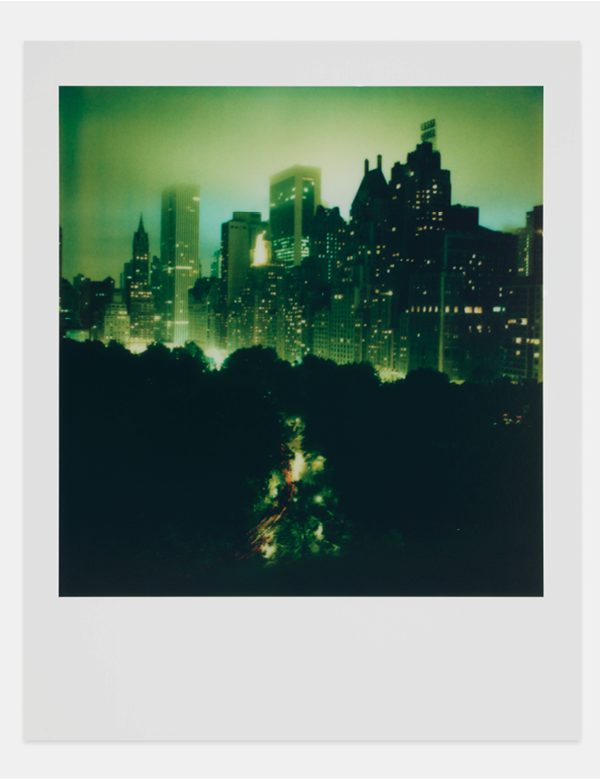

New York City, View From Mayflower Hotel, 1986, Robby Müller

[wpbb post:terms_list taxonomy=’category’ html_list=’no’ separator=’, ‘ linked=’yes’]

[wpbb post:title]

By [wpbb archive:acf type=’text’ name=’byline_author’]

On the Polaroid practice of legendary cinematographer.

Our 18-film series Robby Müller: Remain in Light is currently playing at Metrograph. Unique artist prints are available for purchase from Metrograph Editions.

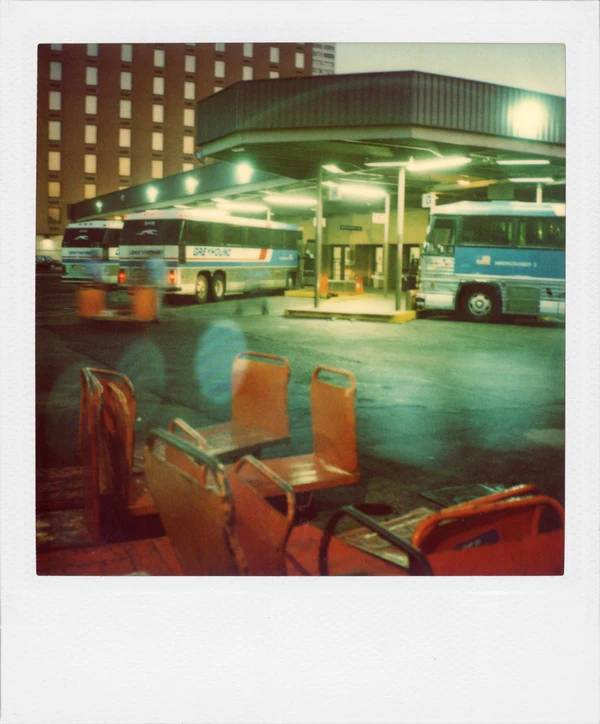

Austin, Texas, 1979, Robby Müller

I often wonder about Gen Z and Y’s deep nostalgia for a time they didn’t exist in-the ’80s and ’90s. To want to experience life before our collective digital isolation, it makes sense.

Trillions of pictures are taken in a day now. That’s more than were made in totality pre-camera phone. I can’t remember where I read or heard this. It sounds true to me.

We’ve become desensitized to the idea of a photograph. Mostly, we see them-or rather, scroll past with a flick of the wrist-on a three-inch screen. Many galleries have pivoted away from exhibiting photographs. The Polaroid, however, has withstood the test of time. An original reference for Instagram. Instant gratification in a tangible form.

Robby Müller (1940-2018) made over 2,000 SX-70 Polaroids throughout his professional career as a cinematographer. He shot some of my favorite films: Jim Jarmusch’s Down by Law (1986), Mystery Train (1989), Dead Man (1995); Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas (1984); and William Friedkin’s To Live And Die in LA (1985).

Robby Müller’s Polaroid New York City, View From Mayflower Hotel, 1986 made me think of Jane Dickson’s cityscape paintings. She has a show currently up at Karma on E 2nd Street.

Hard not to also think of painters like Izzy Barber, Dike Blair, David Hockney, Edward Hopper.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Gus Van Sant, and Nobuyoshi Araki all took Polaroids. I bought a set of two Araki Polaroids from my friend Nick Haymes at his gallery Little Big Man in LA almost 10 years ago. They sit on my desk at home.

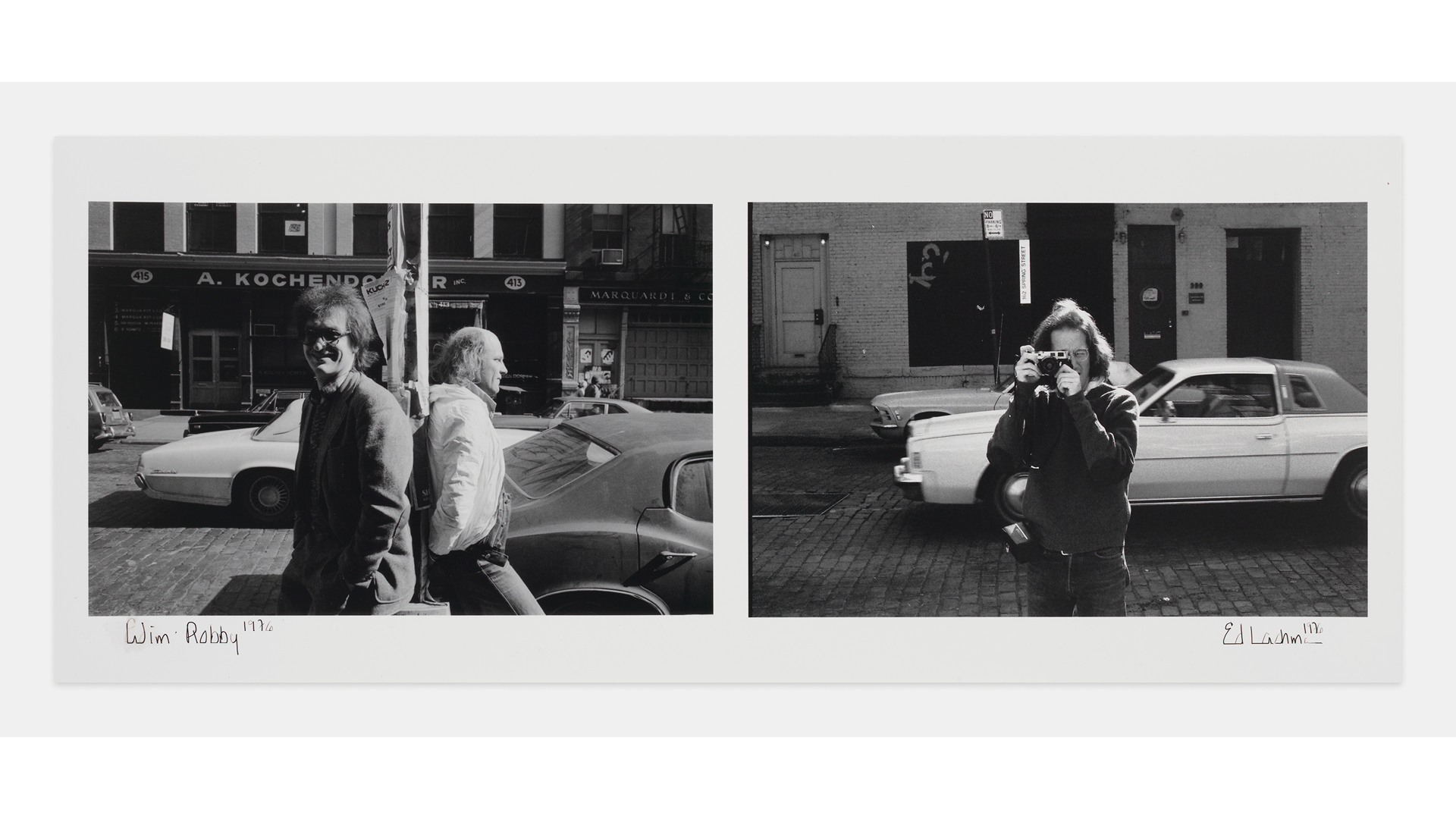

Robby, 1976. Photograph by Ed Lachman.

Müller often worked with avant-garde directors. They saw the world differently. And Robby shot it that way for them. Jarmusch. Wenders. I’ve fallen asleep to Paris, Texas on many occasions. If it’s not streaming, I sometimes will watch a few scenes off YouTube.

His movies look like his Polaroids. The use of natural light. Deep saturated colors. The scene of Nastassja Kinski in a pink sweater flashes through my brain. Polaroid-esque. When Metrograph asked me to write about Müller this is what crossed my mind.

Happy Massee was the first person I called. Happy used Polaroids in his work; even published a book of them, Diary of A Set Designer. He worked with Robby on a commercial in the late ’90s. He described Müller as “understated.” Driven by the chance to work with new people. Not a primadonna. Someone who came to set with excitement.

The use of Polaroids on set is all about transitioning light. Indoor. Outdoor. Streetlights. Windows were used in many of his films. I would suspect he used Polaroids for his trade. To give a sense of how a space might appear onscreen. For continuity. If you had to reset the scene, a Polaroid could give you a sense of consistency. Help pick up exactly where you left off.

I wonder if it started off as a tool. Rather than making art.

Metrograph is selling limited edition prints of New York City, View From Mayflower Hotel, 1986, in a reproduction of the original Polaroid. The picture is illuminating. Comforting. The way a post-rain sky feels at night in the city. I’d like to place it in a thin profile white frame. Surround it with a thick white matte and deep beveled window. Use spacers so the print isn’t pushed up against the glass.

A Polaroid is an object, not just a picture. It has unique characteristics. The glossy surface smoothes out most imperfections. I like the way the matte white framing feels in my fingertips. It’s an edition of one. Like a painting. This print is a remedy for fighting the loneliness epidemic. The one you’ve been reading about, and possibly experiencing. You’ll see it when you get home at night. It’ll look like a small window to the world. It’ll give you an excuse to invite people over to see it too.

Aaron Stern is an artist, curator and author working between the US and Europe. His photographs, books, poetry and curatorial projects have appeared in publications and institutions such as RoseGallery, Magenta Plains, Dashwood Books, Perrotin, Photo Saint Germain, International Center for Photography, Paris Photo, Los Angeles Art Book Fair, Index Art Fair, The Paris Review, Vogue, The New York Times, Dazed & Confused, Interview. Stern is the owner of the curatorial service A Medium Format.

Wim – Robby, 1976. Photographs by Ed Lachman.