[wpbb post:terms_list taxonomy=’category’ html_list=’no’ separator=’, ‘ linked=’yes’]

[wpbb post:title]

Yvonne Rainer

[wpbb post:terms_list taxonomy=’category’ html_list=’no’ separator=’, ‘ linked=’yes’]

BY

[wpbb archive:acf type=’text’ name=’byline_author’]

On the life and work of legendary NYC artist Yvonne Rainer, through her own words.

Lives of Performers: The Films of Yvonne Rainer, a seven-film retrospective of Rainer’s newly restored films, screens at 7 Ludlow from Friday, February 17.

When Yvonne Rainer was a teenager, she “had no contact with boys,” and yet, when she joined her high school Writers’ Club in 1952, she submitted a “long prudish story about a boy who read too many comic books and ended up a juvenile delinquent. The teacher urged me to write about subjects more in keeping with my own experience.”

Although treated as an inconsequential aside in her 2006 memoir Feelings Are Facts, this advice appears to have resonated with the artist, who, working across performance, cinema, and literature, has exemplified the dictum write what you know to an extreme. Later in the book, she excerpts a 1961 diary entry: “I ape everybody; I am a human garbage dump-the garbage being bits and piece of movement seen and relished everyday of my life. I have faith in my garbage-disposal system. Everything that goes in, no matter how second-rate, will someday emerge in a personal, perhaps even original form.”

Compared to Rainer’s oeuvre-a portfolio that has at the very least changed the face of modern dance-Feelings Are Facts is straightforward, a narrative told almost chronologically, with the help of correspondence and notes from personal archives. It details a tumultuous childhood and adolescence in 1940s San Francisco, a move to New York at 21 with the painter Al Held, a marriage to and divorce from said painter in the late ’50s, cross-pollination with pioneering artists at the nascent Judson Theatre throughout the ’60s, receiving the first of two Guggenheim Fellowships in 1969, and becoming an internationally celebrated performance artist while confronting serious health issues, emergent political convictions, sexual frustrations, and bouts of depression.

FIlm About a Woman Who… (1974)

Because this is the story of Rainer’s life until her pivot to filmmaking around 1972-a good place to stop, the author explains, since her films are so memoir-like-it ends at the start of an incredibly influential auteur turn, only briefly mentioning a decade-long period of celibacy, and, at the age of 56, Rainer’s first lesbian relationship, with the academic Martha Gever, which has now lasted over 30 years. But although the memoir’s scope is “less than half the story,” she writes, “as more and more of my private life went into my films, such transposition, though fictionalized, reduced my need to reconfigure it elsewhere.” Or, the author muses in an epilogue, she could keep going, seeing as there is always more to tell, especially when we are talking about ourselves.

In fact, at 466 pages, the book does seem to stop short, in part because Rainer has applied and reappropriated much of the language that she developed during those earlier years to her films, splicing text from diaries with cinematographic tropes; historical research; collaborators’ and detractors’ observations; feminist, queer, postcolonial, and psychoanalytic theory; and slapstick comedy. At the end of the book, we’re just getting to when it all starts to gel. For more on that, though, Rainer reminds us, “two books on my films have already been published”-The Films of Yvonne Rainer (1989), and Essays, Interviews, Scripts (1999).

In her second feature, Film About a Woman Who… (1974), a caption, “They thought her shit was more important than she was,” appears over a scene in which two dancers move to silence. In this context, “her shit” could be understood to mean the performance, a minimalist work by the by-then acclaimed choreographer. Given the themes of the film, it could also easily mean “a woman’s” looks, her ambition, or her relationships with powerful men. But in Rainer’s memoir, the line is found in another context: part of a section on the anal retentiveness of Sunnyside, a foster home where the author lived between the ages of four and seven, only visited by her parents on weekends, after her mother experienced a form of mental breakdown:

You had to stand in line to take your turn on the toilet every morning after breakfast, and after you succeeded in moving your bowels Mrs. Howard or Miss Burlew would make an inspection. If you weren’t successful you received a tablespoonful of castor oil. They thought our shit was more important than we were.

A voiceover cuts in during the aforementioned scene in Film About a Woman Who… with Rainer herself reading aloud: “This is the poetically licensed story of a woman who finds it difficult to reconcile certain external facts.” Rainer’s multidisciplinary work might be boiled down to something like reconciling certain external facts, or interpretating the immediate. Her most famous performances are careful arrangements of undancerly steps, done in street clothes and tennis shoes. Like narrativizing one’s own life as an analysand, the revaluation of banal gestures as dance steps tends to shuffle their meanings, perhaps surfacing new and latent associations.

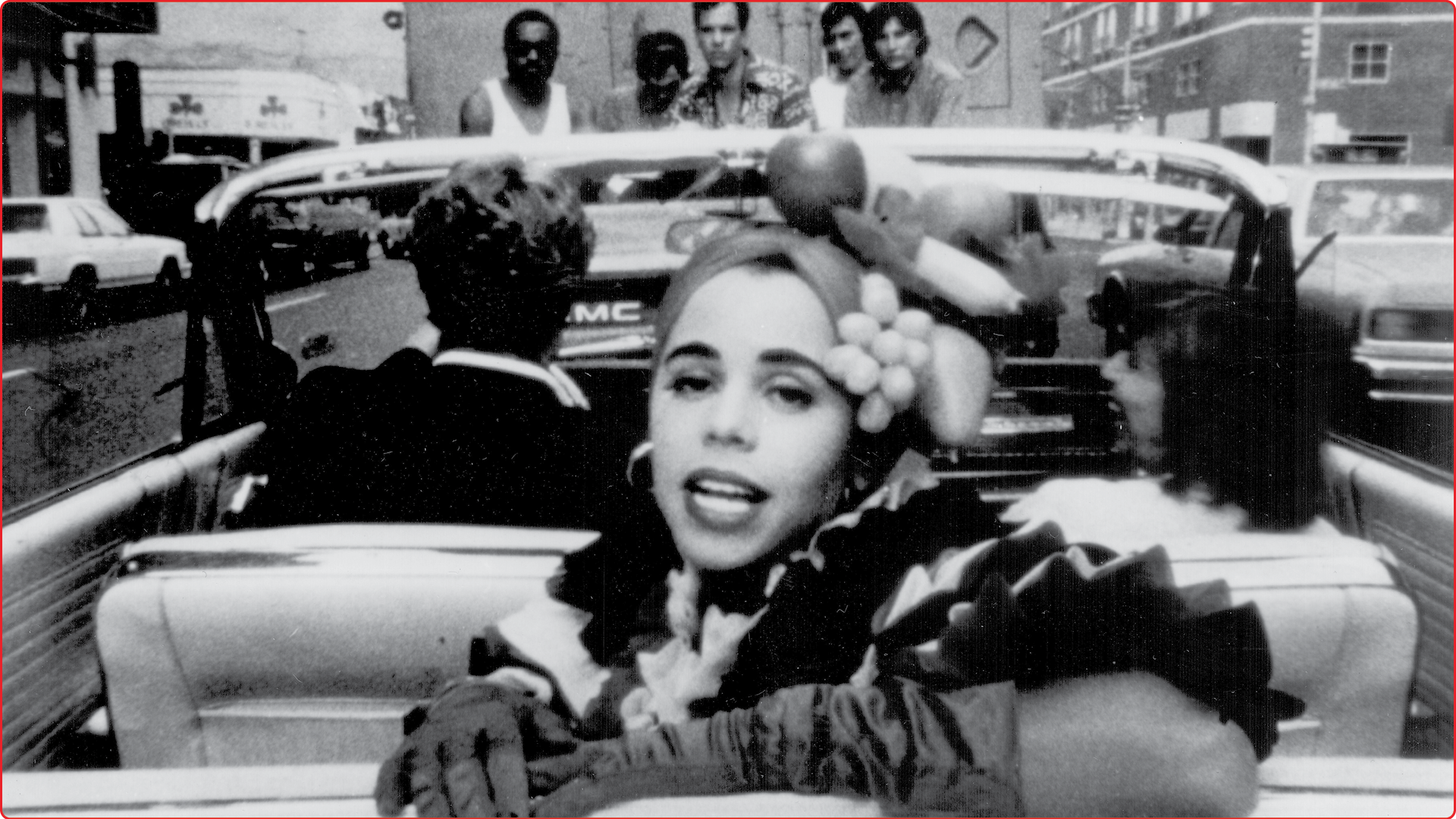

Lives of Performers (1972)

If Rainer’s first few decades of art practice were about collecting and working through experiences-examples of her “garbage disposal-system” might include Ordinary Dance (1962), which featured a monologue listing streets on which she had lived; Trio A (1966), which deliberately executed evenly distributed as opposed to expressive dance phrasing, echoing non-dance behaviors; and the employment, in several performances, of objects charged with intimate meanings, like mattresses-the next few were about refracting these experiences through the more “specific” medium of text and narrative. The films “grapple with the challenge of representing and fictionalizing the inferno of my own passions,” or, as written in a 1990 artist’s statement, “My films can be described as autobiographical fictions, untrue confessions, undermined narratives, mined documentaries, unscholarly dissertations, dialogic entertainments.”

By contrast, Feelings Are Facts tries its best to be exceedingly truthful, a nonfiction, even if its title appears to suggest otherwise. As it turns out, “feelings are facts” is one of Rainer’s mantras, a reminder that emotions are allowed into her story-are, in some ways, the whole story. In the memoir’s second-to-last chapter, she tells us where she first heard the phrase: in analysis, where statements like this are usually made to coax deeper associations from a patient. For Rainer, though, the words resonated as a slogan protesting the era’s pervasive mindset. “‘Feelings are facts,’ an adage of the late John Schimel, my psychotherapist in the early 1960s, became an unspoken premise by means of which I was able to bypass the then current clichés of categorization popularized by [media theorist Marshall] McLuhan.” In midcentury America, and particularly in the worlds Rainer inhabited-she was working with and around luminaries of the Fluxus and Neo-Dada movements who were intent on breaking with the more sentimental aspects of art by focusing on process, commonplace occurrence, and improvisation-feelings might easily be suppressed in service of so-called anti-art practices.

Ignored or denied in the work of my 1960s peers, the nuts and bolts of emotional life shaped the unseen (or should I say ‘unseemly’?) underbelly of high U.S. Minimalism. While we aspired to the lofty and cerebral plane of a quotidian materiality, our unconscious lives unraveled with an intensity and melodrama that inversely matched their absence in the boxes, beams, jogging, and standing still of our austere sculptural and choreographic creations.

Hence, Rainer began inserting the most personal of memories into her work, an impulse she has lived with since childhood, and one she investigates in Feelings Are Facts:

I was the outsider, the scapegoat, the compensatory clown, the object of ridicule, and the one who supplied her tormentors with the weapons of her own destruction. I told them I had been born in the toilet; I told them I didn’t believe in God; I told them we were anarchists and my parents had been vegetarians; I told them my father was a World War I draft dodger.

Privilege (1990)

It is this same impulse, Rainer surmises, that must be responsible for the writing of this memoir: “I am still a little uneasy about my motives. Why do I seek to make myself known when I have already accomplished this in performance and film? Do I wish to make claims to a hearing and in so doing seek, in [literary theorist] Peter Brooks’s words, ‘a catharsis of confession?'” No, she argues in a prologue, “I prefer to think of this enterprise as a more guilt-free kind of testimony: to a life, to the products of that life, and to its public and private interplay.” Yet later, Rainer finds fault in her own argument while ruminating on the time she told Held that she had cheated on him: “What that confession points to is my long standing mania for ‘telling.’ … I live with a weird compulsion to betray myself, to reveal everything, under the guise of a disingenuous ‘openness.’ Ha! And now I find myself entangled in Peter Brooks’s ‘catharsis of confession,’ which I so nobly disavowed in the prologue to this memoir.”

We are reminded that this text is controlled by its negative space, that this is the story of someone who has spent her life attempting to “reconcile certain external facts,” as, perhaps, all stories are. Rainer is continuously searching for some invisible architecture, reasons we might move or behave in the way we do, why a thing is funny to some people, frightening to others. She is increasingly fascinated by cliché and melodrama, especially after rejecting certain “feelings-however factual” as “stereotyped expression,” and refers to the words of literary critic Leo Bersani: “Cliché is, in a sense, the purest art of intelligibility; it tempts us with the possibility of enclosing life within beautifully inalterable formulas, of obscuring the arbitrary nature of imagination with an appearance of necessity.”

This quote is slide-projected during her performance Inner Appearances, and it appears on a card in her directorial debut feature Lives of Performers (both 1972). It comes from an introduction to the 1959 Lowell Bair translation of Madame Bovary-as classic a modernist work as we have, but one that speaks to many a postmodernist; Roland Barthes cites Flaubert’s use of the banal in fiction to explain his concept of “The Reality Effect.” Although Rainer doesn’t mention reading Madame Bovary in her memoir, it makes sense that this novel, or at least Bersani’s take on it, could possibly have set the artist (a child of immigrant anarchists; a student/collaborator of staunch avant-gardists like Merce Cunningham, John Cage, and Robert Rauschenberg) on a new path. With the unrealistic Emma Bovary’s futile attempts at escaping provincial life through emotional affairs and luxuries bought on credit, Flaubert’s novel “is certainly mocking literary clichés of romance,” writes Bersani, “but nothing in any of his works suggests that so-called great art can provide more accurate images of reality.”

Rainer is continuously searching for some invisible architecture, reasons we might move or behave in the way we do, why a thing is funny to some people, frightening to others.

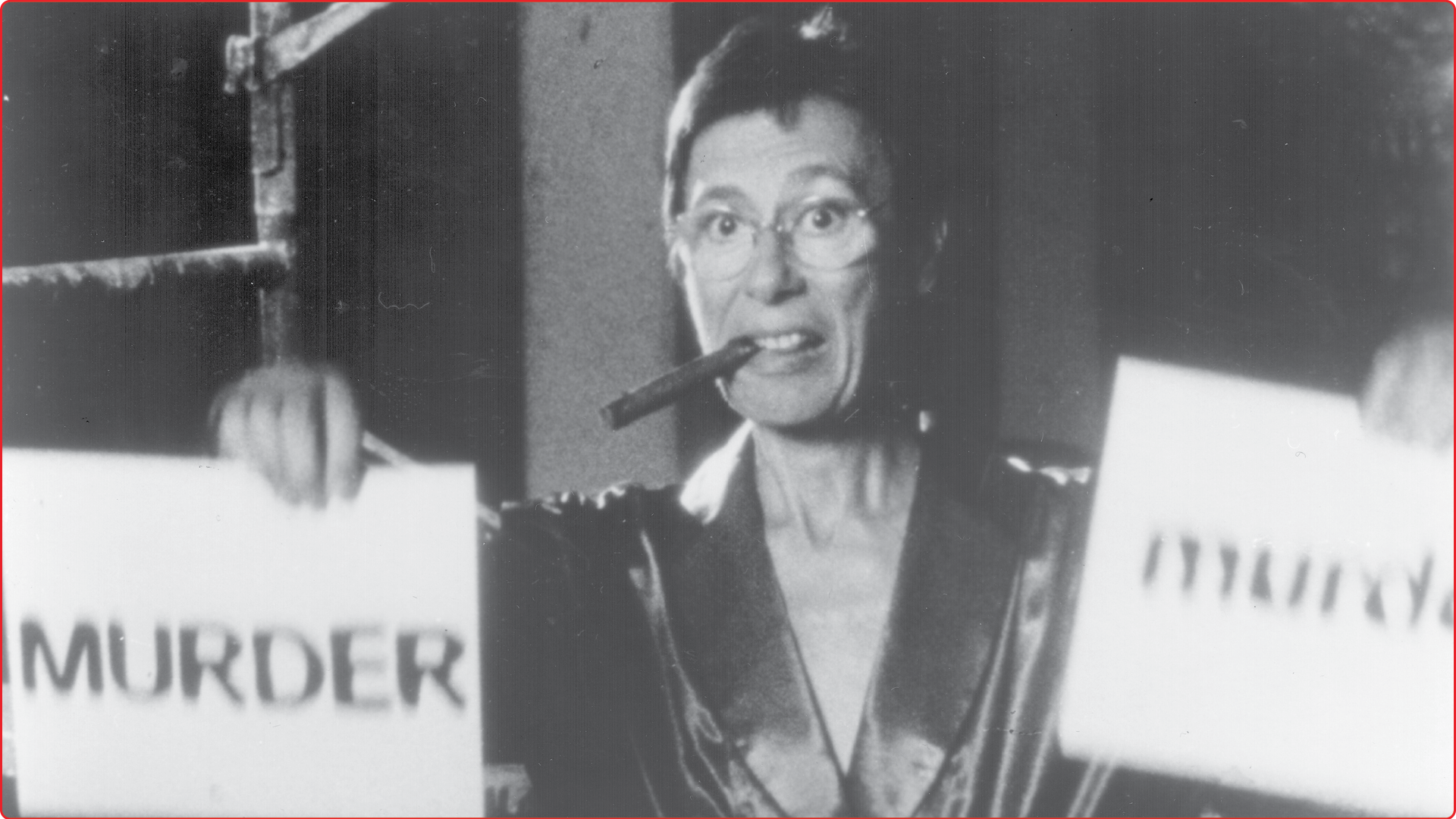

Rainer’s feature films purposefully teeter between critique and pastiche, leveraging cliché as base to life’s acid. They are peopled with well-worn archetypes that happen to be real: a noir-esque Assistant District Attorney character who steers the plot of Privilege (1990) is based on a man Rainer dated in 1961 (about whom her therapist at the time commented, “I thought you’d be the last person to get involved with a member of the bourgeoisie”). In her film, the DA’s room is striped with the shadows of slatted blinds; his car is a shark-like convertible. A Puerto Rican character, based on a real neighbor of Rainer’s, dresses up as Carmen Miranda and monologues about her white neighbor’s blind spots when it comes to race and class. In MURDER and murder (1996), a tuxedo-clad Rainer attempts to right a persistently toppling shopping cart, Chaplin-like, a look of true anguish on her face. A voiceover lists side effects of the medication she was prescribed following a breast cancer diagnosis and mastectomy.

In one of the last chapters of Feelings Are Facts, Rainer describes a particularly miserable period for herself in the early ’70s, during which she attempted suicide by swallowing four vials of sleeping pills with a slice of banana cream pie. Even here, an initial hesitancy in using “clichéd” emotions hovers over the page. The author searches for the strings that pull a person toward her own actions (“Under a cloud of depression, does one decide to commit suicide or is one driven to it?”) but allows herself the space to question this line of questioning, too: “What else underlies the questions we ask of Marilyn Monroe’s death? Was it an accident that she died? Did she really mean to do it? Or did she just want a little relief from the loneliness of that Saturday night? Would we respect her more if she had marched into oblivion resolute and determined?”

In tangents like this, the inadequacy of writing something like a candid memoir is underlined by its own text. If everything is to be reinterpreted forever-if feelings are indeed facts and vice versa-why bother? But, seen another way, why not try telling the story using the simplest terms, seeing as nothing is truly so simple? Sometimes, what is meant by “shit” is shit, which doesn’t quite uncomplicate the statement. “In hindsight,” writes Rainer, “if I ruminated at all over Dr. Schimel’s ‘feelings are facts,’ it would have seemed unassailably obvious that facts are best conveyed by writing.”

Natasha Stagg is the author of Surveys: A Novel (2016) and Sleeveless: Fashion, Image, Media, New York 2011 – 2019 (2019).

Yvonne Rainer’s Feelings are Facts is available for purchase from the Metrograph Bookstore.

MURDER and murder (1996)