Columns

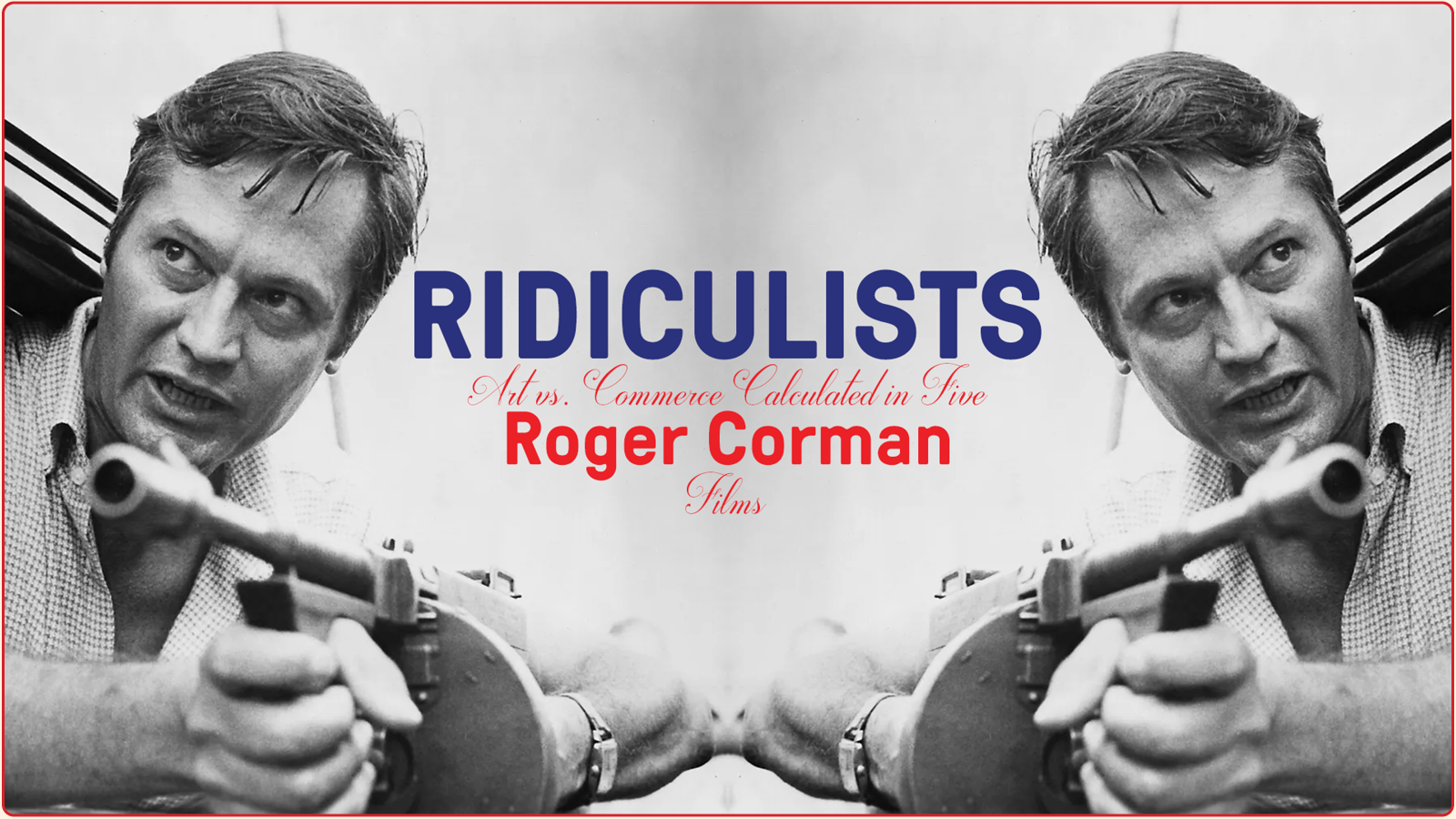

Ridiculists: Art vs. Commerce in Five Roger Corman Films

Film history is a house with many rooms. In Ridiculists, Will Sloan explore some of its nooks and crannies. For the latest entry, a look at the battle between art and commerce in five Roger Corman films.

Share:

The autobiography of the late producer-director Roger Corman was titled How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime. Since Corman was prone to hyperbole, here is a grand statement of our own: no one figure in the history of American cinema better embodied the idea of the artform as a battleground between art and commerce.

Corman was a left-brained thinker in a right-brained industry, a producer-director with one eye on the pocketbook and the other on the zeitgeist, a master of the calculated risk, and a man of refined tastes who often catered to the lowest common denominator. He mentored Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, distributed Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini in the United States, employed more female directors in the 1970s and ’80s than any other Hollywood studio head. He also produced Sharktopus (2010).

Corman often cited his race-relations problem picture The Intruder (1962) as both the pinnacle of his artistic ambitions, and—following its box office failure—a wake-up call to not let matters of art cloud his business sense. For a million different reasons, art and commerce are densely interwoven. But that’s exactly the kind of nuanced thinking we’re going to ignore today. In fact, we have taken an assortment of Roger Corman’s producing and/or directing credits and, following complicated mathematical formulas and a touch of black magic, determined what proportion of art and commerce each contains.

The Wasp Woman (Roger Corman, 1959)

Commerce: Roger Corman was an industrial engineering major who spent less than one week working at US Electric Motors before realizing he had made a mistake. He then entered the movie business because he liked movies and worked his way up from a script reader at Fox to a producer of his own independent productions. He saw that he could probably direct as well as, for example, Wyott Ordung (helmer of 1954’s Monster from the Ocean Floor) and save a little money in the process. So it was hard-headed pragmatism that launched one of the richest and most prolific careers in American film history, and throughout the ’50s Corman directed with the eye of a moneyman. The Wasp Woman is a typical example of this period: a high-concept, ripped-from-the-headlines horror film (inspired by the then-novel craze for cosmetics reputed to slow the aging process), shot for $50,000 in under two weeks, and full of slow, talky scenes that the drive-in audience could neck through.

Art: Corman could have kept his job at Electric Motors, but again, he thought movies would be more fun. Wouldn’t you rather make The Wasp Woman, too?

Commerce: 95%

Art: 5%

Creature from the Haunted Sea (Roger Corman, 1961)

Commerce: In the last week of 1959, Corman took advantage of some standing sets to shoot one more movie before new union rules for residuals took effect. After three days for rehearsal and two for principal photography, production was more or less complete on his The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). As the New Year began, Corman and several of his closest collaborators hopped on a plane to Puerto Rico to take advantage of tax breaks. One film (The Last Woman on Earth, 1960) became two (the Joel Rapp–directed Battle of Blood Island, 1960), and then, finally, a third: Creature from the Haunted Sea. Hey, we’ve got the people and the equipment here anyway—why not? In five shooting days, they cobbled together an unbelievably ramshackle monster comedy and managed to make it an hour long, which finally stumbled into release a year later.

Art: The only type of person who would make movies this way is someone who likes making movies. Picking up on the streak of black comedy running through Corman’s A Bucket of Blood (1959) and Little Shop, Haunted Sea cranks up the wackiness and bothers even less with production value. Lines are flubbed; foliage falls in actors’ faces; dialogue sounds like it was recorded in a tin can; lead actor Anthony Carbone delivers his performance as a cardboard Humphrey Bogart impression, and one supporting character speaks only in animal sounds. Best of all, our heroes are terrorized by a viable contender for Worst Monster in Screen History—a great mound of fabric with two crooked ping-pong-ball eyes. If you’re tuned to its frequency, it’s one of Corman’s most purely enjoyable efforts—a vacation reel from right before Corman broadened his ambitions with the handsome, well-behaved House of Usher (1960).

Commerce: 60%

Art: 40%

Caged Heat (Jonathan Demme, 1974)

Commerce: When Corman founded his production and distribution company New World Pictures in 1970, he began with what he knew worked: naked women. With New World’s second production, the Stephanie Rothman-directed The Student Nurses (1970), the company launched a five-movie cycle of “naughty nurse” adventures that served profitably in the early ’70s. Less than a year later, Jack Hill’s The Big Doll House (1971) inaugurated New World’s participation in the then-popular “women in prison” subgenre.

Art: In several interviews (including this one), Corman recalled, “Jonathan Demme took that assignment and said exactly that: ‘This is gonna be the best one ever made.’” This was the attitude that separated the highest class of Corman’s discoveries from the many others who faded away. An odd tonal mix of camp and violence, Caged Heat is loaded with nudity but pointedly avoids the rape scenes that were a staple of the genre and has the prison guards be women. It also has a socially conscious subplot about lobotomies a year before One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and art-tinged dream sequences that Los Angeles Times critic Kevin Thomas compared favorably to Fellini. With a review like that, Demme was on his way.

Commerce: 75%

Art: 25%

Saint Jack (Peter Bogdanovich, 1979)

Commerce: Many famous filmmakers began their careers as Corman protégés; less repeated are the stories of those who met Corman again on the way back down. Critic-turned-filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich launched himself in Hollywood as an uncredited script-polisher on Corman’s The Wild Angels (1966), working his way up in Corman’s orbit to a first feature, the seminal Targets (1968). While Bogdanovich’s spectacular run in the early 1970s soured into a string of flops, the growing success of New World gave Corman the luxury to dip a toe in the arthouse. Alongside his successful American distribution of films by the European masters, Corman produced a few home-grown prestige pics, including I Never Promised You a Rose Garden (1977), Foxtrot (1979), and Bogdanovich’s project about a charming American pimp in Singapore. Always one to secure his investment, Corman ensured that even his art films still offered a little skin.

Art: It didn’t quite settle Bogdanovich’s wobbly career, but Saint Jack took him out of the Hollywood studio dreamworlds of his post-The Last Picture Show (1971) period into a style that was looser and earthier. Saint Jack benefits from its location filming, use of non-professional actors (including real-life sex workers), relaxed and improvisatory tone, and Ben Gazzara’s amiable but textured performance in the title role.

Commerce: 20%

Art: 80%

Suburbia (Penelope Spheeris, 1983)

Commerce: Low-budget exploitation producers like Corman survive by finding subjects that their better-funded competitors will not touch. One of Corman’s most successful interactions with the surrounding moment came when he correctly observed that Hollywood wasn’t taking the counterculture seriously. With The Wild Angels and The Trip (1967), he met the younger side of the generation gap on their terms, and was richly rewarded. Another generation later, Penelope Spheeris chronicled LA’s punk rock scene in the documentary The Decline of Western Civilization (1981), and for her first narrative feature, convinced Corman that she had found the new counterculture.

Art: Spheeris sets the tone in her opening scene, where a baby is mauled to death by a Rottweiler. Tough and without gloss, Suburbia carries over the ethnographic approach to its world that Spheeris began in her first documentary, built out of stories and observations from the LA punk world and cast with real denizens of the scene. The film’s sympathies are firmly with its suburban outcasts, and is only ever as ingratiating as they are.

Commerce: 100%

Art: 100% (a freak of nature)

Share: