Essay

Camera! Rosé! Action!

Translated by Ted Fendt

A chapter from the French New Wave filmmaker’s memoirs, detailing the making of his 1971 “Bouillabaisse Western” A Girl is a Gun.

A Girl is a Gun plays at Metrograph from Friday, December 19.

Share:

Luc Moullet’s Mémoires d’une savonette indocile (“Memoirs of an unruly piece of soap”) was published in France by Capricci in 2021. This chapter, “Camera! Rosé! Action!,” detailing the making of A Girl is a Gun, has been translated into English for the first time for the Metrograph Journal by Ted Fendt.

I HAD WANTED TO MAKE a Billy le Kid for a long time. In 1957, when I was 20 years old and I learned that Arthur Penn’s The Left Handed Gun (1958) was in fact a life of Billy, I was already furious about being beaten to the punch. Billy’s story was not so exciting to me. Billy was just a small-time crook, a miserable little guy most faithfully portrayed by Stan Dragoti in his Dirty Little Billy (1972). The exact opposite of the legend. What I liked was the sound of the name, and the idea of shooting a Western.

*

I admired the great Americans, especially Hawks, who was able to make the best Western (1959’s Rio Bravo), the best gangster film (1932’s Scarface), the best comedy (1938’s Bringing Up Baby), the best war film (1938’s The Dawn Patrol), the best science fiction film (1951’s The Thing), the best films about aviation (1939’s Only Angels Have Wings) and cars (1932’s The Crowd Roars). In my very pretentious innocence, I thought this was the method to follow: comedies (1966’s Brigitte et Brigette), an adventure film (1967’s The Smugglers), a Western (A Girl is a Gun), and a crime film (1998’s …Au champ d’honneur and my 1990 project Remèdes désespérés), to which I would add an erotic film (1976’s Anatomy of a Relationship), a social documentary (1978’s Origins of a Meal), and a literary adaptation (1996’s Le Fantôme de Longstaff). Almost as varied as Hawks. However, I’ll never make a science fiction film (too expensive: my Vortex found no takers) or a musical comedy (I can’t tell the difference between F-sharp and B-flat). Finally, of everyone at the Cahiers, I’m the only one, along with Godard, to have taken on the Western.

*

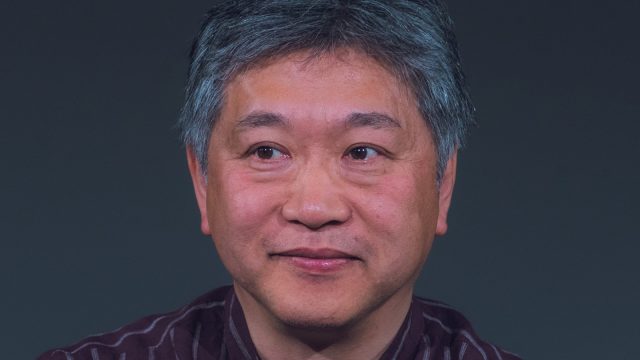

I took another look at the idea for Billy when Jean-Pierre Léaud, who was a fan, asked me to make a film with him. The producer André Michelin wanted to shoot with Jean-Pierre in Hong Kong. I wrote a project for him with Léaud as a Chinese man, recalling Stroheim in blackface at the beginning of Bernard-Deschamps’s remarkable Tempête (1940) and Barthelmess as the “Yellow Man” in Broken Blossoms (1919). That went nowhere. So I started working on Billy. The advantage was that I was going totally against type, a bit like Schwarzenegger as a philosophy professor. Léaud, until then mainly present in the bedrooms and on the streets of Paris, and who could not drive or ride a horse, became a bandit in Arizona.

Léaud was easy. He didn’t read the script. He went through the schedule shot by shot just before shooting so reason would not kill instinct. He asked me: “Luc, what happened before? What happens next?” And once I called “camera,” he would shout: “Rosé!” The assistant handed him the liter of cheap wine. Only afterward could I say: “Action.”

*

The Western: no need to go very far; Haute-Provence was the ideal shooting location. I had already scouted everything in my head. To purists, I would say that the Rocky Mountains are in fact a copy of the Southern Prealps since the former date from the start of the Tertiary era and the latter from the late Mesozoic. Five million years before. Monument Valley is a remake of the Roquesaltes near Saint-Véran along the Causses.

The Western: therefore the desert. No need for sets or houses. In Billy, we only see two: my family residence above the Sisteron, built in 1661, and that of the Roux in Mariaud, which did not clash with 1880 America (in 1970, there were not yet power lines in Mariaud). No need for a lot of actors: I had in mind the example of a beautiful classic Western, Anthony Mann’s The Naked Spur, featuring only five actors—James Stewart, Janet Leigh, Robert Ryan, Ralph Meeker, Millard Mitchell—plus a dozen Indians in one brief sequence. I had two lead actors, a few secondary roles and the occasional extra.

A Girl Is a Gun (1971)

As with The Smugglers, the assistants were chosen because they had a car and for their appearance, depending on the small role they could play: less people to accommodate, pay, lug around. Sometimes this came back to haunt me: my props assistant, wonderful on Brigitte et Brigitte, became a total junkie and was no longer dependable. I should have replaced him during the shoot. But I couldn’t: he still had to act in three scenes. In Paris, I had already had to ask him to slip me the key to the production van through the cell bars of the prison where he was locked up, wrongly, for abducting a minor on the eve of the shoot…

*

In 1970, the Western was the genre favored by buyers around the world. I joined Unifrance to export my productions better, and all of my correspondents demanded adventure films (hence The Smugglers) and Westerns. When the film was ready in early 1971, the trend was already a bit outdated. Production delays often exceeded the duration of good scams. As a result, Origins of a Meal, a militant social problem film, is more 1968 than 1978, the year it was completed.

*

I started Une aventure de Billy le Kid on June 15, 1970, after the tidal wave of 1968. Before, my collaborators had always been very kind, and obedient. May ’68 encouraged revolt: my actress had the same number of shooting days as Léaud, but earned four times as less. She demanded equal pay. After nine shooting days, my assistants, who were collecting a third of the union rate, demanded a percentage of the film’s revenue. They went on strike because they found a 40-minute climb on foot too dangerous, and at the end of it they didn’t receive lunch. My assistant carrying the food had misunderstood my verbal instructions the night before. It’s the only time in my life where the lack of call sheets was felt. And Léaud had a double because he could not handle being placed on a rocky platform, out of danger but above a chasm.

As in the past, I left everyone free to eat what they wanted at the hotel, which had not led to any downward spirals. But on Billy, some folks, considering themselves underpaid, made up for it on the dishes and fine wines. A druggie squatter slipped into the crew. My assistant cameraman refused to load the film magazines before the start of each shooting day, considering that unpaid overtime. When we continued shooting after the break, my actress arrived 24 hours late. Dope made the assistants forgetful. In short, there was friction. Up until then, I had felt at ease and in a friendly relationship with everyone, not having a foreman’s soul. But I was sometimes overwhelmed by the discontent and casualness. I was too easygoing.

*

I started with what was a huge budget for me: an advance of 150,000 francs from the CNC (National Film Center), much more than the total cost of my first two films, and I had no worries. But we soon went over budget. The finished film wound up costing 230,000 francs (or three studio apartments in Paris). In fact, I never knew the exact cost: there were too many bills, and it would have served me no purpose to do the math. The difference between the two figures was not made up for, even less so given that there was a problem with the German distributor who offered me a definitive deal of 30,000 francs. But Léaud, used to the huge revenues of Truffaut’s films, told me it was a paltry sum. So I was reluctant to sign the contract. So much so that at the end of shooting, the German wanted to see an assembly cut and pulled his money out after the screening. Leaving me with 80,000 francs of debt.

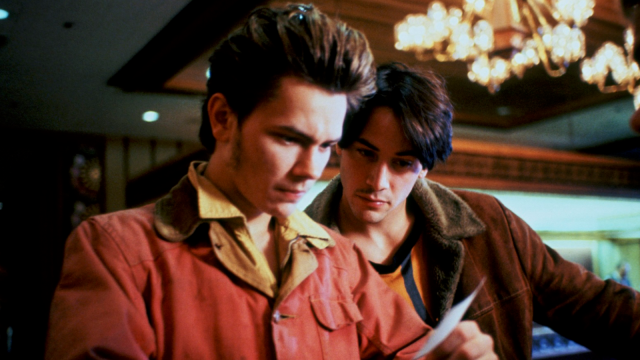

A Girl Is a Gun (1971)

The debt was also created by delays in shooting: my crew consisted mainly of citizens unaccustomed to the open air and sun. To gain a little energy, Léaud, after taking amphetamines (I went with him to the doc so he would have an easier time getting a prescription), did 12 shots in two hours—a record—then collapsed. My actress Marie-Christine Questerbert, annoyed that Léaud was allowed to have uppers but she was not, asked him for some. So one fine morning in Mariaud, my favorite village, I had her do a risk-free shot in which she had to walk from the door of a house to a large rock overlooking the cliff (from which she was supposed to jump, out of frame, of course). In the second take, she kept walking, moved by my directions (“You’re a zombie,” I shouted: the danger of directing actors on post-synched films) and very likely also by the uppers—still, the theories about this subject differ. And she was bothered by the fact that three or four men were attracted to her. She wound up 50 meters below covered in blood. On the way down to find her, I didn’t think she would be alive. She came out of it miraculously, having rolled flexibly into a ball, without tensing and without fear: “It was very nice, I didn’t feel a thing.” I had a big surprise: Marie-Christine’s right thigh, so sculptural, so beautiful, was open and full of cellulite. The fat saved her life.

I recognized the ambiguity of fat years later. Its near absence allowed the surgeon removing my spleen, eaten up by an Algerian microbe after a retrospective in Algeria, to make an invisible, vertical scar in the middle of my stomach, hidden by my hair. But without fat, it’s hard for me to stand the cold. On the sidewalk in Ayacucho (Peru), in the shadow of houses and 20 below zero, I had to run to avoid the cold and diarrhea…

*

Let’s return to our Alpine sheep. The rest of the shoot was delayed by a month. Second trip, second camera rental, change of camera operators, Jean Gonnet being booked on a film with Téchiné in Portugal. Since the two cameramen had not been in touch, the one shot in 1.66 and the other in 1.75. In 50 years, nobody has noticed except for a friend who was a cameraman. Gun experts noticed that the sounds of the 24 gunshots in the film came from different weapons than those on screen.

This second part was more tranquil, more professional. Just small problems: on the limestone of the Platé Desert, the horse refused to budge above the narrow chasm of a steep sinkhole. I had the same problem myself in Peru below the Nevado Huascarán, my mule getting stuck right before a bridge through the surface of which there were occasional glimpses of the river below.

I forgot to mention that there had already been dangerous signs. Marie-Christine climbed up to hide the treasure in a cave halfway up the face of a cliff of red, hard sand, 20 meters above the camera. I went to up to give her directions about what gestures to make in the location. We were momentarily out of the crew’s sight and Marie-Christine’s boyfriend, there to make a (soon abandoned) behind-the-scenes documentary, wrongly believed we had gone up there to share a kiss. In protest, he planted himself in the middle of the cliff face, above the void and in the middle of our frame. Oblivously, he braved the danger; none of us had the suicidal courage to remove him. He came down an hour later.

That night, high, he got drunk and threw up in bed, which my actress immediately left for the one I was sharing with my girlfriend. I found myself in bed between two beauties, but I had to be as still as a stone, of course. My star told me that if I didn’t clean their bed, we would be kicked out of the hotel. It’s hard to be a filmmaker, especially since I suffer from a delicate allergy to vomit. Four days later at the Hôtel du Verdon in Castellane, my star, who couldn’t hold her liquor, threw a glass at the head of the waiter with a sinister face. Ordered to beat it from the hotel at 9pm, we staged an occupation, but had to change digs at dawn. There were no further incidents in Castellane. Lucky for us, since there wasn’t a third hotel available.

A Girl Is a Gun (1971)

Seven days later, in Sisteron, not to be outdone by Marie-Christine who, a little drunk, had crushed one of the hotel’s nativity figures in the palm of her hand, Léaud, disappointed to find a shriveled steak on his plate, decided to attack the lady of the house in the rear end with a bottle of beer, helped by one of the assistants. He had asked me permission to do so. I had replied with an acquiescent smile, not thinking for a second that he was really going to do it. Plus, I didn’t want to play the bogeyman. They didn’t go all the way in their attempt, but we all wound up at the police station until midnight. And we had to change hotels again.

*

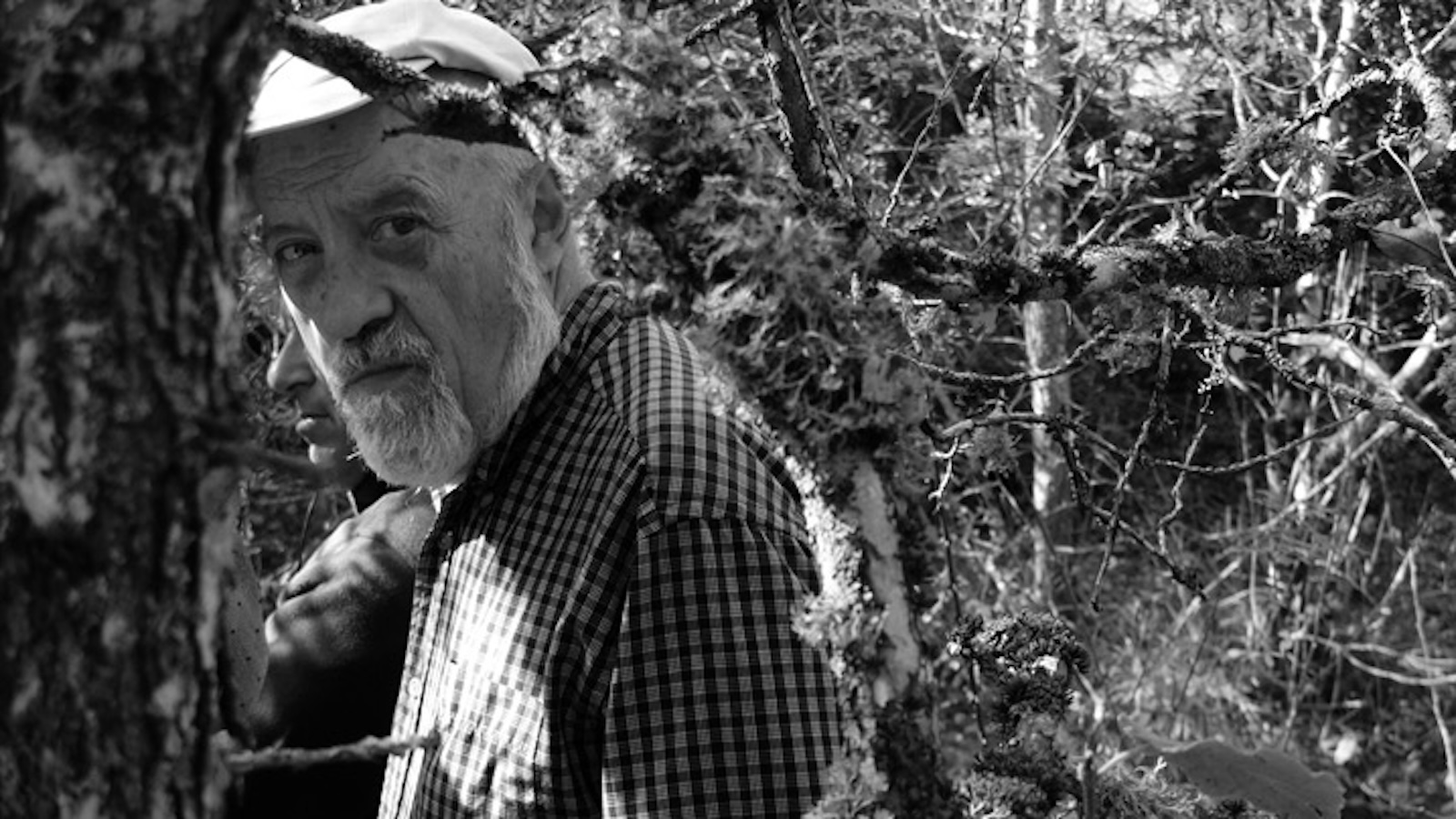

At one point in Billy, we see a dead body played by my dad. Some have deduced from this that I wanted my father to die, which I think is going too far, since there had always been a kind of complicity between my father and I. He died five years later, shocked about receiving a fine, and he embodied—unlike mom, more “normal”—a taste for jokes, which a child always appreciates. But his fanciful side could also turn against me. It’s due to this experience that, consequently, I always tried avoiding conflicts with my family, and also on my sets. This has led to me being rather well regarded by my crews, except for some actors who nag me in order to get a fight going and who are frustrated when I keep my mouth shut. Not necessarily the best tactic.

Dad was always on my back. Extremely paranoid, he kind of reminded me of the hero in Él (1953). He followed me when I would go to the movies alone at night when I was 18. Do you understand? A doting father. It scared me: was I going to become a daddy’s boy? I defended myself, sometimes stopping him with a bit of masochism from helping me (his paranoia drove him forward against all odds: thanks to him, for The Smugglers, I had an advance from the French distributor making up 21% of the budget). And ultimately, he was the one who became a daddy’s boy. He took pride in front of his coalmen clients about having a filmmaker son, which increased his sales [Moullet’s father sold the black work clothes worn by men who sold coal for heating –Trans. note]. He was always unusual. He never had a store or employees, and was never listed in the business register. Never in his life did he pay taxes except in his final years, when I forced his hand a little (he bawled me out) and made him get a social security number when he was 50. As soon as the boxes of black clothes arrived at his place, he had them brought up to his apartment on the sixth floor by a fireman neighbor whom he tipped, then he separated them based on the delivery route and, for the first 40 years, delivered everything by motorcycle. I must have taken some inspiration from his system.

*

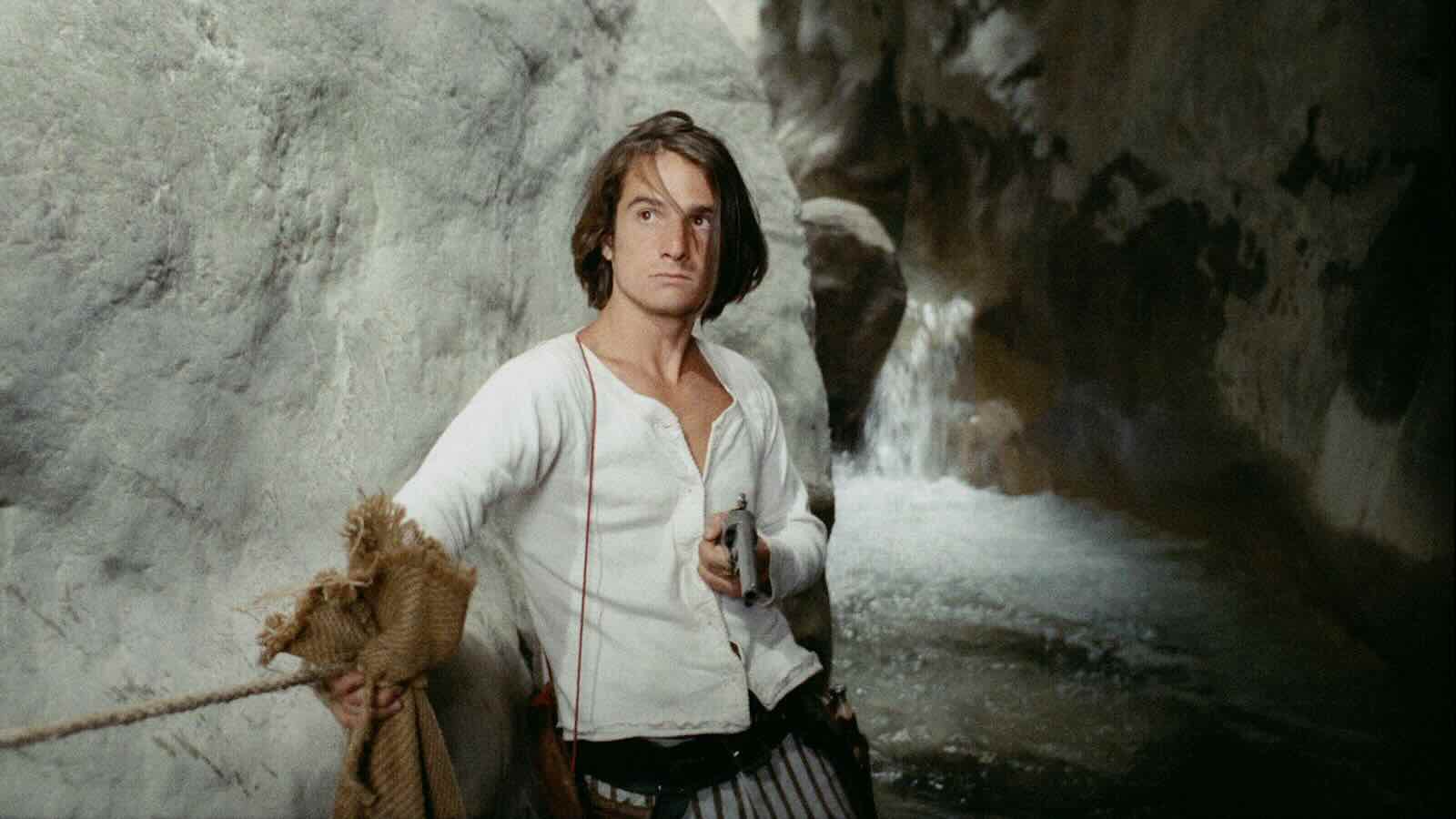

Coming back to Billy: it was Marie-Christine’s first film role. Two months prior to the shoot, she would never have imagined becoming an actress. Suffice it to say, she was perfectly relaxed, a considerable trait. Her acting experience was a slight digression in her path toward being a director, which began with her beautiful documentary Buy Me, Sell Me (1969).

She was successively a philosophy graduate, director, actress, journalist, film writer, and teacher. This is all understandable when these activities are more or less simultaneous, but infinitely less when they succeed one another, leaving the impression of failure or instability, confirmed by the multiplicity of names in the credits (Rachel Kesterber, Marie-Christine Questerbert, Christine Hébert, and she wanted to use Fleur de Lotus as a pseudonym). In a way, this is the drama of women who are too beautiful—the same could be said about Iliana Lolic—who don’t have any material worries and who let themselves go a bit, lazing about, whereas either as a director or as an actress, it is always necessary to put the pressure on. Marie-Christine’s indifference (it’s only a movie after all, why worry?) played more than one trick on her in the preparation of her shoots.

She has a very feminine side, but, at the same time, it was interesting to make her act with certain, almost masculine, characteristics, with her physical force: here, she has an advantage over Léaud. In the old days, this male/female dialectic, the masculine appearance adding to the femininity, contributed to the success of Marlene Dietrich, Jane Russell, Louise Brooks, and Jean Seberg. A voluptuous woman from Brittany, she stunned me for the way in which, a modern Valkyrie, she leaped and bound around the streams.

A Girl Is a Gun (1971)

Unlike many seasoned artists, she handles slightly exaggerated make-up very well, placing her within a poetic lens based on theater and the imaginary. I also adored her spontaneity in Anatomy of a Relationship when she improvised during a three-minute shot, telling the story of her abortion.

*

Unfortunately, Billy was a contraband Western with my brother’s pop music and deliriums rather foreign to the genre. The title, Une aventure de Billy le Kid—a reference to C.B. DeMille’s Une aventure de Buffalo Bill (The Plainsman)—can be read as a bit of wordplay: the adventure is romantic. The film scared everyone in France. It was too unusual. After striking the answer print, I spent over two years finding a distributor, Lusofrance, who couldn’t manage to find a theater in Paris that would agree to open the film. What saved me was that abroad, the title and the genre clicked… In that happy era when video cassettes and DVDs did not yet exist, buyers made judgements based on external elements: the charming trailer and the press kit I had concocted. The Third World took the bait. What a blast I had going to a cafe on the Champs Élysées to meet a possible Mexican client, Oscar Lopez Trincado. He simply asked me: “¿Hay mucho acción en esta película?” “Sí,” was my reply. At the time, that was just about all the Spanish I knew. And he signed a check. Africa followed, as well as Venezuela, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and the Philippines, where I had the pleasure of selling the film twice, the first distributor having been ruined by a typhoon and unable to settle the final accounts. These were small transfers—$800, $1,000—but after three years I had almost resolved the situation. Three years of work and intense international correspondences with the fine basic rule: never show the film. One day, I even sent a friend, a very pretty girl, to meet an African distributor who was supposed to attend my private screening. He dishonestly pretended to have gone and to have enjoyed Billy, which he confirmed by buying it immediately, thereby soothing the remorse related to his absence.

When a stone falls in a lake, rings form on the water, close at first, then further apart. I did the exact opposite: more and more concentrated circles from Indonesia toward Europe. The film arrived in Turkey, then Italy: the Italians bought Billy sight unseen based on the title, like everybody, but after paying, they sent back the materials, judging it impossible to distribute even on TV. From then on, that client decided to see each film before signing any contract. Darma Putra Yaya, my distributor in Jakarta, horrified by such an atypical Western, had it banned by the local censors—allowing him to demand I pay him back the royalties—and he returned the prints. He’d forgotten that my contract had a clause, in fine print, requiring him to appeal the decision to ban the film within two months—thanks to my little investigation into the legislation of Indonesian censorship, I kept the money, and the prints. In vain, I tried to resell them by traveling to Peru. I tried my luck in Thailand too, where there were good clients who gladly made blind purchases, like Prasert Srisomsup, Sonchai Kitiparaporn and even Wendai Artavedvoravudi.

*

Naturally, the critics were divided. After the Hyères Film Festival, Albert Cervoni found it, “Luc Moullet’s best film. Léaud pulls off a dynamite creation in what is more than just a simple Western parody in splendid natural settings” (L’Humanité, June 5, 1971). Émile Breton noted: “Beyond the brilliant exercise in writing, beyond parody, the film culminates in a tremulous discovery of love in the audience and a howling confession from a scalped and crippled Jean-Pierre Léaud” (Le Petit Varois, April 27, 1971). On the other hand, for Mireille Amiel (Cinéma 71, June 1971): “Of the out-of-competition films, undoubtedly the worst was Une aventure de Billy le Kid by Luc Moullet. Everybody can botch a film. My first concern is that he botches them all.”

*

In fact, Billy is very uneven, marked by the on-set disturbances and difficulties, but with stand-out moments: the two, highly unusual songs; the nearly speechless, very lyrical final 20 minutes; the route taken by Léaud, a fine sleuth who seems to sense a path over several meters in the desert and continues to follow it among the immensity of the loose stones of Mount Ventoux, suddenly revealed thanks to a short pan. And then Léaud who blushes during a long shot where he tries to strangle himself with the rope of his failed hanging, the unexpected arrival of dialogue in the (fake) Indian language, Léaud’s various explosions, especially the moment when, famished, he delights in eating an emaciated shrub as if it were a succulent mutton kebab. What I did not like was Marie-Christine’s “off-key” note when she sings a drawling “yooo,” or the exaggerated presence of a psychological debate in a work of pure fantasy. A film based on strong moments rather than a harmonious work, and playing with duration. As John Ford said, what remains of a film is not the story or even the whole film, but a few unforgettable moments.

A Girl Is a Gun (1971)

What was most shocking was the mixture of Western, pure comedy, parody, and emotions related to the characters’ amorous feelings or the intensity of the pop music. A mixture of genres stemming from Elizabethan theater and the picaresque English novel.

One can certainly hold its abundance of references against Billy: 1946’s Duel in the Sun, of course, Nick Ray’s 1955 Run for Cover (the discovery of the streams), Vidor’s 1949 The Fountainhead (the low-angle shot of Marie-Christine above the pit), Fuller’s 1957 Run of the Arrow (the wagon wheel spinning in the air at the beginning), Hughes’s 1943 The Outlaw (women associated with animals). There seems to be a quotation from Sirk’s Taza, Son of Cochise (1954), a dud I thought I’d forgotten. But the quotations outside the Western genre have gone unnoticed: the end is lifted from Benjamin Christensen’s The Devil’s Circus (1926). The idea of a sneaky revenge is inspired by Bresson’s Les Dames du bois de Boulogne (1945) and Sternberg’s The Shanghai Gesture (1941). It was the end of La Religieuse (1966), revised by Rivette, which gave me the idea of the heroine’s abrupt fall.

I loved the shot of Marie-Christine, in the middle of the desert with its canals, washing herself in a totally unrealistic green lake (the work of my props person Pinon). And the one where we see an isolated tree in the middle of a canal, which was a geographic absurdity. I had made a surrealist film. Which was confirmed by my color timing, done all alone without either of the cameramen, where I did not aim for color continuity from scene to scene, the goal of most filmmakers.

*

In the end, Billy was broadcast on French TV 10 years after the shoot thanks to my friend Claude-Jean Philippe, who really liked the film. And during a matinee retrospective of my films at a tiny Parisian theater in 2002, Billy was the one that did the best: an average of 16 tickets sold per screening!

To fulfill the request of Ramiro Cortes, a Mexican distributor who subsequently went bankrupt, I made an English dubbed version called A Girl Is a Gun (a tribute to D.W. Griffith’s slogan), which accentuates the film’s parodic side.

In the end, for a cost of around 230,000 francs, Billy ended up turning a small profit after five decades, even without having a true release in French cinemas. And most foreign distributors did not release it, although I still hear about outdoor screenings in the suburbs of Niamey followed by long ovations… For films to do good business is often unrelated to the number of viewers. A film’s distributor sometimes takes in more cash with 10,000 tickets sold than with 20,000, a result one often obtains thanks to a large number of prints and ruinous advertising. Billy le Kid’s box office (just like Origins of a Meal) was more positive than that of large productions which would have sold far more tickets while also having much higher distribution costs.

This chapter from Luc Moullet’s Mémoires d’une savonette indocile is translated and republished here with the permission of Capricci Editions and Luc Moullet

Share: