BREAKING DOWN BREAKDOWN WITH JONATHAN MOSTOW

Interview

BY

NICK PINKERTON

“You should be kicking their asses!”

Breakdown plays Metrograph Saturday, January 15 at 8:30pm.

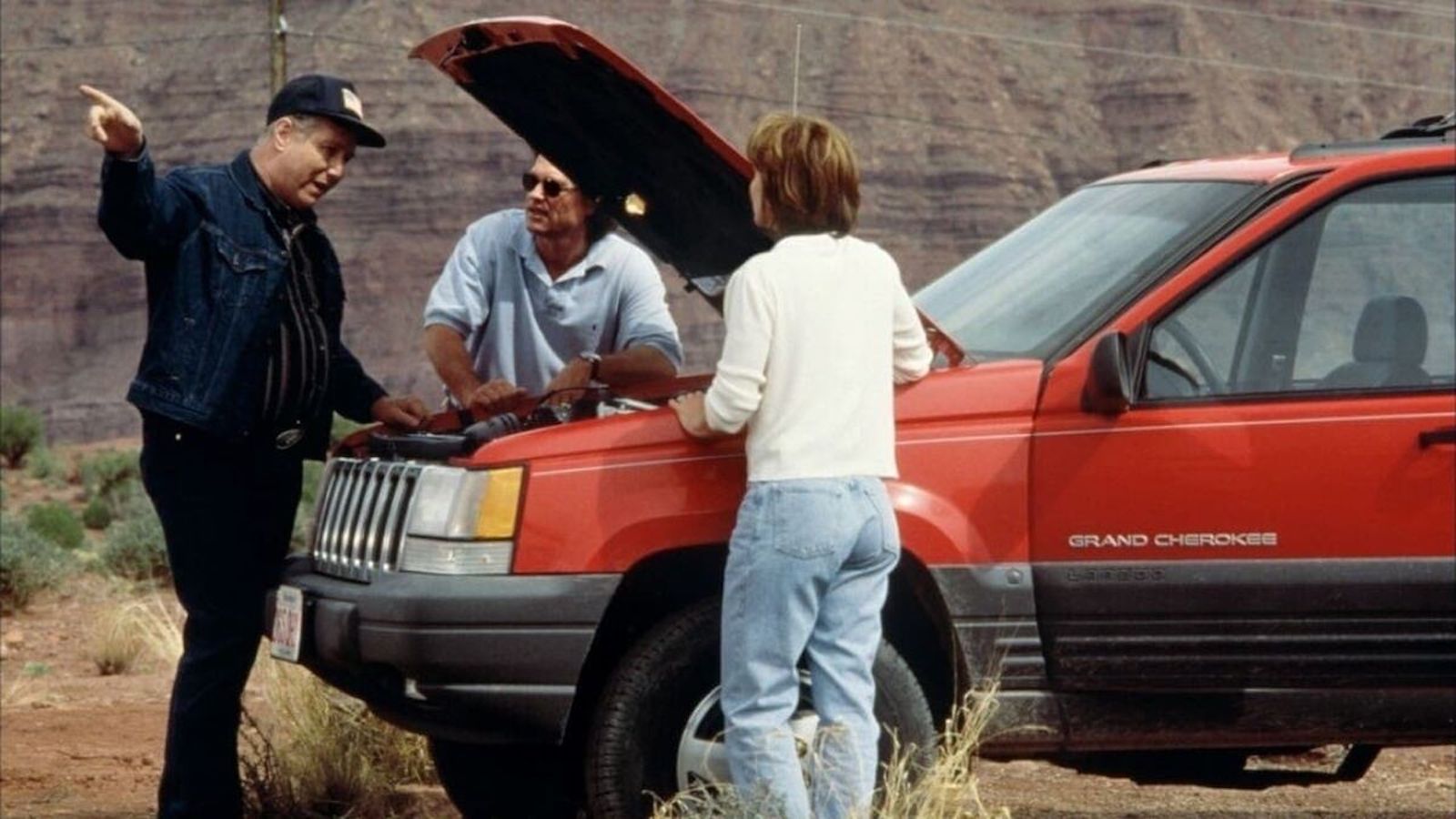

Released in the spring of 1997, when its director was in his mid-thirties, Breakdown was Jonathan Mostow’s first studio release and star vehicle, anchored by an unusually panic-stricken performance by Kurt Russell. Crossing the southwestern desert in a cherry Jeep Grand Cherokee with wife Kathleen Quinlan, en route from Boston to a new life in San Diego, Russell’s khaki-clad everyman runs into car trouble. The couple are relieved when “Good Samaritan” trucker J.T. Walsh shows up to give the missus a ride into town while Russell waits with his precious ride, but when she doesn’t arrive at her destination, our hapless hero has no choice but to undertake a harrowing rescue mission.

In the years following Breakdown, working in submarine pictures (2000’s U-571), sci-fi (2003’s Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines; 2009’s Surrogates), and down ‘n’ dirty DTV action (2017’s The Hunter’s Prayer), Mostow would repeatedly prove himself an admirably pretension-free genre utility player of the sort that the increasingly tentpole-oriented studios don’t much know what to do with these days, though they’re sorely missed by fans of smart, stripped-down filmmaking. On the occasion of Metrograph’s screening of Breakdown, he took time to speak with the Journal about the film’s gestation, the lessons he learned on-set from Russell, and much else besides.

Could you tell me how the film came together. Were you involved with the project from the get-go?

So, it had a weird, weird origin. Several years earlier I made a low budget kind of action thriller [Flight of the Black Angel], and in the course of making it I had run out of money. I happened to play poker with a guy who worked for [independent producer] Dino De Laurentiis, so one night at the poker game, I was like, “Aw man, I got this movie, and we’re out of money, and it’s a shame because I think it’s going to be good.” My friend had seen a three-minute promo I had cut together, so he was like, “Let me hook you up with Dino. Maybe Dino will give you the money to finish it.” A couple of days later, I went into Dino’s building and showed some of the footage in the screening room, and he gave me money to complete the film in exchange for some foreign territories. That began a relationship with Dino.

We developed some movies that never came together. One was an adaptation of a Stephen King short story. Dino had made it into a movie that Stephen King himself directed back in the ’80s, it was called Maximum Overdrive. It’s not getting inducted into the Registry of the Library of Congress anytime soon. Though weirdly, the soundtrack, which was done by AC/DC, sold a gazillion copies… Anyway, we wrote a script and were starting to scout locations, heading toward actually making the film, then Dino’s head of business affairs came in one day and said, “We have a problem. We can’t call this Stephen King’s…” On the poster, it was going to say, “Stephen King’s Trucks“, that was the name of the short story. The whole financial reason to make the movie disappeared because if you can’t put Stephen King’s name big on the poster, the financing dries up. I was like, “Oh crap, I’ve spent a year on this, I’ve developed the script, I’ve scouted locations for this movie with trucks out in the middle of the desert,” and so in a sort of a desperate Hail Mary to save the day I was like, “What could I do? I know these locations, and I’ve got trucks on my brain.” So I spontaneously came up with the idea for Breakdown, wrote the script on spec, brought it to Dino, and Dino was like, “Okay, great. We’ll make this,” and it rolled from there.

The movie has nothing to do with Maximum Overdrive, or the story ‘Trucks.’ It’s one of those weird things where had I not been working on that, Breakdown wouldn’t have happened. My thought was, “I can make this. It’s out in the desert, I barely even need location permits, I don’t need lights, it can be done so cheap.” Then it turned into a bigger movie because we had a big movie star, Kurt Russell, and there were all these bizarre permutations to make it work in the schedule, as Kurt had to be at his house every night in Los Angeles. Every day, we were flying him by private jet to wherever we were shooting out in the Western United States.

At what point did Russell come on board?

I had always been a huge fan of Kurt’s. In fact, I had met Kurt several years earlier when I was going to direct a movie called The Game, which ultimately became a David Fincher movie starring Michael Douglas. But that was a movie I had developed originally. So I met Kurt, and we wound up having like a two-and-a-half hour meeting, we totally hit it off. Ultimately, he passed because at that point I hadn’t really done anything except this low budget film, made for a million bucks. So when it was time to do Breakdown, Dino said, “Who do you want?” and I said, “Well, my dream would be Kurt Russell.” Dino wound up making a crazy deal to get Kurt-and Kurt liked the script, but he was very busy, he was about to start shooting Escape from L.A. and he wanted to take some time off, and Dino was in a hurry. So Kurt was the first guy we went to, and luckily, he said yes.

I always felt Kurt is probably the most underrated movie star of all time… he’s the most cinematic actor that, I think, has ever really worked in Hollywood.

It’s a very interesting and effective piece of casting. You mentioned Escape From L.A. and the Snake Plissken character; often Russell’s doing these gung-ho, serenely confident characters. Whereas here he’s almost used against type as somebody who’s completely over his head from jump, he’s not this extremely physical guy, just an average dude scrambling to improvise his way out of a jam. It’s interesting that you’d been developing The Game previously, because there are some definite parallels there. .

I always felt Kurt is probably the most underrated movie star of all time. I know that’s a giant statement, but… And I say that for several reasons. First of all, there are very few actors who cross genres like he does. There’s a whole universe of people who are Kurt Russell fans based on Captain Ron, Overboard, and probably now the Christmas movies he does on Netflix. For them, he’s just this fun, warm, fuzzy, goofy guy. Then there’s the action fans for whom he’s always going to be Snake Plissken. He’s also done dramas, like Silkwood and then he’s got the Quentin Tarantino crowd… so, he’s just incredibly versatile. But the reason I really say he’s so underrated is that he’s the most cinematic actor that, I think, has ever really worked in Hollywood.

One of my favorite examples of this-two of them, actually-are in Silkwood. You don’t think of him when you think of Silkwood, necessarily. You think of Cher and Meryl Streep and then Kurt was like third billing. But there’s two scenes in that movie that if you are an actor, or studying actors, or directing for that matter, I think they are obligatory viewing. There’s a scene where-and keep in mind I haven’t seen this for 25 years, so, you know, hopefully I’m not mistaken-where the three of them, Meryl, Cher, and Kurt, are flying to Washington D.C. They’re sitting in coach, three across, and all the dialogue in the scene is between Meryl Streep and Cher; one’s in the aisle, and one’s in the window, and Kurt’s got the middle seat. So, he has nothing to do in this scene but sit there-and all you can do is watch his eyes track the conversation. You watch him, and you totally understand what he’s feeling and thinking. Another scene is near the end in that film, after Karen Silkwood has died, and the house has been scrubbed clean of all possible radioactive contamination, so it’s a shell of the house that he’d spent so much time in. He goes back, and he just walks through the empty house. He’s just looking around, and you, the audience, are totally in his head. He has just this incredible ability to communicate thought and emotion just with performance and no dialogue.

One of my favorite moments in Breakdown exemplifies exactly this, when he slips into the bathroom of the bank where he’s withdrawing ransom money and is rifling around, trying to find a plausible weapon-you almost see the gears turning when he tries out the toilet plunger handle, thinks: “No dice.”

Frequently in our discussions preparing for the movie-and we had the luxury of a huge amount of prep time because he was filming Escape From L.A., which was a night shoot, like 70 nights in a row. He said, “Look, I have to stay up. I’m shooting Monday through Friday nights, and then on the weekends, I don’t want to go back to regular schedule because I’ll be a wreck. I’m going to stay on my night schedule on the weekends, so if you’re game, come over each weekend after dinner and I’ll work with you as late as you’re willing to stay up, and we can go through the script.” So, for months, I would go over to the house every weekend, usually one or two nights each weekend; I’d get there, I dunno, eight o’clock and I’d stay until four in the morning. We would sit in the den-it was totally quiet, everybody had gone up to bed-and we would talk through the script. Just beat by beat by beat by beat.

So when we got out there on set, we were 100% in sync . And I can’t tell you how many times in each particular scene he’d say, “Oh, we can get rid of this line of dialogue.” The first couple of times he said that, I was like, “Why?” His answer was always simple: “Because I can act it.” That’s what I learned working with him. We cut a lot of his dialogue because it was better done non-verbally. That’s his true gift in my opinion. He’s a totally intuitive actor. He’s been doing it all his life. I don’t think he’s ever taken a class. He certainly doesn’t need to because he’s just always in the zone.

You know, it’s not a coincidence in my opinion that he’s a pilot. And by the way, Harrison Ford, Tom Cruise, John Travolta-I mean, there’s more guys-but there’s a number of movie stars who are pilots, and it’s not just because they can afford to be. I think it’s the same thing as acting, or a world-class athlete-which, by the way, Kurt was a professional baseball player too. It’s about being in the zone. These stars, they are completely connected to the character. Even the greatest trained actor will tell you that, ultimately, all that technical expertise, when it really comes down to it, they check it at the door, and they try to climb into that zone. Sometimes that training can inhibit you, because it’s hard to release your brain from intellectualizing about the acting process. He is just 100% an instinctual, intuitive actor.

I’m going to say one more thing before I forget, and I apologize for running on. You know, going back to the playing against type. So, yes, absolutely, but this movie wasn’t the first movie to use Kurt in this way. In Unlawful Entry… In that movie, I vaguely recall, he played a sort of normal guy in a kind of over-his-head situation, but I think his part in Breakdown is probably his most Regular Joe guy, a little soft around the middle.

There’s a little bit of that in Executive Decision, too, where Kurt’s supposed to be playing cerebral support to all-American badass Steven Seagal on a rescue mission, then has to step up after Seagal gets murked.

It’s funny, there’s something I only learned recently that relates to this. The film was never on Blu-Ray until this last year-people for years used to say, “Why can’t I find your movie on Blu-Ray?” Finally, to their credit, Paramount came to me about a year-and-a-half ago and said, “We’re going to actually put this out as part of our Paramount Presents series.” They poured a lot of money into it and did a really beautiful re-master. They hired a production company to do a bunch of making-of things, and I’m a bit of a pack rat, so I went into my archives and found all this old, cool stuff, and then Kurt and I did a commentary track. So, I actually got to hear this directly from Kurt just last year, but he said when we were doing Breakdown, his long-time makeup guy was like, “Ahh, this movie’s no good. ” Kurt was like, “What do you mean this movie’s no good?” He’s like, “Come on. You should be kicking their asses!” Kurt thought that was really funny. But the guy wears the Team Kurt jersey, and it just bugged him to watch Kurt be on the losing end of the stick.

There are certain actors that audiences have a hard time accepting getting pushed around. Clint Eastwood’s White Hunter Black Heart (1990) is the only movie where Eastwood gets whipped in a one-on-one fight-in everything else it takes at least a couple goons to subdue him. And even if you don’t know that watching the scene, it’s kind of shocking.

The final anecdote I’ll share is that a few weeks before the end of filming, we were hanging out between shots, waiting for the lighting or whatever, and Kurt says to me, “You know, I’ve been coming home every night from this movie telling Goldie [Hawn], ‘I’m in pain. I’m in physical pain making this film,’ and I don’t understand it because I’ve done action films with far more demanding stunt work than what’s in this film. But I come home, and my shoulders hurt, my neck hurts. I just don’t understand.” Then he said he finally figured it out. He realized it’s the character. He’s playing this character who’s walking around, hunched up all the time. I kind of kept this to myself, but my immediate thought was, “Yeah, because you’re playing me in this thing.”

There are little things, costume-wise, which are very funny in the way they cut him down to size. Not only his initial, tight-assed appearance in the crisp chinos and the tucked-in polo shirt but, as he faces more and more travails, the way the shirt comes untucked, and it looks oversized so he looks like a little kid swimming in his dad’s clothes.

Totally! Yeah, that was all very specific and intentional. Again, what made it such a joy to work with him, the reason it really clicked was that we both share fundamentally the same belief about filmmaking, which is the story is the star and it is all about telling a story, and whenever you can tell story visually, that’s a great thing. So, you see how this guy’s dressed, even the car he’s driving, it’s this yuppie mobile… He doesn’t need a four-wheel Jeep. He’s coming from Boston! Who needs that if you live in the city? And it’s not even a rugged Jeep, it’s cherry red. All these cues give you who the character is, and of course, the most important thing is just behavior; we both believed you reveal character through behavior.

One of the things we did on the Blu-Ray is… Long story why it existed, but there was an alternate opening for the film, which I never thought we needed. It’s the only part of the script I didn’t write. We actually shot it, it was even in our first preview screening. Ultimately, I was able to convince everybody to take it out because the film was better without it, but it came from the typical studio mentality, because it’s all fear-based and everybody’s nervous, that we need to know more about the character. My belief was, you meet this guy and you get who he is. And the fact is that you, the audience, are going to become him, because a lot of it is shot from his point of view. So, we don’t need to know, in any great detail, his backstory. Particularly with an actor like Kurt, who really just emotionally pulls you in.

What was, may I ask, the opening scene? I say this because one of the things I so admire about the movie is that you never have any big reveal. You never fussily fill in any backstory detail, the movie doesn’t open with Kurt at an urban climbing gym to exhibit his latent toughness, we never learn he’s actually got this hidden set of he-man skills, he was a Navy Seal in a former life, or whatever.

My original screenplay started exactly as the movie begins. Just a couple driving on the road. That’s the movie everybody had agreed we were making. And then there was a point, before Kurt got involved, where I thought, “Oh, it’s not really going to happen.” Because every movie I’ve ever been involved with-every movie ever that anybody’s been involved with-always has some point where it bogs down. I’ve never seen a ceremony where anybody who got an award didn’t say, “Yeah, it took 85 years to get this movie to the screen.”

So, I thought it wasn’t happening, and while I was gone someone was talking to Dino and his wife Martha, who was the producer on the film, saying, “You can’t start a movie with a couple driving in the desert. You need backstory. You’ve got to know all this stuff about them.” So Dino commissioned another writer to write the backstory. Suddenly there were 10 pages, and it starts in, I think, Central America, some war zone; Kurt is a video camera man, he normally shoot sports but he’s got this freelance gig on this news crew, and he winds up filming a girl getting shot by a sniper. It traumatizes him, he flies home to Boston, and his wife picks him up at the airport; they talk about how unhappy he is, and he’s going to take this job, they’re going to move to San Diego. There’s like 10 minutes of stuff! The film opens with a tank driving over the camera. I remember filming it going, “This is crazy. You don’t need this.” And I just couldn’t convince anybody.

But I was very loyal to the De Laurentiis’, and they were giving me this big opportunity, so I’m like, “Okay, I’ll film it, and at some point, I’ll convince everybody we don’t need it.” It was only when we were doing our second test screening and I said to everyone, “Will you indulge me in an experiment? Could we book the theater for two nights in a row, the second night let me just pull off the first reel. We’ll start ten minutes in without any of that stuff.” Because everybody was happy with the film, they were like, “Okay, we’ll indulge you,” but they thought it was nutty. Then, to their credit, when the film ended they were like, “We don’t even need to see the cards. That’s clearly the better version.”

One of the things I admire about how the movie opens is how-without doing any of that stuff-it really grounds you, through purely visual language, in what you’re about to get into. Not only that Shining-esque aerial where you see the Jeep going around this switchback turn that gives a sense of the many reverses ahead, but also the almost Saul Bassian opening credits with this webwork of highways crisscrossing, which give the feeling of a lowering net.

It’s funny, I’m smiling that you mentioned Saul Bass because when it came time to do the poster, I pushed really hard with Paramount to do some sort of Saul Bass-type approach. If I had my way, it would have been even more… On a Saul Bass scale, I would’ve been very happy at a 9 or 10, and maybe we got to like a 3 or 4, but that was better than the 0-1 that they started with, which was totally conventional. I’m obviously very influenced by Hitchcock, and certainly was with Breakdown.

Another major element is the score by Basil Poledouris, which is very percussion-heavy.

Prior to doing this film, my only experience working with composers was that we had no money and had to create a scrappy score with little resources. Because this was a studio-sized movie, suddenly I had a big budget for music and could afford a 100-piece orchestra, and a fancy accomplished composer, and Basil wrote a very beautiful score. But… there’s a longer story, if you’re interested in this stuff?

Okay so, basically, I’m a musician myself. I come from a family of musicians so I kind of speak the language. And, not that I had a lot of experience, but the way I had always preferred to work was I want to hear mock-ups of what we’re going to do. I don’t want to show up on a recording stage with 100 musicians and be hearing the thing for the first time. I want to work iteratively; I know what I want sort of musically, I know what I want to feel, and I can hear that in a mock-up. But Basil kept delaying, delaying, and I realized he was struggling, and so I didn’t get to hear the score until I was kind of on the stage. And the music was beautiful, but there wasn’t tension in it.

When we did our test screenings with an audience, I had very carefully crafted this temp score that was full of tension; that’s what we’d been testing the movie with. Then, I remember, we did our final test screening with the finished score from Basil, and I was like, “Ah, jeez, I don’t know what to do. All of the tension is out of the movie.” The president of the studio [Sherry Lansing], to her credit, turned to me at the end of the screening, and said, “Don’t change a frame, but we need a new score.” Of course, they didn’t give me any money for a new score. We had almost no money left in the music budget.

So I had to sit in Basil’s studio and go through each cue, which would be made up of sometimes 10, 50 individual tracks. We’d listen to every single track, trying to piece together something. Then I brought in some other musicians-I wanted a haunting sound, so I found this guy who played an EVI, which is essentially a breath-controlled electronic instrument, sort of like a piccolo. So the opening credits sequence is just one of the percussion tracks from Basil’s original score with the orchestra stripped out and replaced with this single line of this EVI. Then certain cues in the movie, some of the more emotional ones, are exactly as Basil had done them.

It was a horrible experience because it’s no fun for the composer to have his score kind of deconstructed, and the hardcore Basil fans felt I was some philistine who had messed up his beautiful score. In fact, a few years ago, one of the music publishing companies actually put out a three-CD set that’s his original score and then the score we ultimately did, so you can compare the two. All I can tell you is that when we then did one more final screening after I replaced the score, the audience ratings shot way up. That was the movie that was released.

I couldn’t figure out what was happening until one night, around three in the morning, when I was at Basil’s studio in Venice Beach. Back when this was going on, like 25 years ago, Venice had some really dangerous parts. You just don’t go outside at night in some of these areas, there was a lot of gang violence and crime and whatever. And that’s where his studio was! He had underground parking and an iron gate and all that stuff, so we were safe once we were in there, like you didn’t dare venture outside. And on this particular night, at 3 AM, he just said, “I’m going out for a pack of cigarettes. Does anyone need anything?” I thought, “What are you doing? Why would you possibly go out in this neighborhood?” And I realized Basil didn’t have what I have, what most people have, which is a sense of personal safety and self-preservation. I think as a human being he connected with the sadness of Kurt’s character in this scenario, but he wasn’t connecting with the anxiety of it. Some people have certain emotions they literally have a blind spot to. So the score we wound up with, I don’t know that there’s any composer that would have started out to write that score, and I don’t know there’s any composer that could. Basil’s gift for some of that orchestral, beautiful, emotional stuff-he was at the top of his game in those areas, and some of that stuff is really beautiful, and is absolutely there. And so the Bernard Hermann-esque part that I was looking for, I actually wound up going back to a composer I’d worked with before, and did subsequently, a guy named Richard Marvin, he supplied that. I don’t think any single composer could have done that soundtrack in the way it needed to be done.

when Breakdown came out in ’97, that was really the beginning of the big tentpole thing.

At this point I hope you have a sense of how well Breakdown has aged, perhaps because it exemplifies a kind of filmmaking you don’t see coming from Hollywood much now: the mid-budget genre movies that you saw a fair number of in the ’90s, but no longer. It’s the same movie today that it was 25 years ago, but now there’s a collective nostalgia for the kind of movie that it exemplifies: the sound fundamentals, the spatial awareness, the tight, focused plotting… This is pretty thin on the vine today, at least at the multiplex, and these qualities have been your specialty as a director, even in a bigger project like Terminator 3. The loss of these mid-range genre vehicles has been a tragedy for studio filmmaking, but the loss has made what’s so special about Breakdown more evident.

It’s interesting, my influences growing up were the ’70s movies, and also there was a class of made-for-TV movies, the sort of thing that Barry Diller, when he ran ABC, really went in for-these sort of suspense movies for television. I’d watch these movies on the black-and-white TV, because my parents couldn’t afford a color TV, and there would be a couple driving, they would get pulled over by a cop in some Southern town in the middle of nowhere, and all of sudden they’re in this dungeon being tortured, all this kind of crazy, creepy stuff. I don’t even know the names of some of these movies, but when you’re 11 or 12, they make an impression, and they stick with you. So that was an influence coming into Breakdown.

Then, when Breakdown came out in ’97, that was really the beginning of the big tentpole thing. It came out either a week before or a week after… I don’t remember what the movie was called. Volcano?

Oh, yeah. Or maybe Dante’s Peak. One of those CGI magma movies.

Yeah. They’re all interchangeable, to some extent, in my mind. But basically the big spectacles.

By the way, the movie would not have existed if it was in the studio system. It was financed independently. Paramount only got involved when we were halfway through shooting, and the movie would not have happened if the De Laurentiis’ hadn’t risked their own money to start making the film without any studio distribution. Because originally, we tried to set it up at all the studios. All the studios passed, even with Kurt Russell, who was a very meaningful star at that point, because they were like, “Ehh, what is this? It’s just a guy running around the desert.” It’s often hard for studio executives to realize suspense on the page, because usually they’re reading scripts so quickly. For a suspense movie, you have to read it in real time because the suspense is in between the lines. It’s not in the dialogue, necessarily, or the stage directions. And when you have to read 30 scripts in a weekend as an executive, you’re just flipping through to see what happens, and you’ll probably miss it.

But within the beltway of Hollywood, Breakdown was pretty quickly embraced. For a lot of filmmakers and other people who got into the business the same reason I did-because a lot of them had grown up seeing those great movies in the ’70s, not because of giant spectacle movies-it was embraced right from the get-go as a throwback.

In terms of the way the business has changed, where it’s become a tentpole business, these mid-range movies are… When it costs $60M marketing worldwide to open a movie, what’s the point of making a $20 or $30M movie? Just make a $150M movie that has a chance of breaking through.

Added to that is the problem on the financing side, almost every single movie nowadays, certainly in the mid-range and lower, relies on tax rebates, from New Mexico or Georgia or Louisiana or whatever; you’re getting 20, 25, maybe 30% of your budget from this convoluted tax rebate financing. Breakdown was shot in California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona. So, four states. I’m trying to think if I’m leaving anywhere out. Financially, that’s not a model you could even do nowadays.

Which is a shame, because there’s nothing I like better than watching a guy run around in the desert.

I guess if there’s a commonality, all my movies have actually been road pictures. They’ve started at one place-even my submarine movie, U-571, they’re starting in position A and they’re going to position X. There’s a forward narrative momentum that I’m probably drawn to as a moviegoer myself.

When I meet people who’ve done sort of seminal movies, I often ask them, “Could you get that movie made today?” Almost always the answer is, “No, I don’t think so.” Films like Breakdown, and so many others, they just don’t get made. •

Nick Pinkerton is a Cincinnati-born, Brooklyn-based writer focused on moving image-based art; his writing has appeared in Film Comment, Sight & Sound, Artforum, Frieze, Reverse Shot, The Guardian, 4 Columns, The Baffler, Rhizome, Harper’s, and the Village Voice. He is the editor of Bombast magazine, editor-at-large of Metrograph Journal, and maintains a Substack, Employee Picks. Publications include monographs on Mondo movies (True/False) and the films of Ruth Beckermann (Austrian Film Museum), a book on Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Decadent Editions), and a forthcoming critical biography of Jean Eustache (The Film Desk).