Twentynine Palms (2003)

Columns

Strange Pleasures: Twentynine Palms

Strange Pleasures is a regular Metrograph column in which writer Beatrice Loayza shares unconventional desires found across underground and mainstream cinema alike.

Alt Divas: Argento / Dalle / Golubeva screens at Metrograph from Friday, November 7.

Share:

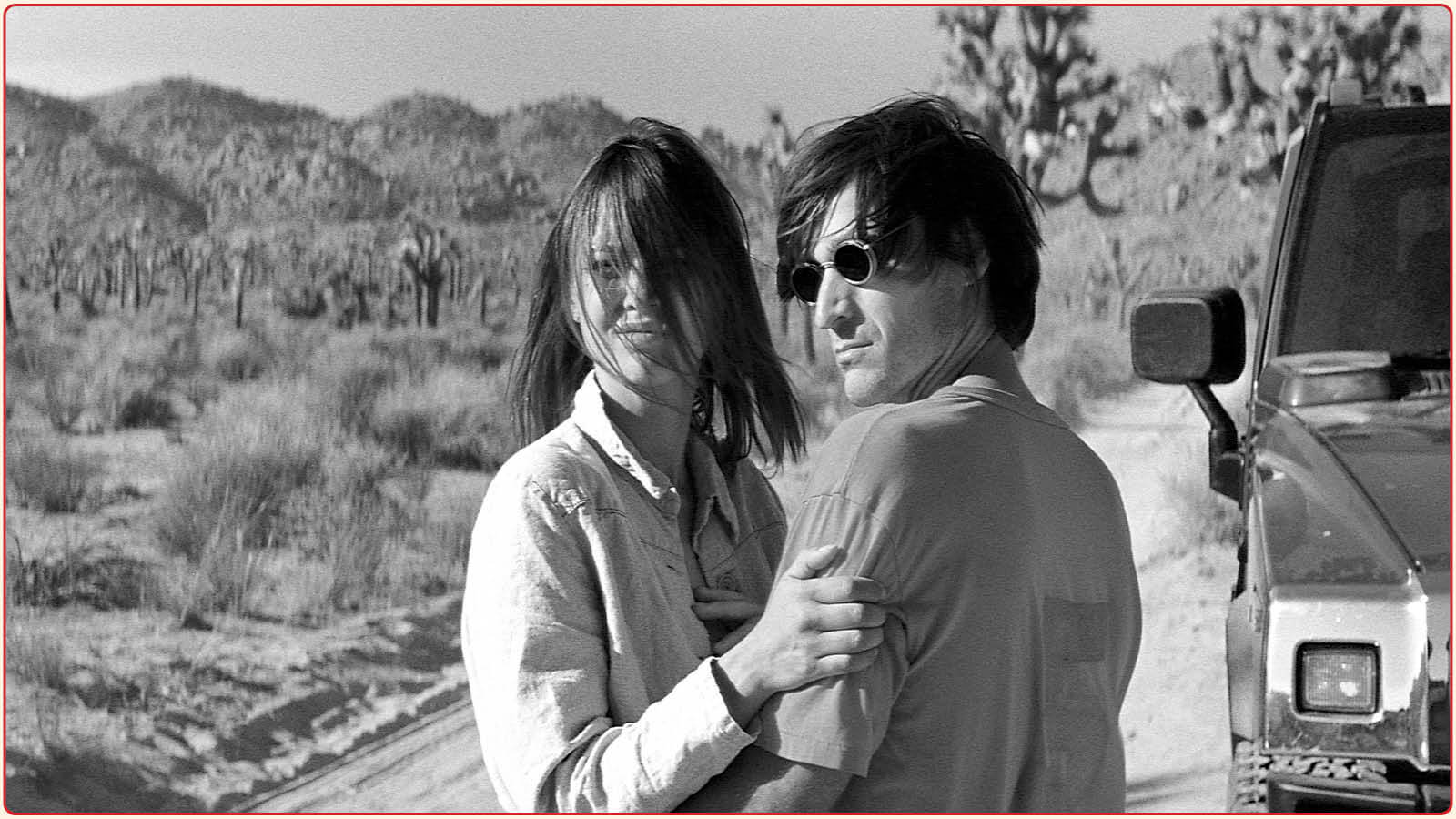

“YOU SEE, WE’RE NOT ALONE,” murmurs Katia (Yekaterina Golubeva) as a vehicle with tinted windows drives past her and her American lover David (David Wissak) halfway through Twentynine Palms (2003). The couple, a louche photographer and his Russian girlfriend, are ambling around Joshua Tree, location-scouting for his upcoming gig, while screwing around—and screwing each other—against the backdrop of a desolate landscape too vast and quiet for their own good. When the car appears out of nowhere and moves past the two mid-embrace, there’s nothing concrete to suggest they’re in danger. Yet their solitude and the setting’s uncanny silence intermingles with their sexual charge to create a mood of heightened vulnerability not unlike slasher scenarios in which carnal abandon attracts punishing violence. Twentynine Palms, the third film by the philosophy teacher-turned-filmmaker Bruno Dumont, strips this genre dynamic of its moral underpinnings but preserves its ambient unease, making even the most innocent bursts of action that punctuate the film’s listless proceedings feel threateningly ambiguous. Withholding legibility allows Dumont to create a lawless theater dictated by whim and instinct, free to the point of abjection through the director’s characteristically nihilistic gaze.

Katia and David don’t really understand each other. Katia, who is Russian, doesn’t speak English and communicates with David in broken French, and David’s French is even worse. Their relationship is built on physical intimacy, which feels particularly electric because of the language barrier, if also fraught and uneasily obscure. Can consent be intuited? In the opening scene, we see David driving down the open road in a red Hummer, the soothing twang of a country track combining with the crunching sound of turning rubble. Like a kid, Katia has been sleeping in the backseat, her voice mousy and distant as she’s roused into consciousness. Their dynamic is immediately apparent: here is a hot-tempered artist in a cartoonishly macho vehicle and behind him, his seemingly meek foreign girlfriend. Their sex would seem to reaffirm this image when, for instance, David swims toward Katia in their motel pool like a predator and forces himself into her; or when they venture out into to the wilderness and, per David’s bidding, fuck doggy-style with Katia stabilizing herself against a boulder.

“Nothing happens, man; it’s just a lot of people going nowhere,” said Mark Frechette, star of Zabriskie Point (1970), of Antonioni’s film, another European take on the metaphysics of the American desert, brimming with anger and ennui. The same can just as easily be said of Twentynine Palms, a clear descendant of that modernist hippie movie (that David is a photographer also seems to be a nod to another Antonioni classic, 1966’s Blow-Up, also about staring through a lens and finding death). Likewise, Dumont doesn’t care to structure his Californian mood piece with boldfaced motivations and narrative footholds. In an interview, he likened his approach to the transition from “figurative to abstract painting.” In other words, his proportions are key. His subjects are rendered banal, their actions, purely expressive in the context of their epic surroundings: it helps that all these characters seem to do is fight and fuck.

Twentynine Palms (2003)

Their bodies are insignificant next to the southern California desert’s infinite open roads and colossal rock formations, yet also strangely liberated and unselfconscious, which might explain David’s fixation with public sex. Nevertheless, the film’s seemingly straightforward depiction of dominance and submission is enriched by Golubeva’s performance. Katia, in her hands, finds pleasure in playing the subjugated; she’s aroused by David’s hunger and brutish audacity, if also disgusted (he nearly drowns Katia by demanding an underwater blowjob) and amused (fucking on the boulder does nothing for her and prompts a giggle fit). Golubeva died shockingly young in 2011 with a small but mighty handful of credits to her name, among them her former partner Leos Carax’s film Pola X (1999) and Claire Denis’s I Can’t Sleep (1994). These works also treat Golubeva’s wobbly French skills as a virtue and rely on her image as a beautiful and opaque outsider to create intriguing tensions.

Despite ostensibly playing the dominant partner, David is also bothered by Katia’s cryptic demeanor, her penchant for walking barefoot, her meandering observations, and passionate mood swings. The balance of power also, oddly, seems to flip when David orgasms, his exclamations so wild and weepy that he seems on the verge of shouting, “Mommy!” Physical chemistry anchors their relationship, but as they continue wading through the uncanny valley, whatever truths lie in good sex are muddled by the couple’s emotional frustrations—by the sense that something, somewhere is wrong and it’s the other person’s fault for being withholding, or otherwise not making any sense.

Before Twentynine Palms, Dumont had made two emphatically feel-bad movies set in northern France: La vie de Jésus (1997) and Humanité (1999), both about gloomy provincials whose mundane surroundings generate despair as well as a taste for mindless brutality. Twentynine Palms extends upon this stark existentialism. Dumont’s enduring fascination with the mythologies perpetuated by American culture also clarifies the film’s allegorical vision: a kind of cosmic exploration of violence through the lens of a countercultural Adam and Eve. Dumont’s most recent feature The Empire (2024) is a spoof of Hollywood-style space operas like Star Wars (1977), where the forces of “Good” and “Evil” are revealed to be completely arbitrary. That new film is rooted firmly in the comic mode that has distinguished Dumont’s work since the sharp turn that came about with 2014’s Li’l Quinquin, yet its conceit also echoes the director’s preliminary ideas for Twentynine Palms: namely, a desire to engage with American cinema in such a way that implodes its popular styles and narratives.

The Empire sees a tragicomic vacancy in spectacular shows of justice-seeking. Likewise, Twentynine Palms, if anything a relationship drama (or anti-drama) for the bulk of its runtime, sees death at the core of its swirling desires; destruction at the heart of its characters’ hopeless search for one another.

The finale—a rape scene that recalls Deliverance (1972), and a hotel murder that employs a knife (as well as a disturbed masculine ego) in the mode of Psycho (1960)—is meant to feel blank, even as the carnage, for all its bloody spontaneity, has from the beginning always seemed like a latent possibility. When, in the final shot, we see David’s naked corpse sprawled out in the desert, you get the sense that he’ll sink into the sediment—extinguished by his own irrational urges and pulled back into the dirt, traceless.

Twentynine Palms (2003)

Share: