Essay

Pauline at the Beach

On Éric Rohmer’s summertime parable of maturity and lust.

Share:

The summer season is almost over. The brief tinge of gold is fading from France’s northern coast, the light is shifting back to watery gray. Most of the tourists have been pulled back inland; the beaches are spare and open. In the first shot of Éric Rohmer’s Pauline at the Beach (1983), the wooden gates to a summer beach home swing open. In the closing shot, they swing shut again. Within that perfect symmetry: a parenthetical final breath of summer.

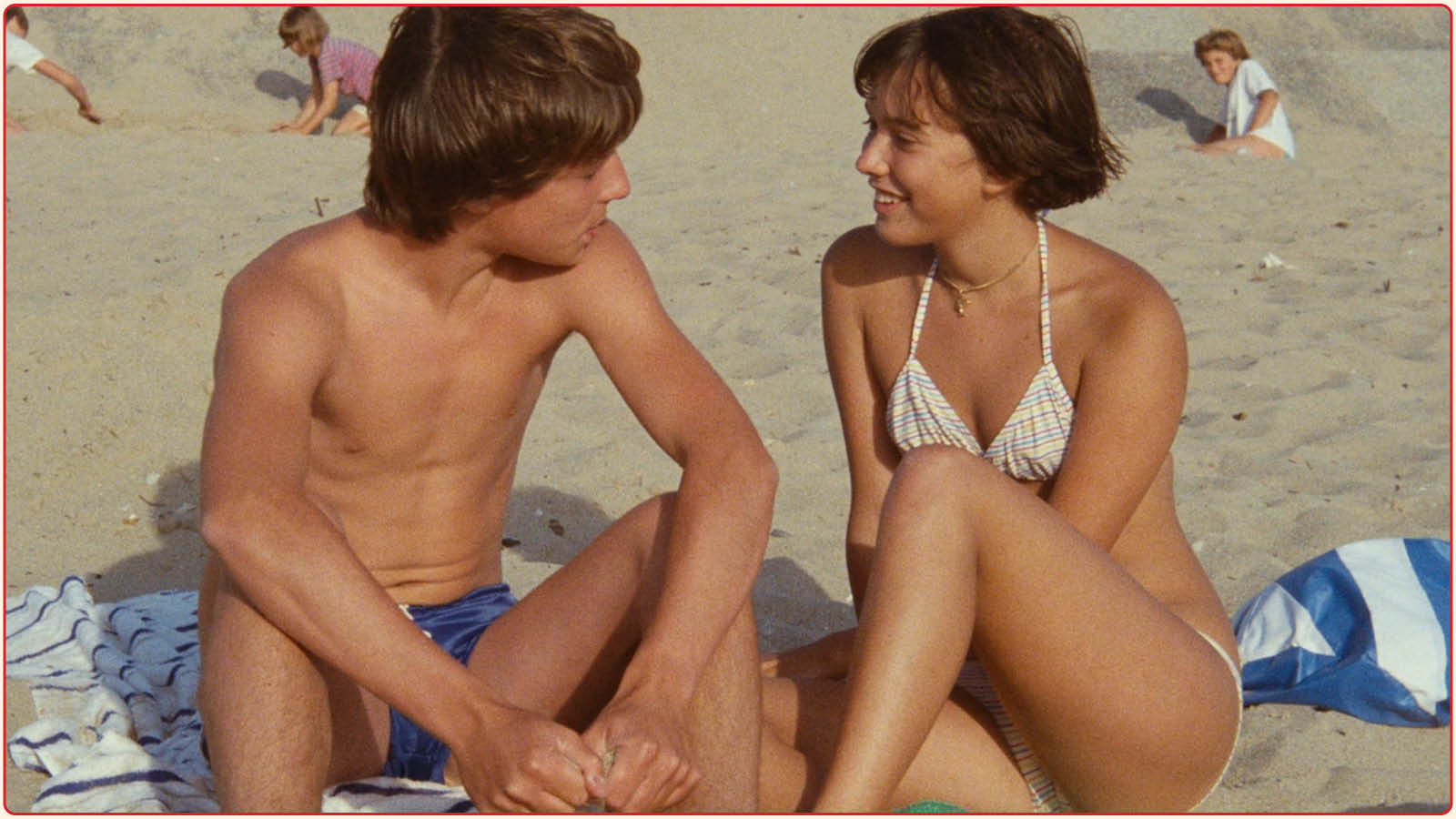

Marion, played by 30-year-old Arielle Dombasle, has been put in charge of her young cousin. They make an odd pair. Marion has a Barbie doll’s physique—she spends much of the film running across the beach barefoot on her tiptoes. Her ethereal blond hair and high cheekbones are almost cartoonish in their ideal and she knows exactly how beautiful she is. “Men may have killed themselves over me!” she exclaims. Pauline, played by the 15-year-old Amanda Langlet, is the opposite in every way. Teetering on the cusp of puberty, she has the deep tan of a child who’s spent months playing outdoors. Her hair is cut in a genderless page boy, her tiny slip of a bathing suit bottom falls off her ass in a manner as guileless as it is provocative. She gazes at her older cousin with clear admiration yet no jealousy.

Pauline at the Beach (1983)

Marion announces that she’s glad the neighbors are gone, that the house is without a phone, that they will finally have some quiet. She grills a very reticent Pauline about whether she’s ever been in love (she hasn’t, not really). Then the two head to the beach, where Marion instantly stirs up a dramatic tortured love triangle for herself. There’s Pierre (Pascal Greggory), the jealous jilted lover from long ago, a wind surfer with sharp feline features. The steadiness of his unrequited love for Marion, who turns him down at each advance, leaves him more and more embittered, less and less appealing, as the film progresses. Then there’s suave and swarthy Henri (Féodor Atkine), an ethnologist whose work in the South Pacific allows him multiple women in multiple ports. Henri is a playboy à la Hugh Heffner, silk kimono and all, and his life seems to revolve around the pleasures of the flesh. The characters all wear combinations of white and blue in every scene, a breezy stylized maritime look to the film, but it’s only the bad boys, like Henri, who wear red. They wave their flags clearly. Of course, it doesn’t stop Marion from running straight into Henri’s arms.

At first blush, this seems to be a film about Romance with the most capital R. Love exists as pure and abstract, divorced from any other axis of reality. It is the driving force to any life worth living, an all-consuming subject to be as discussed and dissected as it is felt. “Love burns. I want to burn with love,” Marion announces to the two men. “To spark a love in myself and in another, instantly and reciprocally.” “Passion that flames too quickly, burns out too fast,” steadfast Pierre retorts. For Henri’s part: “All my life I’ve loved and been loved. Now I’m fed up. I’m resting. I’m through with passion.”

The film owes clear homage to Pierre de Marivaux, the 18th-century French playwright whose comedies rest on the intricacies and subtleties of love. Marivaux’s characters, a contemporary critic wrote, “not only tell each other and the reader everything they have thought, but everything that they would like to persuade themselves that they have thought.” The same is often true for Rohmer’s characters. They are swept up in their narratives about who they are, worlds of words and artifice. Though the whole film turns around their love triangle, they barely seem to care about each other. They care far more about the stories they are telling about themselves. For them, the concept of being in love is far more important than the quotidian work of actual love.

Pauline at the Beach (1983)

For everyone, that is, except for Pauline. There is a quote at the opening of the film: “He who talks too much, undoes himself.” It’s ancient French, stiff and formal, taken from a 12th-century novel. On a closer viewing, one sees that this is the key. It is less a film about romance than it is about the self-delusions of adulthood, which Pauline, with the clear eyes of youth, resists at every turn.

If Pauline weren’t the titular character, it would be hard to tell that she was the film’s center. As Marion monologues about burning with passion, Pauline silently crosses the room, like to a stage direction, to sit in an unlit fireplace. As the adults talk in the foreground, Pauline often sits framed in the background—paging through a magazine, finishing her breakfast. The adults seem to be performing for her more than for each other. They try, almost desperately, to draw her into their games. They joke about seducing her, they demand her opinions on love, they push her into the arms of a boy her own age. They talk to her as if to an adult about their matters of the heart. The few times she speaks, it is to cut through their follies with startling clarity. “In fact, you don’t love her,” she tells Pierre of Marion. “You want her to love you.” “Why make him suffer if you love him?” she asks Marion of Henri, “You say that love can’t be forced, yet you want to make him love you.”

Pauline at the Beach (1983)

Pauline does have a brief romance with a local boy, Sylvain (Simon de la Brosse), but it is simple and tender, devoid of tricks. It lasts until Sylvain, too, is caught up in the machinations of the adults and Pauline is upset not by any deception but by his willingness to play at their games. Her physicality is important to the film, the 15-year-old-ness of her body, the way she glimmers between woman and child. It’s not a film whose sexual politics have aged particularly well, but there’s something undeniably truthful here about the power of a girl that age, how her refusal to grow up can be a daring act all its own.

In the last scene, Pauline and Marion are back in their car, the gates of the vacation home shut behind them. Marion, who doesn’t know the full truth of all the shenanigans played, proposes a mutual self-deception: they will each allow themselves to believe opposing versions of the same event, so as to best protect both their hearts. Pauline, who does know the full truth, and has no need for such deceptions, looks down for a second. Then, with a forced smile, she meets Marion’s eyes and agrees. It’s a pivotal moment. There, with that final breath, she enters the game. Summer is over, and it will never return, not the same way, ever again.

Pauline at the Beach (1983)

Share: