From the Magazine

Luxurious Realism: Mark Lee Ping-bing

The legendary Taiwanese cinematographer breaks down two inspiring scenes.

Mark Lee Ping-bing. at the Metrograph Commissary. Photograph by Maria Spann.

Share:

This interview appears in Issue 1 of The Metrograph, our award-winning print publication. Explore more of Issue 1 and newer editions here.

OVER A SIX-DECADE, ACCOLADE-FILLED CAREER, Mark Lee Ping-bing’s collaborations with directors such as Wong Kar-wai, Trần Anh Hùng, Ann Hui, and most notably, his long partnership with Hou Hsiao-hsien, have inspired a rising generation of cinematographers—amongst them the Baltimore-based Bradford Young, whose elegant DP work in films such as Ain’t Them Bodies Saints (2013), Selma (2014) and Arrival (2016) has garnered widespread praise.

Young quizzed his hero on two films directed by Hou and magisterially shot by Lee: Flowers of Shanghai (1998)—a quietly devastating work of placid surfaces with violent emotions roiling beneath, which takes place in a candle-lit, opium-drenched den of 1880s Shanghai, following a group of high-end “flower girl” courtesans and their wealthy patrons, one of whom is played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai—and Millennium Mambo (2001), a stylish and seductive submersion into the techno-scored neon nightlife of Taipei, starring Shu Qi as an aimless bar hostess drifting away from her blowhard boyfriend.

In the later film, Lee and Hou break from their familiar pattern of elegantly composed long shot long takes and dreamy floating images, instead using shallow-focus, jittery camerawork, and cramped locations to create something both more intimate and hectic. To dissect the two films more closely, Young selected a scene from each that was particularly meaningful to him, and Lee generously broke them down frame by frame, offering an inside look at the machinations of his working partnership with Hou, and revealing how they bring their joint vision to the screen. Thanks to Vincent Tzu-Wen Cheng for his assistance translating.

Mark Lee Ping-bing and Bradford Young, photograph by Maria Spann.

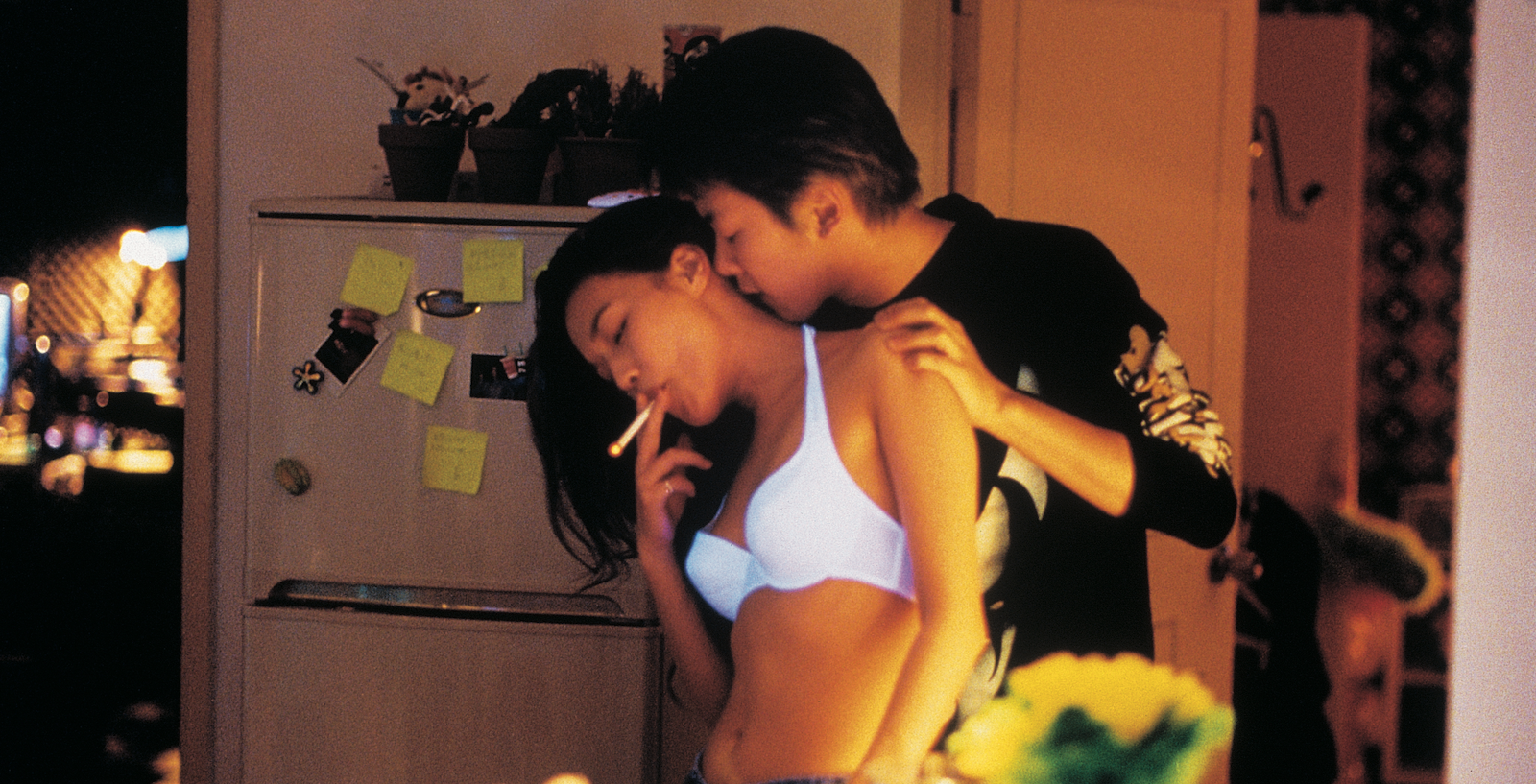

Millennium Mambo

MARK LEE PING-BING: Director Hou and I shot this film in the year 2000—and of course, its name is Millennium Mambo. We started by wanting to capture the essence of the time: welcoming this new millennium, talking about hope for the future. But we also wanted to capture the emotions of the younger generation who seemed then so disoriented, so adrift. That’s why, in this scene, the camera movement is a little shaky, that’s intentional. It’s to represent their anxiety, their excitement, their restlessness.

The other thing we wanted to capture was the idea of the new digital era: we believed we were entering the era of digital filmmaking. Back then, we were not very well-versed in digital filmmaking—myself, especially—but we knew it was the future. We thought it would be a cool idea to make a film that had this digital feel, that digital texture, but to achieve it by using film stock. That’s why we chose to use cold tones in the color scheme that you see in this scene. Also blackout lighting to block out light and better create this feeling of the almost digitized visual images that we were striving for.

We were thinking, too, about trying different ways of filmmaking using film stocks, we wanted to subvert a lot of the conventional thinking about what makes for good filmmaking. For example, usually post-production will remove things such as the visual noise that you see on a TV screen. But we thought things like that would actually convey this sense of anxiety and restlessness—digital noise is very on-brand, it really suits this idea of digital filmmaking—so we intentionally left them in.

Usually, for night scenes you would use very wide shots to have better control of your focal points and safely capture whatever it is you want to capture. To shoot this particular night scene, though, we decided to use a shutter speed of 1/35 [which risks making the image shake or blur], again to create this sense of uncertainty and unknown. We wanted to try something that had not yet been done so it would feel like we were doing something risky and new.

This idea was extended through to the way that director Hou works with his actors. Sometimes he would give them directions or suggestions, but he would never share those notes with us [the camera department] so we had to somehow in real time find a way to capture what these actors and actresses were trying to do. And since director Hou doesn’t really do rehearsals or test shots, what usually ends up happening is that I, as a cinematographer, have to anticipate where the actors might position themselves for parts of the scene, and how they might do their blocking in terms of how they move around in this small space. Of course, I also need to somehow share my predictions, coordinating with the sound recordist and the camera assistant to pull the focus so that we can get the image we want clearly.

Here, we were shooting in a hotel room. There were four different rooms within this particularly small space. Because of this, my lighting setup was very simple. I wanted to give the actors the largest amount of space possible so that they had the freedom to move however they wanted. For this particular shot, we had three or four takes. Director Hou gave notes to the actors for each take; these would be different each time, about things like timing or performance. And of course, I was not informed of how they were going to change for each take.

This method creates this feeling of instability, of uncertainty—of trying something new and seeing if it will work. Since I already had the lights and shadows set up the way I wanted them in order to create that digital feeling we were pursuing, I was forced to make decisions in the moment: how am I going to pan my camera? Where am I going to focus? How am I going to change the focus from one actor to the other? These decisions were all made in real time, organically, during the shoot.

Millennium Mambo (2001)

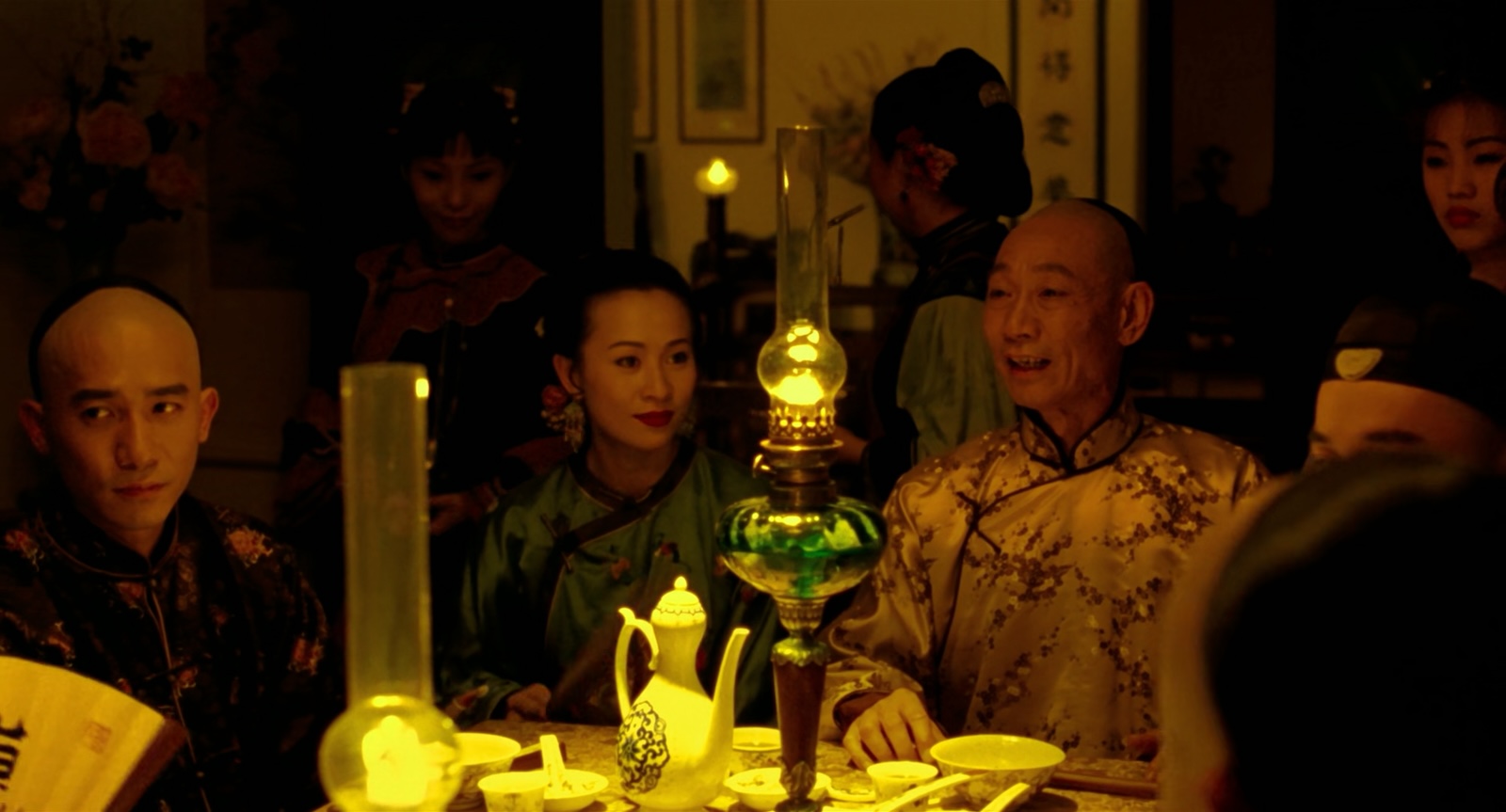

Flowers of Shanghai

MARK LEE PING-BING: The film takes place in a brothel, near the end of the Qing Dynasty. For this scene, there’s just one focal point: Tony Leung’s character, and how sad he is in the middle of this hustling, bustling brothel, and how deeply he is consumed by his thoughts. That’s what we’re trying to capture.

As you can see, many people are seated around this table. In terms of mise en scène, I think that the most difficult shots or the most difficult scenes to do are dining scenes. And it is especially hard when, like here, you have so many characters involved.

When discussing how we were going to capture this single focal point of Tony Leung’s character, with this very complicated eating scene going on at the same time, we asked ourselves, “How can we find a new angle, a new way, a new perspective for this scene?” I persuaded director Hou that we should set up tracks and do tracking shots. We had tried this in the past, but later I would always realize that he had removed all the tracking shots during the edit. So this was the first film I ever managed to persuade him to keep the tracking shots in.

What we were trying to do in this scene with the tracking shots was, again, to find a new perspective, to subvert what we’d done in the past. We didn’t want to repeat the conventional way of using tracking shots to capture actors speaking—i.e, whenever someone is speaking, you pan and move the camera towards this person, and then move the camera back to the other person when that person is speaking. So we decided to use the tracking shot, but at the same time we wanted the camera to move without a clear purpose. The camera is moving organically, for example, maybe not framing the person who is speaking. At the same time, watching this scene, you feel as if the camera is moving constantly. But really, it is not moving all that much.

Since this is one continuous uninterrupted shot, the biggest challenge was to think about how we were going to move naturally, without purpose, but then for us to always come back to Tony Leung’s character and capture his sadness. In terms of the performance of this group of actors around the table, a lot of what they were saying was improvised, except for a few key points that they had to mention. We needed to somehow deal with the fact that we did not know who was going to say what or when, and then, very carefully but naturally, to continually return to Tony Leung’s character at the end.

This is how director Hou works, there are no rehearsals. We try a few takes, and each time make adjustments to find the best way to capture the dramatic focal point, the feelings and emotions, and the mood of the scene. Usually director Hou will just say, “No, this is not going to work out. We are not going to include this in the film. We are going to edit it out.” To be always thinking about what director Hou wants in relation to the way the camera is moving while also still capturing all the different characters and to arrive at Tony Leung’s character at the end—it’s a lot of pressure! I kept asking myself: can I get what director Hou wants, in real time, within two takes?

Before we went into production, we talked for almost a year about how we were going to achieve the look of this film. Director Hou wanted it to resemble a Chinese-style oil painting, to have that gloss and saturation, that shiny, luxurious quality. At the same time, the most important thing for director Hou is always to be realistic. With his previous films, realism had always been his goal, and it is still for many of the films that follow. But for this film it was a contradiction to want to have something look so realistic but at the same time so glossy, so luxurious.

So we were trying to find ways to capture this kind of “luxurious realism.” How can I make an image that is luxuriously real? I did a lot of design work to achieve this effect, to make the image look like an oil painting. For example, I usually do a very simple lighting setup. Here, the lightbulbs in the lamp that you can see on the table, that light is not coming from the natural bulb. We actually had a spotlight focused on this table lamp. Then, it is the spotlight’s reflection that is captured. I was using a 2,000-watt spotlight, what we call the yellow headlight, trying to make the lamp become the light source. We cut a hole in a reflective board; through that, we pinpointed where the light [from the spotlight] went. Of course, some peripheral lights, different colors, would come through too. I wrapped it with temperature gel so that we could achieve the exact effect we wanted with this simple lighting setup.

One day during production, after we’d been shooting for quite a while, the editor talked to director Hou. They felt that this look was not realistic enough, that it was too luxurious, so he just turned that light off altogether and said, “This is real, so this is how realistically it should look.” I had this discussion with director Hou: “Before, you told me that you wanted the feeling of an oil painting or, like in Barry Lyndon (1975). But now, you want to turn it off?”

Can you imagine, it would have been so dark with just a simple lamp, and with actors dressed in late Qing Dynasty costumes; there would have been a lot of shadows, almost like in a horror or a zombie film. I didn’t think that was the direction we should go in, so I eventually persuaded director Hou to really accept this idea of what I called luxurious realism. It’s almost like a new concept to think about: can you look real but still glamorous at the same time? That’s what we were trying to accomplish with not only this scene, but this entire film.

Flowers of Shanghai (1998)

Share: