Judy Irving

Interview

JUDY IRVING

BY YONCA TALU

The co-director of 1982’s Dark Circle, which has been restored and re-released and feels timelier than ever, recounts the long journey of making a film on the history and aftereffects of nuclear energy and how her documentary subjects have grown more heartening since.

The horrors of the atomic age have rarely been explored on screen with such insight and daring as in Judy Irving, Chris Beaver, and Ruth Landy’s award-winning documentary, Dark Circle (1982). Punctuated by Irving’s poised, heartfelt narration, the film charts the American nuclear industry’s devastating impact on human and animal life, in various settings that range from a radioactively contaminated Colorado neighborhood to modern-day Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Alternating between interviews, archival footage, and personal reflections, Dark Circle is a testament to cinema’s power to expose the truth in the face of deceitful authorities and their collaborators.

I spoke with Irving about the arduous journey of making Dark Circle and how she found comfort in immersing herself in the avian world for her following movies, The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill (2003) and Pelican Dreams (2014).

IN DARK CIRCLE’S OPENING MINUTES, YOU RECOUNT AN ANECDOTE ABOUT HOW DRINKING POTENTIALLY CONTAMINATED WATER DURING A VISIT TO DENVER AWAKENED YOU TO THE DANGERS OF PLUTONIUM AND LED TO YOUR DISCOVERY OF THE NEIGHBORING ROCKY FLATS NUCLEAR WEAPONS PLANT. WAS THAT THE STARTING POINT FOR THE PROJECT?

I had started to get interested in the nuclear issue in the mid-’70s because a ballot measure called the California Nuclear Initiative was coming up, and people were supposed to vote on whether any more nuclear power plants should be built in California. In 1976, I was in Denver, working on a film about Chicanos in politics, and I just picked up Denver Magazine one day. There was an article by Linda Harvey about the plutonium from Rocky Flats, which had contaminated the water supplies in Broomfield and Denver. It was especially shocking to think that we had been drinking contaminated water without even knowing about it. So I called Linda Harvey, who sent me these fantastic documents she had gotten from the Environmental Protection Agency. And that was the beginning of the research for Dark Circle, which took four and a half years to make.

HOW DID THE NARRATIVE DEVELOP OVER THE YEARS?

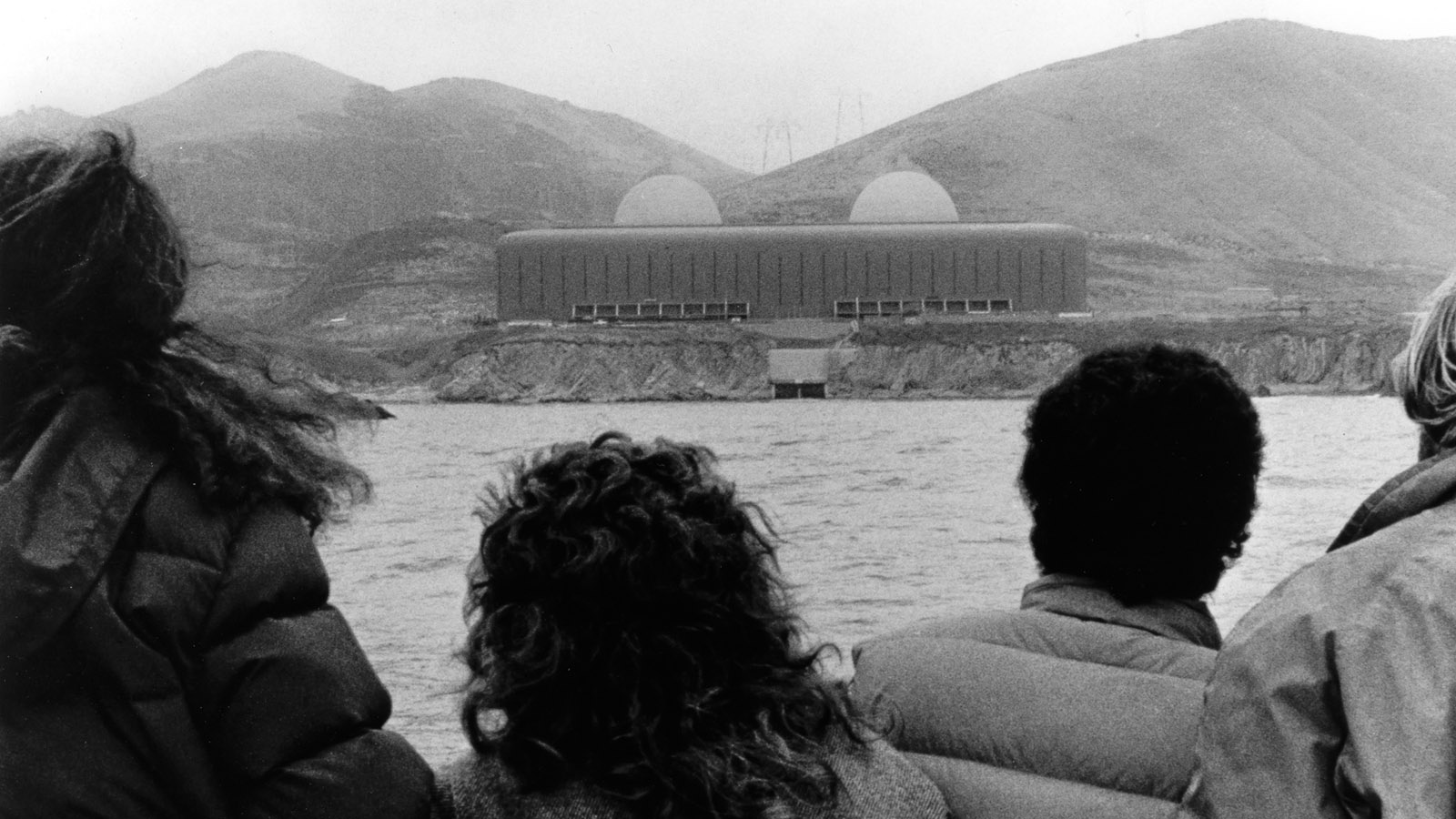

Our first major shoot was the non-violent occupation of the Rocky Flats railroad tracks in 1978, which temporarily prevented shipments from coming into the factory and plutonium from being made into triggers for nuclear weapons. Huge civil disobedience actions were simultaneously taking place in California against the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant, which was being built on an active earthquake fault. So we started shooting down there as well. Those sequences are actually at the end of the movie since we had to make a case for them—we didn’t want them to just be appealing to activists. We were trying to follow the trail of plutonium as it wended its invisible way from nuclear weapons back to nuclear power back to nuclear weapons, and I thought: “Wait a minute, why don’t we talk to people who actually experienced a nuclear blast?” And that’s how we ended up filming in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1979. But we also went down a fair number of blind alleys, like covering the entire Karen Silkwood case against the Kerr-McGee nuclear facility in Oklahoma, and when we did some rough-cut screenings, people said: “You have an embarrassment of riches. You need to cut at least one major location and one major person.” So we took out Oklahoma and Karen Silkwood, and made a whole separate film about her, a short documentary thriller called Hidden Voices, which includes an audio recording of Karen talking to her Union representative shortly before she was killed in 1974.

“WE ARE WAY CLOSER TO A NUCLEAR CATASTROPHE THAN WE’VE EVER BEEN. AND YET IT’S REALLY HARD TO POKE THROUGH THE ARMAGEDDONS THAT WE’RE ALREADY FACING—COVID, RAMPANT RACISM, THE UPCOMING ELECTION, CLIMATE CHANGE, YOU NAME IT.”

THERE’S A SCENE EARLY ON IN DARK CIRCLE IN WHICH THE PROJECT ENGINEER AT DIABLO CANYON GIVES YOU A TOUR OF THE PLANT. DID IT COME AS A SURPRISE THAT YOU WERE ALLOWED TO FILM IN THERE WHILE IT WAS STILL UNDER CONSTRUCTION?

It was a little surprising, but we knocked on that door for quite a while before we were finally given permission to go in. I’ll never forget filming that sequence. Chris Beaver was shooting and I was doing sound, and as we walked through the guts of that nuclear power plant—this labyrinth of pipes, wires, and blinking lights—we were both thinking: “Oh man, this thing is never going to survive an earthquake!”

THAT’S IRONIC, GIVEN HOW THE PROJECT ENGINEER BRAGS ABOUT THE PLANT’S SAFETY.

Right. What I love about making documentaries about contemporary issues as opposed to historic people or events is that you discover new things along the way. It’s ongoing now, and that’s the risk, because you don’t know where it’s going.

BOTH CHRIS BEAVER, WHOM YOU MENTIONED, AND RUTH LANDY ARE CREDITED AS CO-DIRECTORS ON DARK CIRCLE.

I met Chris and Ruth at the graduate film program at Stanford University—he was in the class ahead of me and she was a class younger, and we became friends. On Dark Circle, we were all jacks-of-all-trades. There’s a picture of the three of us where Chris is shooting, Ruth is doing sound, and I’m interviewing. Chris’s and my primary role was co-directing, and we fought a lot. [Laughs] He was a very good cinematographer, so he did more of the shooting and I did more of the sound recording, but we did shift off sometimes because I also loved to shoot. Ruth’s primary role was co-producing—she did a lot of fundraising in the last two-thirds of the project to make sure we finished right.

CAN YOU TALK ABOUT THE PROCESS OF WRITING AND RECORDING THE VOICEOVER NARRATION, WHICH BLENDS A JOURNALISTIC APPROACH TO THE EVENTS WITH A PERSONAL AND INTROSPECTIVE ONE?

We did a lot of rough-cut screenings with ordinary people and had them fill out anonymous questionnaires. What we learned from those was that we needed to dial down our own feelings about the nuclear issue, and really let the film create outrage in the viewer without putting it into the voiceover. So that’s why the final version is kind of neutral. I really wanted to stay behind the camera, where I’m most comfortable. I didn’t want to narrate Dark Circle. In fact, we did a screening with Ellen Burstyn, where I was doing a rough narration just so that she could hear what she might be saying. And she looked at me and said: “You have to do this narration. You’re the only one who can tie together these places, people, and thoughts. Don’t get an actress.” I had never narrated my own movie before, but I realized she was right. The voiceover was written over many years and recorded in a closet in my apartment in Noe Valley, which is a relatively quiet section of San Francisco. But even so, I was up at 3:30 in the morning to record some lines before the buses started running. [Laughs] This is the opposite method of writing the script, then going out and filming postage stamps that illustrate what you’ve already written. That, to me, could not be more boring.

DID YOU COME UP WITH THE IDEA OF DRAWING PARALLELS BETWEEN THE AMERICAN AND JAPANESE VICTIMS IN THE EDIT?

Those parallels came up as we were shooting. Pam Solo, the activist for American Friends Service Committee, told us about Richard McHugh [the Navy veteran in the film], who was living near Denver. He was the one who said that the bomb was being used against Americans. So when we shot his interview, the questions I asked allowed him to make that point again. He felt that he had been bombed, and he was—he flew through an atomic cloud and got leukemia later. So it was pretty obvious that folks were being affected by plutonium not just in Hiroshima and Nagasaki but also in places where nuclear weapons were built and tested, and where nuclear power was pushed as a source of electricity. When I first started reading about nuclear power, it was a revelation to find out that plutonium is produced in nuclear power plants as a waste product. Those are things that the nuclear industry doesn’t want us to know.

HOW DID YOU MEET SUMITERU TANIGUCHI, THE NAGASAKI BOMBING SURVIVOR WHOSE TESTIMONY YIELDS ONE OF THE FILM’S MOST POIGNANT AND UNSETTLING MOMENTS?

Some very good friends who were connected to the YMCA [the Young Men’s Christian Association] were taking a peace group to Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1979, and they invited us to go along. We were hooked up with a fantastic translator, Kaori Seo Kurumaji, who has done relentless peace work all her life. We said that we wanted to film interviews with survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Kaori and another activist set us up with three people in each city. We were told that we were the first Americans to ever film interviews with survivors of the atomic bomb. At first we didn’t believe it, since the war had ended in 1945, but it was true. They had talked to American writers, like John Hersey, and had been photographed by still photographers, but because there was a news embargo on Hiroshima and Nagasaki for many years in the United States, no film crew had bothered to go. So the interviews we conducted in Japan are really historic and still quite useful because the folks who lived through the bombings are now dying or getting toward the end of their lives. Mr. Taniguchi died in 2017, and the remastered version of Dark Circle is dedicated to him. I shot his interview myself, and I feel very proud of that. I just honor him, you know; I respect what he went through so much. The American Army had taken pictures of him and his horrible [skinless] back following the explosion. And years later, he went to an exhibit in a museum and saw this photo of himself lying in the hospital. The caption said: “This young boy died of his wounds.” So he went to the curator and said: “This young boy did not die. I am that young boy.” He was a very brave man, and he spoke out for his whole life about what the bomb had done and why it should never happen again.

HOW DID YOU GET ACCESS TO THE FOOTAGE OF THE PRISCILLA TEST, IN WHICH THE U.S. MILITARY SUBJECTED LIVE PIGS TO ATOMIC BLAST EFFECTS? HAD IT BEEN DECLASSIFIED BY THEN?

Chris Beaver did incredible sleuthing to find all the stock footage in Dark Circle. He is persistent and relentless, and was able to access archives that don’t even exist to the general public. There was an archive in Santa Barbara, California, called the DASIAC [the Defense Atomic Support Information Analysis Center], but it was in a building with no sign. I don’t know exactly how Chris found out about it, but he contacted them and said that he would like to look at footage of atomic tests, particularly on animals, vehicles, and people. He was stonewalled for a really long time, and then they finally said: “Well, you can come to the library, look through our 100,000-page list of tests, and pick out what you want.” So when he got there, he quickly went to the Priscilla test because he had read about it in his research, and requested it along with other tests. But he was told that they were all classified. However, the librarian who was there that day left somewhere during the making of our film, and a new librarian came in. So Chris asked again: “By the way, we requested these tests before, and you haven’t sent them yet. Would you please do so?” And the new librarian did! This is U.S. government footage, so it belongs to all of us. If you could get your hands on it, it can become public.

DID YOU GET INTO ANY TROUBLE FOR INCLUDING THAT FOOTAGE IN DARK CIRCLE?

No, but when we tried to put the movie on public television, we encountered a pushback that led to a censorship fight, which lasted until 1989. Dark Circle was originally accepted by PBS for national broadcast in 1985. But when the powers that be in Washington, D.C. looked at it, they said we needed to cut the arms convention sequence, where these companies get together and sell arms to various buyers. Kevin Rafferty, a very good friend of ours, was making The Atomic Cafe with his brother Pierce and Jayne Loader around the same time as we were making Dark Circle. We agreed to keep our film contemporary, while they decided to use only stock footage so that we wouldn’t step on each other’s toes. But meanwhile, Kevin had shot the arms convention sequence, and he let us have it. So we added that little animated montage at the end with the logos and slogans of the companies that build the elements that go into the hydrogen bomb, and we refused to give that scene up. But then in 1988, PBS established a brand-new TV series called POV, where they could basically say: “This is the filmmakers’ point of view, not ours.” Dark Circle aired in POV’s second season and went on to win an Emmy Award for News & Documentary that year.

DARK CIRCLE READS LIKE A CAUTIONARY TALE AND RESONATES POWERFULLY WITH THE APOCALYPTIC TIMES WE ARE LIVING IN.

The only thing I could say in the closing narration was: “Don’t rely on experts.” It was true, and it’s still true now. We have to rely on ourselves. We cannot rely on the so-called scientific or political experts who got us into this mess. And what’s really scary to me is that the atomic Doomsday Clock has been set to 100 seconds to midnight. It was eight minutes to midnight when we finished the film. So we are way closer to a nuclear catastrophe than we’ve ever been. And yet it’s really hard to poke through the Armageddons that we’re already facing—COVID, rampant racism, the upcoming election, climate change, you name it. Who needs another Armageddon? But this one could wipe all of that out in a matter of a few days. So it would be really great if we could get this issue on the front burner as well. Our current president can unilaterally deploy nuclear weapons. That needs to change, too.

“AFTER A DECADE OF FOCUSING ON THE NUCLEAR ISSUE, BOTH CHRIS BEAVER AND I NEEDED SOMETHING MORE UPBEAT AND THAT DIDN’T CREATE NIGHTMARES.”

WAS IT A CONSCIOUS DECISION FOR YOU TO FOLLOW UP DARK CIRCLE WITH SUCH A SOOTHING AND GRATIFYING MOVIE AS THE WILD PARROTS OF TELEGRAPH HILL?

After a decade of focusing on the nuclear issue, both Chris and I needed something more upbeat and that didn’t create nightmares. So we made a series of environmental shorts about the San Francisco Bay, Greenbelt, and Delta, which were on local public television. But I also wanted to do my own film after many years of collaborating with Chris, and I wanted it to be something less dyed-in-the-wool and more creative, something personal.

UNLIKE DARK CIRCLE, YOUR VOICEOVER IS INTRODUCED MUCH LATER INTO THE WILD PARROTS OF TELEGRAPH HILL, WHICH BEGINS LIKE AN OBSERVATIONAL PORTRAIT OF MARK BITTNER AND THE BIRDS.

Like Dark Circle, The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill took four and a half years to make, so the story evolved along the way. And part of that story was that Mark and I became really good friends, then my life changed [Irving and Bittner fell in love and got married], and I couldn’t predict any of that at the beginning.

YOU MENTION IN THE WILD PARROTS OF TELEGRAPH HILL THAT MARK REMINDS YOU OF YOUR GRANDFATHER, WHO WAS ALSO AN ORNITHOPHILE AND WHOSE LEGACY SEEMS TO HAUNT ALL YOUR WORK, INCLUDING DARK CIRCLE AND YOUR THIRD FEATURE, PELICAN DREAMS.

My grandfather was a really important character for me when I was young. He taught me about birds, and we had a little game called “bird lotto,” where you could win if you knew the bird’s name. On Dark Circle, we shot the migration of the black brant [goose] in Alaska, and I started wondering how plutonium affected them and the natural world. So I talked about my grandfather there. And when Mark was feeding the birds [in The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill], it just reminded me of when my grandfather taught me how to feed chickadees with my hand out and the seeds in my palm. That picture of me and my grandfather [a motif in Irving’s films] is the only one I have. He’s holding me up to the spotting scope, so we’re obviously looking at birds, and I just took creative license. In The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill, I said we were looking at ducks, and in Pelican Dreams, at pelicans.

I LOVE THE SCENE IN THE WILD PARROTS OF TELEGRAPH HILL IN WHICH MINGUS, THE FIRST PARROT THAT’S INTRODUCED, IS LEFT ALONE OUTSIDE, AND WE HEAR ALL THESE THREATENING SOUND EFFECTS, SUCH AS CROWS CAWING AND HAWKS SCREAMING, THAT SEEM TO HAVE BEEN ADDED IN POST. IT’S A COMPELLING EXAMPLE OF HOW AN ELEMENT OF FICTION CAN BE USED IN A DOCUMENTARY TO HEIGHTEN REALITY.

Exactly. Any good documentary makes use of dramatic techniques: not only the three-act structure but also sound effects. Often when you record sound outside, all you get are airplanes and cars. So you need to massage the soundtrack to make it do what you’re going for. In the case of Mingus, I used sounds that he would have heard all the time outside, although not necessarily together.

WHEREAS MARK SERVES AS A MEDIATOR BETWEEN YOU AND THE AVIAN WORLD IN THE WILD PARROTS OF TELEGRAPH HILL, HUMANS APPEAR ONLY AS SUPPORTING CHARACTERS IN PELICAN DREAMS, WHICH STEMS FROM YOUR OWN FASCINATION WITH AND CURIOSITY ABOUT THE BIRDS YOU CALL “FLYING DINOSAURS.”

Often when I start filming something, it’s with the intention of making a short hobby movie. That’s how I started The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill, which was supposed to be a 20-minute film for kids, but also Pelican Dreams. I had always loved pelicans and decided to make a valentine to them. So I had lunch with the guy who ran the International Bird Rescue Center in California and told him I wanted to make a movie about pelicans, and he said: “Fine, you can come up and film in the pelican aviary, and we’ll give you a run of the place.” But a few weeks later, this tired and hungry pelican landed on the Golden Gate Bridge and provided me with the beginning of my film—it was like a psychic gift from the cosmos. A friend of mine was in the traffic jam caused by Gigi [the pelican’s nickname], and she e-mailed me and said: “You’ll never guess why I was stopped on the road today.” Then Mark went online and found the YouTube video of Gigi on the bridge, and I was able to get permission to use it.

WHILE PARROTS ARE HIGHLY VOCAL, PELICANS COMMUNICATE WITH THEIR BODY LANGUAGE AND PERFORM IMPRESSIVE CHOREOGRAPHIES, LIKE DIVING INTO THE WATER FROM A GREAT HEIGHT TO CATCH FISH, WHICH YOU CAPTURE IN STYLIZED SLOW-MOTION SHOTS.

I started out by reading a very little-known monograph by Ralph W. Schreiber, who lived in a pelican-breeding area in Florida for a long time and translated the pelicans’ gestures. When pelicans are young, they vocalize their hunger, but as they get older, they become silent birds. And I thought about how cool it would be if I could film their behaviors, then tell people what they meant—in other words, create a language for a bird that has no voice. Likewise, the diving has always seemed to me to be a really difficult, almost impossible way to get your food—flying 50 feet high, looking down and spotting a fish, taking a bead on it, turning your body a little bit, then closing your eyes just before you go into the water, which opens your bill, and hopefully catching the fish. I mean, who dreamed that up in the world of evolution? So I wanted to take the diving apart and show people step-by-step how it’s done, hence the slow-motion shots, which we filmed at the Channel Islands with the Phantom camera.

I’M CURIOUS TO KNOW IF YOU HAPPENED TO TRIGGER CERTAIN SITUATIONS IN PELICAN DREAMS, AS WHEN MORRO, THE INJURED PELICAN WHO LIVES IN THE BACKYARD OF A COUPLE OF WILDLIFE REHABILITATORS, COMES INTO THEIR HOUSE.

Morro’s caretakers, Bill and Dani Nicholson, used to have a curtain over the glass panel on their living-room door. One day, they took it down, and Morro, who was exploring around the house, hopped up onto the porch and saw a reflection of himself in the window. So he started pecking at the door, and Dani called me right away and said: “I think Morro wants to come inside.” And I said: “I will be right down.” The only thing we did when I got there was to leave the door slightly ajar, so that Morro would open it himself when he pecked at it. And I was there with the camera and sound, ready for him, without knowing at all what would happen. I love that scene because you can see Morro’s trepidation at discovering a brand-new world. Has a wild pelican ever been in a place with a roof, let alone in a house with couches, chairs, and a fireplace?

DO YOU FEEL ANY AFFINITY WITH AGNÈS VARDA? I ASK BECAUSE YOUR WAY OF MIXING THE PERSONAL AND THE POLITICAL, BUT ALSO HUMOR AND TRAGEDY, KEPT REMINDING ME OF HER FILMS.

Yes, I do. But one of the filmmakers who influenced me the most is actually Barbara Kopple. When I was cutting my teeth on filmmaking, I loved Harlan County, USA [1976]. It was a really well-made movie about an important subject, with transitions done with music, and Barbara was just there with her camera—she didn’t know how it was going to turn out, and she was in danger. So I wrote to her and got to know her. And she became not only a film mentor to Chris and me, but also helped us get started as freelance, independent filmmakers, which we’ve been ever since.

BOTH THE WILD PARROTS OF TELEGRAPH HILL AND PELICAN DREAMS ARE ROOTED IN THE LIFE AND CULTURE OF SAN FRANCISCO, WHERE YOU’VE BEEN BASED SINCE 1976, AND I WONDER IF YOU WOULD CONSIDER YOURSELF A LOCAL FILMMAKER WITH UNIVERSAL AMBITIONS.

It’s true that since Dark Circle, I have created more of a local interest in my films, partly because I live in San Francisco and am trying to understand my world. The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill takes place almost entirely on the Greenwich Steps on Telegraph Hill, and it was so easy to shoot that movie compared to Dark Circle, which required us to travel a lot. I think that ultimately all stories that resonate with people are local ones about individual human beings, animals, or relationships between the two. And if you go deep enough and focus in a humble enough way to actually see what’s happening, then your story speaks to people who don’t live in the same place, but can relate to it through experiences they might have had in their own lives. So I’m interested in continuing to plumb San Francisco with my camera, and I’m working on another feature right now called Cold Refuge, which is about why in hell people swim in the Bay. [Laughs] I’ve been a Bay swimmer myself for 34 years, and this project was literally going to be 10 minutes of funny stuff about how people talk themselves into going into cold water, but it immediately morphed into something much deeper. The people I started filming had real stories about grief, mourning, and depression. For instance, there was a black swimmer who had never learned to swim as a kid because he didn’t have access to the beach, and his parents didn’t have money to pay for lessons. When he was 13, he was out on this research boat with some biologists, and he saw one of the crew members swimming, so he said: “That looks great. Can you teach me to do that?” And the biologist replied: “Hey kid, Black folks don’t swim.” It took Naji Ali 30 years to get over the humiliation, trauma, and racism. But now he’s a long-distance swimmer and a member of the South End Rowing Club in San Francisco, where I met him. •

Yonca Talu is a filmmaker and film critic living in Paris. She grew up in Istanbul and graduated from NYU Tisch. She is a regular contributor to Film Comment magazine.