Michael Roemer

Interview

Michael Roemer

Interview

BY

Melissa Lyde

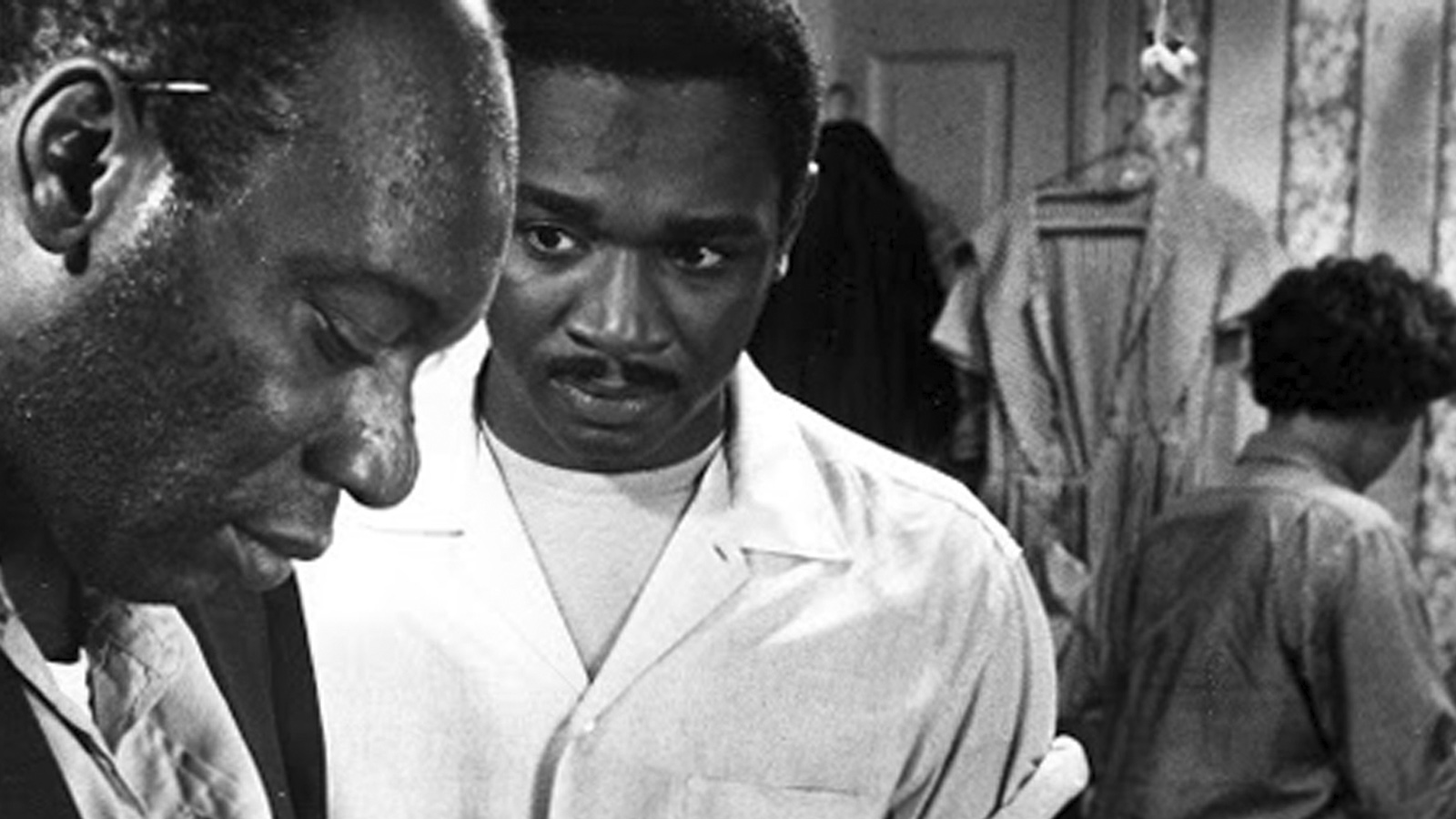

The director, co-writer, and co-producer of Nothing But a Man talks about the inception and making of his groundbreaking 1964 debut feature.

Nothing But a Man screens at Metrograph from August 13 as part of The Process, our series paying tribute to Robert and Irwin Young.

I was invited by Metrograph to interview Michael Roemer, the director of Nothing But a Man. This is an excerpt of our almost two-hour discussion, edited for brevity and clarity. The film was Michael’s first feature and he considers the experience of making it as a time of learning and invention. And what came from it, in my opinion, is a timeless masterpiece. Nothing But a Man is championed as a daring portrait of Black life during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. And as much as it is that, to me, it is also one of the most prideful romances of our time. It was Michael and co-writer Bob Young’s intention to give these characters dignity—you can see it in the dialogue, the performances, the lighting, and especially the documentary-style cinematography. Their new approach shattered Black stereotypes as previously portrayed in Hollywood. And it‘s the reason the film continues to resonate with audiences decades after its release. —Melissa Lyde

I ABSOLUTELY LOVE THIS FILM. I KNOW YOU GET THAT A LOT, BUT IT’S CINEMA HISTORY AND IT’S MY PRIVILEGE TO TALK TO YOU ABOUT IT.

Well, I do want you to know that I feel humble about my whole relationship to this project because I didn’t start it. I went on it because my friend and partner [Robert Young] had never made a fiction film. And my background was in fiction.

My acquaintance with African Americans at that time was close to zero. I was born in Europe, but there were things in my own past that were close to what I knew about Black life. And not only in the [American] South—it could have been made in the North with a different economic and social situation. It seemed rather across the board. But we were in the South, and I saw that there was this story that I had actually written before we ever went. It was about my own family and it was absolutely pertinent to what was going on.

I READ A LITTLE BIT ABOUT YOUR BACKGROUND, GROWING UP IN GERMANY AS THE NAZIS CAME INTO POWER, GOING TO ENGLAND AT THE AGE OF 10, AND THEN COMING TO THE STATES.

My father was pretty much like an African American male, unable to support his family for historical reasons. I mean anti-Semitism.

I rewrote my story, and Bob of course was very much involved. Everything fit. I know it sounds really strange, but in many ways, it was my story, my family’s story, and I kept recognizing it.

WAS YOUR FATHER AN INSPIRATION FOR DUFF’S CHARACTER?

My father was more Duff’s father, Will, in the movie. My father was an utter failure and very destructive and also very angry. I didn’t meet him until I was 25. I was always told he was evil and that I would be like him. It was horrible. I am going into very personal stuff, I shouldn’t be doing that. But I saw that he was a victim, when I met him. And that, of course, is how we felt about Duff’s father...

But I think we put a very positive spin on the family situation. There were two people in Mississippi who caught me very forcefully, two extraordinary civil-rights workers who were a married couple. The man’s name was James Bevel. He was a minister and his wife was one of the sit-in leaders in Tennessee. But at this point they were living at the home of an NAACP leader in Greenwood, Mississippi. Unfortunately, as was so often the case in young families, the marriage didn’t work out. As soon as we left [Mississippi], I recognized what we could do. I would have to say that [the film] is a rather idealized version of what we would have liked to do.

“I DIDN’T CLAIM TO BE DOING THIS [MOVIE] OUT OF SOME ALTRUISTIC MOTIVE. I THOUGHT IT WAS A GOOD STORY, AND I WAS VERY PRIVILEGED TO BE ALLOWED TO TELL IT.”

JULIUS HARRIS, WHO PLAYS DUFF’S FATHER IN THE FILM, DELIVERS PROBABLY THE MOST STANDOUT PERFORMANCE OF HIS CAREER.

Julius and I had a very good relationship. He was walked in by someone who was inexcusably left off the credits on the film. Chuck Gordone was his name. He was actually the guy who brought in Abbey [Lincoln], Ivan [Dixon], and Julius. We owe all three of them to him, and how we could leave him out of the credits, I don’t know, but we did. It was just neglect. I’m glad you now know about him.

THE CASTING IS ICONIC. I THINK IT’S ONE OF THE MOST PROFOUND BLACK ENSEMBLES I’VE EVER SEEN ON SCREEN. YAPHET KOTTO! AND THESE ARE SOME OF THEIR FIRST OR SECOND PERFORMANCES. THIS IS ESSENTIALLY A DISCOVERY OF IMPRESSIVELY TALENTED BLACK ACTORS.

Well, I have to say, Julius was not an actor, he was a male nurse. You can’t believe how few Black performers there were, especially men over a certain age. Canada Lee was number one, he was all there was. So when Julius came in, I was willing to work with anybody.

And Ivan was incredible. We would only do two takes with anything involving him. Chuck had suggested Ivan a while back. But I saw the performance he gave on The Defenders, which was not good at all, so I thought, “Well, no, I don’t think we should get him.” What I realized later was that he had been very badly directed, that the part wasn’t good. You can’t be good in a bad part.

I’m also not a hundred percent comfortable with the way the part [of Duff] was written. It’s too pure. It’s too perfect. I feel the same way about the part of the young woman, Josie. If you ever get the script, you’d see there’s nothing there. If it weren’t for Abbey, there wouldn’t be anything.

ABBEY LARGELY COMMUNICATES THROUGH BODY LANGUAGE. SHE STYLED A GENTLENESS, ALMOST A SHYNESS—WAS THAT SOMETHING SHE CONSTRUCTED FOR THIS CHARACTER?

I don’t think anybody said anything. I love Abbey. She and I became real friends. We had two weeks of rehearsal and I said right at the beginning to the assembled cast, “Look, I just want you to know, that I’m not doing this for you. I’m doing this for me.” Because I didn’t want the whole idea that I was a big civil-rights advocate who was doing this to advance the freedom of American Blacks. And as soon as I said that, Abbey came over to me, and I didn’t know her, and she gave me a hug. And that was the beginning of our working relationship. I think she was glad that I didn’t claim to be doing this out of some altruistic motive. I thought it was a good story, and I was very privileged to be allowed to tell it.

THIS FILM IS A REMARKABLE PIECE OF VISUAL ART THAT REFLECTS BLACK LIFE SO INTIMATELY AND REALISTICALLY THAT YOU WOULD THINK A BLACK PERSON WROTE IT. AND THE INTERNAL STRUGGLE IS THE MOST DYNAMIC ASPECT OF THE FILM: HOW DUFF’S ANGER SLOWLY BUILDS, BECAUSE HE’S TRYING TO DO HIS BEST AS A MAN, TO EARN A LIVING, BUT HE’S STILL TETHERED TO THE CONFINES OF OPPRESSION AND CONTINUOUSLY BULLIED BY THESE OUTSIDE FORCES.

I always feel guilty and a little like a liar because people give me credit for my ethical intentions. I mean, I don’t want to be contributing to the terrible things that go on in this world—I want to be on the side of the angels—but I’m very selfish. You want to do something good because it’s got your name on it. That’s part of it, but I do believe in the truth, and I’m trying to tell it. I believe that, very deeply.

ONE OF THE MORE PRAGMATIC INCIDENCES ABOUT THE FILM’S RELEASE WAS THAT IT WASN’T SHOWN TO BLACK AUDIENCES.

Filmmakers don’t have a lot of power and we had a pretty big debt when we were done. Nobody really wanted the film. The guy who took it on has seen it in Venice and wasn’t at all sure he wanted it. But when the New York Film Festival showed it and it was well-received, he picked it up. And he was not a good person. He owned theaters and he would put an enormous amount of money into advertising. The theaters would be full, but we never made any money except for the advance that we used to pay back the debts we had.

I remember going to Philadelphia and talking to people, mostly at midnight in closed buildings where there’s a little radio station and a guy with a phone and a microphone, and you wait for people to call in. I asked, “Why are you playing the film in this area? It’s entirely white, suburban.” And they said, “Well, we don’t want any Black people in our cinema.” And that was the story all over. The film kind of died. It didn’t really get seen very much. The liberal audience, white audience saw it, the college towns saw it, but nobody from the Black community saw it.

WELL, THERE IS ONE PERSON IN THE COMMUNITY WHO DEFINITELY SAW IT AND GAVE THE FILM HIGH PRAISE: MALCOLM X.

Yeah, a few days before Malcolm X was shot, he ran into Julie [Julius] on the street and said, “You’re in Nothing But a Man.” And Julie was delighted and he said, “Yes.” And Malcolm X told him he liked the film a lot. Muhammad Speaks also gave it a very good review, though they never said who made it.

CAN YOU SHARE THE WRITING DYNAMIC BETWEEN YOU AND BOB? DID HE CONTRIBUTE TO THE RACIAL-TENSION SCENES?

No, I wrote those. I have a lot of anger in me and it comes to me very naturally. I can write anger by the ream.

I DIDN’T WANT TO SAY IT, BUT THE SCRIPT DEFINITELY SEEMS LIKE AN ANGRY PERSON WROTE IT.

Yeah, well, that’s me. I think it was a good thing that there were two of us. Bob was behind the camera and he balanced me out. Look, art and anger are not unrelated. I wrote the father out of anger. Anger at my father, I suspect, but also the fact that one understands that anger is misplaced. My wife wrote some stories and at the end of one she said, “At last, nothing to forgive.” And I always, think of that. It’s true. Duff’s father is not guilty.

BUT YOU WERE ALSO BUILDING THIS PERFECT REFLECTION OF TWO YOUNG BLACK LOVERS DEALING WITH THE TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF RACISM AND GRAPPLING WITH THEIR OWN ADULTHOOD.

Yeah. But one of the things that I feel is not in the film, is the anger of a woman. It’s sort of a side issue because Abbey is so sensitive to the issues of the males. The anger of many African-American women can get misdirected at the men rather than at the system. There was an expression about African American woman, that they were evil. Did you ever hear that?

NO, BUT IT DOESN’T SURPRISE ME.

It meant that an evil woman was an angry woman—and there were many good reasons for women in your community to be angry. I was the object of an angry woman myself as a child.

And many young African American boys were raised by their grandmothers. It’s a story that I feel very deeply myself. My father had no parents or had absent parents. They were absent because they were high and mighty, not because they were downtrodden, but it’s the same story. You still have no parents. And, I mean, all of my films are family stories, and most of them are about bad families. You know, that’s the source of my anger. And I was lucky. I met my wife, who died 14 years ago, but she made my life possible.

At a big conference, many years ago, a woman raised her hand in the back of the room and said, “What about anger in women?” And I just said, “We failed to include it.” It’s there in the neighbor’s house in one scene where the neighbor’s wife yells at her husband who works at the mill with Duff. It’s just a moment and that’s the only time.

IT IS INTERESTING THOUGH THAT YOU DISCUSS THE ANGER WITHIN. THE FILM DOES LACK EXPRESSIVE ANGER FROM BLACK WOMEN. ONE OF THE MORE OBVIOUS STANDOUTS AMONG YOUR ENSEMBLE IS GLORIA FOSTER AS LEE, WILL’S GIRLFRIEND. SHE COULD HAVE EASILY BEEN A VERY ANGRY ENTITY FOR THE FILM. BUT I DO THINK THE ANGER IS THERE, WITHIN HER. IT’S BEING SWALLOWED AND YOU CAN SEE IT WANTS TO COME OUT. THAT’S WHAT I SEE A LOT OF BLACK WOMEN DOING—I THINK THAT’S ONE OF THEIR EXPRESSIONS OF ANGER TOO.

I think that’s absolutely true. And it was a strange business with Gloria because I had to keep turning the faucet down because she has so much feeling and wanted so much just to open up the faucet, and I kept saying, “Gloria, just close it out.” It was the only part for which we had like three possible actors and it wasn’t the easiest to fill. Gloria came in and said, “I’m going to play Lee.” And I said, “How do you know?” And she said, “I tell you right now, I’m going to play that part.”

“I HAVE A LOT OF ANGER IN ME AND IT COMES TO ME VERY NATURALLY. I CAN WRITE ANGER BY THE REAM.”

WE’VE BEEN ON A LOT OF THE INTERPERSONAL DYNAMICS BETWEEN THE CAST, BUT I ALSO WANT TO DISCUSS MORE TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF THE FILM, LIKE THE CINEMATOGRAPHY. THE LIGHTING IS SO DARK, YET, IT’S VERY DIRECT ON EVERYONE WHO’S IN FOCUS—IT’S STUNNING.

Bob really loved everybody and loved to light them so that that love came through.

AND IT WAS VERY RARE FOR BLACK PEOPLE TO BE IN FOCUS OR TO HAVE A CLOSE-UP.

We were very determined to make a film in which you would look at African American faces and that you would be close to them. We were very deliberate about that. And, as I said, Bob lit everybody with love... While he was lighting, he would be very, very careful. The stock was much less fast than it is now. Also, Bob had never shot a feature. We were just going with what we thought was right. And the sound was done by the first person to use radio microphones on a feature film. Nobody was doing that.

I WOULD LOVE TO GET YOUR REFLECTIONS ON THE MOTOWN MUSICAL SCORE.

A college friend of mine [George Schiffer] went to law school and he said, “I just became counsel to a record company in Detroit and you should listen to the music. Maybe you can use some of it.” And he gave me a stack of 45s. I went home with them and listened, and I said, “Jesus, this music is marvelous.” And George arranged for Motown’s Berry Gordy to invest the equivalent of what it would have cost us [to license the music].

But at the first screening, there were like three or four well-known people who said, “You can’t use that music,” so I got cold feet and I started talking to a composer about writing a score. And then a friend of mine, who later on did a lot of work with me, said, “You’re wrong, that music is wonderful.” So I went back and used it. I mean, I believed in it too. It was not yet known to the white community. But by the time the film was released, Motown was a big deal. And I think Motown was always pleased to have its name on the film. They even made some money.

THIS FILM IS ABSOLUTELY PRAISED BY THE COMMUNITY, AND IT’S A BENCHMARK FOR SO MANY YOUNG ACTORS. WHAT DO YOU THINK OF THE RECENT RECEPTION AND THE IMPACT IT’S HAD ON PEOPLE?

It hurts a little bit to make a film at the wrong time. Nothing But a Man didn’t get shown the way it should’ve been for at least 16 years, and possibly longer. It was New Video that picked it up a good 20 years later. They opened the film at the Apollo on 125th Street. There was a crowd. Ivan was there, and Ivan always said to me, “I’m so glad I made this film.”

As soon as we did a screen test with him and Abbey, we were so happy. We knew that the film would work with those two people.

Melissa Lyde is from Brooklyn, NY and works in film distribution. She is the founder of Alfreda‘s Cinema, an ongoing series at Metrograph, and produces similar programs around New York.