Essay

Rosa La Rose, Fille Publique

On unsafe sex in Paul Vecchiali’s enchanting melodrama.

Rosa La Rose, Fille Publique (1986) opens at Metrograph on Friday, July 11.

Share:

The restoration and re-release of Paul Vecchiali’s Rosa La Rose, Fille Publique (1986) represents a rupture moment in contemporary cinema culture. Until relatively recently, his films have rarely been able to screen stateside and generally only the most hardcore cinephiles outside of France have had the chance to appreciate the dizzying career of Vecchiali: a Corsican-born Cahiers du Cinéma critic-turned-actor-turned-filmmaker who made nearly 30 features of his own, in addition to helming Diagonale, a pioneering production company that supported Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), Simone Barbes or Virtue (1980), and many of Vecchiali’s own films, before collapsing in the ’90s. Vecchiali is not unique among his generation of French cineastes for collapsing the roles of enthusiast, critic, producer and, ultimately, artist; consider Henri Langlois’s humble beginnings, pulling abandoned film reels out of the trash for an archive that would become the Cinémathèque Française, or Marin Karmitz’s considerably greater success as an exhibitor (via MK2) than as the director of films like Coup for Coup (1972) or Comrades (1970). But Vecchiali’s diverse portfolio speaks to his holistic obsession with pushing cinema forward by any means possible, and makes him thus even harder to pin down than his more famous Cahiers compatriots.

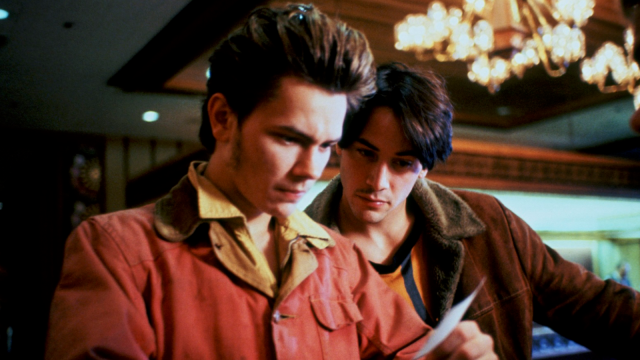

Perhaps Vecchiali’s most famous film in France as writer-director is Encore (1988), which follows a disenchanted bourgeois who tests positive for HIV, marking it as one of the first French films to acknowledge the AIDS crisis head-on. (The structure of Encore—in which 10 years of its hero’s life are broken into 10 individual scenes, each a single take, beginning in 1978 and ending in 1988—anticipates Gaspar Noé’s 2002 film Irréversible or François Ozon’s 2004 melodrama 5×2.) Immediately before Encore, Vecchiali made Rosa La Rose, which tracks a few days in the life of the eponymous sex worker played by Marianna Basler. And while nothing is extraneous in films as meticulously and elegantly constructed as Vecchiali’s, there’s a brief moment early in Rosa that speaks to the crisis that would animate Encore: our heroine is introduced as two potential johns bicker over who got to her first, only to invite the men to join her for a threesome. After all parties are satisfied, she bids them adieu: “Watch out for AIDS!” Soon Rosa is off to celebrate her twentieth birthday, which brings a chance encounter with a blue-collar laborer named Julien (Pierre Cosso) and her first taste of real love, beyond the easy-cum easy-go exchange rate of her teenage years.

Rosa La Rose, Fille Publique (1986)

She doesn’t know quite how to act around Julien, not unusual for anyone in their early twenties or unaccustomed to falling in love. But Vechialli depicts her romance with Julien as nothing short of an existential risk, upending her carefully ordered world of regulated male desires and all-too-willing performative affection. It recalls the William S. Burroughsian cut up phraseology that Orion Pictures curiously used to advertise Dennis Hopper’s not-quite-masterpiece The Hot Spot (1990): “Safe is Never Sex. It’s Dangerous.” Indeed, Rosa La Rose eagerly follows in the footsteps of many “hooker with a heart of gold” classics ranging from La Traviata to Guy de Maupassant’s short story “Boule du Suif” to Marlene Dietrich’s collaborations with Josef von Sternberg. The opening credits announce the film’s dedication to Max Ophüls and Jean Renoir, two titans of the 1930s and 1940s French cinema that Vecchiali adored, but also two still-living actresses, Danielle Darrieux and Dora Doll. The latter would play a crucial role in Encore, while Vecchiali cited seeing Darrieux’s performance in Anatole Litvak’s Mayerling (1936) when he was six years old as the moment he fell irreversibly in love with cinema (three years before Rosa La Rose, he had gone so far as to cast her in his 1983 drama At the Top of the Stairs).

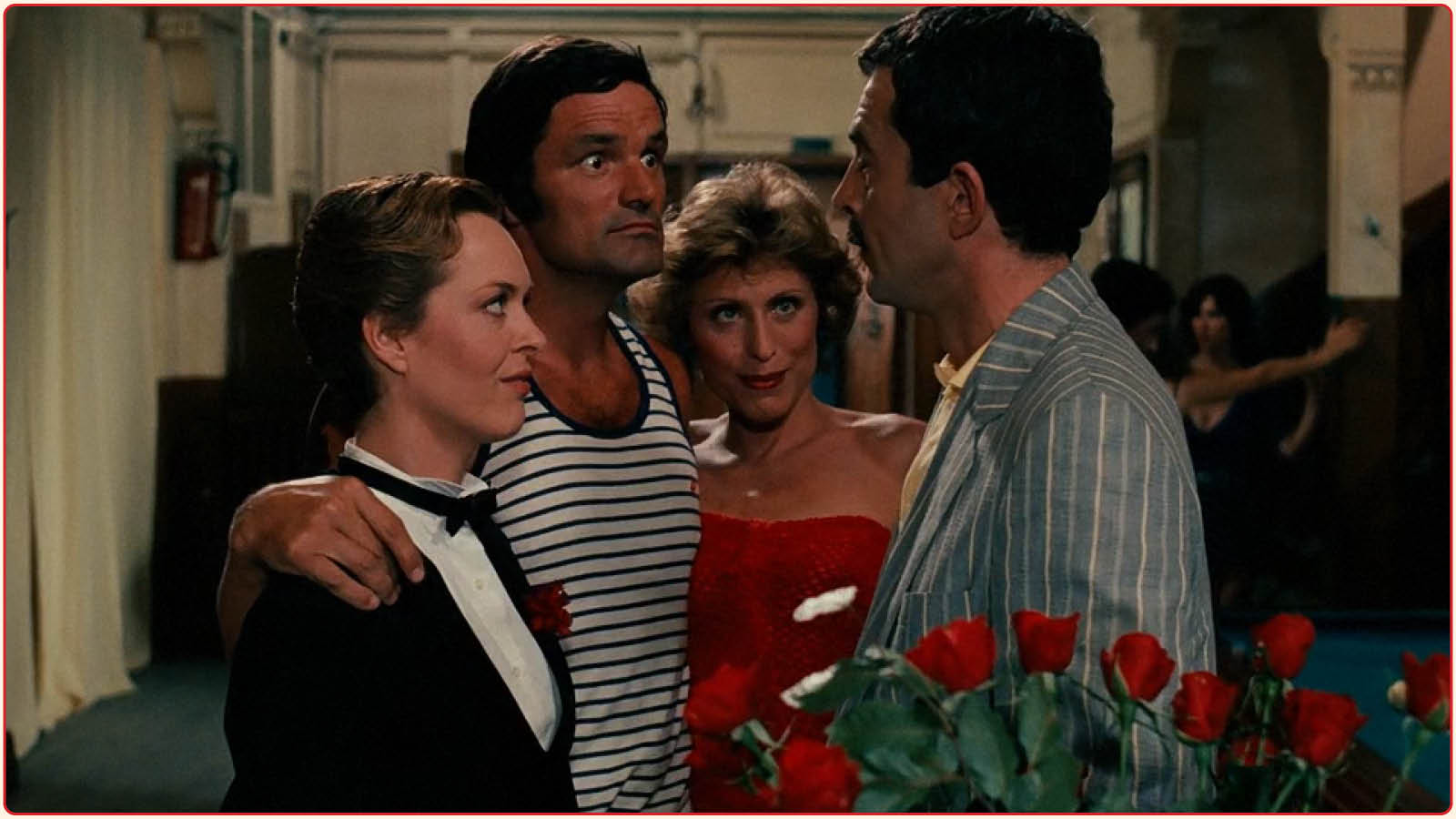

Rosa la Rose is an unabashed product of its influences, collapsing the filmmaker’s personal canonical memories with souvenirs from a broader, shared cultural heritage. The film isn’t a musical, but functions very much the same as one, with a fixed setting (the backstreets of Paris’ Les Halles neighborhood) and a Greek chorus of fellow prostitutes, johns, admirers, and undesirables who cheerfully weigh in on Rosa’s situation when she’s offscreen (typically evincing skepticism at her impossibly charmed life, jealousy at the ease of her business, or simple astonishment at her radiant beauty). At Rosa’s birthday party, a long tracking shot begins as a tableau mimicking The Last Supper, before the camera follows our heroine as she exits her seat and assumes center stage. There, she spins, dances and sings, “God, life would be so simple if I could believe in fantasy!”

Rosa La Rose, Fille Publique (1986)

Given that the walls of her bedroom are plastered with glamor shots of Marlon Brando, Charles Boyer and, again, Darrieux, it’s not a stretch to presume Rosa is referencing the fantasy world of cinema, a worldview that has grown quaint in the subsequent decades and whose limits have since been exposed. But what does this have to do with the oldest profession in the world? Rosa La Rose seeks to reconcile the candy-colored syncopation of Jacques Demy (whose 1964 musical Umbrellas of Cherbourg was gushingly reviewed by Vecchiali in Cahiers, and who would die of AIDS himself in 1990) with the harsh economics of then-president François Mitterrand’s embrace of free-market liberalization and austerity. The film carries the mantle of Demy while engaging the type of subject matter previously verboten (or, by necessity, made wink-wink) in mainstream American or French cinema, a direct refusal of the earlier generation’s trials and errors with neorealism. Vecchiali demonstrates the fine art of paying homage while avoiding facile imitation; he engages comfortable (and, for audiences, comforting) tropes before taking them into less-charted territory. It’s hard to think of an American filmmaker from the same period equally as obsessed with retrofitting and interrogating the tried-and-trues of Golden Era Hollywood pageantry; Zemeckis did something comparable with the only-so-jaundiced postmodern hindsight of Roger Rabbit, while the most spectacular sequences in School Daze (1988) or Malcolm X (1992) suggest Spike Lee had a comparable interest in suffusing all-singing all-dancing spectacle with radical political import.

Rosa’s benevolent pimp Gilbert (Jean Sorel)—also a cinephile, also indebted to fantasy—serves as a voice of reality, reminding her that, at the end of the day, this is a job like any other, and maintaining that she is welcome to walk away from it whenever she chooses. Rather than a creature imprisoned by debt, Rosa is instead presented as a victim of her own certainty, a perfect avatar for the new esprit of individualism over the commons. Rosa La Rose tells a traditional story of innocence lost, but with the added twist that our heroine believes she has seen it all already—a jadedness that falls too easily into naiveté.

Rosa La Rose, Fille Publique (1986)

The film testifies to the eclecticism of Vecchiali’s conception of cinema—where it came from and what it could do—as well as his lightness of touch with actors, and his impeccable eye for choreography. Cheerfully artificial dialogues mean that Basler’s scenes of nonverbal performance are more important than words said aloud, which are inevitably vulgar and inadequate. Everything we see underscores the disconnect between Rosa’s naiveté and the unglamorous reality waiting for her outside this fantasy world.

All told, Rosa La Rose is a staggering high-wire act: an exquisite melodrama about the seedy underbelly of Paris imbued with the kind of flashy punctiliousness we’d typically associate with Golden Age-era filmmakers like Vincente Minelli and Stanley Donen (who were also worshipped by Demy). It’s nothing like Godard’s obstinately Brechtian post-Nouvelle Vague experiments, nor the glistening sentimentality of the cinéma du look that shattered French box office records in the 1980s; Vecchiali’s dedication to carrying so many contradictions in the same breath proves instead the limited use of such broad strokes categories. Embracing such genre elements, every last rip-off or re-paste becomes an opportunity to interrogate the shadows and illusions that have long drawn film lovers in, starting with Vecchiali himself.

Rosa La Rose, Fille Publique (1986)

Share: