Interview

[wpbb post:title]

By Nicolas Rapold

An interview with director James Vaughan.

Friends and Strangers plays Metrograph In Theatre and At Home from February 25 through March 3.

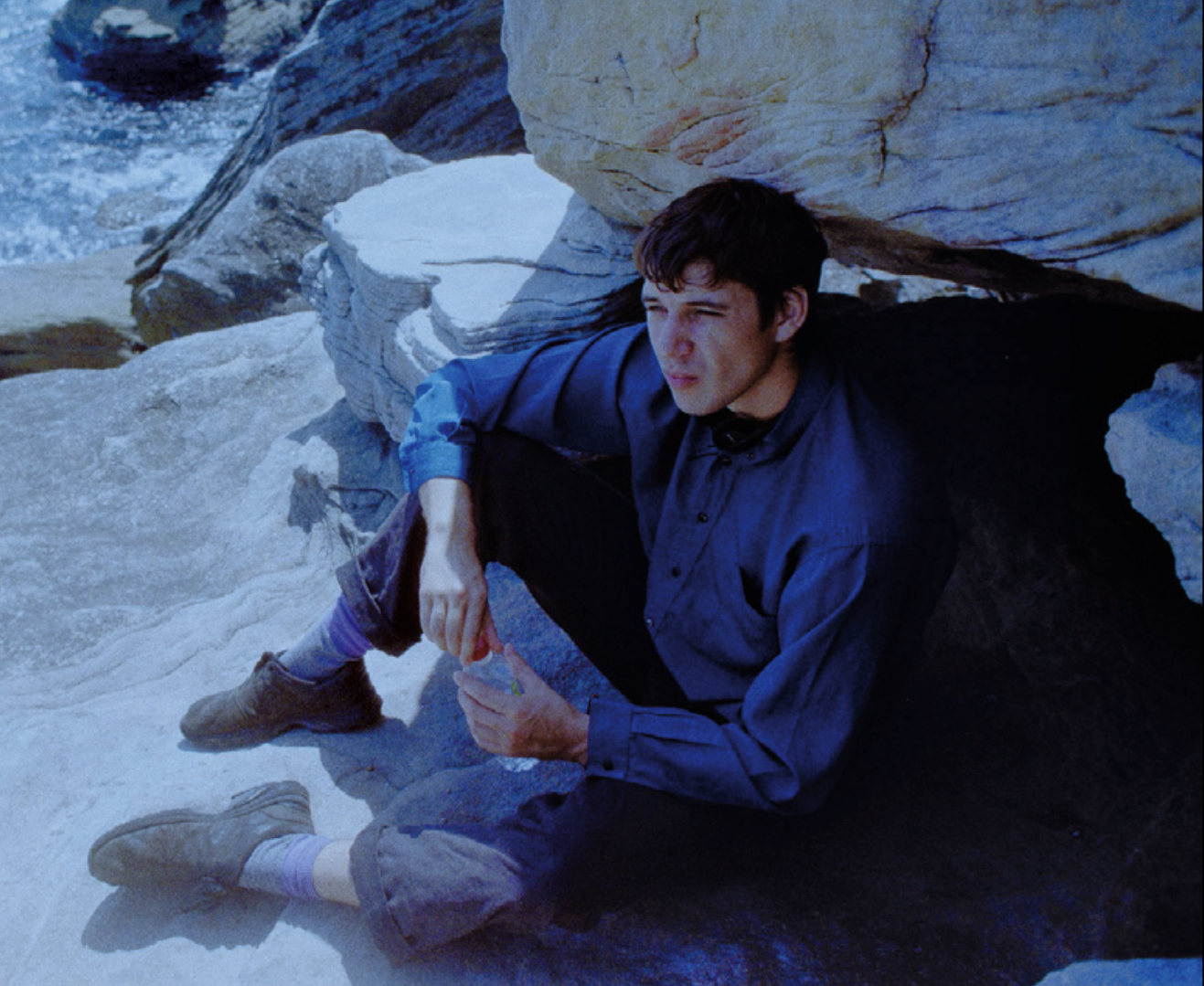

Unassumingly lovely and drolly funny, Friends and Strangers begins by following an aimless young pair of sort-of friends-the strangers come later-down an anonymous stretch of the Australian east coast. Alice (Emma Diaz) has plans for a hike, and Ray (Fergus Wilson) tags along. The ensuing film is easily one of my 10 favorites from the past year, spinning forth a brilliant character study and tragicomic creation in Ray, who’s just trying to get his footing, somehow. Shot with a pictorial beauty uncommon for its sometimes humble scenarios, the film has an unerring sense of the casual rhythms and suspense in day-to-day life and conversation, with an ever so slight panic lurking just beneath the surface.

I’d last spoken with the director, James Vaughan, on my podcast, The Last Thing I Saw, after having the hunch that he might be a great person to chat about movies with. I was so pleased to speak with James again about his terrific debut feature on the occasion of its US release.

I love the way comedy arises naturally out of moments in Friends and Strangers. When you were writing, how did you find that balance without playing things up, or down, really?

For me at least, often things that are funny aren’t funny on the page. Scripts can lean too much on jokes, and you go, “Oh, yeah, that’s a joke. And that’s the punchline.” Maybe that’s why many films often start funny and then lose direction… The films that always interested me more have an ambience you can’t really put your finger on. I guess it’s a combination of the script and the scenarios. It can be comedy generated from the relationship between scenes that maybe wouldn’t normally be put next to each other. It’s more up to you to find incongruities.

I’m trying to write a second film at the moment, and I have found myself doing some of the same things again: starting in quite a dry, deadpan way that doesn’t give much away about the tone of the film, and slowly escalating. It was something I wanted to have in Friends and Strangers-that for the first half, it is not clear whether it is or isn’t a comedy. I like films that shape-shift.

Some of that comes out of Ray’s haplessness. He has this amiable aimlessness, and he’s not yet deeply frustrated with it. So part of the comedy is character-driven. Like when he’s going on the trip with Alice, and it’s hard to tell whether he’s misreading signals or just retreating into inertia. It puts us in the position of trying to get to know him as a person.

There’s an indiscernibility about not just him as a character but also his problems, whether they are even problems or not. I wanted to put people in the position of being like investigators forced to investigate things, where they don’t even know whether they’re worth investigating. We don’t really know what his background is, but we’re trying to figure it out. Do we even care? We don’t really know what his goals are. Does he even have goals? Does he need goals for us to be interested in watching him? These sort of micro-mysteries. For that to work, the scenes in themselves need to be watchable, so I was trying to create almost a synthetic suspense, scene to scene. There’s a sense that something might be coming just around the corner, but you don’t know what that is. I guess people can find that frustrating. It’s like, “Oh, nothing happens, why was I watching that film?” But I like films like that.

There’s a wonderful moment when we’ve leapt forward in time without perhaps immediately realizing that.

Yeah, I felt like the time jump was a sneaky way to have multiple films in one, with it revealing that the first part of the film is a story that someone’s telling. It sets that part of the film in the past, but also in the present; I like the idea of it existing in two times at once, and there being a slightly scrambled sense of time, because the characters themselves are pretty scrambled. There aren’t many things that are marking time in a meaningful way other than these embarrassing incidents, or reflections on long-term relationships that have come to an end. In general, there is a sense of drift in the film.

I wanted that to be there in the structure-but also, as you said, in that dynamic between Alice and Ray. I guess that just felt true to my own experience in Sydney in my twenties, and also to those dating experiences where sometimes they develop into something, other times they just become a story. And it’s a story that sometimes you don’t even tell anyone else… maybe you’ll talk to a friend about it, and it just washes away. So the question of whether Ray misreads or not is partly the difficulty of both him and her not really knowing what they want out of it; there almost is no right and wrong read of the situation because they don’t even know what they’re doing there. Maybe that helps some of the comedy along, just the absurdity of all of that.

I have to pause here and ask: what are all the birds I’m hearing on your end? It’s amazing.

Oh, I’m in the tropical north of Australia. It’s the northernmost capital city, a place called Darwin. Named after Charles Darwin because he was very impressed by this part of the world, the biodiversity. Something like 40 percent of Australia’s bird species are found up in this part of the country. So Kakadu National Park is up here, and at the moment it’s very wet and humid. I couldn’t tell you exactly what these birds are, but there’s just a crazy amount of birds.

It’s this wonderful eruption of wildlife in my ear. I just have pigeons out here, maybe once in a while a red-tailed hawk.

In the movie, the sound design is such a big part of the environment as you’re painting it. The quietude on their hike, for example, or the atonal music that Dave [a wealthy fellow Ray sees about a job] cannot abide.

Sound is the thing that binds, the glue for so much of what you believe in a film. It’s that film school thing: you can get away with a bad picture, but not with bad sound. So when you twist it in moments, it can have quite a profound effect on what feels real. It’s really easy to overdo it, but at times, [I like trying] to move away from a totally naturalistic approach to sound and to do it in a way where it shifts over to something that’s designed, as opposed to something organic laying under an image. I did have fun with the sound designer, Liam Egan, who’s really awesome. [A dog barks in the background.]

I was thinking about a lot of these things even at script stage. Sound can be a sort of a tonal guide rail to help you, but I like the idea of sound as a little bit more abstract and untethered from strictly any emotional or psychological meaning that the filmmakers want us to see in what the characters are experiencing. This isn’t a very psychological film, so if there’s any psychological aspect to it, it’s a more interior quality-as if we’re inside the character’s head perhaps for a short moment and then it becomes more exterior again. It’s more of a description of what we as observers are looking at.

“Through yout twenties, a lot of people are measuring their own commitment to something that they thought they wanted as it gets harder and harder to sustain it. You’ve spent your teenage years and early twenties dreaming about a future that then starts to slip away.”

The second half of the film takes place in Sydney, at locations that aren’t immediately recognizable to outsiders. What can you tell me about Sydney that people not in Australia might not be aware of?

Sydney is the city that a lot of people think about first when they think of Australia, and it was the place where the British first landed, so it was the first colonial outpost. It’s the most populous and I guess the wealthiest in terms of property, retail, property value, GDP, things like that. So Sydney is kind of the city that the other cities often look at resentfully. I’m not saying everyone wishes they lived in Sydney. On the contrary, people kind of hate Sydney, often for good reason, because Sydney can be very entitled. There’s a self-absorption, and also an obsession with commerce too. Sydney has a reputation for not being particularly cultured, even though there’s a lot of money that could pay for culture. We have places like the Opera House and the big-ticket items, but it hasn’t always been the best city for nurturing grassroots artistic communities.

I suppose I grew up in Sydney as a very comfortable, middle-class white person who went to a private school and then to one of the four or five universities that you want to go to, having a pretty sheltered life. But I also had this impulse not necessarily to go in and do the thing that you’re expected to do coming out of that kind of environment, which is become a lawyer or go into business or engineering or property or whatever, the things that earn you money and allow you to buy a nice house somewhere. You can feel a little unmoored in Sydney, and I guess that’s why a lot of creative people end up moving. It’s quite a brutal place if you don’t have money, I guess there’s probably comparisons to New York in that sense.

A lot of people get into their thirties and go, ah, you know, I’m kind of sick of this. I don’t really want to be an artist that much. I just want to have a decent place to live in and maybe start a family. So through your twenties, a lot of people are measuring their own commitment to something that they thought they wanted as it gets harder and harder to sustain it. You’ve spent your teenage years and early twenties dreaming about a future that then starts to slip away. In Sydney, people often reach a crisis point. I was around a bit of that, and that definitely fed into what I was trying to tap into with the film.

Now I’m wondering if there was a Dave in your life who also said to you, “Where’s it all leading?”

Yeah, definitely. All the time. Parents, my parents’ friends, my friends’ parents. It’s a very typical conversation because there is just a kind of befuddlement in Australia-not from everyone but from people who haven’t really come up as part of a creative arts humanities community. There is just total bewilderment, and sometimes I think that goes back to the beginning when the colony began. It was like, “Clearly no one in this end of the world is going to be doing anything that anyone in Paris or London or New York or Berlin is going to take any notice of artistically, so why are you even bothering, mate? Who are you trying to impress? That’s not what we do out here. We work and we try to enjoy the good life.” There’s an incomprehension from people sometimes when you tell them you are doing something that isn’t leading towards a secure income.

That is not meant in a way to upset you, but over time, it can if you yourself have doubts. I remember a Christmas where I had just moved back from Melbourne for a little while. I was in a bit of a mess myself mentally and decided to re-enroll into an arts degree and study ancient Greek. And my auntie was like, “Where’s that leading? What are you doing?” Her intention wasn’t to make me freak out, but it did. It was just the straw that broke me and I had a bit of a cry myself.

Oh no! But… you studied ancient Greek?

I dropped out of the actual language. It was very naive thinking I could take that as a pastime. But I ended up doing maybe a year’s worth of ancient history in a three-year degree. It was while I was working and writing the script.

What did you take away from your studies?

I did a unit on Homeric poetry. So The Iliad, The Odyssey. And I guess there’s an Odyssean element to Ray in some ways. He’s like a pathetic 21st-century Odysseus in his drift from quest to quest, but instead of succeeding as he goes, he’s failing as he goes. I don’t know if that was something I was directly inspired by, but I was looking at that text when I was writing.

And then I did a unit on Herodotus, who is seen as the first historian-the first person to write a historical account based on trying to find out what happened, rather than some religious pretext justifying the origins of things. That [text] is really amazing too because it’s episodic and anecdotal, and leaning into the subjectivities of people’s answers. Just putting down whatever people say, with the attitude that the lies people tell are often more revealing, whether factually true or not. That has really stuck with me.

Another unit I did was pre-Socratic philosophy. The proto-philosophers, the first people in ancient Greece who, I guess, invented the idea of concepts, as bizarre as that sounds. They were coming up with outlandish explanations for the origins of things that were more intuition-based, but also quite profound in some cases. People like Parmenides and Heraclitus. Heraclitus is amazing because his philosophy was expressed in these tiny, poetic fragments that had self-contradictory elements or double meanings, this mise-en-abyme with a bottomless quality, which reverberate between each other. I still pick that book up every now and again.

Heraclitus is the “same river twice” guy, if I remember right.

Yeah, exactly.

That’s an all-time hit. I like that one.

Yeah. That’s his big one.

Talking about origins reminds me of something you wrote that I was just reading. You got into this kind of… concussed shock of the post-colonial state. Namely, that everything seems normal on the surface, people are living their lives, and yet… all these things still happened. It was interesting to learn that colonial history was also on your mind in making this film.

I just find it’s really strange that our country exists at all. I guess everyone around the world grows up and Australia is a real country on the map. People speak English there and they have kangaroos and stuff. But if you take out the fact that it’s a given, it is a really weird country to exist. It’s so far away from other English-speaking countries. North America is the same but it has been around longer and became so dominant that it maybe seems less out of place. There’s Australia’s proximity to Asia and the South Pacific, but there’s so little meaningful engagement with our Asian neighbors. And with the Indigenous population here, too; it’s how superficial the engagement is, and how much lip service we pay to calls to make that engagement more meaningful.

Australia’s history is so bizarre. The national holiday is a military service day, like in a lot of countries, and the founding day of the nation. But then you look a little closer, and both of those are really strange days to be defining nationhood around. The founding day is the day that Captain Phillip-he’s one of the statues in the film-arrived in Sydney and planted the British flag. It’s not the day we became an actual nation but the day the dispossession began for Indigenous people, and the [British] illegally decided on behalf of the Queen that this whole place was theirs. And the other day is Anzac Day, a celebration of when our military was lured over to Turkey in WWI to fight in a sort of proxy distraction war, while the Western Front was going on. We were utterly vanquished, and retreated with our tails between our legs, and that’s somehow twisted to become this glorious moment where our identity as a nation was forged, when we lost an imperial war we had no real right to be fighting.

The fact that they’re the best days that we’ve been able to come up with to create a certain idea about the country points to some deeper problem in terms of who we actually think we are. And there’s a delusion about Australia that is going to hit a hard wall at some point in this century, as ominous as that sounds, where we have to yet face up to reality and our past.

It’s interesting that some of the most famous cinematic imagery to come out of Australia is postapocalyptic.

Yeah, and horror stuff too. A lot of our hit films from the last few decades are horror films. The horror isn’t necessarily about these issues, but the fact that there’s an attraction to it that no one can really explain points to something uncomfortable in our conscience, or in our hearts, about what we’re doing here, and a fear maybe that one day we’ll be exposed for it or uncovered. You know, that things on the surface aren’t what they seem. So I guess this was an attempt to look at some of those things without necessarily going for classic horror tropes. But in some ways, it is a bit of a horror film.

There is a sense later on in Friends and Strangers that something sinister might happen. That’s kind of the auditory joke of the atonal music we hear at Dave’s house.

Yeah, it was a naughty way of having a horror feeling but not having to actually have a horror scenario.

What’s the art that covers the walls? Was it someone’s house or was it collected for the film?

That’s a house that was basically as you see it in a film with a few tiny changes. It belongs to an art consultant who is buying and selling and moving a lot of paintings all the time. So as a storage solution, she has her walls covered in paintings. I did actually visit that house years before and I’d written the script for that house. I assumed I wouldn’t be able to use it. But then searching for something similar in pre-production, it dawned on me how attached I was to that place. The owners are really supportive. It was amazing because if that part of the film hadn’t been right, I don’t know if it would have worked.

It’s such a fascinating counterpoint to the film’s exteriors, this riot of material on the walls.

People who know the commercial art environment in Australia will recognize these artists. They’re big names. I couldn’t tell you which ones are which. But they’re works that sell for a lot of money, so it gives that whole set an extra kind of presence.

Let’s talk about your planning out the look of the film. DP Dimitri Zaunders’s cinematography is magnificent in its beauty.

Dimitri’s influence is in every moment of the film. He was one of the first people involved and we spent so much time together in preproduction. For every line of a script, we spent a long time in every location. Knowing that it would be all shot basically-there’s a couple of exceptions-on a tripod and without any camera movement meant we could plan in detail where the camera would be pointing, and at what time of day. And time of day was really important to Dimitri. He really wanted to have the whole film backlit, [which plays] a big part in giving the film a three-dimensional depth. Even though the frames are often static, there’s a life that breathes through them, which is this three-quarter backlit approach Dimitri had. But it’s not just like a formula-his sensitivity for light is just amazing, and choices around the texture of the image too, the lenses, and a certain softness.

I have to mention the colorist, Yanni Kronenberg. Their collaboration was almost an extension of the actual shooting process… I knew I wanted to have the film in these kind of locked-off compositions with very long takes, and Dmitri was really excited by that, the detail he could dive into in terms of planning light in those frames.

The film is shot in places that maybe you wouldn’t ordinarily see on screen, like when they’re hanging out by a roadway at the beginning. What neighborhoods are these?

At the beginning they’re in Ultimo, which is near where I used to work in Sydney. I was walking around there a lot, so when I was writing the script I was thinking about that place, even though in the script it’s in Brisbane. I ended up faking it there because [that part of Sydney] has some similar qualities to Brisbane, like these overpass car ramps.

Nielsen Park is the location for most of the beach stuff. That’s my favorite harbor beach. There’s the heritage house that features in the film, and there’s this strange kind of European quality. Obviously, the whole of Sydney is like that, but maybe this is in the harbor you don’t have the surf beaches that instantly scream Australia. I liked that this is a bit more gentle and maybe a side people don’t see or think of so much.

Thinking about casting, how did you find Fergus Wilson as Ray?

Fergus was just good luck, really. He was a friend of a friend who I bumped into at a lecture at Sydney Uni, years and years ago. He was shooting it-a videography job to capture the lecture. He knew I was writing a script and said he’d like to help out. When that time came around, I needed someone to shoot the auditions and I remembered Fergus had that camera, a small DSLR, and he’d said he was keen. At this point, I’d been asking just everyone for favors and was trying not to cold-call people. He was there in the audition room just shooting the audition tapes with me for days.

For the Ray character, no one had even been close. We were starting to panic a little because this is like two, three weeks from preps and shooting. We still didn’t have half the cast, and that was a whole other saga because we had a casting agent that kind of disappeared. But at the end of one of our last days, we had some extra time, and so we said, “Fergus, why don’t you give it a go?” As soon as he started, it was like, “Why didn’t I see this? This person is perfect!” Then it was a process of convincing Fergus it was worth moving some other big things around in his life to make time for the shooting.

I was trying to put a finger on how he seems to differ from the others. This might sound weird but he seems more… British.

Yeah, he is-he grew up in the UK, or spent some time over there, and has family in the UK. Weirdly I didn’t really notice until halfway through the shooting. I was like, wait a minute, you sound British! I thought he’d started doing it. I kind of lost my temper at him a couple of times. I was like, “Fergus, what’s this British thing you started doing? You’ve got to drop it.” I think I was just completely losing my mind with stress at this point. It was absurd, I was asking him to change the way he’d always been speaking.

Also the obliqueness of his delivery and rhythm. He seems like he’s on another clock.

Yeah, his befuddlement is very organic.

How did you cast Alice? She’s so key to the journey of the movie’s first half.

Emma Diaz, who plays Alice, was one of the people we saw as part of the casting process. She’s an actor, and in one of these last-minute desperate Facebook call-outs she put up her hand and came through. Once she had done the audition, it was like, okay, that’s done. She’s amazing. And it wasn’t just her performance but her composure in a pretty weird environment out at this caravan park, with a whole bunch of people in front of and behind the camera who were doing it for the first time.

The caravan park is one of many examples of beautiful attention to color. The shot looking out from their tent could be framed, with its orange and red hues.

Yeah, the colors were something that we worked out with the production designer Milena Stojanovska. For the color scheme for the campground, knowing there’d be a lot of green particularly, we decided to go for a primary color for the objects that were going to be key, the blue-red-yellow palette for as many of the objects as we could: the yellow umbrella, the red tent, things like that. It was color theory stuff that I don’t really understand. But it helps those primary colors really stand out against the green. I love that, too.

Last summer we talked about your experiences watching silent cinema on The Last Thing I Saw. Now I’m curious about what you are watching these days.

I had wanted to move through the decades, in similar ways to what I was talking about with ancient Greece. I think that was part of going back to silent film, with the sense of being confused about everything, and so starting at the start might help figure some things out. But I’ve just gone back to watching films from the last 20 to 30 years… Last night I re-watched Teorema. God, it’s a good movie.

So good, and when I saw it, I started seeing its influences in so many movies.

Yeah, but also what I love so much about Pasolini is that there’s some ineffable thing that is Pasolini. It’s hard to even pinpoint what that is because it’s so elusive. It’s in these micro moments -a shake of the camera, or an odd cut, or an odd look down a lens-that is very hard to systematize or reduce. I don’t really know how to describe it, but it’s just like a magical Pasolini essence that my favorite films of his have an overabundance of. The Gospel According to St. Matthew is one. And I just love Teorema so much. It’s so insane, but he presents everything as if it’s the only way-the only state of things that could possibly exist.

Nicolas Rapold is a writer and editor. He hosts the podcast The Last Thing I Saw.