Interview

Jem Cohen

An interview with the New York–based filmmaker about his long engagement with music made—much like his cinema—outside of mainstream channels.

Share:

If Jem Cohen were a member of MI5, and was involved with a variety of intelligence gathering activities, you might say he’s across several desks. As a filmmaker, he is across almost all of them: 16mm film, high resolution video, features, documentaries, what were once called music videos, fiction, nonfiction, verité, and plain old abstractions. Cohen began making films 40 years ago, and in that time he’s stayed close to the live music community, even when he was making films about museums (Museum Hours, 2012) and the act of counting (Counting, 2015). He made the definitive Fugazi documentary, Instrument (1999), which apparently exists somewhere as a six-hour cut. He filmed Elliott Smith at the height of his powers (Lucky Three, 1997) and does live film projections for both R.E.M. and Godspeed You! Black Emperor. His latest feature film, Little, Big, and Far (2024), which will be released theatrically in 2025, is only lightly connected to music but the few bits are crucial. Several scientists discuss the cosmos with the help of an Alice and John Coltrane track, briefly, while much of the film is scored by Xylouris White, featuring longtime Cohen collaborator, drummer Jim White. I met up with the filmmaker met at his West Village loft to discuss his career. —Sasha Frere-Jones

SASHA FRERE-JONES: How did all of this start?

JEM COHEN: To make my first film, I took a leave from college and worked in Florida for a little filmmaking company, a mom-and-pop outfit that made industrials for a living. They took me under their wing and taught me the nuts and bolts while I worked as their shipping clerk so I could borrow their 16mm gear. That film, a local portrait which sits right between fiction and nonfiction, includes the Everly Brothers’ “Down in the Willow Garden” and Gun Club’s “Mother of Earth.” The songs run with images I shot driving on back roads, usually when I was alone. I loved those songs and they’re integral to the film, but I certainly wasn’t thinking I wanted to do music videos. This was the very early days of MTV, before the industry congealed into this grotesque advertising behemoth. No one was even sure what a music video was.

SFJ: What was the name of that one?

JC: It’s called A Road in Florida (1983).

SFJ: You were born in Afghanistan, right?

JC: My dad was working in early childhood education for Columbia University and USAID, helping with schools, so I was there for just a couple of years.

SFJ: Where did you grow up in the States?

JC: I grew up in DC and went to public high school with a small group of newly minted punks, including Ian MacKaye. 1977 was a pretty good year to be in Wilson High School and it’s fair to say that music became our lives. DC was so adrift between West Coast and East Coast. Because DC was so not—

SFJ: You don’t think of it as East Coast?

JC: I mean adrift between the music industry hubs of LA and New York. DC was left out. It felt like the industry couldn’t have cared less about DC.

SFJ: It’s not a music business town.

JC: No, and this was way before the so-called grunge trend where the industry became obsessed with finding scenes in Seattle, Minneapolis, wherever. Maybe some musicians in DC were a little disgruntled about being ignored but it was very freeing. Nobody was thinking about being part of the business or trying to get noticed or get careers. It was just sheer enthusiasm. New York had the Ramones and all that but seemed a bit decadent. We saw every new band that came through. The pivotal moment was when The Cramps played a benefit for the local college radio station that we all depended on, WGTB, which the Jesuits wanted to shut down.

SFJ: So this was like the Sex Pistols show at the Manchester Lesser Free Trade Hall in 1976, when Pete Shelley and Morrissey and Mark E. Smith were all in the audience.

JC: Exactly. We were all there. Bad Brains were there, Ian was there, Guy Picciotto [of Fugazi] was there, most everybody we knew in this new wave and punk scene.

SFJ: What when did this happen?

JC: February of 1979.

SFJ: Bad Brains were already playing, right?

JC: Bad Brains were already untouchable. Because they’d been jazz musicians, they came into punk ready to rip and they brought in reggae too. They were able to play so fast and so tight whereas my high school friends who were forming bands were literally like, “How do you play this instrument?” Few if any had even had music lessons. Seeing Bad Brains in a tiny room like at Madame’s Organ—which was in Adams Morgan, a neighborhood in DC—was incendiary. When they put out their first single, they just drove up to Wilson in a station wagon and handed it out for free. That’s how I got my signed 45. It was just because they knew there were like 11 punks there who would appreciate it. Everybody I knew was forming bands but I wasn’t a musician, so I drew flyers and took some stills. I wish I’d taken a lot more.

We all went to most every show, often using fake IDs, whatever the genre—new wave, punk, rockabilly, psychedelia, garage. Ian saw more than I did. It was a beautiful era. While we were quite open-minded in terms of genre, we weren’t as open-minded in terms of sonic experimentation, which all seemed a little arty to us.

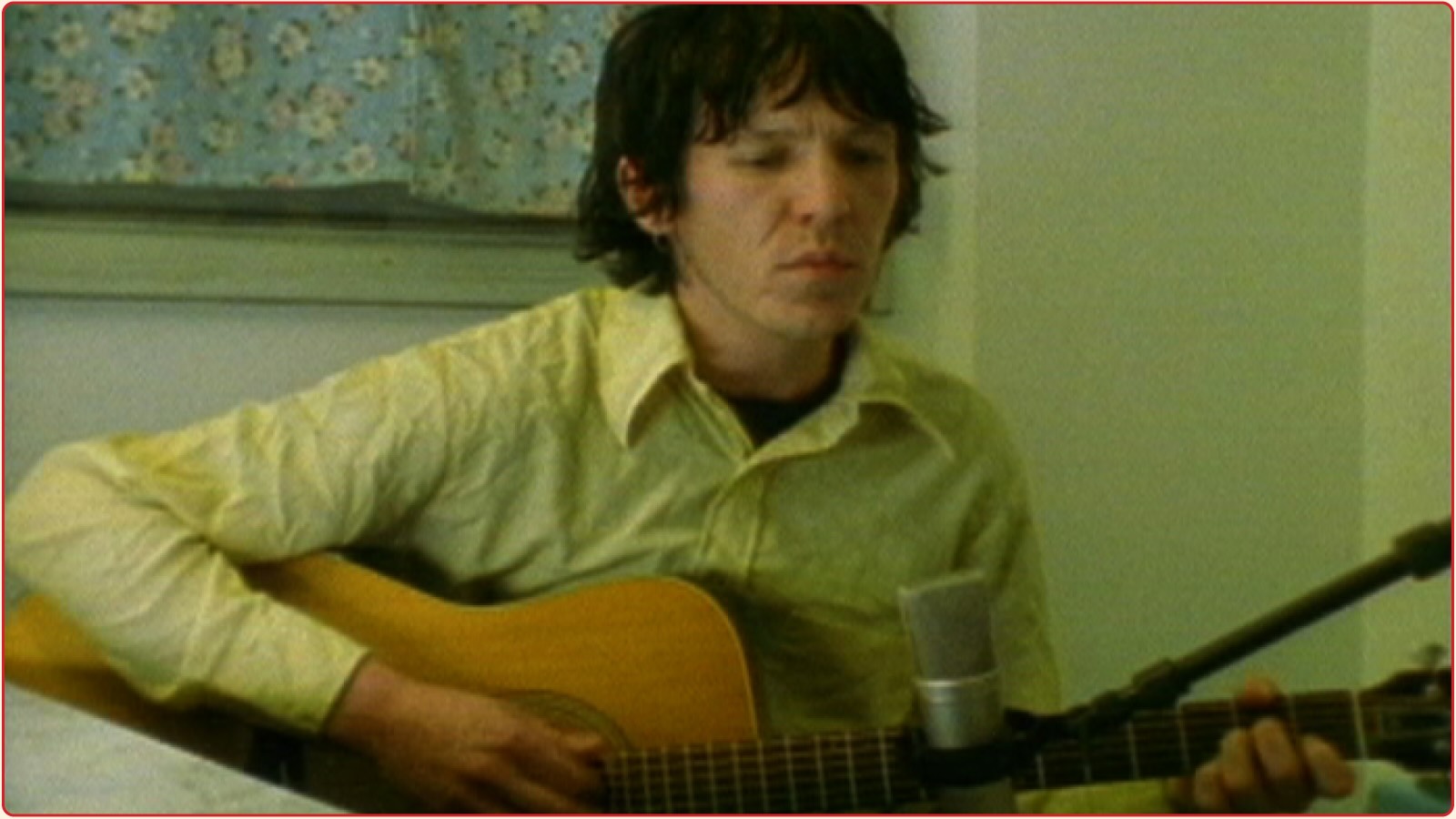

Lucky Three (1997)

SFJ: How did the music videos start?

JC: I went off to college, which a lot of my DC punk friends opted out of, and studied photography and film and my family moved to NYC. “Glue Man,” on the first Fugazi record, was in large part generated because the band came through Brooklyn to visit. I was living in a then very quiet industrial Williamsburg. I shot some footage from my rooftop of a guy huffing glue down on the street below. I didn’t set out to film it, really. The roll was a portrait of the street and the Williamsburg Bridge and the sky and then this guy comes along, and I’m just filming whatever is happening. I showed it to the band because it was very heavy and troubling, and I didn’t know what to make of it. I was in the habit of projecting Super 8 on my wall when they visited, so I included that, and they went off and came up with the music out of seeing the footage. I’d written a sort of poem about it too, so I donated my words, and Guy wrote lyrics in response, and the song emerged. Then I decided to do the film Glue Man (1989), which was a kind of deconstruction of the song. I went into the studio with Ian, and we isolated elements of the tracks. It became clear to me that it was a kind of anti-music video in every respect—form, subject, intent. I eventually did another film project with Ian called Black Hole Radio (1992), and documented Fugazi from an early basement practice at Dischord House on, which led to INSTRUMENT.

SFJ: How do we get from that to R.E.M.? Maybe we skipped a step.

JC: In college I heard the first R.E.M. single [“Radio Free Europe”] and loved it. On the strength of that one song, I went to see them open for The Ventures at a tiny club in New Haven in 1982. A few years out of college I sent them some Super 8 films on VHS, one of which was This is a History of New York (1987), a document trying to make sense of all of New York City, and the other, Witness (1986), of the Butthole Surfers, who MacKaye had tipped me to. I just sent them down to Athens, Georgia. Stipe watched History of New York and invited me to adapt it for their “Talk About the Passion” video, but I ended up shooting mostly new material.

SFJ: On Murmur, but this is way after, right?

JC: If I recall, the video was done when they put out the Eponymous collection [in 1988]. I’d gotten wind somehow that Stipe had been an art student and into experimental film. And his teacher James Herbert, who did these beautiful, re-photographed, 16mm films, was tapped for some of their early videos. One was just the band wandering around in the yard of R. A. Miller’s spinning folk-art. What blew my mind was that the song ends and the film keeps going and then the next song comes on—so it was set free from the product-based parameters of music video, which had to conform to the song.

SFJ: The first show I saw was at the Beacon, maybe 1984 or 1985. Stipe had really long hair and was wearing a baggy suit. He kept twisting around like he was trying to hide inside his clothes. We couldn’t understand the words or see his body. Ten years later, R.E.M. were doing these big stadium shows and he was throwing himself around shirtless. It seems reductive to perceive both moments only in relation to whether or not he was out, but it would be crazy to not consider that. I just love that band so much, still.

JC: By the time I got hired to do film work for the Green world tour, they were becoming a very big band. Michael and I are friends to this day, he’s a very thoughtful, interesting person. People lose sight of some early aspects of his life because he became a celebrity, but he came out of the Velvet Underground and Patti Smith and Pylon and Vic Chesnutt, you know?

SFJ: He repped so hard for Vic.

JC: The world is deeply indebted to Stipe for dragging Vic into the studio to do the first and second records. I was friends to both of them when Pete Sillen made his documentary [Speed Racer: Welcome to the World of Vic Chesnutt, 19941993] and sat in on the West of Rome session and shot some bits and pieces for Pete’s film. Vic became maybe the most important musical, artistic force in my life for many years. I ended up producing one of his last records, North Star Deserter, backed by the Godspeed You! Black Emperor folks, Guy Picciotto, Hanged Up, Frankie Sparo folks, and more. A very powerful experience. I think that was one of the greatest bands ever to walk the earth—or roll across it, in Vic’s case. And we all did a big show in Vienna of projections with live music, Empires of Tin, based around writer Joseph Roth, the Habsburg and George Bush empires, and Vic’s songs.

So, it became a life of trying to do things with music and musicians that wasn’t typical music video or typical film scoring. Sometimes the most important thing to do with musicians was document them in an almost anthropological, observational way, and sometimes I just wanted something visceral and raw, to get at how the band feels or the music feels, and sometimes the band shouldn’t be seen at all, just images and sound. My early development was concurrent with the rise of music video but it became such a betrayal, I was disgusted when MTV became this dominant force. I’d had very high hopes, thinking, “Oh, here’s a realm where musicians can work with filmmakers,” but it so quickly becamebecome formulaic, with a few wonderful but rare exceptions. I still love some early videos by The Residents.

Or Nothing (2022)

SFJ: It was so rare to see something that wasn’t lip sync.

JC: Even in places where you thought you could get around it! Jonathan Richman was asked to do a music video even though he didn’t really want to. Someone said, “Hey, Jonathan, there’s this guy in New York who also doesn’t like lip-sync.” So I shot “I Was Dancing In The Lesbian Bar” live, no lip-sync, but, to my horror a bona fide record executive wanted background singers dubbed in, just because they were on the single! And I was like, “I filmed him live, they’re not there. What the hell are you doing?”

SFJ: Selling the toothpaste.

JC: Selling the toothpaste. But at least the band wasn’t lip-syncing.

SFJ: So, you’re friends with this DC cohort, and you get to know R.E.M., and you’re beginning to put stuff in the world, a lot of which has to do with music. And you’ve kept going with music work for decades, up to now—like the recent Jim White/Marisa Anderson [Aerie, 2024]. But let’s talk about the Elliott Smith film, Lucky Three, where he does “Between the Bars” and “Angeles.”

JC: It’s nice to show Lucky Three big at Metrograph. It keeps circulating online in wrong aspect ratios or chopped into separate quote-unquote music videos, which they were not. The idea was to make a film, and to make a point about what a music film could be. To just watch this beautiful musician make music.

SFJ: What’s the third song?

JC: Big Star’s “Thirteen.” Such a sweet cover. I was in love with Elliott’s music from the first record. Lucky Three was a truly independent project, not even made at the behest of his label. He wasn’t really famous yet—it’s shot right at the crossroads—and it’s a different universe when you can approach musicians without fighting past managers or agents or major labels. He’d seen some shorts I’d shown at the Olympia Film Festival and then when I was passing through Portland with my sync sound camera I wanted to do a little film, just hoped to get a song or two. But he was so good at it that he’d nail the song on the first or second take, so finally it was, “I’ve got exactly enough to do one more, can you play ‘Thirteen?’” I’d heard him play it live without realizing it was a cover, which is embarrassing.

SFJ: I have three favorite Elliott songs and two of them are “Between the Bars” and “Angeles.”

JC: “Angeles” says a lot about having to talk to people in suits when you’re not really ready or able to do that. When filming Elliott, I just asked, “Can we drive around Portland and go to some places that are important to you?” We were standing somewhere, and I see these two businessmen in the background having a conversation and just swing the camera over. Pure chance, but it made all the sense in the world in terms of the lyrics so it ended up in my edit. I guess on the way to or from Portland I went through LA and grabbed some shots there, which also made sense.

SFJ: Your relationship to film scores is a little different, and we seem to agree about rejecting the use of diegetic music as manipulation, or at least being careful with that button.

JC: Museum Hours has no score except two times that Mary Margaret O’Hara sings. She’s one of my very favorite musical entities but I wasn’t planning to have her sing in my film; I just wanted her presence. But then I was like, “You know what, her character should sing.” It’s very organic to the film. But there’s no score.

When I teach, I don’t let the students put non-diegetic music in their assignments because they have to learn to not lean on it. I have a very complicated relationship with music in my own filmmaking. I do whole films where, because of that problem, I just skip it, but then I have this whole other part of my life where I collaborate with musicians and do projections with live accompaniment, and that’s a different game. Those projects are often called Gravity Hill Sound+Image.

SFJ: Tell me more about Gravity Hill.

JC: That’s just my umbrella for various projects. Gravity Hill Sound+Image refers to shows I organize of projections with live music, done with a revolving group of collaborators as a means to explore unusual ways to conjoin film and live sonics. Usually each event begins with silent film and ends in darkness with only music or sound. I came up with it after working on both small and large scales for other people, the most extreme example being work for R.E.M. in which we managed to realize some pretty outrageous things. Like, I’d done their “Nightswimming” video and a lot of that’s shot underwater in Super 8. They wound up touring with multiple 35mm projectors and a translucent opera gauze cube around the band to project on. It was very, very beautiful and could be done in stadiums, because they had the wherewithal. I’m really thankful for those times, though I did sometimes get alienated by the gigantitude of the pop touring machine. They’d entered a zone where it became more like theater, with lighting designers and stage designers, and everything tightly mapped out.

SFJ: The opposite of $5 tickets.

JC: Yes, but it was counterbalanced by being able to realize things you’d never be able to on your own, like having Super 8 footage blown up to 35mm or 70mm and projected.

SFJ: How the hell were they touring with a 70mm projector?

JC: They hired this projection outfit out of Boston with a whole truck and they literally lifted remote controlled 35mm projectors up in the air and in the back 70mm! I did a film thing with the visual artists, Mike and Doug Starn, strange and beautiful footage of this spinning light sculpture, and R.E.M. projected it in 70mm. They had to be the only band doing something that crazy on that scale, when every other big band had gone to video, which is so much easier. But Michael loves film and fought for it, and they had the means. Eventually though, I ended up going in the other direction and working with Godspeed You! Black Emperor, which is all 16mm projectors on stacked tables, completely homegrown and organic and variable.

Bella Ciao (2018)

SFJ: Were you working with them from the beginning?

JC: No. I first heard Godspeed sitting in the office of Southern Records, 1997 or ’98, in London. I walk over to a stack of records and see this beautiful sleeve, and I’m like, “Wow, what is this?” I was waiting for a ride and put it on two or three times in a row.

SFJ: This was F♯A♯?

JC: Yeah. Then somebody I’d known from the avant-garde, New York theater world, who’d become friends with one of their guitarists, came up to me and said, “I just heard from my friend David that they’re looking for films,” and I was like, “I fucking love that band.” I heard they’d turned down licensing their music for some big corporate ad so I said, “I’ll give them films, I’ve got films.”

SFJ: What year would that have been?

JC: ’99, I think. I wrote them and said, “Hey, I’m a filmmaker, and I’ve got some 16 and I’d love to talk to you people.” They knew some of my work and were just like, “Well, we’re going to be in Baltimore and then DC, you want to come?” I walked in with a stack of cans that I thought I’d just leave with them, and they were like, “Oh, there’s the projectors. Go ahead.” I started projecting that night. They had a projectionist with them who was able to organize it, but I ended up running away on that tour. Left my car in a parking lot upstate, woke up a week later in Montreal. I contributed a lot of footage over the years, and still do, because they’re people I care a great deal about.

SFJ: You understand rhythm and silence in a way that someone who’s not musically inclined wouldn’t get.

JC: But filmmaking is rhythm. I’m ignorant about the actualities of notes and chords and such, but maybe what I share with some musicians is wanting to reinvent what those things could be, rather than just knowing what they are. You want to break things down, recombine, collage. Editing is making music with pictures.

SFJ: Your films are so gentle even when the subject isn’t. Somebody else would’ve made a film about Fugazi that was aligned with the guys in the pit. They would do all the clichés, you know, the same vibe as “Waiting Room” being used for football games. But there is so much stillness in your work. It is integral to your voice. At the end of Instrument, there’s that beautiful footage of Guy doing bunny hops, just his feet. And it’s such a gorgeous moment, but the audio is something else, not loud or aggressive.

JC: In “Shut the Door,” his dancing is incredible. The band had had it with violent mosh pits but totally loved for people to dance. I was more focused on people’s individualized movement, not the rituals that had become damaging clichés.

SFJ: And then you have the classic Guy-in-the-hoop moment.

JC: I didn’t shoot that, but I’m so glad we got to use it.

SFJ: Do we know which shorts Metrograph are going to play?

JC: A grab bag. Probably three with Jim White, the Elliott Smith, maybe some with Marc Ribot, and some surprises. Definitely Tree Song (2019) by Xylouris White, one of my favorites. We were doing this live gig together in Texas, one of these Gravity Hill shows, but on our last evening, when we were done, I was like, “Can we please just get out into the desert?” We raced out towards sunset, and I walked up a hill with my camera shooting the landscape. Jim and Giorgos were walking down the road talking. There was no plan; they didn’t even know I was filming. I was actually about to run out on the only camera card I had, and I yelled, “Turn around, turn around and walk back!” so they’d come back into the frame. I just barely caught it.

SFJ: You use unexpected moments well.

JC: Most cinema is based on control. If actors are talking in a restaurant, they often make everybody else in the background pretend to talk and then do a big, complicated ADR thing afterwards. And if they want rain, they bring in rain machines. Okay, this can be wonderful; it’s not a bad thing. But you can also let the world in and accept a higher degree of chance. That’s also totally inseparable from the economics of having little money. I don’t usually have a crew; I’d love to, sometimes. I often don’t have a producer; I love it when I do. So, it’s not like I’m making a dogmatic statement that this is the only way to go. But after doing it this long I’ve come to realize you lose and you gain; it’s a trade-off. I’m thinking of Opened Ending (2020), the music film I did for Jessica Moss, with a stolen shot of people on the subway. You can’t beat the random background hand gestures that you couldn’t ask an actor to do because they wouldn’t get it right and you wouldn’t be in a real subway car in the first place; you’d be on a subway set with a crew having to shake the pretend subway car. You can’t beat the real world. That’s rule number two.

SFJ: Wait, what was rule number one?

JC: I don’t know rule number one.

The Militant Ecologist (2018)

Share: