Columns

Futures and Pasts: German Chainsaw Massacre

In Futures and Pasts, Metrograph’s Editor-at-Large Nick Pinkerton highlights screenings of particular note taking place at the Metrograph theater. For the latest entry, he considers Christoph Schlingensief’s rampaging reunification-themed splatter comedy.

Share:

t is something of a received truth that the filmmaking apparatus moves too slowly to respond to contemporary events as they happen, at least since the days when Dziga Vertov’s film-car followed the front of the Russian Civil War—but in fact this is only true of the models that require waiting patiently for signoffs from the front office and grant approvals; free of such obstacles, cinema can strike at the present with blitzkrieg speed. Case in point: Christoph Schlingensief’s Das deutsche Kettensägenmassaker (The German Chainsaw Massacre), shot in 10 days in mid-April 1990 in response to the imminent dissolution of the communist German Democratic Republic and the integration (or, if you prefer, annexation) of its federated states into the democratic and capitalist Federal Republic of Germany, made official on October 3 of the same year. On November 9, the borders between the GDR and FRG were opened; on the 24th of that month, The German Chainsaw Massacre played for its first audiences in a now-unified Bundesrepublik Deutschland, exorcised of the specter that once haunted Europe, at the 24th edition of the Hof International Film Festival in Bavaria.

Schlingensief’s film, as its title makes perfectly clear, draws heavily on both Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and its 1986 sequel. This debt is reflected in elements of Schlingensief’s storyline; in its careening, relentless, rabid-dog energy; and in the rough and ready, bare-bones circumstances of its production: the pittance of a budget for The German Chainsaw Massacre was reported as 160,000 Deutschmarks, then roughly equivalent to $90,000, a little less than $200,000 today when adjusted for inflation. Before settling into something resembling linear storytelling, Schlingensief’s film opens, discombobulatingly, with an in medias res scene of comic carnage sandwiched between footage of two televised demonstrations—the celebratory scene of the reunification ceremony staged in the shadow of Berlin’s Reichstag building, led by Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker and chancellor Helmut Kohl; and a North Korean float parade—along with, for good measure, a rather ominous series of intertitles thrown into the mix: “Since the borders were opened on November 9, 1989, hundreds of thousands of GDR citizens have left their old homeland. Many of them live among us unrecognized today. Four percent never arrived…”

We encounter one of those refugees-to-be, Leipziger Clara (Karina Fallenstein), being berated by her loutish lumpenprole husband, played by actress Susanne Bredehöft in drag, wearing a shoe polish smear of five o’clock-shadow and nonchalantly pissing in the bathtub as he swaggers into their shared flat. Clara, having evidently had quite enough of her “Ossi” (East German) partner’s boorish brutality, initiates a divorce by way of kitchen knife, after which she hops in the family car—a Trabi, the signature automobile of East German Orcar, manufactured by VEB Sachsenring Automobilwerke Zwickau until 1991—and lights out to the West for a rendezvous with her lover, the cleaned-and-pressed Artur (Artur Albrecht). Clara and Artur are reunited in a disused ironworks (a former Thyssen plant in Duisburg-Meiderich, where most of the film’s action takes place) in the Ruhrpott, the industrial heart of West Germany, about 10 miles from Schlingensief’s hometown of Oberhausen. There, against this backdrop of desuetude and desolation, incurable romantic Artur attempts to welcome Clara to her new life by ravaging her on a soiled mattress set aside for the occasion—a union interrupted by the appearance of a gibbering halfwit in a yellow rain slicker, who gleefully caves Artur’s skull in with a rock.

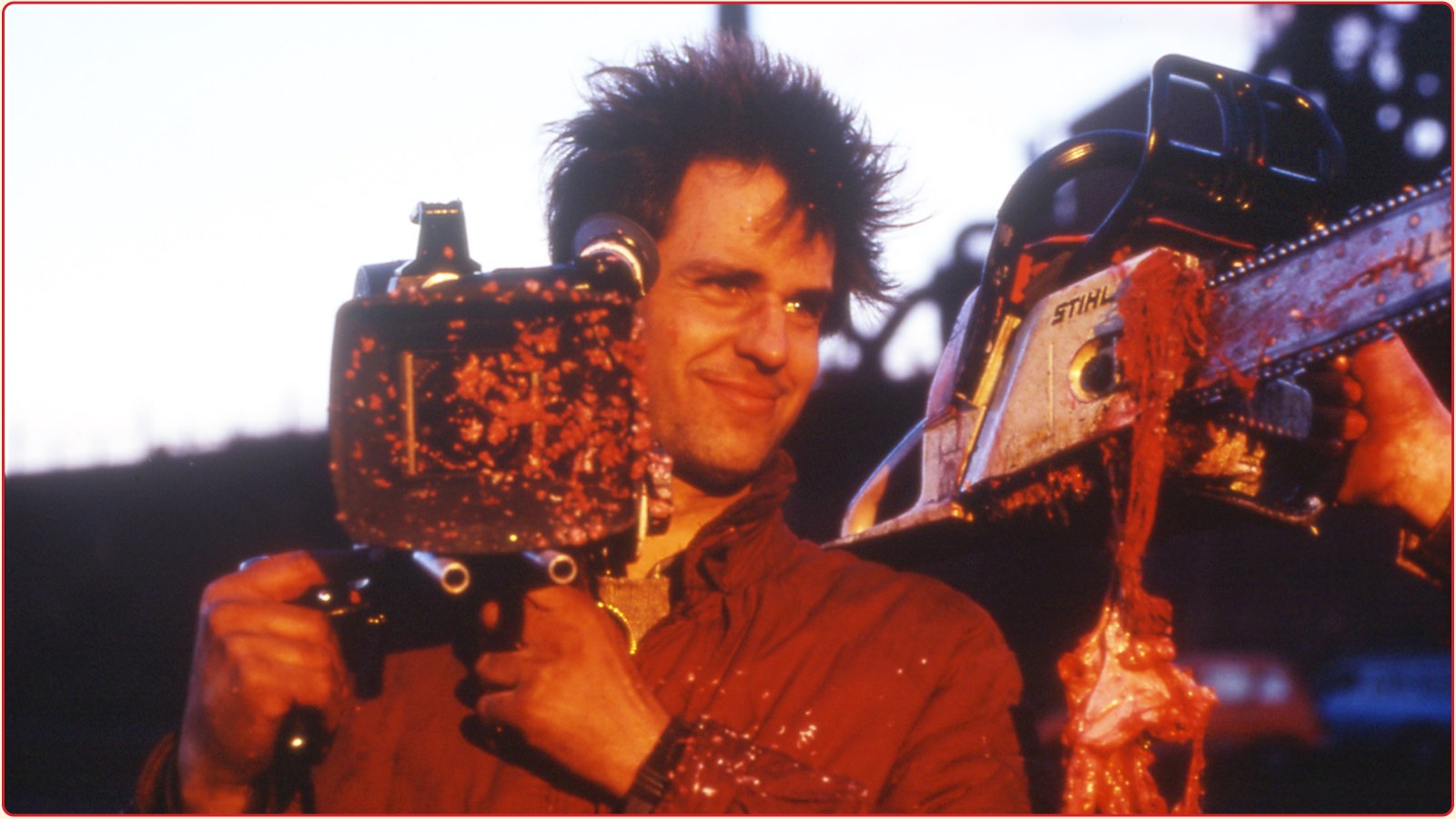

The German Chainsaw Massacre (1990)

It transpires that this maniac, Hank (Volker Spengler, star of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1978 In a Year of Thirteen Moons), belongs to an incestuous family of entrepreneurial “Wessis” (West German) meat-packers who make their home in the industrial wreckage, ambushing passing travelers and grinding them into Wurst for either sale or home consumption. (Why the road to freedom should pass through this dilapidated manufacturing backwater is never addressed, much less explained.) Playing the role of the family’s reclusive patriarch—in fact a skeleton fitted with a WWII-vintage combat helmet who appears to have been deceased since the Adenauer Era—the ringleader and eldest of the eternally bickering clan, Alfred (Alfred Edel), issues “commands” in a piping soprano from behind a closed office door, à la Norman’s ventriloquism of the late Mrs. Bates in Psycho (1960): berating his daughters, Brigitte (Brigitte Kausch) and Margit (Bredehöft, resurrected as a predatory butch lesbian); stepbrother, Dietrich (Dietrich Kuhlbrodt); Hank, the verboten offspring of Dietrich and Brigitte; and Jonny (Udo Kier), the poodle-haired product of another incestuous coupling between Alfred and Margit, who swans about in what I believe to be a Wehrmacht uniform and makes a nuisance of himself at Café Porsche, the roadside bar operated by Kurti (Reginald Schnell), who may or may not be a blood relation to the murderous tribe. (If I’m being perfectly frank, after multiple viewings none of these family relations have entirely become clear.)

In Jonny’s first scene—discounting an earlier nightmare sequence in which Kier appears with a swastika drawn onto his philtrum, like an Adolf stache, hectoring Clara—he rolls into the café, gacked up on God knows what, and, giggling giddily, first sets his blonde perm on fire then, for no apparent reason, hacks off his right hand with a meat cleaver and graffitis a peace sign on the wall, using the gore that spurts from the stump of his wrist as ink. This should give some sense of the narrative logic, such as it is, that drives The German Chainsaw Massacre.

In the midst of such outbursts of inexplicable self-harm, others strive to keep what’s left of their bodies intact. Clara and Artur—the latter with his face pounded into goo, but still, somehow, ambulatory—spend the remainder of the film individually endeavoring to outrun and outwit their persecutors, who fishtail around the grounds in a revved up Mercedes-Benz convertible, scouring the shell of the factory for prey they’ve already caught, captured, and momentarily incapacitated, then proven too addled and argumentative to hold on to. Much bloodshed ensues, none of it particularly convincing, nor intended to be. Brains are dashed out with a “lead pipe” that closely resembles a wrapping paper cardboard tube spraypainted silver, what appear to be Styrofoam packing peanuts gush from a spinal column ruptured by a chainsaw, and, after Brigitte has her lower extremities snipped off in an auto accident, she remains lucid for a remarkably long time, Kausch barking her agonized line readings (“Thoughts are free, who knows what they will be?”) while clearly buried to just above her navel in the dirt, her torso perched atop a gore-glossy heap of butcher’s offal.

No attempt is made to disguise the bargain basement nature of the production, which leads to some interesting inventions: slow-motion sequences, for example, appear to have been created in post-production by filming existing footage being cranked frame by frame on the playback screen of a flatbed editing table. The most indelible effects, though, come via the actors, whose unanimously hyperactive performances occupy a range that runs from obnoxious speed-freak jabbering to extremely obnoxious speed-freak jabbering, with Kausch, who flits effortlessly between taunting, skipping little-girlish singsong and grunting guttural freakouts, a particularly memorable masticator of scenery. A more exquisite gallery of cruel peasant physiognomies is difficult to imagine: Edel, a veteran of films by Werner Herzog and Straub-Huillet whom Schlingensief had first worked with on 1984’s Tunguska – Die Kisten sind da, has a mug that looks like it’s squished against the glass of a specimen jar; the bald-pated, shell-suited, brick-complexioned Kuhlbrodt has the air of an alcoholic junior high PE instructor with a penchant for spousal abuse, though he was in fact employed as a full-time public prosecutor in Hamburg. (“A prosecutor digging around in intestines with a chainsaw,” said Schlingensief of the casting, “That’s crazy, isn’t it?”)

The German Chainsaw Massacre (1990)

In attempting to describe the particular place in German culture occupied by the director of The German Chainsaw Massacre from the late 1980s to his death at age 49 in 2010, it would come near enough the mark to call Schlingensief an inheritor to the mantle of Fassbinder: an astonishingly prolific multihyphenate artist (films, television, live theater, opera, performance), enfant terrible, public shit stirrer, ruthless critic of German social and political institutions, and unifier of pop and high modernist traditions who, moreover, made frequent use of the Fassbinder repertory in his films. (Along with Spengler and Kier, Irm Hermann appears in Chainsaw as a newly unemployed—but still brassy and bossy—Volkspolizei guard at the West German border, while his 1992 Terror 2000 – Intensivstation Deutschland gives a starring role to Margit Carstensen.) The comparison is near enough the mark in some ways, misleading in others: in the sustained hysteria of the performances in his films, Schlingensief is closer to the Fassbinder of the frenzied, Artaud-influenced Satansbraten (1976), an extreme outlier in his filmography, than to the narcotized, pared-down acting largely favored by R.W.F., and Schlingensief’s headlong, thick-of-the-scrum cinematography resembles nothing in the Fassbinder catalog. (A more useful analog here is gonzo Japanese filmmaker Gakuryū Ishii, who in fact had been to West Germany a few years earlier to make 1986’s Halber Mensch with Einstürzende Neubauten, so who knows…)

Curator Anna-Catharina Gebbers, describing the singular screechy Sturm und Drang of the Schlingensief style, writes that he “rejected the type of continuity meant to suggest realism in commercial films. Instead, he strung together series of dissonant images. He moreover heightened the sense of nervousness through the use of a handheld camera and a handheld spotlight whose tempo competed with that of the camera, as well as through a drastic, violent quality and comic-strip like reduction of the figures and story lines—neither of which developed, since no ’acting’ in the conventional sense was permitted to take place.”

The sprinting camerawork in Chainsaw—and its herky-jerky, playing catch-up focus-pulling—are Schlingensief’s own, having added DP and camera operator to his credits after his film’s original cinematographer jumped ship. The crude, shaggy, and baggy qualities of Chainsaw, though, are by no means marks of inexperience. Born in 1960, Schliegensief, had made his first 8mm short while still in primary school; by 15, per acquaintance Klaus Biesenbach, “he used a helicopter and had a freeway temporarily shut down” for a shoot. On his unusually detailed IMDb page, one can find entries for juvenilia including 1973’s Das Totenhaus der Lady Florence (Lady Florence’s House of the Dead) and 1975’s Rex, der unbekannte Mörder von London (Rex, the Unknown London Murderer), titles that suggest an early affinity for the macabre.

He began as an amateur filmmaker, and an amateur filmmaker he in some sense would remain. Schlingensief, like Fassbinder, applied for admission to film school—the University of Television and Film Munich, where Schlingensief had relocated—and like Fassbinder was rejected, leaving him to create a canon of his own, made up in significant part of figures without academia’s stamp of approval. (The experimental filmmaker Werner Nekes, for whom Schlingensief worked as an assistant, was an important mentor.) Where Fassbinder’s cinema would be deeply affected by his encounter with Douglas Sirk’s Hollywood melodramas, Schlingensief was shaped by other masters: Luis Buñuel, Kenneth Anger, Werner Schroeter, Monika Treut, and, most relevant here, American grindhouse cinema. In addition to Hooper, he professed his admiration for Russ Meyer, while the Thyssen steelworks in Chainsaw—and Bredehöft’s sneering bull dyke—recall the shantytown Mortville of John Waters’s Desperate Living (1977) and particularly Lowe’s Mole McHenry in that film. While Schlingensief may have gone on to attain a tenuous place in the narrative of German Kultur as court jester and pain-in-the-ass, his Chainsaw belongs to a particularly Teutonic strain of schlock that was reaching a flower of putrescence around the time of its release, which includes the films of Jörg Buttgereit, and more esoteric fare like Andreas Schnaas’s Zombie ’90: Extreme Pestilence (1991) and Patrick Hollmann and Sebastian Panneck’s Urban Scumbags vs. Countryside Zombies (1992).

The German Chainsaw Massacre (1990)

If The German Chainsaw Massacre enjoys a claim to social relevance that’s rarely made for the above-named works, it comes through its author’s future accomplishments in more esteemed fields of cultural production—Buttgereit never staged Wagner’s Parsifal with Pierre Boulez at Bayreuth, as Schlingensief would do in 2004, though we are perhaps the poorer for this, nor did he prepare the German Pavilion for the Venice Biennale in 2011—and the fact that the film puts trash horror tropes to metaphorical use. To anyone who has suffered through the artfully affected airs of 21st-century “elevated horror,” this is not necessarily an endorsement, nor the fact that Chainsaw is the second entry in what its author gave the rather highfalutin title of the “Germany Trilogy,” preceded by 1989’s 100 Jahre Adolf Hitler – Die letzte Stunde im Führerbunker (100 Years of Adolf Hitler: The Last Hour in the Führerbunker) and followed by Terror 2000.

The title of the trilogy seems forbiddingly pretentious, but Schlingensief intent is to lampoon the pretentions of contemporary German “art” cinema: 100 Years of Adolf Hitler opens, sneeringly, with footage of Wim Wenders—who, after 10 minutes, had stormed out of a screening of Schlingensief’s Menu Total (1985) at the Berlinale—collecting the Best Director Award two years later at the 40th Cannes Film Festival for Wings of Desire, and Laurence Kardish has written of the trilogy as a whole as Schlingensief’s “concise riposte to Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Hitler, ein Film aus Deutschland (1977),” a 442-minute exegesis of the historical truth (and mythical afterlife) of its subject that Susan Sontag proclaimed a Masterpiece. Schlingensief was a filmmaker averse to the embalming qualities of the “M-word,” and in his work you will find nothing reflecting Wenders’s noble claim at the rostrum, “We can improve the pictures of this world, and with that this world can be improved,” nor any of the clamoring for midwit respectability that abounds in the contemporary horror-as-metaphor industry. These are proudly and sometimes profoundly stupid movies, and in their very dunderheadedness, their deliberate shabbiness and uncorrected “mistakes,” one can find a perspective on German history that goes far deeper than undergraduate literary tropes, an approach in which ideas are inextricable from style.

Recently, a friend who was reading Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem memorably reported his takeaway from the book regarding the top brass of the National Socialist Party—“It’s just unbelievable how stupid those motherfuckers were!”—and this is something like the abiding theme of 100 Years of Adolf Hitler, in which der Führer, Göring, and associates (the two named played by Kier and Edel), bouncing off the bunker walls while awaiting the Red Army’s arrival, are portrayed as a pack of yammering, thoroughly debased cretins. The imbecility of evil, rather than its banality, is likewise very much on display in The German Chainsaw Massacre.

The “message” of Schlingensief’s film, as Orson Welles said of most movie messages, could be written on the head of a pin: that German unification, far from being the merger of two states, was the cannibalistic consumption of one by the other, and that, per a contemporary reviewer in the left-wing daily Die Tageszeitung, the “Ossis” were being “slaughtered for unification” by the “Wessis” symbolically and, in Schlingensief’s film, quite literally. A simple enough concept, delivered with blunt force and an urgency that reflects the urgency with which the film was conceived, made, and brought to completion—but to take that message for the whole essence of The German Chainsaw Massacre, rather than the maelstrom of aggressively puerile, braying idiocy that unfolds in its one-hour runtime, is to miss the point entirely. I suspect that, in Schlingensief’s thinking, to apply excessively nuanced analysis to developments in the political sphere that were not, in fact, the result of particularly nuanced minds—be the year 1945 or 1990—would be to lend these developments a dignity of which they were unworthy. Subtlety was, perhaps, not Schlingensief’s strong suit—he was jailed briefly in 1999 for appearing at a performance at documenta X in Kassel for carrying a placard reading “Kill Helmut Kohl!”—but subtlety is not all. And so, The German Chainsaw Massacre: a hasty, slapdash, febrile film for a hasty, slapdash, febrile time, as the leaders of a new Germany flung it heedlessly into a global community in which unfettered ravening capitalism would be law of the land, of all lands; an imbecilic film for a culture steeped in imbecility, a world governed by imbeciles. Against stupidity, as Schiller would have it, the Gods themselves contend in vain. As his gesture of protest, Schlingensief offers us giddy, gibbering surrender.

The German Chainsaw Massacre (1990)

Share: