Oliver Laxe, photograph by Quim Vives

Interview

Oliver Laxe

The director of Sirāt on his latest odyssey into the desert.

The Burning Visions of Oliver Laxe opens at Metrograph on Friday, December 5.

Share:

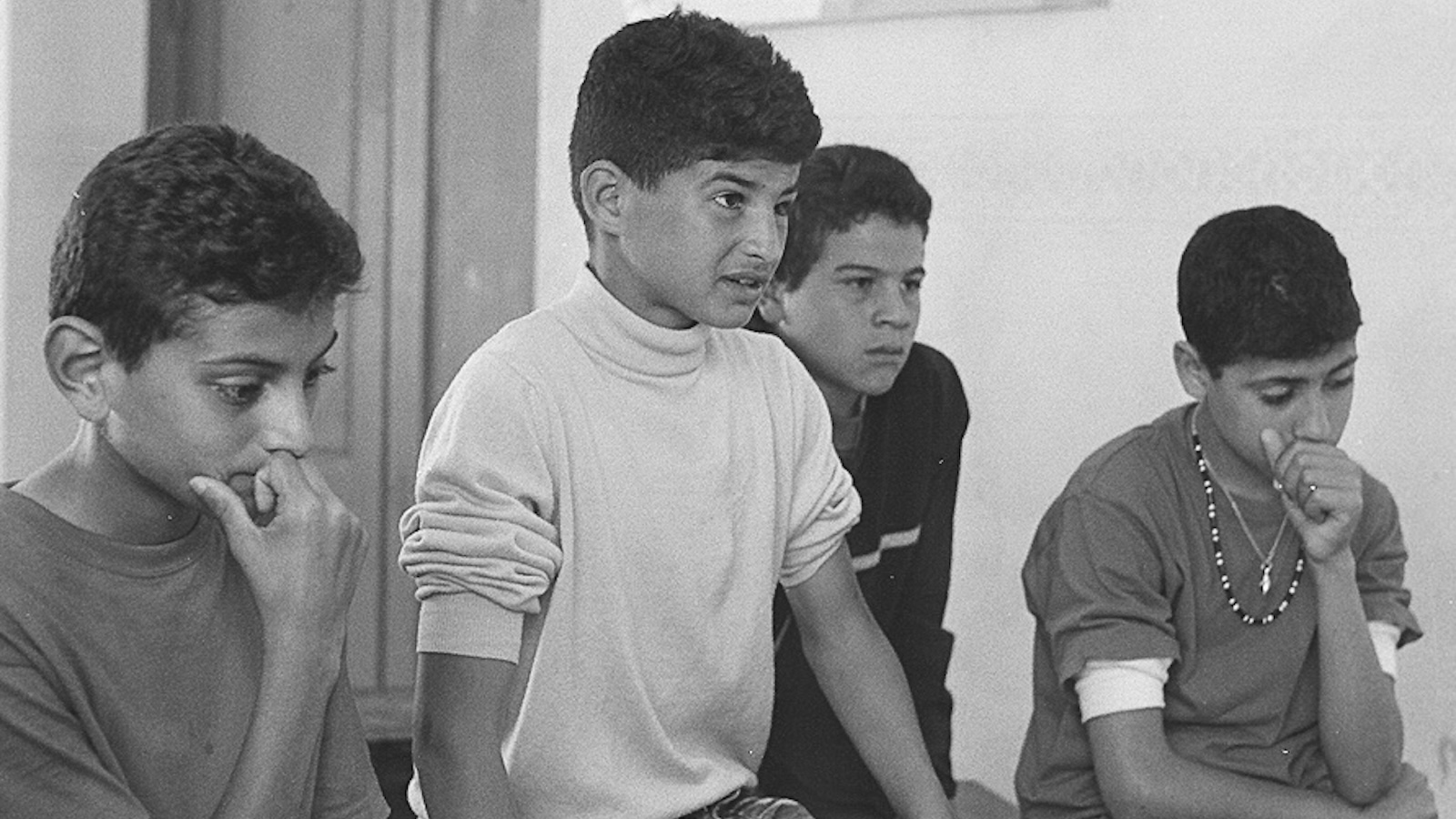

OLIVER LAXE IS A DIFFICULT director to pin down. On the level of form and storytelling, his films differ markedly from one another. He made his debut with the playful and poetic You All Are Captains (2010), a docufiction that doubles as a meta-reflection on the act of filmmaking. Laxe appears as himself, teaching a group of children in Tangier how to make a film. Before long, the kids tire of his domineering ways and artsy ideas. “This isn’t a film,” says one. “He picks scenes at random like fruit,” concurs another. And so they fire him from the production and he disappears from You All Are Captains altogether, which they then joyously take over.

Apart from an abiding predilection for casting non-professional actors, such hybrid experimentation was largely abandoned with Mimosas (2016). Moving freely between the present and an unspecified archaic era, Laxe’s mystical second feature follows three men on a mission to transport the body of a sheikh across the Atlas Mountains on horseback. Its minimalist, trance-like narrative harkens back to acid Westerns à la Monte Hellman, with an added Herzogian gravitas derived from filming in evidently forbidding—if not downright dangerous—circumstances.

The latter quality has become a mainstay of Laxe’s cinema. Fire Will Come (2019) saw him return to his home region of Galicia and trade the aridity of the Moroccan desert for the verdant ranges of the Galician Massif. This story of a taciturn arsonist who is released from prison and attempts to reintegrate into his old life among a rural community comes to a head with cataclysmic scenes of wildfires. Laxe and his team, who had undergone firefighter training, waited for actual forest fires to break out and then filmed from within the heart of the blaze.

Laxe’s standing as an auteur has risen film to film, with each of his four features having premiered and received awards in different sections of the Cannes Film Festival, culminating in his latest, Sirāt (2025), being invited to the main competition and winning the Jury Prize. Shot mostly in Morocco and titled after the bridge that according to Islam spans hell on the way to paradise, Sirāt relinquishes the contemplative pace of its predecessors. To an earthshattering score by techno DJ Kangding Ray, a small group of characters drive across the desert on an ever-more perilous journey to a rave, while beyond the horizon the apocalypse may be underway. A miraculous synthesis of the Mad Max filmsand The Wages of Fear (1953)—or, its more metaphysical remake Sorcerer (1977) is perhaps the better analog—Sirāt maintains a fever-pitch intensity from virtually the moment it opens on a wild party until the traumatic finale.

Despite the stylistic variety, there are distinct preoccupations that run through Laxe’s filmography, related to his belief in a profound affinity between cinema and spirituality. On the occasion of a retrospective at Metrograph, these offered a basis to discuss his practice and look back at his body of work to date. —Giovanni Marchini Camia

You All Are Captains (2010)

GIOVANNI MARCHINI CAMIA: We could start by talking about Morocco, as it’s such an important part of your cinema. I know that in your twenties you lived and worked there for a few years, which led to You All Are Captains. How did this relationship start?

OLIVER LAXE: I was living in London, I was 23. I met a few, we could say, poètes maudits from Tangier and I decided to go to Morocco before knowing Morocco. It was something intuitive. From the moment I arrived, I had a strong connection with the country. It was deep and strange. I have a really telluric relation with Morocco, I connect in a strong way with the culture, the values—and the landscape. I was in Tangier for four years and I made You All Are Captains. Afterwards, I had chances to go back to Spain, to work there, but I felt like I should stay and continue my dialogue with Morocco. That’s when I prepared Mimosas.

GMC: I’m curious about your engagement with the religion and spirituality of Morocco, as it informs all the films you shot there. Mimosas has been called a “Sufi Western,” for instance.

OL: People would tell me Mimosas is a Western, so I’d always correct them: “It’s an Eastern.” In French and Spanish, we say “l’Orient” or “Oriente”—it is a physical place and also a metaphysical one. I’m interested in tradition, and I have a strong dialogue with Islam and Sufism. Next month, I will spend two weeks on a pilgrimage to the graves of Sufi saints around New Delhi. This is part of my practice.

GMC: In the European arthouse tradition, spirituality plays a prominent role—and I know that such directors as Bresson and Pasolini are important to you—but it’s always in the context of Christianity. The influence of Islam on your filmmaking is unique within this lineage.

OL: In the end, no matter the tradition, you go to the essence. You take up one path and, through it, you go to the center. In cinema there is a strong tradition of artists who want to evoke the mystery; they want to evoke transcendence. And art is about proportions—every art, every language, is about geometry and spiritual geometry. Every artist has a kind of spiritual caste. It depends only on the percentage of essence and personality, or ego, that the artist has. You have both, so depending if you have more essence or more ego, your work will resonate more in a “transcendental” way.

Even though I have my spiritual practice, I’m still at the level of an artist, which means I have a lot of personality. I’m very attached to it, unfortunately, but I have a percentage of essence. That’s why Sirāt, in the end, is a kind of white sorcery. It’s not just a film, it’s a ceremony, it is itself a geometry that resonates on deep levels. But this is also relevant: I always protect the images from myself. At the beginning of the creative process, they are pure, organic, alive, and I have the strength to protect them, through the scriptwriting and production process. The images in my films still have this collective unconscious flavor; all the layers of symbolism, the universal archetypes.

It’s something that other filmmakers—like David Lynch, for example—are good at, they have images that are alive. Most images nowadays, they go from birth to death. Filmmakers are putting too much rhetoric, too much meaning, too many intentions, too many ideas into these images. The images are there to say something. They are dead, they have too much weight.

Mimosas (2016)

GMC: The narrative in all your films is guided by a quest. It can be a literal quest, as in Mimosas and Sirāt—bring the body of the sheikh home; find the missing daughter and reach the rave in the desert—or it can be more abstract, like You All Are Captain’s children filmmakers looking for something real in the countryside or the arsonist’s search for redemption in Fire Will Come. How does this archetype relate to the spiritual dimension of your cinema?

OL: I think art is about finding a balance between light and shadow, between masculine and feminine. That means a balance between what you want to say and what you want to evoke. Masculine is, like, the rhetoric, the author, the idea, the will to say something—it’s really egoistic: “I’m here. This is what I want to say.” And the feminine energy is more related to the subtle, the ambiguous, the polysemic, the esoteric, the lyric. Making art, from my point of view, is about finding this balance. Most art nowadays, obviously, is too masculine. The authors want to say too many things, so they don’t evoke anything. Or they want to express it in a way that is too logical, too rational; there is too much presence of themselves.

I like to consider my work as a kind of glass of medicine: it’s full of shadow, it’s bitter. But it’s also important to have light, to put some honey on the edge of the glass. Genre is the honey. Adventure tales have this balance between light and shadow. Human beings connect to it because we have this sensitivity, we’ve known these kinds of tales since the beginning of time. In these tales there is a physical path, but also a metaphysical one, a spiritual one. A Western has this balance: the hero has external challenges, but at the same time, he has subtle ones inside. I like adventures, but I choose them because it’s a good way to share things with the spectator—it’s good honey.

GMC: You mentioned your connection to Morocco’s landscapes earlier. Indeed, landscapes play a central role in your films, they are integral to the quest.

OL: I like to look for locations. It’s one of the most important things I have. I don’t want to intellectualize it too much. It’s just that I like what I feel when I’m in a place and I like to translate this into images. After living in Tangier, I was attracted to the wounded landscape of the Moroccan mountains. My family belongs to mountains in Spain, in Galicia—that’s where I was living when I made Fire Will Come—but the mountains in Morocco are more wounded. The erosion, the time—all the way back to the creation of the planet. You see all the layers, the strata, and you feel small. At my home, you feel small too, but the nature is more sweet. In Morocco it’s harsh, and I like this. I feel anguish, but also, through this anguish, I feel serene. Through anguish, through pain, we connect more with life.

And then, you have the desert. From the existentialism of the Moroccan mountains, where you ask yourself all the good questions—“What am I doing in this world? What is the meaning of being in this world? I’m just a zero, I’m nothing”—the metaphysical arrives, and the desert is the perfect landscape for metaphysics. In the desert, you have to surrender. You cannot hide in the desert: you are obliged to look inside yourself. I like that through the Moroccan landscape you can explore your limits as a human being.

GMC: If you consider your films chronologically, music seems to become more important, starting with the repeated use of excerpts from “Sinai” by OM in Mimosas. In Fire Will Come, Vivaldi’s “Cum Dederit” and Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne” are prominent, and then Sirāt features an extensive original soundtrack by Kangding Ray.

OL: It’s a process of being less and less complex, and accepting more and more that I’m a musician, too—accepting that music or sound comes at the beginning of my creative process. Sirāt is a film that started with dance. The images I had, I developed them dancing on a dance floor. In that moment, you are connected to your consciousness and to the collective unconscious; you are connected with the people you are with on the dance floor. It’s strong, in terms of channeling.

Then, in the way that [my regular co-scriptwriter] Santiago Fillol and I write, the images I have are really atmospheric. And music is about atmosphere. At some point, the way I imagine images is really, really linked to sound, to a kind of sonic landscape. Making music, it’s been more and more joyful for me. Working with Kangding Ray was the first time that I could work with a musician—imagine all the things I was discovering about myself, the way I work, my sensitivities. Working with Santiago and David Letellier [aka Kangding Ray], they are my two saints, as an artist. They are two tools that allow me to go far. I’m happy, I like this.

Fire Will Come (2019)

GMC: There’s a specific montage in Sirāt I’d like to ask about: you cut from the footage of pilgrims circling the Kaaba, to a character’s feet walking in the desert, to a close-up of the tarmac from the POV of the speeding truck, which evokes the perspective of a needle on a vinyl record. It’s such a beautifully conceived and constructed sequence, the way everything is synced to the slowly intensifying song on the soundtrack, bringing together many of the film’s themes.

OL: It was in the script, but we had shots of them driving that we didn’t put in the final edit. We would be watching Mecca, the Kaaba, and after we would see them driving. But I didn’t want to make a very long film. I wanted to make a film that was flying, tense, ready to attack. The structure had to be really sculpted. I wanted people to arrive at the end with energy, not tired.

This is one of the essential images of the film: to link the Quran, to link Islam and techno. I don’t know if there is a link between these two imaginaries, but inside me there is a link. At some point an artist has to take responsibility for himself: I have to look inside and accept what I see. There is something there related to, “What is life? What does it mean to go on a pilgrimage? What is sirāt?” I don’t want to analyze it much. I like this idea of “Let’s go!” It is the moment of the call of adventure, you get energized. When Santiago and me write, it’s about what you feel—synesthesia, you know?

GMC: I’d love to hear more about how you worked with Kangding Ray. There are so many sequences where the music, even down to the beat, corresponds to movements in the image.

OL: For Mimosas and Fire Will Come, I bought the tracks. That was also the plan for Sirāt, but finally I had the opportunity to look for a musician—and I wanted a musician, not a composer. We had time to work before the shoot: we started shooting with 60% of the music. The first things Kangding Ray sent me, he was composing. He was adapting himself to cinema. I said to him directly, “No, no, no, we don’t want composition. You are not telling a story. You are evoking something. I want music.”

My images want to say things, but they want to evoke, first and foremost. The challenge was to hear the image and to watch the sound. The way I talk about images, it’s really musical. When we talk about the grain of the image, for instance. I was very interested in Kangding Ray’s album Solens Arc, it’s really grainy—we used two tracks from this record. The way we use distortion in the film; in the last shot, when we see these train tracks vibrating, I wanted to really push that. The references we had were full of distortion.

The music has three dimensions. The first is physical—that is more techno and it’s more about physical catharsis. It’s related to traditional music. In Galicia, we have this—with the beat, with percussion. The second dimension is existential. In that sense, David could put a lot of feelings into the music. We have melodies, we have moments with pads [a type of synth patch that creates a sustained atmospheric sound]; we were working with feelings like afterglow, nostalgia. It’s full of David’s sensitivity. And then we have the third dimension, which is, again, when you ask the good questions, and the answer is to dissolve yourself, to just surrender.

At some point in the film the music is more sacred, more tonal, without melody. We were looking for “first sounds,” you know? There are these zooms at the end of the film, when we go inside the speakers—in a way, we wanted to do the same thing with the music. Electronic music is really good for this, to try to evoke the first sounds of the universe. I mean, it’s pretentious, but I think it’s interesting, the abstract place electronic music comes from. When you want to evoke transcendence, the mystery, these kinds of sounds are perfect.

Sirāt (2025)

Share: