Cracked Actor

Cracked Actor: Lee Kang-sheng

On the pleasures and pains of Tsai Ming-liang’s lifelong muse.

Drifting Through Time: Focus on Lee Kang-sheng opens at 7 Ludlow on Saturday, April 19.

Share:

For me, no body is as synonymous with the cinema as that of Lee Kang-sheng. The Taiwanese actor, now 56, is not necessarily the most prolific—he’s starred in roughly two dozen features since his early twenties—but about half of them have been with the Malaysian Taiwanese filmmaker Tsai Ming-liang, who cast Lee in his early TV feature Boys, in 1991, after discovering Lee loitering outside an arcade. Since then, the pair have developed a working relationship that goes beyond that of muse and artist, into a state of symbiosis that muddies the boundaries of life and film. Lee has appeared in every one of Tsai’s aching tales of urban ennui, reprising perennial reincarnations of his alter ego, Xiao Kang, across metropolises including Taipei, Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, and Paris. Tsai has said that it would be impossible for him to make a film without Lee, and to this day he has not done so; their most recent collaboration, Days (2021), takes place partly in the house they share in the mountains around Taipei.

Of course, there are other actors who have grown up on camera. But very few seem to belong almost entirely to it. The closest equivalent might be Jean-Pierre Leaud, the legendary French actor whom François Truffaut first cast as a 14-year-old in The 400 Blows (1959), and who went on to anchor the four-film “Antoine Doinel” cycle, which blended aspects of both the actor and filmmaker’s biographies over the course of two decades. Tsai makes the connection between these kindred souls explicit, going so far as having Xiao Kang watch a VHS of The 400 Blows in What Time Is It There? (2001) and casting Leaud in both that film and the Paris-set Visage (2009). Leaud’s uniqueness, though, lies in his delicate ethereality, as if he were not made of flesh and blood but of celluloid (which makes his corporeality all the more shocking in a film like Albert Serra’s Death of Louis XIV, from 2016, in which a 70-year-old Leaud plays the expiring Sun King); if Leaud is like a Holy Spirit for the cinema, then Lee is more akin to the Son, who in his very incarnation takes on the suffering of the audience.

Boys (1991)

The uncanniness of Lee’s screen presence stems from how, at the same time that he has come to embody an alternate universe, he also derives so fully from a specific time and place. Born in 1968 in Taipei to a father who evacuated from China to Taiwan with the KMT, and a Hokkien-speaking Taiwanese mother, Lee’s family structure was representative of a period when an influx of single male soldiers assimilated into local society and started families; in Tsai’s earliest films, he replicates that family structure through Xiao Kang’s surrogate father (Miao Tien) and mother (Lu Yi-ching). Eleven years Tsai’s junior, Lee belongs to a generation that came of age as martial law was lifted in the 1980s, and state repression gave way to the newfound novelties and dissatisfactions of a liberalizing society.

He describes his early years as common ones for a Taiwanese teenager, taking place mostly in cram schools and the neon-lit nightlife district of Ximending, an experience much like that of the fictionalized version of himself in Tsai’s first proper feature, Rebels of the Neon God (1992). Like most sons, Lee’s standard expression is a combination of supplication and insouciance, all wrapped up in the guise of impassivity. Even as he’s aged from the strikingly androgynous and sexually ambiguous, willowy youth of films like Vive L’Amour (1994) and The River (1997) into a stockier but still boyish middle-aged man, and as Tsai’s films have ventured further into the surreal, Lee has never lost his everyman countenance. (In 2015’s Afternoon, an interview with Lee that Tsai shot in their shared home, Tsai tells Lee that some people on the internet thought he looked like a “potato farmer.”)

Lee is the greatest actor in the world at simply being a body. He’s the greatest performer of eating, sleeping, and walking, because he eats without hunger, sleeps without dreams, and walks without destination. It’s probably for those reasons that Tsai has, throughout his oeuvre, cast him as a man playing a corpse floating on a river, a man paralyzed in a coma, a walking billboard, and a passionless porn star. Lee is riveting when he is peeing into plastic bags, peeing into corners, eating watermelon, fornicating with watermelon, passionately kissing a cabbage, eating that same cabbage, masturbating underneath a bed, being masturbated in a sauna, or simply walking, as he has done for more than a decade now, in Tsai’s Walker series, a modern update of the legend of the Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who famously travelled on foot to India and back to retrieve the holy scriptures. Adorned in a scarlet robe, Lee patiently proceeds, step by painstaking step, through cities like Marseille and Washington, DC, his pace unhurried by the current of people around him.

The River (1997)

In recent years, as Tsai’s output has slowed (he claimed, at one point, that Days would be his last film), Lee has increasingly begun working with other directors, which presents an opportunity to consider how Lee might be distinct from the Xiao Kang character that he has inhabited for the past 30 years. An emergent identity of his own can already be found in the two features that Lee directed—and Tsai produced—The Missing (2003) and Help Me, Eros (2007). In the first, a grandfather with dementia and a boy who disappears at a playground come together; the work was originally meant to be paired with Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), Tsai’s film set during the final screening of a cinema before its closure, in an omnibus work, their two titles in Chinese (Bu Jian and Bu San, or “Don’t See” and “Don’t Scatter”) together forming a common proverb that essentially means “I won’t leave until I see you again.” Lee’s film is the far more worldly of the two; whereas Goodbye, Dragon Inn is haunted both by spectral beings and spectral desires, The Missing focuses on the possibility of reunion, which makes one wonder if the sense of loss subsuming Goodbye, Dragon Inn might have changed had the two parts actually formed one whole.

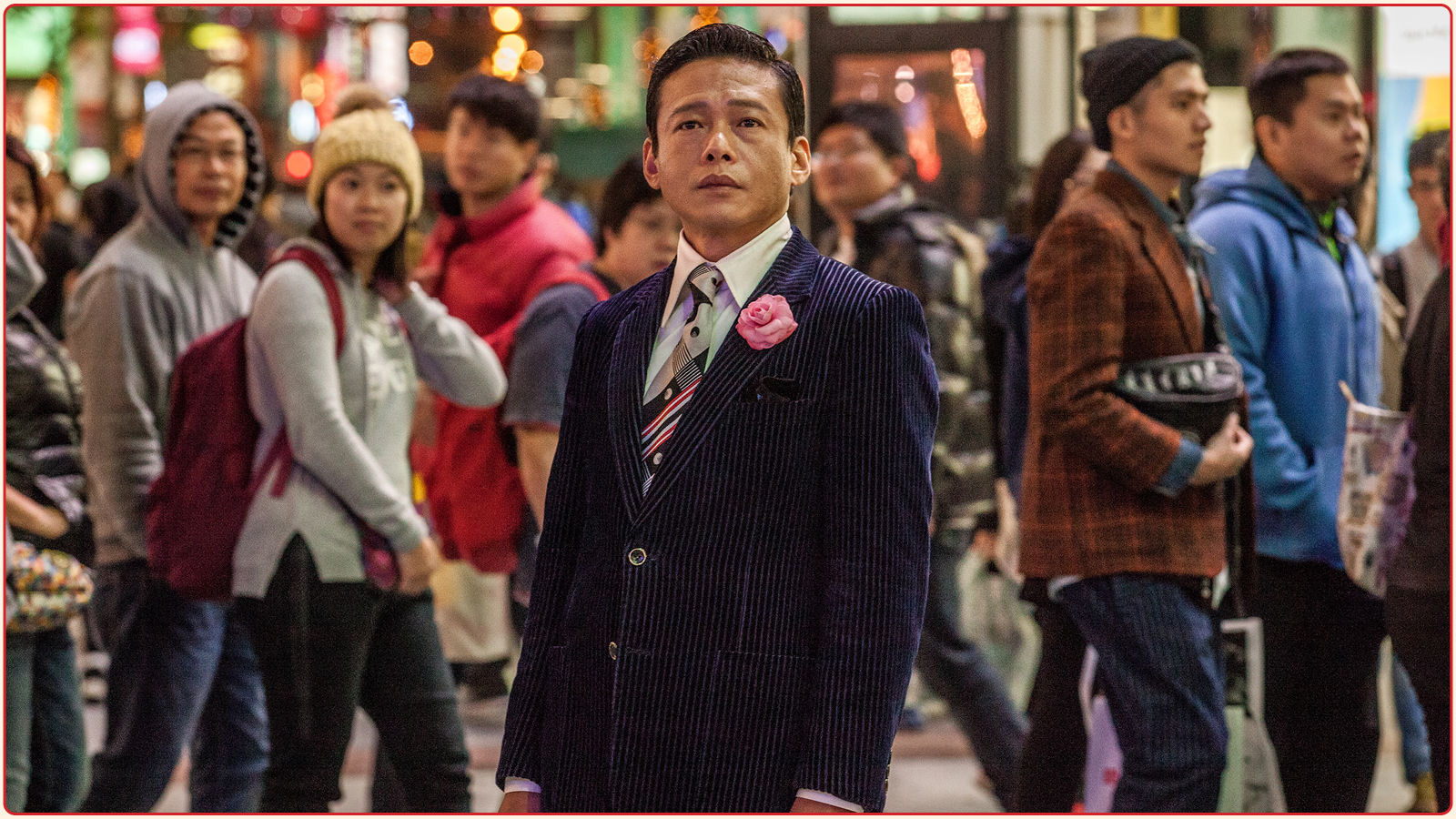

Help Me, Eros, which Lee also stars in, is essentially an erotic stoner film, featuring a pot dealer who grows cannabis in a closet in his condemned apartment, as he becomes involved with a betel nut girl, one of the scantily clad women who roll and sell the stimulant along the streets of Taiwan. When Lee directs himself, the result is much more carnal; the film includes a sequence of increasingly creative sexual positions, and though there’s still the same yearning and tinge of alienation and squalor as in Tsai’s oeuvre, there’s also much more appetite. In describing his idea for Single Belief—a commercial he made in 2016 for Glenlivet, which presents Lee in a series of natty outfits alongside various backdrops in Ximending—Lee complained that Tsai never creates roles for him where he can drive sports cars or wear fancy clothing, so he had to make one for himself. “In Tsai Ming-liang’s world, I’m like the ruins,” he says in Afternoon. “I’ve never driven a Ferrari or led the life of a rich man. So I want to go out and see what possibilities there are.” As roommates, Lee has busied himself with raising Tibetan mastiffs, growing crops, and scuba-diving, while Tsai stays home and paints.

Single Belief (2016)

Which is all to say that Lee’s constraint, his incredible ability to endure any scene for as long as possible and distill it into bare existence, is as much a consequence of artistry as naturalism. His characters don’t suffer from a lack of desire, but from the exercise of continuous restraint, both from within and without. It’s refreshing, then, to see him branch out and collaborate, in earnest, with other filmmakers, even though many of them might be tempted to employ him more as a talisman of arthouse history than to draw out newfound emotions from him. Much is made of his uniquely voyeuristic sensibilities in a film like the Singaporean thriller Stranger Eyes, from Yeo Siew Hua, or his feats of taciturn endurance, as does Tetsuichirô Tsuta’s Black Ox (both 2024), a collection of black-and-white vignettes based on a series of Japanese scroll paintings.

If other actors eventually find the need to play against type, Lee finds himself instead playing against body. For loyal viewers, this can lead to the productive dissonance of seeing him in a conventional, commercial film, like the Taiwanese gangster drama Lost in the Forest (2022), where Lee’s passivity is translated by director Johnny Chiang into a combination of fealty and grievance, or in the forthcoming Fu Xi, from the painter-filmmaker Qiu Jiongjiong, in which Lee plays a prehistoric grandmother who lops off her own tail and cooks it for her brood, before dying. In the New York-set Blue Sun Palace (2024), from Constance Tsang, he plays a man on the run from his debts who becomes intertwined first with one massage parlor employee, then with her colleague; there’s tragedy in the film, but in the beginning, at least, Lee is about as happy-go-lucky as he’s ever appeared, with more lines in the first scene than he has in some of Tsai’s entire films.

The pathos of Lee’s performances lies in the continuous presence of pain, even under pleasure. That stems, in part, from Lee’s own biography; he has suffered from often debilitating neck pain ever since The River (which centers on Xiao Kang dealing with the same condition), and it was featured again in Days, which foregrounds his search for a remedy. But it also reflects the Buddhist tenet that pain is the basis of life, from which pleasures can only offer temporary relief; at the same time, we should never cease striving to alleviate the suffering of ourselves and others. We’re fortunate, then, that Lee has been willing to bear that suffering over at least one lifetime on camera. Although, when Tsai asks him in Afternoon whether he’d like to work together again in the next life, Lee responds, “I’ll be the director, and you’ll be the actor.”

Blue Sun Palace (2024)

Share: