Essay

Alice Diop’s Looking Glass Subjects

On subversive intimacy in the debut feature from the French Senegalese filmmaker.

Share:

The cinema of French filmmaker Alice Diop is one of simplicity, a description often mistaken as a synonym for “understated.” To characterize Diop’s work as the latter recalls the kind of fawning language one expects to bend the ear of of the Academy. Diop’s cinema—for example, the documentary On Call (2016) and the recent narrative feature Saint Omer (2022)—turns its focus on the bureaucratic and racist structures within and around Paris and has little, if any concern for institutional approval or niceties, instead focusing on the small tyrannies of everyday life that are typically elided. What distinguishes Diop from her peers is a refusal to let intimacy stand in the way of political or social critique. Her films examine objective injustices with an unabashedly subjective interest.

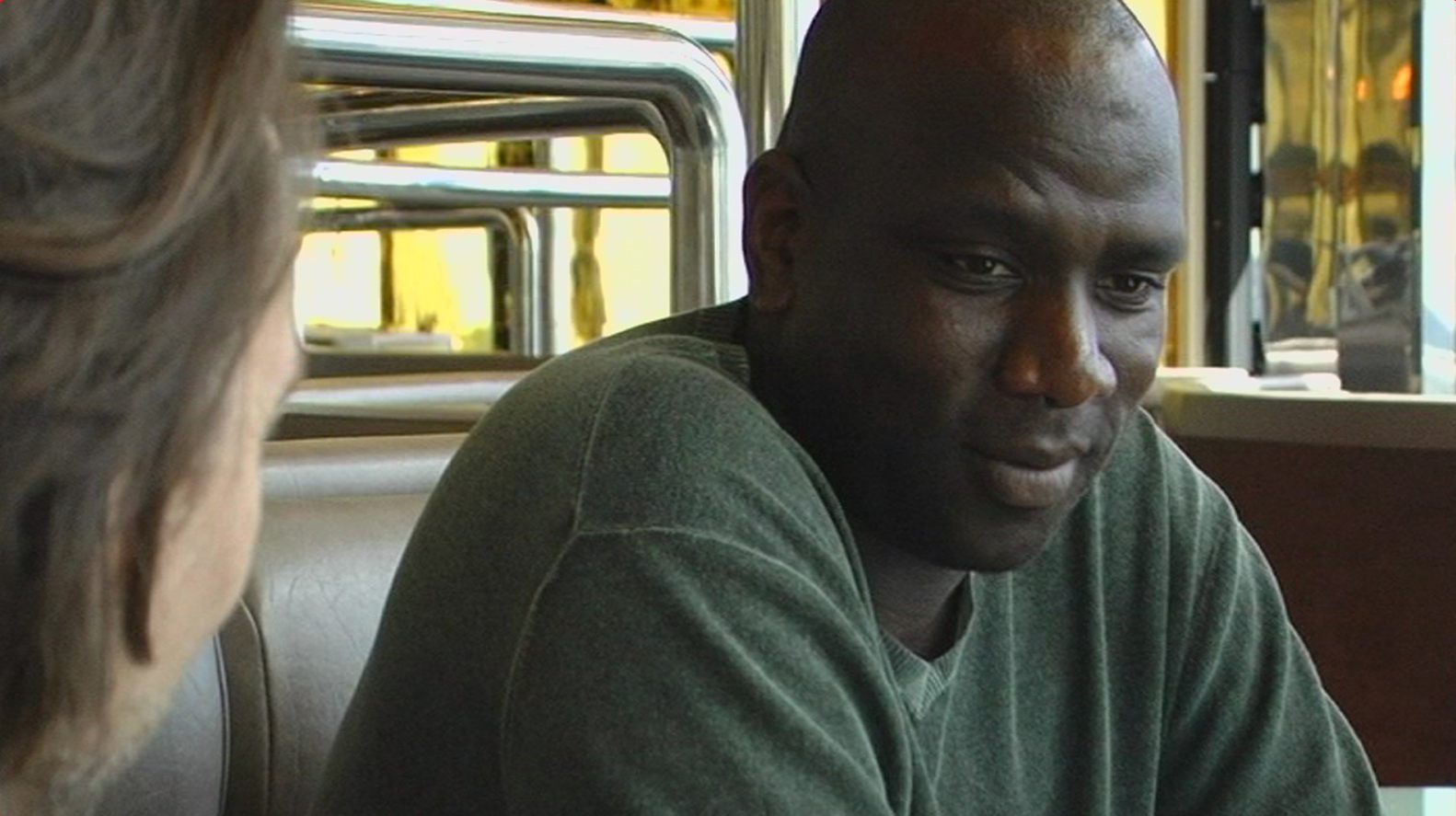

It’s exactly this entangling of filmmaker and subject that comes to the fore in Diop’s first documentary feature, 2011’s Danton’s Death, which won the Library Award at the Cinéma du Réel Festival and the Etoile de la Scam Award in 2012. The film follows the efforts of an aspiring Black French actor named Steve from the housing projects of the greater Paris region of Department 93. Throughout Danton’s Death, we watch as Steve—a tall, dark-skinned man in his mid-twenties with watchful eyes and a pensive, sometimes skittish demeanor—is given rough motivation by his acting teacher at the Cours Simon theater school in Paris. Steve is told to be louder, more imposing, more present in his acting. During a private review with his teacher about Steve’s progress after three years at the school, his teacher commends him for his hard work and zeal, but chides him for his meekness, his inability to project. “It’s important to avoid systematically staying on the sidelines,” his teacher says.

Danton’s Death (2011)

In Danton’s Death, compliments mask veiled insults and praise comes bundled with withering criticism. The audience is not privy to any other actor’s treatment at the Cours Simon because it’s clear that a comparison would be pointless. Steve is seemingly the only Black participant there, “a kind of a walking caricature of all the clichés that people can have about the ‘youth of housing projects,’” as Diop said in a 2011 interview with Africultures. Revelatory in her documentary work, including 2020’s We, about the clashing of lives on the Parisian rail line, is the depiction of mundane violences, many of them products of unthinking contradiction and racial bias. In Steve’s case, it may be all well and good for his teacher, classmates, and the head of the school to push their fellow student to assert himself, to embrace his stature and use it to his advantage on the stage. But, predictably, Steve is only ever given “Black” roles to work with: the gangster, the pimp, the driver in the school’s onstage rendition of Driving Miss Daisy (1989). When he voices his frustration to Diop in interviews throughout the film, Steve laments his interlocutors’ own ignorance and their constant, repetitive emphasis on simply doing the work. For Steve, the conversation is not one of ability or motivation, but a lack of imagination.

The suffocating politeness Steve experiences behind the scenes reflects the falsity of an alleged equal opportunity open to all students at the Cours Simon, but it also opens out on the wider project of Diop’s work. Steve is both a symbol and a real person, an abstraction illustrating a broader, more universal prejudice and a subject worthy of his own story. In that same 2011 interview, Diop said, “The subject of my film is rather about how to escape from the confinement of the gaze of the Other, how to invent one’s own life and become the person of one’s choice, despite what others project on us, despite the place and role they assign to us.”

Nomad (1982)

Such self-determination is made more difficult because Steve believes his lack of progress in class is not a product of racism or blinkered direction, but a lack of confidence. “Once I have self-confidence, my life will change,” he says to Diop shakily, his eyes red and evasive. For her part, as both documentarian and interviewer, Diop makes no attempt to appear impartial or detached. Her investment in Steve’s self conception and the subject matter at the heart of Danton’s Death is absolute, neither academic nor anthropological. That Diop knows Steve because they grew up in the same project, a detail pointedly not shared in the documentary, is, in Diop’s own words, secondary to her interest in the idealism of Steve’s endeavor. “I claim the right to own any subject,” she has said, no matter the proximity to or distance from her own life.

As for the film’s title, its meaning doesn’t become apparent until the very last scene. Danton’s Death, a late 19th-century play that takes place during the French Revolution, dramatizes the career and execution of revolutionary leader Georges Danton. During the film, Steve mentions his desire to play Danton, thwarted by a director’s rebuke that Danton wasn’t Black and thus couldn’t be played by a Black actor. This rejection echoes throughout Diop’s film, a metatextual double that reaches a fever pitch when Steve, waiting to go on stage as the driver from Driving Miss Daisy, watches another actor playing Danton from the wings. But Diop, as idealistic as her subject, isn’t interested in the kind of po-faced didacticism that would leave this dour image as the final breath of the film. In her own way, at the very end of Danton’s Death, she extends to Steve a quieter, though no less impactful stage upon which to act out the role he never got. “Show my head to the people,” Danton said to his executioner before the guillotine. “It is worth the trouble.”

Danton’s Death (2011)

Share: