Bitter Victory: On OJ: Made in America

BITTER VICTORY:

ON OJ: MADE IN AMERICA

By Nick Pinkerton

From Metrograph Vol. 5, Fall 2016.

Where were you when the O.J. Simpson verdict was read? A rumination on Ezra Edelman‘s film explores this question and what the verdict meant to a high-school student in Ohio.

As best I remember, they herded the student body of my high school out into the lobby, where a classroom television on one of those wheeled dollies had been set up, so that we could hear it being read live. It was 10 in the morning in Los Angeles, one o’clock p.m. in Ohio, and on Tuesday, October 3, 1995, I would’ve been a freshman. I don’t recollect a similar break in the curriculum for the Oklahoma City bombing or the Waco siege flame-out or anything like that, but of course they didn’t enjoy the same lead-up fanfare before the big reveal. Thinking back, it’s a little strange that the honor was extended to the conclusion of the double murder trial of a star running back who neither I nor any of my classmates were old enough to remember as a player, though some of us knew him as Nordberg in the Naked Gun trilogy, the last film of which had been released only three months before the violent deaths of Nicole Brown-Simpson and Ron Goldman. It was strange, too, that when the “Not guilty” was read, my Black classmates, in the main, seemed to take this as a moment of vindication, and that my white classmates, in the main, seemed to take it as a slap in the face. I wonder what the foreign exchange kids were thinking.

Why did a few hundred teenagers in Cincinnati, far from USC or Brentwood or even Buffalo, feel this amount of investment (or any amount of investment, for that matter) in the O.J. Simpson murder trial? Why did people all over the country feel the same psychic involvement? And how did we think we knew which side represented justice? Ezra Edelman’s documentary epic O.J. Simpson: Made in America doesn’t have the temerity to pretend it can fully answer those questions, but it does compile and artfully collate a huge dossier of the essential audiovisual documents pertaining to the Brown-Simpson/Goldman murder case—on the central players and, just as importantly, on their field of play: the city, state, and nation where we lay our scene. It’s a 20th-century American tragedy that moves from the Potrero Hill projects in San Francisco to the Lovelock Correctional Center in Pershing County, Nevada, where Simpson is currently serving a sentence of 33 years for his involvement in a strong-arm robbery of sports memorabilia at Las Vegas’s Palace Station hotel and casino. (This isn’t a case of throwing the book at a perp, but giving him the whole goddamn Encyclopedia Britannica.)

The “real O.J.” is as difficult to pin down as he had been to tackle.

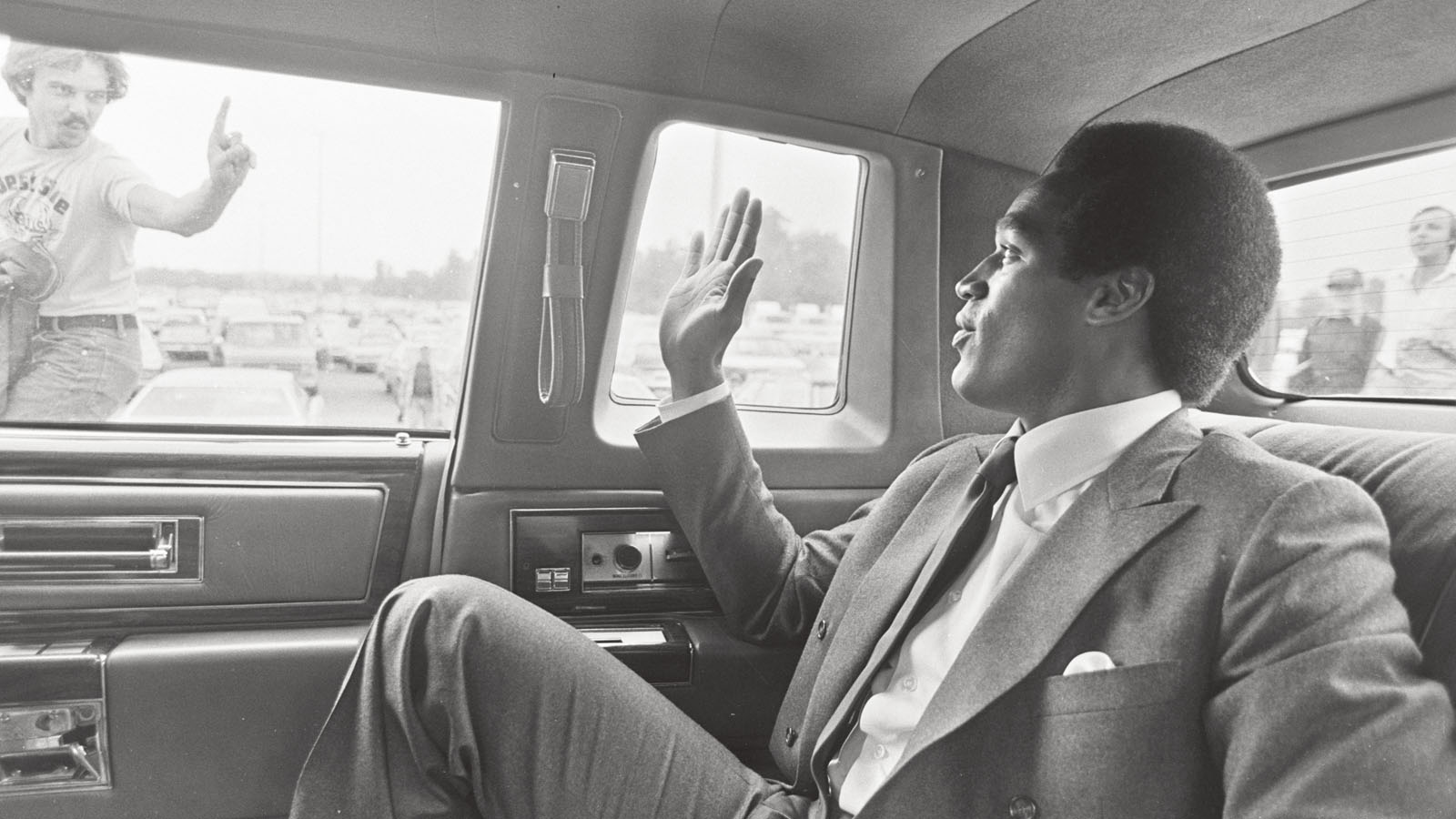

Things had been sad and sordid for a long time at the end of Simpson’s life on the outside, as the footage Edelman and his researchers have unearthed in the fifth and final episode of Made in America makes clear: O.J. wearing an African headdress trying to ingratiate himself with a black church group, O.J. making a heel turn and living louche in Miami, recording rap videos and prank show pilots that no one would touch with a ten-foot pole. If O.J. couldn’t be famous he was going to be infamous, but nobody wanted to see a middle-aged, tarnished Heisman hero in some depressing Punk’d knock-off. Like the man said during the white Bronco chase: “Please think of the real O.J. and not this lost person.”

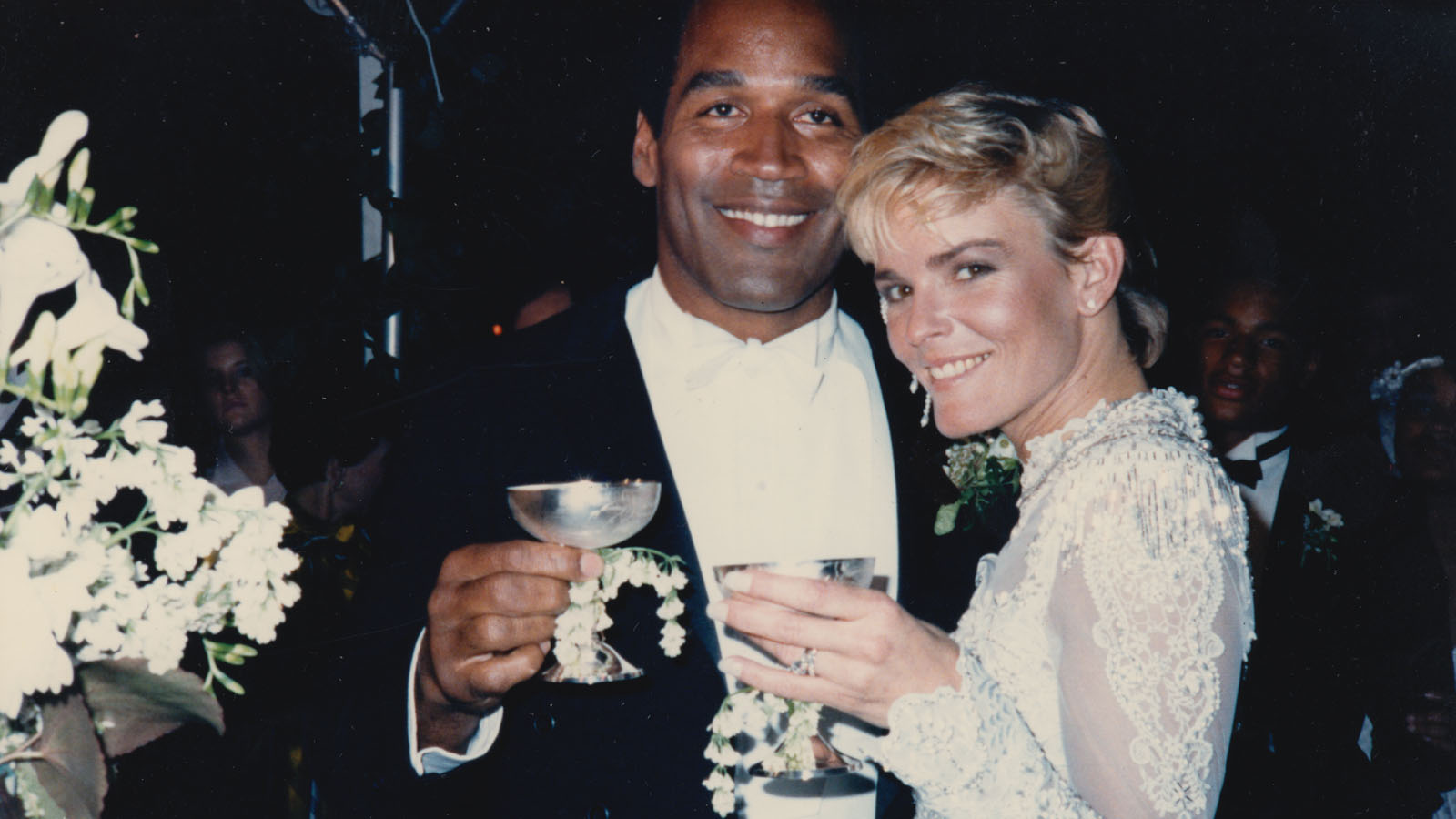

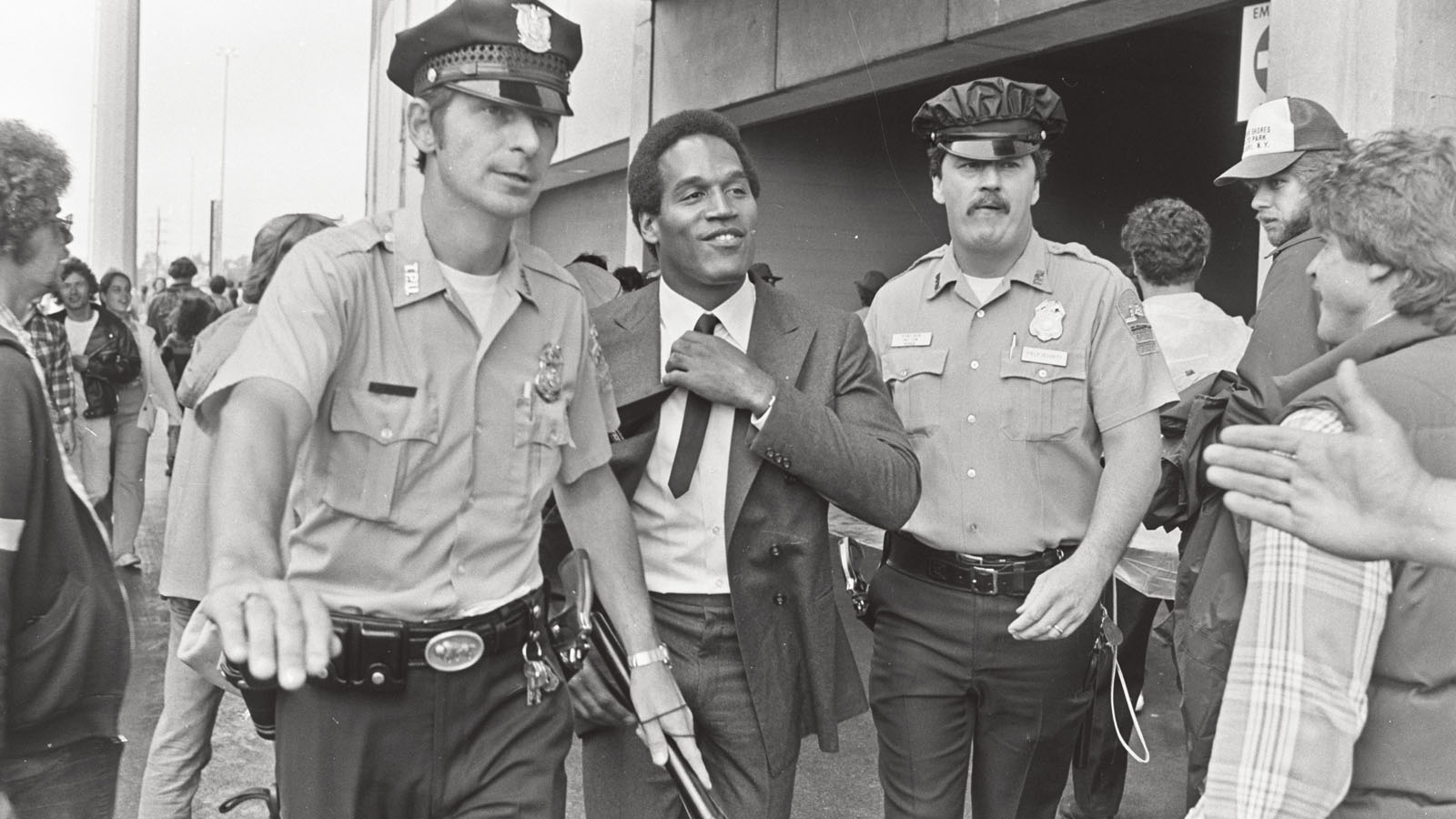

The “real O.J.” is as difficult to pin down as he had been to tackle. There is the O.J. that the sports-viewing public knew, who ran for that game winning touchdown in the 1967 USC vs. UCLA game, the all-around competitor seen in archival footage picking up a 5-10 split on the bowling alley (!), who gave birth to O.J. the pitchman and O.J. the wannabe movie star. There was the private O.J. who grew up poor and black, but relished the company of the rich and white just as soon as his fame won him access past the Brentwood gates. And then there was the guy who the police knew, the guy whose wife would call in the cops on him from time to time when he beat her black and blue, but there was no need for any of it to end up in the papers of course, because it was O.J.

In the process of telling O.J. Simpson’s story, O.J.: Made in America wends through the principal polarities that make up our national life: public and private, black and white, male and female, rich and poor. Through archival footage and incisive, indefatigable interviews, Edelman maps out a constellation of characters every bit as compelling as his film’s ostensible subject: obliviously racist old businessmen, a post-op transsexual helicopter pilot who filmed the chase, and the haunted, disgraced Mark Fuhrman, the only figure whose howling hunger for approval might equal O.J.’s own. There are also the absent presences of Ronald Goldman and Nicole Brown-Simpson, found here in tearful eulogies, frantic 911 calls, and as grisly remains viewed in artless crime scene photographs, a hard core of physical fact that disappeared in the ensuing razzle-dazzle. And finally there is the LAPD, also on trial, and the City of Los Angeles.

It’s not the whole story, but it’s as much pertinent information as you can fit into seven-and-a-half hours of screen time, and it’s a hell of a lot more than any of us knew back in 1995 when we’d heard the verdict read and cheered or mourned teams that we’d all been assigned to without anyone asking our permission. “The resentment that African-Americans had towards whites was shocking,” says Peter Hyams, who’d directed O.J. in the 1978 Capricorn One, of the ensuing celebrations and the cries of “Payback for Rodney King”—this just six years before my hometown had its own riots, spurred by the police shooting of an unarmed 19-year-old named Timothy Thomas. Because O.J.: Made in America appeared between the emergence of #BlackLivesMatter and Colin Kaepernick taking a knee, there’s a temptation to call it “timely,” but Edelman never sacrifices the specifics of his story for trite historical syllogisms. As much as it is about a continuum of race relations, it’s about the exact details of a recent, distant past when, per one of the acquitting jurors, “We took care of our own.” The past, as the saying goes, is another country—and here it’s our country. •