Column

strange pleasures: patrick swayze

Point Break (1991)

Column

BY

[wpbb archive:acf type=’text’ name=’byline_author’]Beatrice Loayza

Strange Pleasures is a regular Metrograph column in which writer Beatrice Loayza shares unconventional desires found across underground and mainstream cinema alike.

Lazy, Hazy, Swayze Days opens at 7 Ludlow on Friday, July 19.

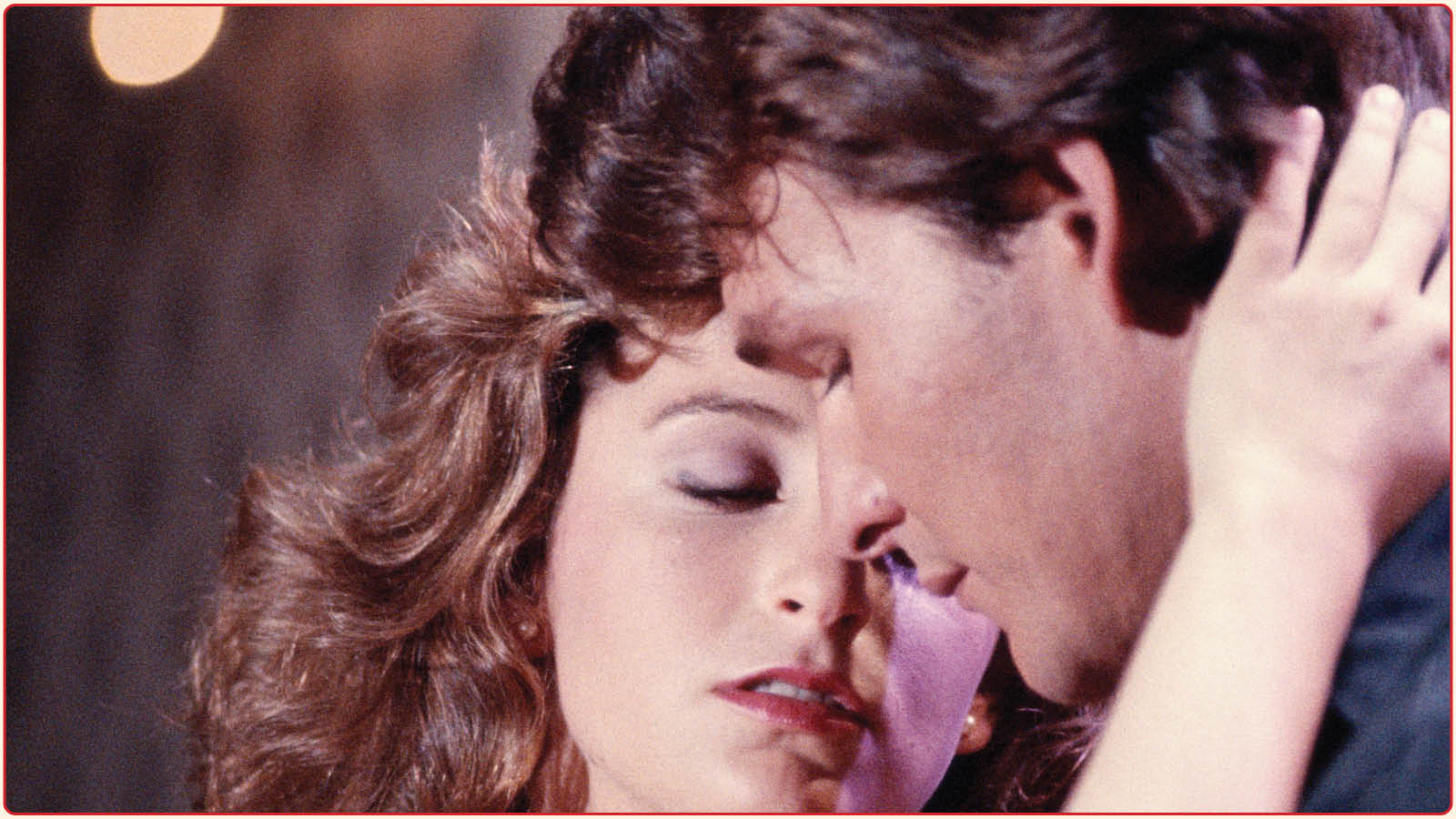

When Patrick Swayze moves, we like to watch. In Dirty Dancing (1987), 17-year-old Frances “Baby” Houseman (Jennifer Grey), her mouth agape, fades into the background when Swayze’s Johnny Castle hits the dancefloor for the first time. His passionate mambo scatters the crowd. When Swayze as James Dalton, the lead bouncer at a skeevy gin joint in Road House (1989), takes out the proverbial trash, Elizabeth (Kelly Lynch), the dreamy doctor who becomes his love interest, grips a wooden post, her lips trembling as she takes in the sight of her man beating shit-stirrers to a pulp. Then there’s the scene that introduces us to Swayze’s bank-robbing surfer Bodhi in Point Break (1991). Twinkling synth tones announce his arrival as if he’s an otherworldly being descending upon us. Bodhi emerges from his liquid cave, cutting through the tide, his hand grazing over the ripples of the current, literally stopping Keanu Reeves’s undercover agent Johnny Utah in his tracks.

But it isn’t just that the actor also happened to be a ballet dancer, martial artist, and former football player, and that, as a result, he could play bonafide bruisers and hip-swinging heartthrobs alike with a natural ease. There’s something specific about his grace, his physicality-and the way they were employed in his early, star-making roles-that sets him apart from the era’s other studs. He wasn’t an arrogant punk (Tom Cruise); not a boy-next-door (Michael J. Fox) nor a tortured anti-hero fending off femme fatales (Michael Douglas). In the ’80s, sex entered the mainstream in the form of erotic thrillers and teen sex comedies that made spectacles of libidinous dames and wary virgins; but Swayze’s contributions to this uptick in lusty content centered him as a wondrous object of desire, a status achieved by the rugged sensuality of his acrobatics. To his dancing, he brought a deliberately masculine bravura, a sweaty, blue-collar viscerality, while his fights were made passionate and primal by his dancer’s grace and internal tempo. Swayze’s unconventional upbringing-his father was a one-time rodeo star; his mother, a dance instructor and choreographer-no doubt helped.

Born and raised in Houston, Texas, Swayze became a glossy, modern manifestation of Southern chivalry: he called himself a “peaceful warrior.” His agent during the first decade of his movie career notes in a revealing anecdote that even as his star was rising, Swayze maintained the habit of calling other men “sir.” Swayze explained himself: “You hold the door for women, you pull their chair. It’s your job, it’s not a macho thing.” He added, “If you say ‘sir’ in a different context it can also be very dangerous. ‘Sir, you mess with me one more time and I break every bone in your body.'” This fraught old-school gallantry was complicated by his expressive physicality and its alignment with traditional conceptions of gender roles. He possessed an action hero’s red-blooded swagger and principled vigilance, sans the strongman rigidity of a Schwarzenegger or a Stallone. His form of “action” encompassed battering, grooving, and making love, which turned out to be quite an irresistible formula at a time when the increasingly liberated, 9 to 5 career woman could more openly crave hot sex and feel empowered to voice her standards: no scumbags, no chauvinists. Gentleman Swayze struck an appealing balance.

On-screen, his violence was defensive, righteous, geared toward maintaining order and honoring his queens. See, for instance, Johnny pummeling Robbie (Max Cantor), the sleazy Yale med student who impregnates and abandons Penny (Cynthia Rhodes), Johnny’s bestie and dance partner at the upscale Catskills resort in Dirty Dancing. In the eyes of the film’s high-society milieu, men like Robbie are ideal partners for young, educated women like Baby, who dreams of entering the Peace Corps. Yet Robbie’s cruel negligence of Penny motors the film’s plot and the desperate actions of its characters: Penny only has access to an abortionist on the night of her mandatory performance with Johnny, so he must train Baby to replace her. Though they ultimately pull off the show, they return to find Penny mangled by the dodgy procedure. Penny makes it out alive, but Johnny, bristling with contempt, spots Robbie and swoops upon him with an avian ferocity: bounding over the railing of a porch, he knocks his shambling opponent back and forth, his feathery mane shaking with each lunge. The same black, ribbed tank top that vaguely resembles a leotard when Johnny’s gyrating is used here to highlight his raw power, his absence of protective armor. Robbie is covered up in a cozy white sweater, but Johnny bares his skin, and even beckons Robbie to hit him, knowing this man’s flimsy jabs couldn’t break his flesh.

Dirty Dancing (1987)

On the other hand, Swayze’s strength and supple coordination made his love scenes indelible. His touch could be tender, elegant; the kind of touch that tingles from beyond the screen. When Johnny plays sensei to Baby’s fledgling dancer, there’s a touch that plays on repeat. Johnny holds Baby from behind with one hand on her midriff and with the other, takes her arm and places it over his neck before his fingers cascade down the contours of her torso. It’s too much. She giggles. So they do it again and again. And again. Dirty Dancing, in case it wasn’t obvious, is essentially a sexual initiation drama in which Baby discovers the joys of unbridled physical expression, of which Johnny-a working-class hunk-is of course a skilled practitioner. The big move, the film’s statement set piece, however, is the lift, which Baby struggles to nail until the cathartic finale. Lifted from a stage by Johnny’s posse of dancers, Baby races down the aisle and leaps headfirst into Johnny’s arms. He grabs her by the hips and, briefly, becomes an Adonis-like statue, raising Baby directly above his head with a reverential gaze. Whereas the roguish John Travolta transmitted an urban cool, his fancy footwork better suited to neon-lit nightclubs, Swayze was a denim-clad chevalier; his courts, forest lodges and highway saloons.

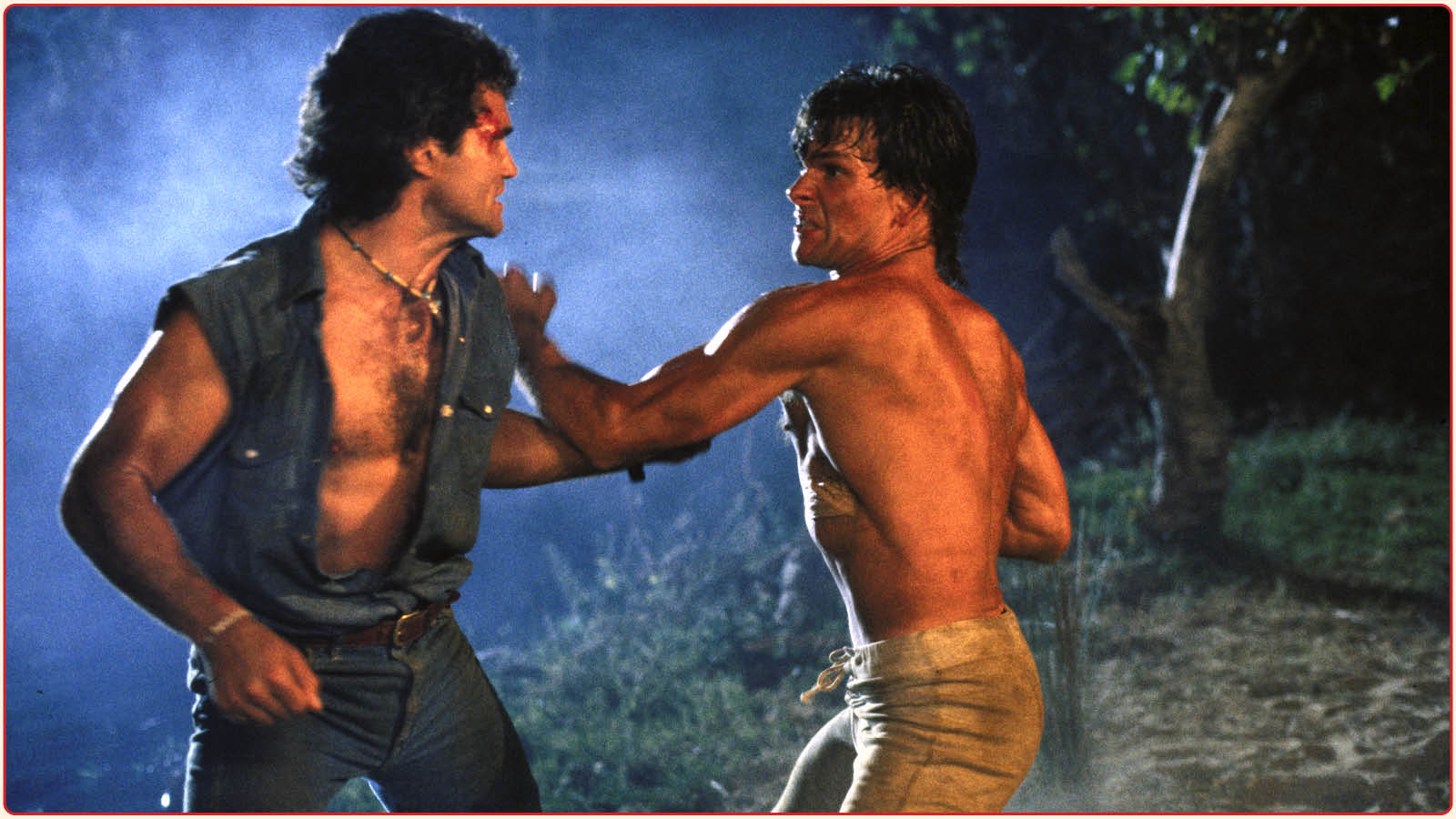

In Road House, Dalton has been hired to revamp the Double Deuce. His strategy for dealing with the pub’s troublemakers is eminently reasonable, reflecting Swayze’s professed personal codes: “I want you to be nice,” Dalton tells the other bouncers, “until it’s time to not be nice.” When that time comes, Swayze could be monstrous: consider Dalton’s shirtless brawl against Jimmy Reno (Marshall Teague), the biggest, baddest henchman of a mobster whose life’s goal, it seems, is to sabotage local businesses. The fight ends with Dalton ripping Jimmy’s throat out with his bare hands, hawk-style, after Jimmy pulls out a secret gun.

Swayze played men who could hold you, but not possessively. Because of his air of nobility, accented by his chiseled cheekbones and deep-set eyes, his touch also conveyed trust. This is why I love that pottery scene in Ghost (1990), when Swayze’s Sam (again shirtless) comes up behind his beloved Molly (Demi Moore) as she fashions a clay vase from a spinning pottery wheel. He caresses her waist, glides his hands up her forearms and makes her lose her concentration; her vase collapses into doughy mush. Then, he stretches his muscular arms forward. Slowly, sensually, he massages her hands, slathered in the viscous substance.

The pottery scene is legendary because it’s ridiculous, though Swayze knew that. Look at the way Sam bites his lip; his grin. He knew he was doing something naughty. And a little weird. But, then, the best lovers feel new things out, and there’s something liberated about that, nested in the jungles of intuition. “You’re wild,” Baby tells Johnny, laughing ecstatically. “He’s a modern savage. A real searcher,” says surfer girl Tyler (Lori Petty) of Bodhi in Point Break. Still, there’s an intelligence to Bodhi, a reasoned use of his powers, that makes him all the more formidable. During a game of beach football, eerily illuminated by the headlights from multiple cars, Bodhi pounces on Johnny Utah and eventually takes possession of the ball, grapevining through the sand and shooting out across the shore with fleet steps. Vengeful Johnny knocks him into the water, though when the other men in Bodhi’s crew surround them, peeved by the younger man’s disproportionate use of force, Bodhi smirks and shrugs it off: “Don’t you know who this is? Johnny Utah. The Ohio State Buckeyes.”

Swayze’s men knew how to restrain themselves and stick to their principles, but athletic, nimble, rugged that they were, they also (quite understandably) exhibited a certain cockiness: an overconfident sense of abandon born of their preternatural physical abilities. It’s what makes Bodhi such a believable thrillseeker or Dalton (who is “shorter” than his new colleagues had expected), comfortable taking on multiple crooks at once. It’s what makes Johnny come back at the end of Dirty Dancing: you people will watch me dance. Skydiving, stick-’em-ups? No sweat.

I can’t help but mention Swayze’s lifelong addiction to cigarettes. He claimed to smoke 60 a day, and continued the habit even after he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. In the year before his death, he reckoned with his worsening condition in a televised interview with Barbara Walters. “I want to live,” he told her. He wasn’t talking about undergoing treatments or actively fighting the disease. “You spend so much time chasing staying alive, you won’t live.”

Beatrice Loayza is a writer and editor who contributes regularly to The New York Times, the Criterion Collection, Artforum, 4Columns, and other publications.

Road House (1989)