Essay

Bye Bye Love

On Fujisawa Isao’s recently rediscovered gender-bending crime caper.

Share:

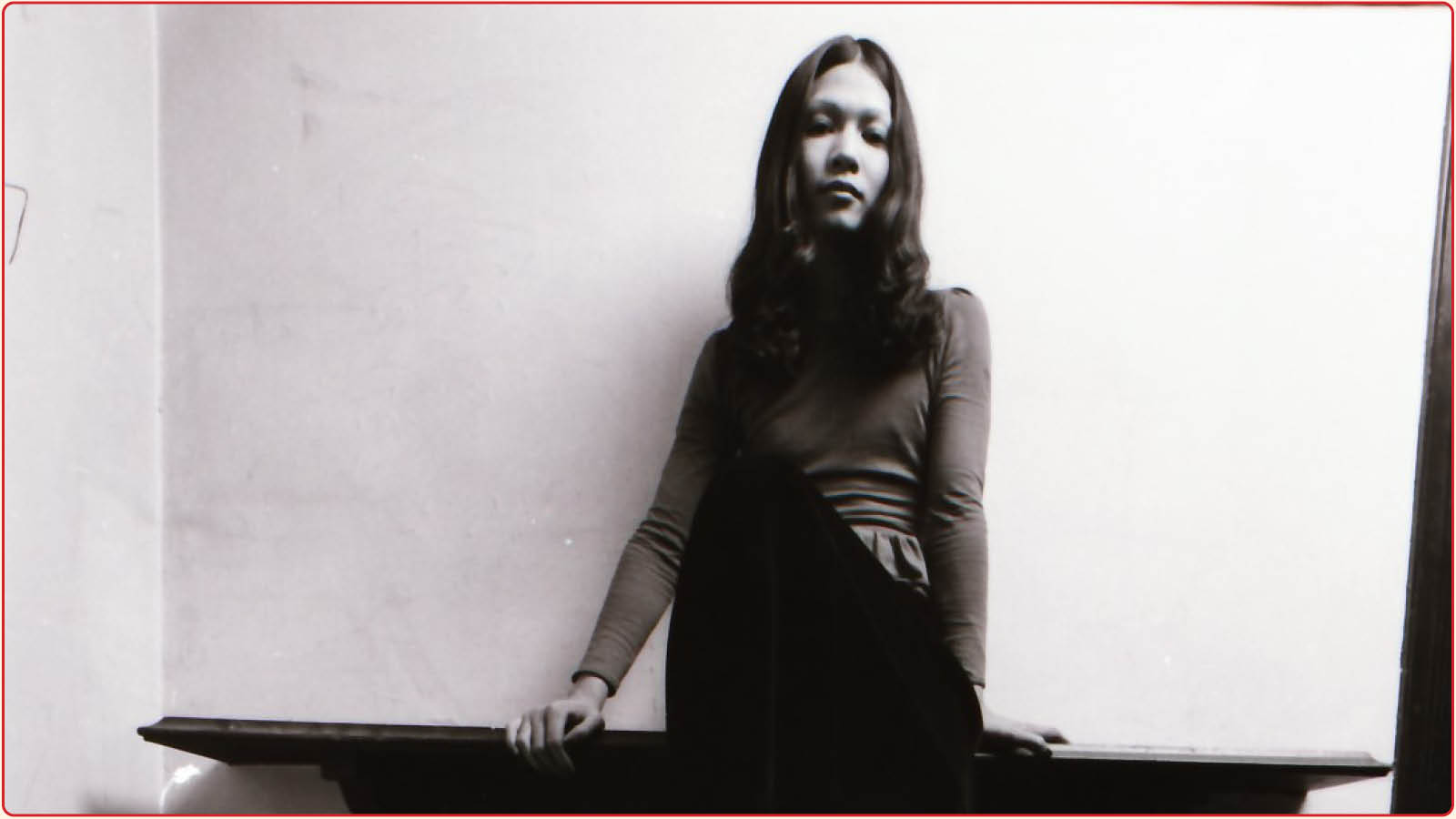

All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun, sure. But what makes a girl, exactly? Long considered lost until its 2018 rediscovery in a film lab warehouse, Fujisawa Isao’s 1974 road movie Bye Bye Love—an avant garde ballad of lovers-on-the-lam in coastal Japan—takes the formula widely attributed to Godard and flips it inside out, leaving us to question the idea of gender, identity, even nature itself. “I’m not a man or a woman. I’m nobody,” says Giko (Miyabi Ichijô), the gender-fluid enigma at the film’s center. “We’re like forms of matter.” Adrift between states of being, theirs is a world of malleable performance, in which the self is a slippery vessel.

A subversive slice of queer cinema whose rhythms embody this mutability, Bye Bye Love was the first and only feature directed by then 31-year-old Fujisawa, a filmmaker who had worked as an assistant director on Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes (1964) and The Face of Another (1966), and on a handful of yakuza movies for genre journeyman Yasuo Furuhata at Toei Company. Under the spell of the French New Wave and influenced by a rapidly changing youth counterculture, Fujiasawa left Toei in 1972 to write and direct his debut feature, working with minimal resources, shooting on 16mm film, and employing a cast of largely non-professional performers. Playful, anarchic and unusually prescient, Bye Bye Love feels like a transmission from a gender-queer future that had yet to be defined.

True to the Everly Brothers classic with which it shares a title, the film begins with heartbreak. “Fucking bitch!” spits deadbeat twentysomething Utamaro (Ren Tamura), brooding next to a poster of a wide-eyed blonde in downtown Shinjuku. He’s just been dumped by his girlfriend when he collides with Giko, who’s making a fast getaway from a bumbling street cop. Asked to foil the pursuit, Utamaro trips the officer, swipes his gun, and catches up with Giko: a vision in tinted shades and flowing dark hair, like some uncanny mix of Kaji Meiko and Jim Morrison (indeed, they’re carrying a record by The Doors). Together they abscond to the apartment of Giko’s American embassy boyfriend (hilariously named Nixon), where they fall into bed and Utamaro discovers—to his initial frustration—that Giko is nonbinary and female-presenting. Moments later, Nixon returns and threatens them at gunpoint. “Go home, America! This is Japan!” barks Utamaro, before shooting the expat dead. Now wanted killers, he and Giko hit the road in the deceased’s Buick convertible, tearing off in the direction of Aomori.

Bye Bye Love (1974)

Though not without a hint of the homoerotic, the American outlaw road movie was, at that point, a largely heterosexual affair, with a brash, propulsive energy that flourished in New Hollywood hits Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Easy Rider (1969), and in the bleak, open-highway existentialism of Vanishing Point (1971) and Two-Lane Blacktop (1971). While Bye Bye Love shares the genre’s general narrative framework (its closest cousin is 1973’s Badlands), it takes the transformative promise of the road movie—its flight from straight society; its playground for personal and political change—and bends it toward an explicit exploration of sexuality, gender and identity.

Like the protean couple at its heart, Bye Bye Love is a film in a strange state of flux, alternating between bursts of kinetic action and experimental passages that drift toward the surreal. Even its most action-heavy scenes are subverted by the looped pipe-organ soundtrack of Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565,” which sounds on the verge of collapse. Despite its clear stylistic debt to Godard—the splashes of vivid color invoking Pierrot Le Fou (1965), exploding cars, and anti-American provocation—the film is nothing if not a formal synthesis of Fujisawa’s cinematic experience: fusing the psychedelic ambience of Teshigahara with the genre elements of yakuza eiga (Utamaro’s gestural nihilism feels as much a tribute to the tough-guy stoicism of Ken Takakura as it is to Belmondo).

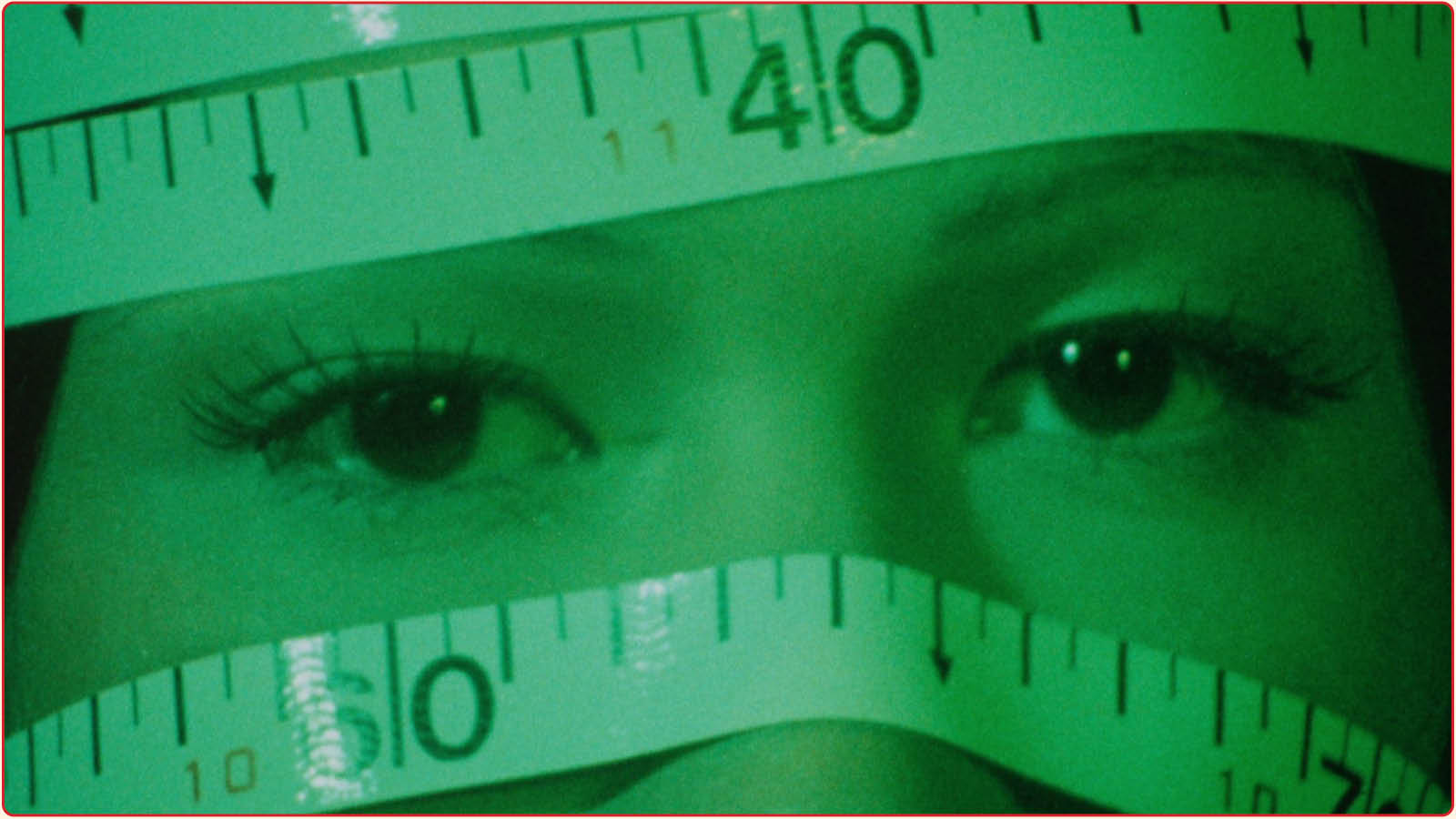

These ostensibly dissonant styles reflect the film’s obsession with exploring identity and the many ways that it can be constructed. Fujisawa captures Ichijô through split lenses, shattered mirrors, and dreamy montages splashed with light spill. He revealingly sets Giko against images of stereotypical Western femininity—department store mannequins with enormous eyes; an oil painting of a buxom beauty with scarlet lips—that are as much a performance of the feminine as Giko’’s own. In an especially striking sequence that recalls Fly (1970), Yoko Ono’s macro-portrait of a woman, Fujisawa deconstructs the image of a cisgender woman that Utamaro has picked up at a motel, unmooring sections of her body—hips, ribs, breasts, tongue—until they become abstract, less than the sum of their parts.

Bye Bye Love (1974)

While gender play had long been a feature of kabuki theater, where men would adopt feminine roles on stage (Bye Bye Love was originally entitled Kabuki Boys), Japanese cinema was, as critic Tony Rayns has noted,“ slow to register the country’s extensive queer subculture.” (The exceptions, such as Matsumoto Toshio’s groundbreaking 1969 drag queen fantasia Funeral Parade of Roses, only served to highlight this.) What’s notable about Fujisawa’s lone directorial feature isn’t just that it’s a contemporary outlier, or one that anticipates the transgressive New Queer Cinema road movies of Gregg Araki and Gus Van Sant decades later, but that it features a progressive, empathic perspective on non-binary life. Writer Ren Scateni proposes that Fujisawa’s film also captures “both ends of the trans experience: the reassuring euphoria when gender identity and presentation align and the thorny, insidious envy of cisgender people.”

In fact, the film not only pushes beyond traditional binaries of male and female, but blurs the distinctions between the “natural” world and the fabricated, challenging the limitations of the body itself. “So, you’re artificial,” Utamaro says to Giko as they make their getaway. “This whole city is artificial,” Giko replies. At one point, Giko nestles among the alien-like tetrapods scattered along the shoreline as though they’re found family; in another, they liken themselves to the aluminum alloy of an airplane’s nose-cone, and suggest “there’s no difference between me and a high heel.” Fujisawa layers distorted electronic sounds to images of a woman, which a voiceover describes as “a strange and mysterious mechanism.” The motif is perhaps most explicit in a standout sequence at a beachside hotel, in which Utamaro and Giko hire a sex worker (played by pinku eiga actress Satomi Oki) and tumble into an erotically—and electrically—charged menage-a-trois, attaching themselves to cables from a transistor radio in a scene that’s almost cyberpunk in its depiction of post-human desire.

The episode prefigures the film’s ghostly finale: an ambiguous kiss-off to preconceived notions of gender that resists easy interpretation. The fatalistic, bullet-riddled myth of Bonnie and Clyde that haunts the movie (an ending that Fujisawa is said to have deemed “a happy death”) means Utamaro is ready to perform the masculine, existential ending for which he’s been practicing. But for Giko, there’s no template on which to base their destination, no gender affirmation at the end of the line. Survival means a temporary return to the underground, the shadows, the possibilities of an unknown future. “If I were matter,” Giko says, “I’d be a journey toward absolute zero.” Hello, emptiness—the Everly Brothers would be proud.

Bye Bye Love (1974)

Share: