Whit Stillman

Interview

Whit Stillman

Interview

BY

Rebecca Panovka

An interview with writer-director Whit Stillman.

Whit Stillman joins Metrograph for a special In Person event, presenting Metropolitan and Barcelona, on Saturday, September 17.

“People who interview [Whit] Stillman often note that the experience is like being in one of his movies,” Alexandra Schwartz wrote in a 2016 article for The New Yorker.

Stillman’s characters are verbose, well-read, highly analytical. They like to talk about ideas, dissecting the ideology undergirding a particular social custom or popular movie. Take the discussion, in The Last Days of Disco (1998), about the Disney classic Lady and the Tramp (1955). One member of the group attempts to convince the others the film is propaganda:

“What’s the function of a film of this kind? Essentially it’s a primer on love and marriage directed at very young people, imprinting on their little psyches the idea that smooth-talking delinquents recently escaped from the local pound are a good match for nice girls from sheltered homes. When in ten years the icky human version of Tramp shows up around the house, their hormones will be racing and no one will understand why. Films like this program women to adore jerks.”

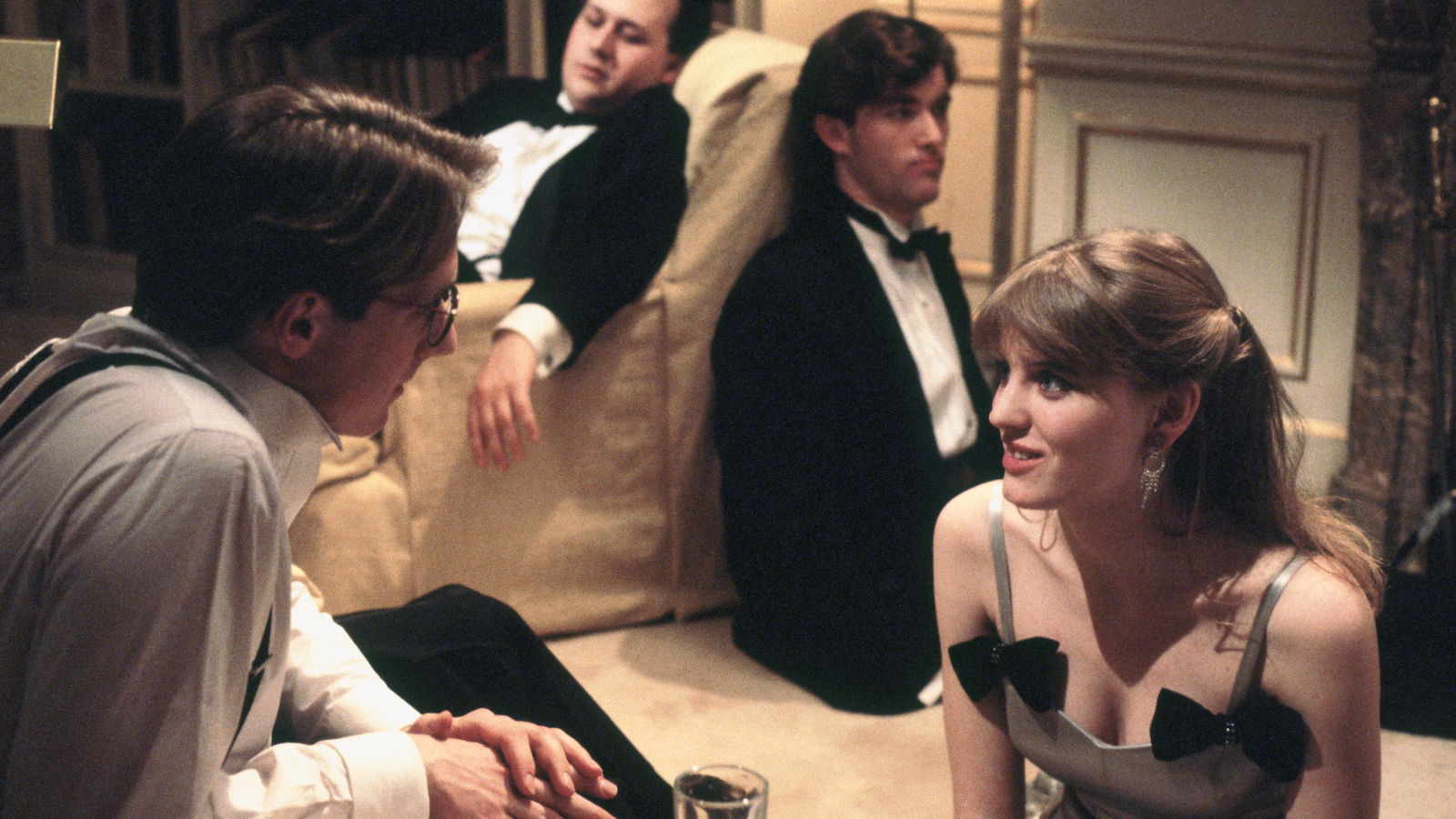

Stillman’s movies, in some sense, are also primers on love and marriage, directed at somewhat less young people. Metropolitan (1990), Barcelona (1994), and The Last Days of Disco—his first three films, which he has referred to as a trilogy—all have love stories at their centers. In two of the three, the plot hinges on a man’s misperception that his romantic interest may be more promiscuous than she is; in the third, the legacies of the sexual revolution are explicitly debated. Stillman’s young men are shown to have undergone personal growth when they prove capable of behaving decorously toward—and, crucially, protecting the sexual purity of—his young women. Sometimes a more expansive vision of sexual agency is floated, only to be rejected in favor of traditional values.

That conservatism extends beyond Stillman’s vision of romance, and into all aspects of his films, which at once poke gentle fun at the unexamined beliefs of what a character in Metropolitan calls the UHB (Urban Haute Bourgeoisie), and endorse those beliefs. Debutante balls are presented as an antidote to social atomization. Business-minded self-help books are held out as solid guides to life. Prayer works. Anti-American sentiment is aired by characters who later decide they do like hamburgers, and want to be American, after all.

Stillman’s movies, always charmingly at odds with their times, seem to have acquired a new resonance these days—just in time for their upcoming screening at Metrograph. When I was invited to interview him in advance of that screening, it felt like an opportunity to investigate some of the ideas that have nagged at me as I’ve watched, and loved, his work over the years. So, in the hopes that Schwartz was right, and that Whit Stillman is in fact a Whit Stillman character, I asked him some questions about the ideologies under (and sometimes above) the surface of his films.—Rebecca Panovka

WHIT STILLMAN: This screening at Metrograph is for two films, Metropolitan and Barcelona. An interesting thing about it is that both scripts overlapped; I actually started writing Barcelona first, and was too intimidated by how complicated it would be to do a first film set abroad, and I’d need backers to do that. Metropolitan was more the kind of thing you could do yourself. I put aside the Barcelona script and started writing Metropolitan. But I had a day job, so I was only doing it in fits and starts.

REBECCA PANOVKA: What was your day job?

WS: At the time I was writing Barcelona, I was a sales agent for Spanish films. And because I sold other films, I knew people, I was involved with their films. I was cast in this film by Fernando Trueba. I played Dr. Mortimer Peabody, a reactionary American psychiatrist, who’s the love rival for the Spanish star Óscar Ladoire. It was a really good opportunity because I got to be on set, in Madrid, the whole summer.

RP: There’s a lot of talk about sales and the theory of sales in Barcelona. Taylor Nichols’s character, Ted, reads Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People and Frank Bettger’s How I Raised Myself from Failure to Success in Selling, and regards them as serious philosophy.

WS: Yeah.

RP: Is that material autobiographical?

WS: Very much so. I think it became more intensely autobiographical when I had to try to raise money, because when you’re raising money you’re essentially selling an idea. You’re kind of selling nothing. And it’s very hard. That’s when I started reading sales manuals. I was also reading those books for selling Spanish films. And I really liked them.

So, I was working on that Barcelona script and thinking maybe it’s too ambitious. And I switched, I got the Metropolitan idea. By then, I had taken over an illustration agency my uncle had started—he died very sadly in the summer of 1984. They were representing really good illustrators, a lot of people doing New Yorker cartoons and covers, including two artists we’ve lost recently, Jean-Jacques Sempé and Pierre Le-Tan. But there was no one in the family who could keep this company going. So I took over this agency. I was working there during the day, and trying to do the Metropolitan script early mornings, late nights, weekends and vacations.

I ended up doing Metropolitan with some money that I had, and that friends invested, and a producer friend put in, Peter Wentworth. We started out with $50,000, and then the shoot was $97,000, and I think we got up to like $200,000 before we were able to start showing the film. So, what they call the negative costs for Metropolitan, to get it in the can, was $230,000. And then, everyone turned it down, no festival wanted it, the usual stuff. We had some good people helping us. Ira Deutchman, a New York film guy, got into the back door of Sundance after we’d been rejected, and into New Directors, although they initially didn’t want us, and then a section of the Cannes Film Festival. And it all went really well. It was like a Cinderella story with Metropolitan.

A great guy at this wonderful company that I didn’t know about—Castle Rock Entertainment, which was formed out of the movie Spinal Tap (1984) by Rob Reiner—became interested in Metropolitan. And he and Castle Rock backed Barcelona. There was this wonderful meeting about the Barcelona script at Castle Rock, and their sort of script guru, script kibitzer, was saying, “Oh, this character is reading these self-help sales manuals and we’ve got to show that these kinds of things are just BS. And he has to learn that it’s just BS and reject that.” And I said, “Well, I don’t think they are BS. I mean, I think there are good books and bad books, and self-help books, some are really good. Dale Carnegie’s really good. [Peter] Drucker is good.”

The head of Castle Rock, the President, Alan Horn, who had a business background, said, “No, I agree. It’s not just ridiculous. There are some really good business self-help books...” Alan Horn went on to be the head of Warner Brothers Studios and Disney Studios. I guess that’s a good endorsement for self-help books, the right ones.

RP: Metropolitan, Barcelona, and the third film in the series, The Last Days of Disco, all situate the viewer in highly particular moments in time. What’s it like returning to them today, in a very different historical moment?

WS: Well, you can look at films with a critical eye, a skeptical eye, or just a sort of sit-back-and-enjoy-it eye. I think one of the problems with the world of cinephiles and critics and reviewers is they come to judge. I noticed this when I had a film that really struggled, Damsels in Distress. Some people were evaluating it as if there’s a checklist of things that movies should have. Does it have narrative momentum? Does it have a plot; is the story compelling? And actually, each film, if it’s doing one thing, it’s not doing another thing. So having a checklist of the 50 things it should be doing is mistaken because it just needs to be doing some of the right things in an adequate way. Damsels in Distress was doing silly things, funny things, and also philosophical things and musical things, but it wasn’t doing narrative and plot things, really.

I can look at the films and be very critical and think, how awkward, and what a mess, and gosh, you know, I was really slapping this together. Or, what I mostly do is just enjoy them. I see them again and again and enjoy them, rather than being hypercritical of all the mistakes we made.

RP: In Metropolitan especially, many of your characters are a little aimless, unsure what they want to do with their lives or their spectacular educations and maybe convinced they’re going to be failures—

WS: It’s not really aimlessness. I mean, I think what’s interesting dramatically is crossroad periods in people’s lives. I was in the throes of Erik Erikson in the college years—Youth, Identity and Crisis is one of his books. And it’s sort of like how you find the path in different stages of life, how you go from one stage to another successfully and find your role.

RP: How did you find your role, as you say? Did you always know you wanted to be a filmmaker?

WS: I was actually in a really bad Harvard interview, desperate to get in. And I didn’t go to a school that was well known for its scholars. The Harvard guy was some sort of sports recruiter. He was only interested in our school for the soccer players, so he was totally bored listening to this non-jock person. I was telling him what I wanted to do with my life, just essentially my father’s would-be career of going to Harvard, and then law school, and being in politics and getting elected to something, public service and all that, blah, blah, blah. And when I was saying this, I was thinking, “Actually, I don’t think I want to do that anymore. I really want to be F. Scott Fitzgerald!” I was in the throes of F. Scott Fitzgerald novels, which is pretty apparent in Metropolitan.

So, I wanted to be F. Scott Fitzgerald, but I had made that decision. And then at Harvard, I did The Crimson, I wrote the Hasty Pudding shows, and I tried to do fiction. But I realized that I wasn’t cut out to do fiction, or have a solitary life. I liked being with people. My favorite thing in The Crimson was being the night editor, which is sort of like being the director. I thought, “Gosh, if I’m not cut out to be a novelist, maybe I could be in film or TV?”

RP: Did you conceive of Metropolitan, Barcelona, and The Last Days of Disco as a triptych in advance?

WS: That was an afterthought. I was in the thrall of Balzac novels—and I think also he started writing books and then decided to make it a world. It was only when doing Disco that it occurred to me that one of the things that set apart these terribly popular nightclubs is that you run into people from all different phases of your life who end up going through them. It seemed cool, the idea that the Metropolitan crowd is there, and the people who are going to be the Barcelona crowd are there.

RP: Your work engages with religion, at times sincerely and at times a bit ironically or humorously. How do you think about the role religion plays in your characters’ lives, and in your films?

WS: Well, I try to have it in the films. And I want to make a super religious film set in Jamaica with really religious people. I’ve sort of gotten weirded out by what I see religious people having done in the last 10 years. So I’m less confident about it as a subject.... I guess it’ll be there in my future projects, but I’ve kind of taken the wind out of my religious sails.

RP: In some of the funniest, most fascinating moments in your films, your characters talk in extended monologues, dissecting some sort of ideology—sometimes it’s even the ideological subtext in a popular movie. Your movies, of course, have ideological subtext, too. To what extent is that ideology something you think about or articulate to yourself? And if so, how would you describe it?

WS: I don’t know about that. In Metropolitan, yeah, there are a lot of long talks and monologues. And there are essentially two people who have the long talks. One is the Charlie Black character played by Taylor Nichols, who is going on about the doomed bourgeoisie and downward mobility, and talking about all the sociological aspects of that kind of New York society. And then, there is the Nick Smith character played by Chris Eigeman, who’s essentially telling stories, talking about reputations and narratives.

And I had kind of an interesting experience because I was very much in the thrall of my godfather, Digby Baltzell, a really brilliant sociologist, [credited with popularizing the term WASP] who wrote great books like Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia, and I showed him the script for Metropolitan. I didn’t show it to many people. I also showed it to a friend who was trying to be a screenwriter, who condemned the long monologue that Chris Eigeman had about Polly Perkins. He said. “It’s ridiculous, you know, a five-page monologue. You can’t have that. It’s just terrible.” And then my godfather, Digby Baltzell, said, “Oh, I love that story about Polly Perkins.” That was great.

I think long narratives and monologues are okay if there’s a story. Even when they’re talking about The Graduate (1967) in Barcelona, they’re talking about the end of the movie. So it’s a narrative.

RP: I’m also thinking about the Lady and the Tramp conversation in The Last Days of Disco.

WS: Well, that directly relates to story because that is the narrative of Lady with this mongrel, criminal dog that she unfortunately gets involved with when she has this lovely Scotty dog living next to her, and how that is not going to work out with Tramp. Anyone knows that. That was so much fun. At that point, I had two small children, so I was just drenched in Disney films.

RP: I guess what I’m asking is, you’re obviously thinking about other films in terms of the ideology they broadcast—

WS: Yeah.

RP: Do you think about your own films that way?

WS: I don’t know. I mean, yes, yes. But I don’t know what to say about it.

This fellow Ira who helped us a lot on Metropolitan, when he first read the Barcelona script, he was really negative—you know, as negative as you can be when you’re lying about how much you like someone’s script. He said it was too on the nose politically. And a friend who saw earlier cuts, he said, “No, this is too political. It’s like a gun going off.”

And Rob Reiner, when we showed the longer cut of Barcelona at Castle Rock, Rob Reiner confronted me after the screening and said, “Is Barcelona really that way?” Fortunately, a friend of my wife’s from Barcelona was at the screening and she said, “Yes, I was just in Barcelona and that’s exactly the way it is.” And so, it was like the Marshall McLuhan thing in the Woody Allen film, where the witness comes and defends you.

But the consensus was that the long cut had too much politics at the end, and it was a little bit one-sided. And so, we did cut all the last terrorism and political stuff at the end.

"I wanted to be F. Scott Fitzgerald."

RP: What was there before?

WS: Oh, this whole other thing where someone gets shot, and a whole other terrorist thing, and more stuff, it kept going on and on. I think it’s in the Criterion DVDs extra scenes.

RP: The politics in Barcelona have aged really interestingly.

WS: It’s worked well. I mean, I’d really like people to do more with the film because the whole debate about NATO, the importance of NATO, has really come to the fore. And I see now that Spain is one of the worst countries as far as not helping Ukraine, which is par for the course.

RP: Your films are concerned with the breakdown of manners and mores—

WS: Well, you know, this whole thing of “comedy of manners,” I hate the term because people think that’s something like Emily Post, you drank out of the finger bowl or you put the napkin in the wrong place, you used the wrong fork or something. We had Stephen Fry in the Love & Friendship (2016) shoot—he knows tons about Jane Austen, so we had him do a sort of interview about Austen, which we’re putting it into a documentary. And he says “comedy of manners” is actually “comedy of morals.” It goes back to mores, in Latin. There’s a lot about romance, identity and morals in the films, you know?

I think both René Clair and Sydney Pollack address the question: are you a comedy person or are you a drama person? Sydney Pollack put it in terms of is it going to be a love story or is there going to be a gun?There always has to be a love story of some kind in my films. I’d also like to have maybe some swords, at least, if not a gun. But René Clair said: do you do comedy or do you do drama? It’s like, are you blonde or brunette? It’s like your nature. For me, there has to be a romantic comedy element. And for me, that’s identity—who you choose to be with is very important for your identity, as well as the work you choose, and what principles and ideals you choose.

RP: In addition to the breakdown in manners and mores, your films are heavily concerned with social atomization and the loss of traditional gender roles and identities. Do you think of yourself as a conservative filmmaker?

WS: It doesn’t matter how I consider myself. I try to make the films fair, so that someone can come in and interpret it as criticizing or not criticizing, validating or not validating all kinds of different points of view. If there’s a debate, I try to have a fair debate. And a lot of the dialogue comes from, well, I want to say something true. I want to have the characters saying something true, so people will say, “Well, this is true.” I write this whole thing, and then the next day, I think, “There are all kinds of cases when that’s not true. And so, I should throw out that big speech I spent three days writing.” And I think, ‘“Oh no, instead of throwing out three days’ work, why don’t I just have another character who voices the rebuttal?” There are a lot of debates of that kind.

I guess one film that’s kind of fierce ideologically in a way that might bother people without realizing it is Damsels in Distress. It’s a silly comedy with all this stuff going on, but it’s this comedy that’s actually attacking viewers ideologically, and they’re reacting to the attack. I think that’s part of the reason why it has been the film that struggles, and that’s super low rated on IMDb.

RP: In Metropolitan, Barcelona, and Last Days of Disco, virginity and sexual purity are central—

WS: Really?

RP: You don’t think so?

WS: You think so? In Barcelona?

RP: In Barcelona, there’s that whole conversation about the sexual revolution and how women in Spain are sexually promiscuous.

WS: Oh yeah. They were very proud of that, the Barcelona women. They weren’t promiscuous; they were launched. They were chicas lanzadas. The Barcelona women would go to Madrid and they’d be proud of the fact that they were advanced, they were more liberated, and the people in Madrid were retro. That was the dynamic in Barcelona. I learned about that from my first, Spanish wife Irene’s milieu. She would talk about that a lot. She was from Barcelona, so she was very proud of her grouping, chicas lanzadas, which was shocking to me.

RP: Why was it shocking?

WS: Because I wasn’t lanzada.

RP: Ted says, “The sexual revolution reached Spain much later than the US, but went far beyond it… Here in Barcelona, everything was swept aside. The world was turned upside down and stayed there.” Do you think the sexual revolution went wrong, and not just in Spain?

WS: Totally.

RP: Can you say a little more?

WS: No.

RP: I guess I just notice in watching these films how explicitly sexual purity is discussed, debated, and in the end valued.

WS: I think you’re right, and I don’t think anyone’s ever said that, as far as I know. It’s sort of part of that whole “prig” conversation, right, in Barcelona? Are things upside down now or are they right? Were they upside down before and they’re right side up now? Or were they right side up before and now they’re upside down? Or some combination?

RP: And you think they were right side up before?

WS: I have no comment.

RP: In Metropolitan too, the conclusion of the movie—I don’t want to spoil it for anyone, but it has to do with protecting a character’s virginity.

WS: Well, I would say protecting from exploitation. I don’t think that’s the question of virginity or not. If Audrey and Tom are in love, that would be a different thing. It’s like, are you with a guy who is a bad guy with bad intentions, strictly dishonorable? Or are you with someone like a Charlie or a Tom who are going to probably try to be good people?

RP: People who watch these two films in a row will notice some of the same faces. How do you think about working with actors over and over?

WS: Yes. I really love that, and I don’t understand why more people don’t do it. It’s just so great. And it’s hard for me to kind of get out of it and consider other people. I just want to find parts for the people I’ve worked with. I think Preston Sturges did it, John Ford did it. It’s so logical. I don’t understand these people for whom it’s like a blank slate each time. I guess it’s because they’re financing it. They need big stars. It’s one of the advantages of smaller budget films.

RP: After you did these three films, you moved on to other kinds of work. How would you describe that trajectory?

WS: Miserable. Really miserable. I wrote this novel after Last Days of Disco. They couldn’t get the novel out before the movie came out, and they thought a novel had to come out with a movie. Jonathan Galassi said we wouldn’t have time to do the novel before the movie comes out, so just take your time, do a literary novel, do the best you can and we’ll publish it.

But so, you know, getting involved, there are certain projects that you sort of realize, oh, this is dangerous. This might just become a time suck, derail your momentum. I think if you’re going to do the more ambitious projects, the more expensive things, have some tiny budget project too, write some script that’ll be tiny budget so that when the big expensive thing doesn’t happen, you have something to do, and that you can get off the ground on your own terms.

RP: Anything else you would like readers or viewers to know?

WS: Well, let’s see. So the Metrograph screening is kind of cool and key because of the double feature nature of it, which is rare. It’s very rare to show Metropolitan and Barcelona. It’s part of this thing we’re doing this September, going on tour to different places, Princeton, Yale, Cornell, Bedford, Columbia, and Bryn Mawr. It’s a fun thing to come out of the pandemic, to be able to show the film in cinemas. Lately, I’ve just been going to see films all the time here in Paris because they get all these old films re-showing, and it’s great to have the cinema experience back. We were really worried during the pandemic that cinema culture was going to die. I’m really hopeful it’s going to come back very strong.

Rebecca Panovka is a co-editor of The Drift.