Columns

Cracked Actor: Steve Buscemi

On three of the beloved actor’s most squirmy performances.

Three Starring Steve Buscemi is streaming now on Metrograph At Home.

Share:

Steve Buscemi often plays the trickster: the aggrieved huckster, the jack-of-all-trades struggling to make it work through zany gig after gig. On screen, he’s a hustler. Best known as a quirky character actor, Buscemi has frequently played offbeat criminals or smarmy conmen in his collaborations with directors Quentin Tarantino—Reservoir Dogs (1992), Pulp Fiction (1994)—the Coen Brothers—Barton Fink (1991), Fargo (1996), The Big Lebowski (1998)—and Jim Jarmsuch—Mystery Train (1989), Coffee and Cigarettes (2003), and The Dead Don’t Die (2019). He built his career on memorable turns in cult classics such as Parting Glances (1986), King of New York (1990), and Ghost World (2001), a performance that earned him his first Golden Globe nomination. In fact, Buscemi has always been a distinguished physical actor, although in his films he often appears to be the butt of the joke. In Ghost World, he shuffles around with his hands in his pockets, looking down even as the teenage Thora Birch tries to flirt with him, smoothing over his hair with shaky fingers and turning over a record. His little tics and nasally syllables offer their own madcap production. Hunched over with his hands clenching his back, he delivers a weary scowl. Eyebrows raised, he squares his shoulders and shimmies. There’s a range of promiscuous physicality that reveals the troubled labor that goes into his whimsical acting.

Buscemi has made a habit of playing characters who cycle through the kinds of jobs one finds advertised on Craigslist (he even cameos as a mugger on Broad City, the most optimistic show about the freelance economy). The underprivileged must be chameleons. Shapeshifters, jokers, clowns, and savants. Adaptable without frailty, heard without being shrill. The clown rises from the bottom to the top and falls once again. How many balls can he juggle? A job is a job is a job. Buscemi zeroes in on the minutiae of annoyance. Can’t anyone give him a break? By now he’s gained enough of a name that he’s even appeared as himself. In a now iconic episode, he infiltrates a school on 30 Rock and asks, “How do you do, fellow kids?” Diving headfirst into a new environment is where he thrives, even when he misses the mark or skirts the landing. This is the general crux of Buscemi’s cinematic hijinks: he’s always ready for the next side hustle, usually landing on his feet.

The lupine hunger Buscemi so instinctively embodies is on its richest display in a string of meta-movies about the pangs of show business that are currently streaming on Metrograph. He’s a down-and-out screenwriter in In The Soup (1992). Living in Oblivion (1995) finds him a beleaguered director who can’t keep his crew on track. Delirious (2006) plunges him into the sleazy world of the paparazzi. The industry is a vicious confrontation between creativity and career, the rich and the poor, ambition and sacrifice. No one comes out unscathed; no one is free from thankless labor.

In the Soup (1992)

In Alexandre Rockwell’s wry black-and-white comedy In The Soup, Buscemi’s Adolpho Rollo is forced to turn to a charismatic gangster (played by Seymour Cassel) to help finance his script, only to discover that he must wheedle, beg, and steal from naive neighbors. (Jarmsuch and Carol Kane have small roles as the directors of a porn-for-quick-cash scheme.) Adolpho is a meek man, quick to submit in the presence of stronger personalities. He wants to peddle his script, but the 500-page tome about Nietzsche and Dostoevsky is hardly marketable. The film he wants to make is in black and white, and draws on Godard and Tarkovsky, much like In The Soup itself. In the end, Adolpho wonders if it would be better just to make a film about himself. It’s a movie about big breaks slipping through your fingers, about finding an alternative masculinity to the aggro grandeur of the mob world (à la the HBO series Boardwalk Empire of which Buscemi was the star).

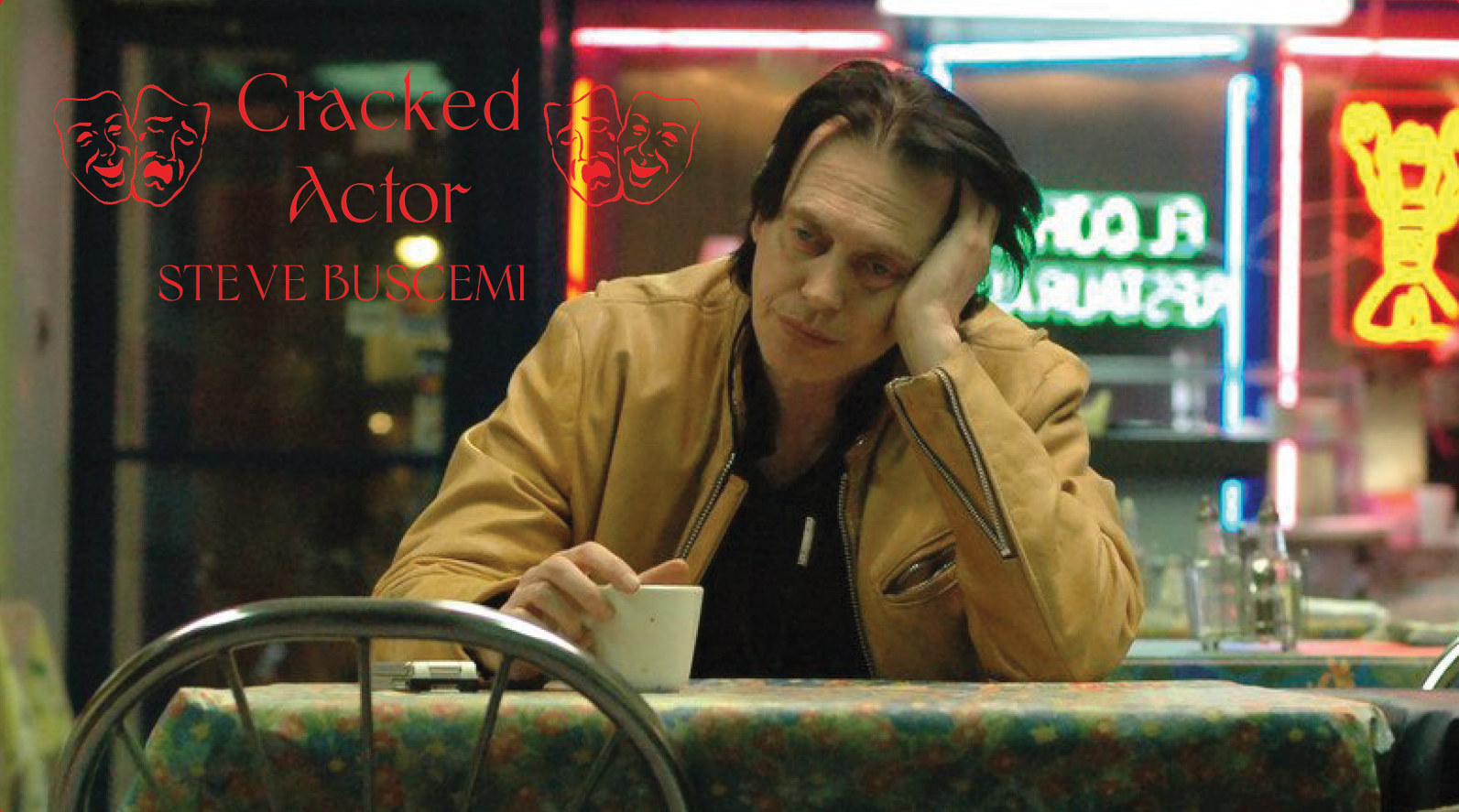

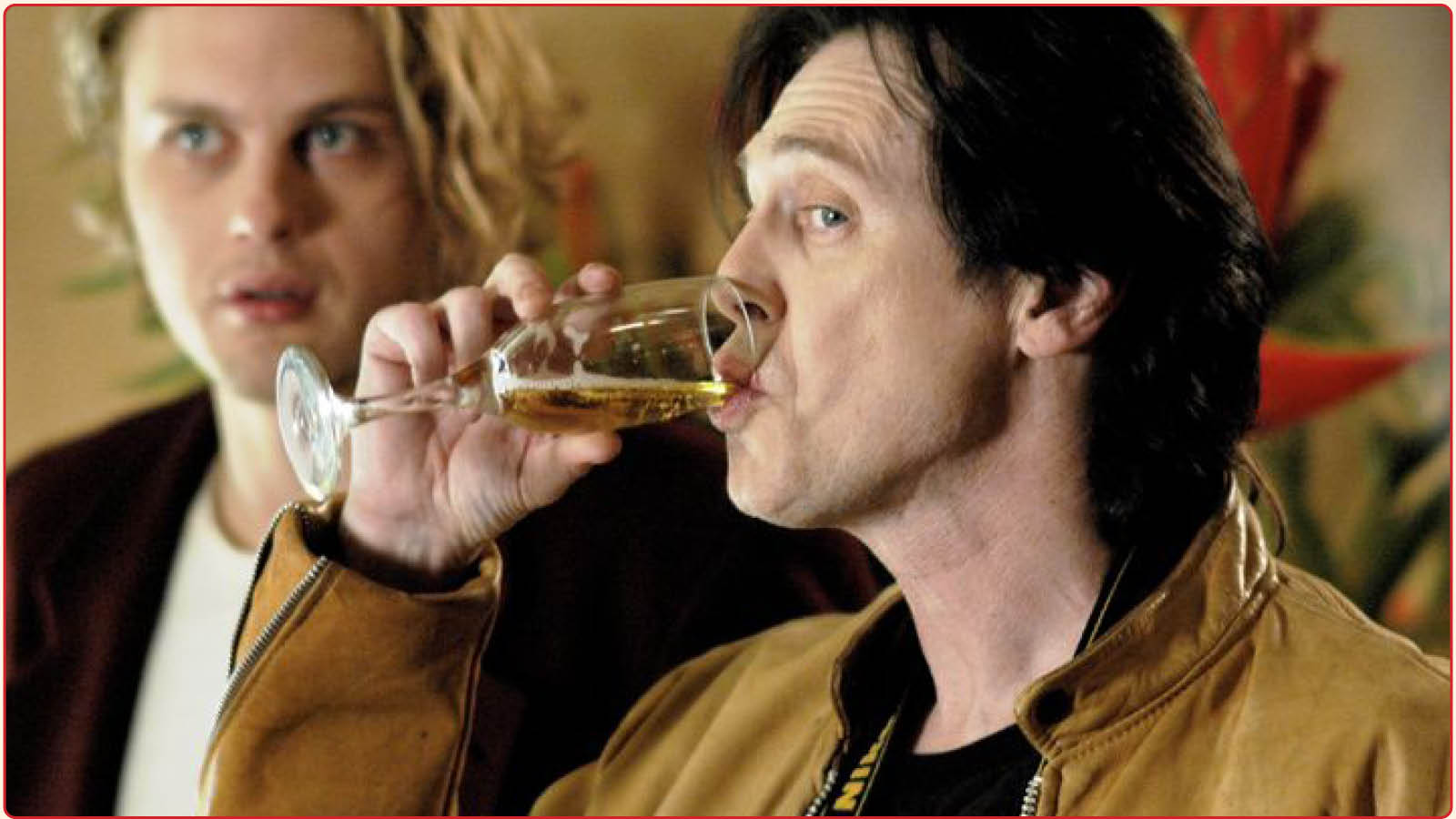

In the grim sepia-toned streets of Tom DiCillo’s Delirious, Buscemi’s anxious paparazzo Les Galantine tries to teach his young, homeless protégé Toby Grace (played by his future Boardwalk Empire co-star Michael Pitt) that labor is always extractive, whether done by scum or celebrity. Down in the gutter, a close-up of a dying flea stands in for Les’s sinking ambition and parasitic impulses. Always ready for the next scheme, it’s been a long time since he got a money shot worth getting excited over. But his professional striving strangles his personal life; Toby seems to be his only close friend and Les struggles to garner the approval of his strict parents due to his less-than-reputable career choice. He’s bitter over his continual losses, disconnected from any larger community. Photography is his only zone of physical mastery.

He’s frustrated more than fruitful in his endeavors—he screams, easily reaching a fever pitch over the small annoyances of life. As in the Jarmusch films Buscemi is so fond of, cigarettes and coffee play a big role here, too. Real drinks are a sign of making it. When Toby surpasses Les by dating a beautiful popstar K’harma (Allison Lohman), he becomes something of a celebrity himself, reaching for martinis, rather than shitty bodega coffee, when exiting the shower. There’s time for leisure when one isn’t snatching up any job that comes your way. It’s a long way from the times the pair used to steal as many free after-party goody bags as they could handle.

If Toby’s earnestness allows him to triumph without much effort, Buscemi as Les is a pessimistic rat snacking on leftovers. The film knows this, juxtaposing a shot of Toby getting the girl—when K’harma whisks him into a party—with a rattled, abandoned Les working his way through a turbulent red carpet as the scrambled voices of photographers and thronging fans crowd his thoughts. When the chance comes to betray Toby, Les is all too willing to get the shot, whatever the cost, in no small part driven by his own sense of vengeance after Toby jilted him to cozy up to K’harma. In the final scene of the film, on another red carpet, Les’s murderous musings only fade once he’s acknowledged by his old disciple. As soon as Toby waves him over, Les’s grizzly face crumples into delicate joy. Buscemi’s smile warms the frame. He walks through the faceless crowd into Toby’s good graces. This is Les’s true desire: to get just a little respect, a little intimate recognition between the two men over their shared bond.

Delirious (2006)

Buscemi’s own life is permeated by personal strife, the kind that seems worthy of a motion picture even if it sounds stranger than fiction on paper. He seems to have weathered these storms guided by principled courage. He was a firefighter for four years before he became an actor. In 2001, he was the victim of a stabbing when he tried to break up a bar fight that included actor Vince Vaughn. Later that same year, he returned to his old firefighting troupe to help in the aftermath of 9/11, after which he suffered from PTSD. He’s since cheered on the fire department both in documentaries and politically, even being arrested during a protest in support of the FDNY. His wife, the artist Jo Andres whom he married in 1987, passed away in 2019 at age 64. Last year, he was the victim of a random unprovoked attack in Midtown Manhattan. Currently he resides in Park Slope, certainly a granola-filled land packed with fairy tale endings. But it’s hardly been a picnic for Buscemi. The lightness he brings to his roles instead suggests Chaplin, dredged up on a high wire between traumatic displacements.

Living in Oblivion offers the most quintessential Buscemi role of the three films. He plays director Nick Reve, shooting a low budget film where mishaps abound. The actress forgets her lines. The mic boom is visible in shots. He’s a flailing wunderkind, coasting on pity and charity. Buscemi’s trademark facial tweaks surface as he fails to keep his cast calm during a relatively tame scene. Such a playful attitude towards chaos suits the actor’s own natural capacity for whimsy. Though he’s easily flustered, he’s light on his feet. As a director in Oblivion, he’s often using his face to express the shades of his exasperation. No one gives him a break. No one steps up to help him out. He’s alone behind the camera, huffing and puffing at his cinematographer and assistant director. His shrill whine builds until he’s shouting at his actors. Horrible coffee, not enough daylight, actors who demean one another. He can never get everyone calm at the time enough to get a good take.

The film is divided into three dream sequences where the film-within-the-film vacillates between color or black-and-white. The final section flips our expectations one more time: now they’re actually shooting a dream sequence. The problem is that something (or someone) stops them every few minutes. Someone always needs a break or time to adjust or flubs the line. The film slowly inches closer to completion only to yank us back to first position. This is a job like any other, grubby warts and all. While monotonous and repetitive at times, there’s something charming in the deconstruction of the filmmaking process. I’ve been a driver on sets. The egos displayed throughout Living in Oblivion are hardly inflated. This tweaked-out, down-and-out director displays a ludicrous need for control (and subsequent meltdown) that’s archetypal of so many Buscemi roles. Both Oblivion and Delirious are directed by DiCillo, offering Buscemi two alternative viewpoints on the alchemy of the Hollywood Industrial Complex. In both, he’s struggling to stay afloat, trying to make his way in a climate hostile to newcomers. His tenacity remains. Often, he’s just as tired as the rest of us even as he pushes forward, collecting the courage to try again despite little reward.

Still, Buscemi is not a well of endless goodwill, he’ll certainly throw you off set once you’ve exhausted his patience. Worst comes to worst, there’s always another gig somewhere down the street.

Living in Oblivion (1995)

Share: