reis and Margarida Cordeiro, we see a train wend its way across the plains of this remote northern province of Portugal, the namesake of the film. The train displaces the men and women of this land who are seeking wage work in Porto or Lisbon, leaving behind a home depopulated but for children and the elderly—and ghosts and myths. The time is twilight, the camera is positioned at a distance, and there’s hardly enough light for an exposure: all we can make out is the plume of smoke moving away, picked up in the dwindling rays of the sun. As the shot endures, this concrete event becomes more abstract. It shakes free from the earth, even as it burrows deeper into it, and becomes a memory, a dream, right before our eyes.

It was a sight Reis and Cordeiro had observed many times over the years, on countless nights, long before they filmed it. Then one evening in 1974, on a trek thousands of kilometers throughout the north, they shot it in just one take. Such wild dialectics are what nourish and invigorate the films of Reis and Cordeiro: this mingling of deep time and brute speed, of macro and micro scales, fact and fantasy, rigor and intuition, all brought down to bear on each shot. The image of this train would leave a permanent mark on Costa, who first saw Trás-os-Montes while he was a student at the nationalized film school in Lisbon in the late 1970s, where Reis was his teacher. Reis would become the single most important influence for Costa in these formative years; the work that Reis made with his partner Cordeiro “opened a lot of doors and windows” for the young filmmaker. In our conversation, Costa discusses his memories of Reis, a man who “lived every second of his life in love,” and how he still dreams of resurrecting Reis and Cordeiro’s way of working, their courage “to wait for the stars or the planets to be where they should be.”

EDWARD MCCARRY: You were António Reis’s student at the Film School in Lisbon. What kind of a teacher was he?

PEDRO COSTA: Well, [typically] there’s the person and the teacher. I say this because, with António, there was no difference. Sometimes you have teachers that are one way and then, in private, they’re different. António was not like that. He was always the same. When I arrived at film school, I didn’t know who he was. He had done Jaime (1974) and Trás-os-Montes, and I think he was preparing Ana (1982). But for me, he was unknown. I didn’t know much of Portuguese cinema; I was more into music at that time, and into politics. Cinema came gradually, slowly. I was finishing my history studies, but I was not happy with the prospect of being a history teacher. My friend and I saw an ad to apply to this film school, so we went. We each had an interview and got accepted. The school began, if I’m not mistaken, in 1977, just after our revolution. The cooperative teacher/student relationship, that was still in practice; the students had some power, and the teachers themselves were very much in that revolutionary movement. They were all very left-wing.

By chance, I lived close to António, in the same neighborhood in Lisbon, within walking distance from the school. After two or three hours of talking in class, we would leave the school and walk the streets of the neighborhood, and he would continue what he was saying. We would go to the park, or go get dinner, and we did this often. This was already a very different way of living for me.

As you might have heard or seen from the three or four photographs that exist of him, he was a very small guy, very nervous—nervous in the sense of tension, tightness. Something about him reminded me of Iggy Pop. [Laughs.] He was always tense, and he had a kind of sway. He walked as if dancing a little bit. At least in my memory, he always dressed exactly the same: little cap, leather jacket, brown pants. He was somewhere between a peasant and a guy in a rock band. He was not the usual teacher that I knew from my studies.

António talked. He loved talking, like Godard. He was equipped to talk. I mean, one could see that life prepared him to be a great talker, someone who could pass things on. He was a man of great studies. He studied history, art history, film, of course, and many other things. He was a poet, as you know. He could talk about writers and about any period in history. He was very captivating… And that’s how I came to this film world in Lisbon. He was the reason I stayed in film school. There were other people, two or three more. But António stood apart. Later, there was Paulo Rocha—but António was different. Then my friends and I saw Trás-os-Montes in the cinema, and that changed a lot for me. His aura as a teacher grew immensely. Everything was confirmed. Still to this day, it was the first Portuguese film that gave me some clues. Before then, I couldn’t figure out how to make films and shoot personal things, but Trás-os-Montes opened a lot of doors and windows, in every sense.

Then we became friends outside of school, because I quit school and started working as a production assistant on things that offered some money. At the same time, I was preparing my first feature and trying to get money for it. And I stayed in touch with António. I visited him and Margarida at their home often. We had a mutual friend, a filmmaker, João Botelho. He was a good friend of António. So we were together a lot. João’s second film was a remake of Tokyo Story (1953) in Lisbon [Um Adeus Português, 1985]. It’s a great film, and a bit forgotten now. I was an assistant director on it, and António is an actor in the film. Manoel de Oliveira is in the film, too, playing a priest. [Laughs.] António plays a peasant, with a pitchfork or something.

By chance, António was on the selection committee when I submitted my first film to the Portuguese film fund. He was one of five jury members. In the end, there were four votes against the film and only one for: it was António. I remember having a very sad coffee with António after. “I did everything I could,” he said. He was almost crying.

Rosa de Areia (1989)

EC: And he never saw your film, right?

PC: No. It was exactly when I finished the film that he died. When I was in the final mixing or something. A very strange death, a mysterious death. Completely unexpected… As I told you, he was a man of great sensitivity. He managed—maybe it was a curse, I don’t know—to always be in a kind of altered state. He was a poet. He was really the poet, if you think of Rimbaud or guys that are a bit… not crazy, no, not exactly. He was always in a state of…

EC: Agitation?

PC: Not in that sense. He was amazed all the time, in a loving state. A perpetual amorous state. It’s a state you have to be in when you’re shooting a film. I say this all the time now. Just in that moment. I’m not saying you can fake it for seven or eight weeks, but you should try to be there, you should try to be in love. But to live every second of your life in love, that’s difficult, maybe even impossible. But that’s what António did.

EC: You feel it in the films. Reis was erudite, and Cordeiro, too. He brought all this knowledge and research to the films. Yet when it comes to the moment of shooting, there’s a sense he’s leaning on intuition, and something new and unexpected is coming through. Clearly this is someone hypnotized in love—in love with what’s in front of him. All this rigor suddenly comes up against an intuition.

PC: Well, he really saw. He saw paintings; he saw films; he read. He had that with him all the time. Margarida, too, of course. I never assisted them during shooting; I was only just beginning as an assistant director. But all of us knew that shooting with António would be a dream, because there were stories from the guys who were there, especially on Trás-os-Montes—which was a difficult film, shot at different times, in different seasons—who talk about this perpetual state of invention. Meanwhile, I was in this professional world of assistant directing where you have to plan everything and do schedules. These guys said it was impossible to do this with António and Margarida. You could not predict anything. There’s the famous story about the eclipse in Ana. Or the train at the end of Trás-os-Montes. The train was a scene they had in mind, but of course, it’s something that you cannot write, cannot even imagine, cannot prepare. The story goes that the both of them, wrapped in blankets, watched that line of smoke going across the plains for months, maybe years, before making the film. And they shot it just once, in one day. But they had seen it a million times.

I still fantasize about this way of production. It was not impossible at that time, and [these days] it can still be put into practice: a bunch of people with a common, solid purpose who go make a film—something like this can still exist. But having the courage to wait for an eclipse, to wait for the stars or the planets to be where they should be… At that time, António and Margarida were the ones who pushed it further. And that came with accusations of absolute megalomania, of fantasy, of abstraction. You know, people said they were not very concrete or realistic people.

Jaime (1974)

EC: That’s one of the contradictions of their films, I think. On the one hand, the films are embedded in a very particular place, a people, a time. And yet they’re never satisfied with just filming these surfaces. Instead they try to get at… I don’t know, you could call it a poetic reality. They’re creating something new. They do this through “falsification” or “fantasy”—and hard work, of course. In an interview on Jaime, Reis talked about how he directed the patients of the sanitarium with the same rigor one would with professional actors, so that they became “both more human and more like sculptures.” As in, by giving something a form you’re making it both more eternal and more real. We see this in your films, too, this work.

PC: Yes. There is something there, in work itself, for any serious filmmaker. They approached every film with all the care of real work. António said when he got to those villages up north [Ed. Trás-os-Montes was filmed entirely in the remote northern villages of Bragança and Miranda do Douro with the villagers as actors and collaborators] that the people would have to understand this: that film is work. It’s not bourgeois activity. It’s not some circus thing. They had to make this proposal solid to the people they worked with. And the only way to do that was to show that it’s real work. Even to the point that some of them will suffer, in the sense that they will experience film as work, something as difficult as growing potatoes.

I mean, all the talk about documentary and fiction was immediately out the window when we were in class. The school had just three or four 16mm prints: Strike (1925); Stromboli (1950); Pierrot le fou (1965), and something else. We would watch the films a few times, write about them, and António would talk about them.

EC: It’s funny you mention Pierrot le fou. Joaquim Pinto, who recorded the sound for Ana, worked on the sound mix with Antoine Bonfanti, who did the sound for Pierrot le fou and many French New Wave films. You could say Ana is doing something similar to Godard in terms of sound and image, the dialectic between them. Reis and Cordeiro were something like outsiders, but they did have some relationships with other filmmakers, people like Jacques Rivette and the Straubs, who knew and admired their films. Do you remember any conversations you had with the Straubs about their films?

PC: I think they met two or three times. I don’t know which films they saw; Trás-os-Montes, for sure. Ana, maybe. They were very fond of António. And I remember I had this brief correspondence with Rivette, just some postcards, and in one he asked about them: “If you see António and Margarida, send them my admiration.” António was very proud of Rivette’s love for their films, Trás-os-Montes especially.

You know, I think their biggest admirer was Jean Rouch. They were very close. He was one of the first to recognize them, and vice versa. Among contemporary filmmakers, it was Rouch, Marguerite Duras, and Rivette who admired them the most, I would say. Duras came to class a lot… But António’s admiration for Rouch was immense. It was a very warm, fraternal thing between them. He was very close in sensitivity and temperament to António. The work Rouch did, as an ethnologist, was very close to the field work António did, collecting oral traditions, music, poetry.

EC: Right. I think that’s why Paulo Rocha wanted to work with Reis on the dialogue for Change of Life (1966). Reis had worked among the fishermen in the film, and he knew their language well.

PC: Exactly. He was from the north. He had done a lot of research alone. There are some fantastic photos of António on a donkey.

EC: Oh, yes, incredible photos. When Reis was doing this kind of research, this was before he was making films? What was the original aim of field work like that?

PC: This was long before any film. Although, from what I know, he had done some early film activities with the Cineclube do Porto.

Ana (1982)

EC: Yeah, we’re going to screen the film that he made with the Cineclube, O Auto da Floripes (1963). It’s a collective film documenting a piece of folk theater. I think Oliveira saw Auto and decided to make Rite of Spring (1963), which is almost a remake. Then Reis worked as assistant director on Rite of Spring, but he seemed to have an ambivalent relationship with the film. He had some misgivings about the text, as far as I understand.

PC: Yeah, it began with, let’s say, some remarks that he had about the way Oliveira was treating the text, then it evolved to the way he was staging or rehearsing with the actors. That led to a broader difference between them, even if, from Oliveira’s point of view, the admiration was immense for António. António was more reserved. There was a struggle there, theoretical and practical.

We could say António and Margarida belong to a fragile part of cinema, one that has existed through the ages. And I hope it will never end. But you cannot define this small village where António lived, and where maybe Jean Rouch lived. But Rouch was more equipped than António and Margarida to face the monsters of cinema: the money, the production, the difficulties, the real difficulties, and then the criticism. I mean, it was tough for António to hear some things, to read some things. It troubled him a lot, the lack of solidarity between people. He wanted something else, like me and like many people do, which unfortunately is completely ruined. In private, I often saw him on the verge of tears. He was sentimental. He was always à flor da pele, as João César Monteiro would say. Always this heaviness, this suffering. A little bit like Danièle and Jean-Marie. Those two were very open to the problems of the world. Everything entered them. And it is very difficult to live like that.

I think it was a good thing for him to be a teacher, because he was loved by his students. Most of the students were prepared to go anywhere for his films, to help him in every way possible. He was our hero. And it was obvious that he fed on that love. At the same time, he suffered a lot from not being recognized by institutions, by the powers that be, by critics, by financing. But that’s the difficult and dirty part of making films. It’s strange, because he was really a peasant, and a strong one. He was like an oak tree. But at the same time, he had this fragility that I’ve never since seen in a man.

O Auto da Floripes (1963)

EC: I can well imagine the power Reis had with young people. He made films that are, all at once, the most ancient and the most avant-garde—avant-garde because they’re so ancient. Organizing this program, I can tell you these are still young people’s films. All the energy is with them. They’ve been difficult to see for so long, and there’s a certain legend surrounding them, thanks in large part to you. These films still have a lot of power.

PC: He was always in school saying things like, “A shot, for you, must be a matter of life and death. If not, then it’s nothing.” So of course that connected completely with our youth, our temperaments. We were there to provoke and to question. And his principles were very radical. The work that we did with him was mostly oral. We were in constant debate, a permanent conversation, from which he concluded a lot about us… I remember exchanges with him where he would say—not so much with words—that you must stay on that rage, that blindness. Because, in fact, he was the same. He was really angry, revolting against something. He was a bit blind, of course, but that’s necessary. That’s what he would say: it’s necessary for you to feel this rage right now, maybe forever. Stay like that. It’s very useful for this work.

But again, in general, he was a very extroverted person, a happy man with a big smile. He was open to people. I think he saw that I was one of the guys who was going to persist. There were maybe five of us who really stayed and made films from those years. Like I said, I was an assistant to this guy João Botelho, and later with Monteiro, and, well, I found work that seemed interesting to me. And one day, just after school, I was working on the terrace of the cafe—which, by the way, is in that park you see in Monteiro’s films. António and Margarida’s house was in the back of the garden there, too. They lived there until his death, then Margarida stayed. It was only much later that she went up north.

EC: She lives very remotely, right?

PC: Where she was born, I think. I heard she’s not well at all. She’s old. But I was there in the park one day, probably between films or something, and António sat down and told me about a project. He said, “You have to help me with this one. You’re an assistant now, so you know how to do things.” And he needed a lot of things, like props and effects. I started reading it; it was not a script or anything like that, just notes. It was a science fiction project set in Lisbon, in black and white. And it had people from other planets—you know, creatures, entities. It needed a lot of effects. [Laughs.] Today, I don’t know how to judge it. But at that moment, it seemed super interesting. But then it didn’t happen. I can’t remember why. I think it was called December, but I can’t confirm… And that went parallel with a more famous project they were working on, a film in Mexico, which Margarida wanted to do alone after António died. It was Pedro Páramo. Maybe you know it.

EC: Yeah. It’s a shame, because Margarida was trying to do it alone for so long.

PC: Yeah, and well, this verified much of António’s anger and frustration after his death, when Margarida tried repeatedly to get funding and was turned down. And she suffered. Then she abandoned the project. I don’t think she ever forgave anybody. She never forgot. And that was very present with António, too. “I give myself to you completely, so you should not betray anything. Not me, not cinema, not poetry.” That was very present in him. It was not exactly about treason; it was about distraction. He didn’t like that. You shouldn’t be distracted. That’s how they’ll catch you. Bad things will get you if you look the other way. You must never betray your project, your dream, your team, your crew, your pal. But it’s true, Margarida suffered a lot.

Painéis do Porto (1963)

EC: Reading Juan Rulfo’s novel Pedro Páramo, you can imagine the film they would have made from it, with all these disembodied voices.

PC: It was a text made for António and Margarida.

EC: It really is.

PC: But the other one, the black-and-white science fiction project in Lisbon, that was their own text, their own invention. It existed in an almost poetic form. But then I think they shifted and thought they could get solid financing for Pedro Páramo. It was very exciting. They were almost ready to go to Mexico to do preparation. Location scouting. The ghost of Eisenstein was there, of course. A very deep ghost for António. For me, too, forever. For all of us. It was a very developed project, Pedro Páramo. I remember seeing books of collages, things that they gathered for research. It was going to be their next project, without a doubt, if they managed to get the money.

EC: It’s amazing to imagine them in Mexico. António was someone who rarely left Portugal. He was a regional artist, very grounded. But of course, their films have Kafka, Chinese poetry, Rilke, etc. So they brought all these far-flung texts and influences to their films. But it’s even hard to imagine them shooting a film in Lisbon, in a city.

PC: But they would have found a method. Like the Straubs did, who made films not only in Germany, France, Italy, but also in Egypt.

EC: I want to ask about António Reis the poet. I’ve read a few of his poems in English. And I know Reis and Paulo Rocha worked together on a book of haikus in translation. I don’t know if he ever said anything like this to you, but I recall Reis saying somewhere that he only believed in short books. He didn’t believe in big tomes. That’s why he was drawn to haiku, because it condenses more than an epic poem ever could, using very simple language.

PC: Yes. Although I wouldn’t say he was as dogmatic as that. But it’s true. He loved Oriental art, Japanese art, Chinese art. I remember him talking a lot about Persian carpets, and he knew a lot: the different schools, manufacturers, epochs, and styles. One of the filmmakers that he talked most about was Mizoguchi. And that was probably influenced by Rocha, because Paulo was in Japan for years, he spoke Japanese. They must have shared that love for Japanese cinema. So it’s not surprising what you say. It’s the simple idea of reduction. That a shot must concentrate vision. Of course, it always has to do with the limitations of material production. Not everything is permitted, not everything is doable in film. But that’s okay. Straub and Reis shared this concern for the material and the immaterial, both sides of the equation: to be very concrete and material, it’s the only way to get to the mystical.

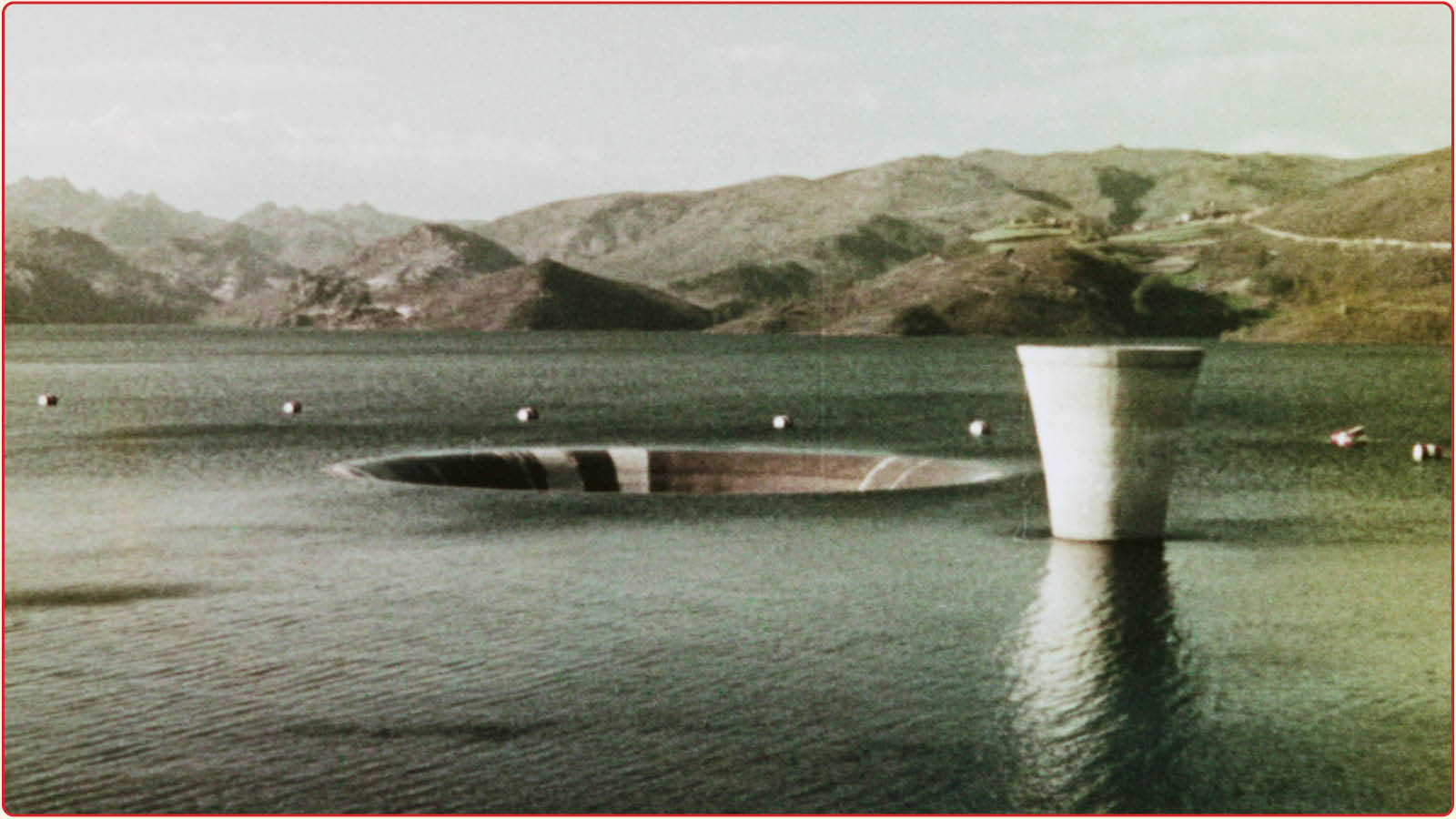

Trás-os-Montes (1976)

EC: Like the wisp of smoke from the train at the end of Trás-os-Montes. It’s a concrete image, and it’s also absolutely mystical.

PC: And you can relate that to the atomic form of the haiku, or to calligraphy. The brush that can paint the world in one stroke. That was their ideal. And it has a lot to do with film, with the obscenity of money, of people, the things you have to do to get a film crew somewhere. Then this void, this nothing that you film. You conjure all these things—cars, food, clothing, money, people—all of this to film an absence. And that’s what they did—Reis, Straub, Mizoguchi.

In the case of Reis, with the train, with reality mixing in that way, the confusion of time and space—that comes a lot from the study of Japanese painting. The Japanese painters, Utamaro, etc., I remember he taught them in his classes. Straub studied it, too. I remember one afternoon with Straub… I was amazed. He talked about a Japanese picture, I think it was by Utamaro; he had a reproduction in his house. He talked and talked about that picture, for maybe 20 minutes, with a little baby whiskey. He related it to some shot from a film, and he talked about the gradations of gray and all the mists that Utamaro was able to paint with just black and white and everything in between. But he said that in cinema we can’t do that because of all the bullshit of film and cameras and lenses. Straub and Reis shared this feeling: that film is a nuisance. What they really wanted to do is something without the camera, like painting or theater. The machine is a nuisance.

EC: Jean Renoir was the same. The camera was a complete nuisance for him. And all these “advances” in technology.

PC: Absolutely. That was the big problem for people like Straub and Reis: the camera. This stupid, cold object. And everything that comes with it: the mechanics, the politics, the economics. António was one of these guys who was not made for this world. [Laughs.] But it’s a shame. I sometimes think about the films António and Margarida would be making now. I wonder… It’s true, as you said, that he had the avant-garde on one shoulder and on the other he had, you know, Persia, Japan, and Velasquez, etc. I wonder what he would do with all the difficulties today, money-wise, and with the struggle of getting people to collaborate with you. Given this situation, I wonder if António would not be doing something very small, you know, with video or digital, more or less alone.

EC: I wish he had seen In Vanda’s Room (2000).

PC: Yeah, there’s obvious affinities.

EC: In my mind, he’d be doing something like that. That would be his solution, given the circumstances we’re dealing with.

PC: Yeah, surely. He would take the bull by the horns: “I can do it like this. Let’s not fantasize.” Or maybe Pedro Páramo would have been an enormous commercial success. [Laughs.]

EC: Perhaps.

PC: No, no, I doubt it.

Do Céu ao Rio (1964)

Share: