Columns

Wardrobe Department: Tabea Blumenschein

On the fearless sartorial artistry of the German underground icon.

Ulrike Ottinger: From Paris to Berlin plays at the theater from Friday, October 3, and streams At Home from October 1.

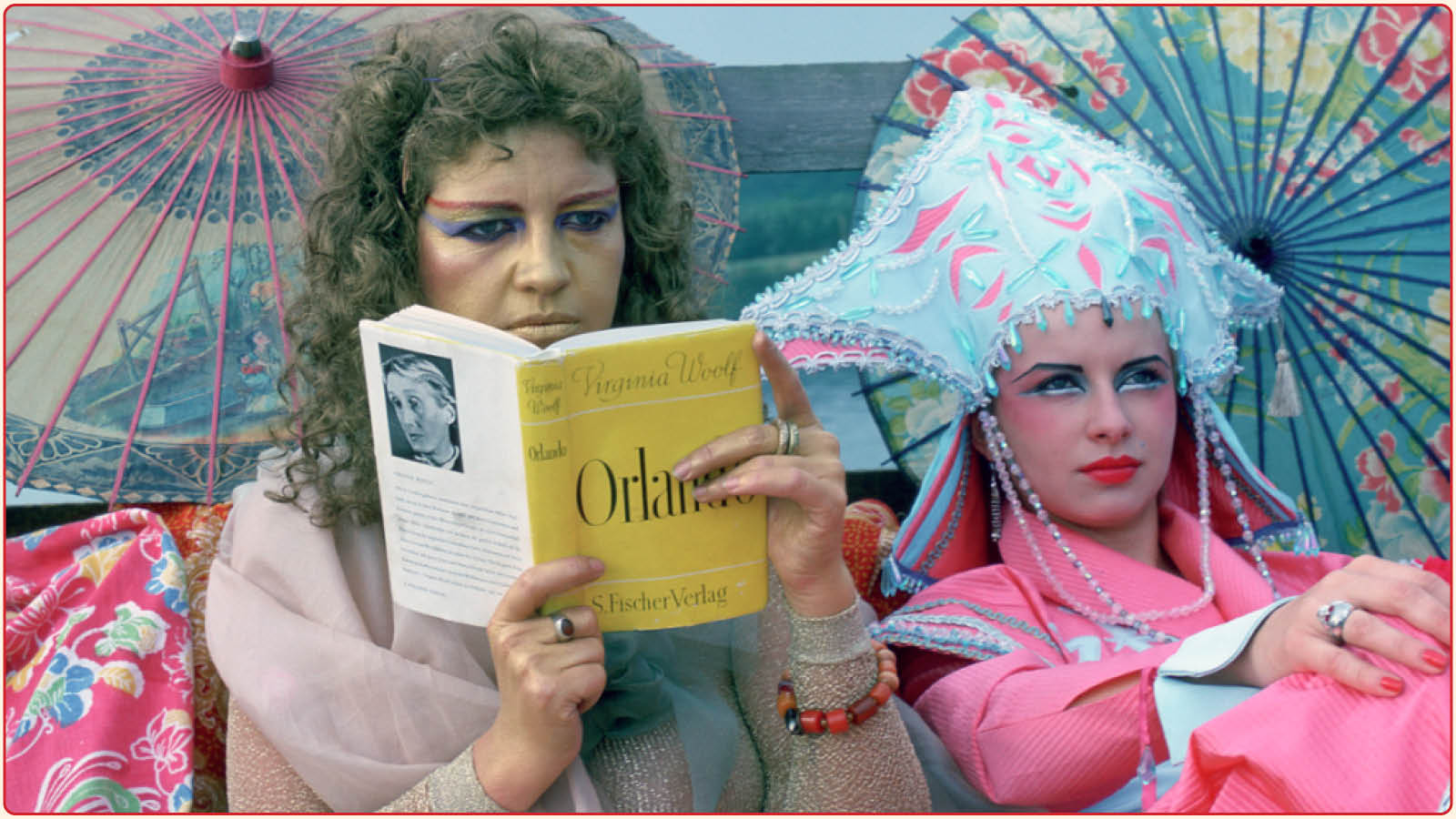

Young Tabea Blumenschein and Wolfgang Müller in West Berlin (1980s).

Share:

Few screen presences rival Tabea Blumenschein’s, with her statuesque composure, porcelain-doll visage, and unflinching blue-eyed gaze. Her striking appearance and bold aesthetic vision, especially as a costume designer, centrally informed her film characters, who often became costumed concepts: walking metaphors in living color. This is perhaps most vividly displayed in Ticket of No Return (1979), where Blumenschein’s unnamed protagonist arrives in Berlin determined to drink herself to death. Entirely silent, she speaks only through her movements, expressions, and most conspicuously, her wardrobe. She arrives in scarlet eyeshadow and matching coat with a high funnel-neck collar, gliding through the city like a peacock on parade; and for a meta-Greek chorus of judgmental women—including a sociologist, a psychologist, and a common-sense moralist—she becomes the subject of relentless scrutiny. Costumes shift from scene to scene with no narrative explanation or temporal logic. At one moment, she’s in an oversized black bow and cylindrical gold earrings; the next, she’s a butch leather daddy, complete with trimmed mustache and plaid shirt. Later, she appears in an oversized schoolbus-yellow blazer with ivory lapels and a matching pillbox hat, perched atop a dotted chiffon scarf that’s wrapped around her head. These kaleidoscopic transformations refuse coherence, and by extension, the kinds of moral legibility that the chorus—and the viewer—may be seeking.

This refusal to be pinned down defines Blumenschein’s entire artistic life: as actor, costume designer, illustrator. Whether sculpting her persona on screen or reimagining femininity in her drawings, she turned her radical project of self-styling into a lifelong experiment in queer defiance. If her legacy endures unevenly in English-language film history, it is not because her contributions were small, but because they were interdisciplinary, queer—and fiercely Berlin.

Ticket of No Return (1979)

Blumenschein’s collaboration with filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger—her former partner and most trusted collaborator—marked a defining phase in her artistic development, resulting in some of her most memorable cinematic work. Under Blumenschein’s sartorial direction, costumes are not merely embellishments, but unconventional tools of experimentation. The garments in Ticket of No Return are excessive and symbolic: the wool red coat gestures to glamor and spectacle, while her cut-out metallic silver getup embodies eroticism and destruction. Alcoholism and aesthetics form a fatal symbiosis, and her ever shifting wardrobe both masks and magnifies her unraveling, preserving the idea of beauty even as it flirts with self-annihilation. Her costumes act as both a cover for her self-destruction and a way to openly display it.

Madame X: An Absolute Ruler (1978), also directed by Ottinger, offers an equally vivid example of Blumenschein’s radical costuming and performance practice. The film follows a pirate queen who lures women from all walks of life (including Yvonne Rainer) to join her on a fantastical ship. Onboard, Blumenschein morphs into a series of surreal archetypes: feathered and mirrored headpieces, magenta capes, veiled pirate regalia, and shimmering gold jackets. Far from period-accurate, these costumes operate as gender-fluid fantasy, deliberately estranged from historical realism, as if asking viewers to reconsider the constraints that clothing usually places on time and identity. Ottinger’s shots are meticulous and her camera luxuriates in the textures of clothing, like fashion photography but with theatrical rather than aspirational intent. Meanwhile Blumenschein channels kabuki, clowning, burlesque, and Brecht, sometimes all at once, reflecting Ottinger’s own complicated habit of borrowing and fetishizing Asian culture, and in both films, clothing becomes a site for pleasure and defiance. Silk robes and painted faces signal a kind of cosmopolitanism and hybridity, but at the same time risk reducing non-Western traditions to exoticize flourishes. That tension is in some ways part of the charge; Blumenschien’s costumes, at once rebellious against bourgeois taste and complicit in Orientalist fantasy, stage the contradictions of the films themselves.

Madame X: Absolute Ruler (1978)

The art historian An Paenhuysen has argued that Blumenschein’s drawing practice—especially her series of androgynous hybrids, pin-up creatures, and sailor girls—offers a kind of visual lexicon for these cinematic transformations. Many costumes first appeared as sketches or doodles, scrawled with sardonic captions, before blossoming into full screen fantasies. In 2022, two years after Blumenschein’s death, the Berlinische Galerie mounted Zusammenspiel (“Interplay”), the first major exhibition to showcase her graphic oeuvre, foregrounding the works alongside Ottinger’s photos. There’s an anecdote Ottinger tells in the exhibition catalog, where she describes Blumenschein as having an enormous gift for mimicry, likening her to Silent film-era actors who could summon entire personalities without a word. The two would workshop outfits and characters in Ottinger’s studio, photographing each other in full looks, long before filming began. A kind of visual pre-writing, these sessions became an essential part of the DNA of the films they made together. What emerges from these stills is the intimacy and co-authorship between the two women, and it becomes clear that the fashion was a generative exercise in storytelling. The catalogue, which gave Blumenschein long-overdue recognition, reveals her not just as a muse but as a co-author of Ottinger’s most indelible images. It also foreshadows a broader opening of her archive, which includes illustrations and costumes.

Blumenschein’s films resist a certain narrative closure and embrace contradictions, as did her life. Offscreen, she favored heavy eyeliner and bubblegum pink lipstick often contrasted sharply with leather, drag, and what friends called her “billboard” T-shirts, emblazoned with slogans like “Barbie” or “Butch on the streets, Femme in the sheets.” A strikingly pretty woman who chose not to be conventionally pretty (at least not always), Blumenschein dressed with a defiant performativity that mirrored her work. Born in 1952 in Rietheim, she studied fashion and painting at the Kunstschule Konstanz. In 1973, she moved to Berlin, and quickly embedded herself in the alternative art scene, which at the time was undergoing a self-conscious fragmentation into collectives, bands, fanzines, and guerilla filmmaking.

Her biography unfolds in moments of high visibility and then none at all. No books have been written about her. Some things we do know: inventive costuming for other filmmakers like Walter Bockmayer; her moment in the experimental artist collective Die Tödliche Doris (The Deadly Doris); a relationship with Patricia Highsmith; downtown wanderings with Cookie Mueller during her stint in Berlin; rubbing elbows with Martin Kippenberger; collaborating with knitwear designer Claudia Skoda. For those steeped in queer and subcultural history, these references are resonant, but they do not sum her up. She was, like Ottinger’s films, a collage.

Madame X: Absolute Ruler (1978)

Her time with Die Tödliche Doris was instructive. Wolfgang Müller recruited her into the anarcho artist collective in 1980, calling her “an extreme beauty with an incredible presence—and yet very stubborn.” While often recognized as a band—albeit one that made music purposely harsh on the ears—Die Tödliche Doris was ultimately an immersive, art project that blurred forms and genres. With a rotating cast of members, Doris was adaptable and amorphous, like its amoeba mascot, producing/generating records, films, books, live concerts, and ballets. Müller has said that “Doris has clothes to thank for her existence,” and that can be attributed to Blumenschein’s work, which deconstructed punk’s visual codes, subverting aggression with a measure of absurd fetish and folkloric kitsch. Crucifixes and mohawks abound alongside ditsy florals and sheer capelets. In a performance at The Kitchen in New York, religious vestments with oversized crosses were paired with spiky high heels. She reimagined the feminine not as object but as grotesque mascot, a tactic that might have felt at home in early works by Leigh Bowery, but with a distinctly German flavor of self-satire.

It was during this time, too, that Blumenschein’s illustration practice deepened as an extension of the same project: using visual language to question, distort, and remake the self. The colorful feminine drawings from art school gave way to bearded ladies, and then sailor boys that retained the same features, like pouty red lips. In her drawings, as in her performances, she refused the idea of a single, stable identity, sketching new avatars that could mutate at will. Gender, in her work, was ornamental, fluid, and always up for re-design. Resisting realism, and at least responding partly to the authoritarianism of postwar fascism, her work refused gender binaries, using aesthetic fusion to rebuke a divided Germany, and enacted desire as a material force—all with a sense of playfulness.

By the 1990s, Blumenschein had largely disappeared from the public eye. She retreated from film but not from art—moving more privately through Berlin, living in a prefab tower block where she continued working across illustration, sculpture, and performance. But Tabea never domesticated, even in her final years joyfully suspicious of systems that asked her to behave. Her comic Matriarchat Marzahn, completed in her final years while living in East Berlin’s high-rise district, is a tragicomic saga of punk matriarchy and domestic anarchy, reimagining the neighborhood as a utopian island where subculture reigns (a world not so distant from Blumenschein and Ottinger’s cinematic dreams). In a rare interview, she dryly rejected the suggestion that she might take up gardening or easy leisure in old age. “I’m not an old lady who wants to walk in the park,” she said, “I’d rather work.” She didn’t own a smartphone; she refused the internet. Instead, she printed photographs by hand, cut and pasted them into vibrant collages, and made elaborate zines and artworks that functioned as analog Instagram. The visual diaries of her private life seem less like acts of nostalgia than declarations of autonomy. She was still punk, in practice if not in fashion, and she never fully withdrew from people’s imaginations. Blumenschein was likely the last great love of famously depressive novelist Patricia Highsmith, who was so smitten that she once kept a dirty bathmat from a shared hotel room as a memento. When Tabea ended things with a brief note (“My relationships never last longer than four weeks”), Highsmith was devastated. Decades later Blumenschein sent Highsmith a German-English dictionary, a photograph, and a warm letter signed “All my love, Tabea.” Blumenschein, it seemed, didn’t disappear from people’s lives but stayed lodged somewhere.

After her death in 2020, her vast archive has begun to resurface, not as memorabilia but as a memoir. A lifetime of provocative resistance that insisted on this: not everything belongs to the timeline. Not everything needs to be shared. But it all should be worn.

Tabea Blumenschein

Share: