Interview

Mariama Sylla

A conversation with the filmmaker about her late sister’s dynamic portraits of those living on the margins of Senegalese society.

Share:

It was through writing that Khady Sylla found her way to cinema. In 1992, she published her first novel Le Jeu de la mer (The Game of the Sea), a magical realist tale about two young women who spend their time telling fantastical stories. French ethnographer Jean Rouch told her the book reminded him of the West African deity Mami Wata, but the script he and Sylla wrote together based on her novel never materialized. Instead, Sylla went on to make a handful of expressive, powerful documentaries and short films, many of them in collaboration with her sister Mariama. When she died in 2013, she would leave behind a small, but formidable oeuvre that chronicled everyday life in her native Senegal. Born in Dakar, Sylla used the camera or, what she called her “third eye,” as a therapeutic mirror for both society and herself. Although laden with the legacy of colonial intrusion, cinema became her tool for scrutinizing the margins to better illuminate the whole and what lies beneath: frequently, madness. Sylla herself lived much of her life with schizophrenia and endeavored to depict the loneliness of those troubled by mental illness, as seen in her harrowing 2005 documentary An Open Window.

In a patriarchal society, these margins are inherently female. The psychological, social, and economic effects of colonialism on Senegalese society are reflected in her films beginning with Les Bijoux (1996), which depicts a middle-class family and the aspirations of a young woman who dreams of fleeing to the West. With her final film, A Single Word (2013), co-directed with Mariama, she sought to archive the oral tradition of her ancestors, which she had previously honored in Le Jeu de la mer. I spoke with Mariama, a director and producer in her own right, about her late sister’s devotion to language, her compassionate portraits of those living with mental illness, and the women who so often took the center of their projects together. Our conversation has been translated into English by Mélanie Scheiner. —Marie-Julie Chalu

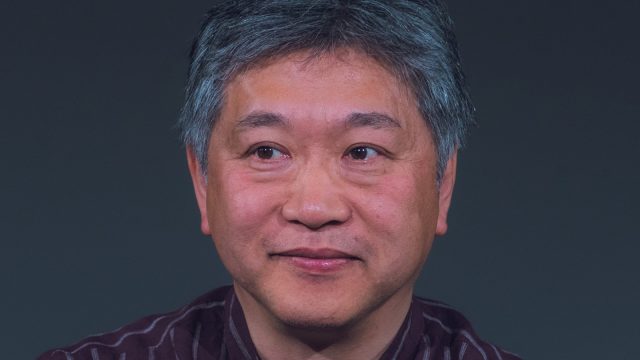

The Silent Monologue (2008)

MARIE-JULIE CHALU:When did you start working with your sister on films?

MARIAMA SYLLA: I’ve worked with my big sister Khady, who’s no longer with us, since I was 17. So I’ve been making films for over 25 years, mostly with Khady, but independently as well. We have our films together, I have films that others have produced, I’ve produced my sister’s films, and I’ve produced the documentaries and short films of others.

MJC: What are your first memories of cinema? And in what ways did they serve as models, or counter-models, in your artistic practice?

MS: Our first experiences of cinema came from our mother, since she worked for the Direction of Cinematography [part of the Senegalese Ministry of Culture] in the ’60s, just after the country gained independence. We were exposed to cinema since our mother at the time was an executive secretary and the only one who could type up scripts for the filmmakers, who were often at our house. She worked with Ousmane Sembène for eight years at his production company, Filmi Doomireew. For example, she typed the scripts for his films Mandabi (1961) and Camp de Thiaroye (1988). And in the 1970s, filmmakers Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, Djibril Diop Mambéty, and Ababakar Samb, all used to come to our home.

MJC: You’ve said that you began working with your sister at age 17, can you tell me about the origins of your collaboration?

MS: In the ’90s, my sister came back from studying in France and wanted to make her first short film. It was called Les Bijoux, and it ended up becoming almost a family film. Me, my older sister, some cousins, friends—we all acted in it to support her, because it was funded by the GREC (Groupe de Recherches et d’Essais Cinématographiques), and it had a very small budget that could only cover the director of photography, the sound recorder, and the gaffer. So, to make it work, all of us came together to support her.

I play a young, eccentric girl who wants to go live in Europe or the United States, since that was the desire of the Senegalese youth at that time: El Dorado was elsewhere. The film is a sort of microscopic look at a Senegalese family in which the mother, the brother, the sisters, and cousins all pay a visit, and it all revolves around a pair of lost earrings.

There are little stories that happen within the family: for example, there’s a maid who’s accused of having stolen the earrings, because often in Senegalese families, when something is stolen, we never accuse family members. Rather, it’s always the outsider, meaning the housekeeper. So Khady really touched on these details of Senegalese domesticity in a very short space, 17 minutes.

MJC: Yes, the class dynamics are clearly visible. Watching her films, I felt a sense of melancholy, of wandering. Khady herself lived between France and Senegal. How did these themes translate cinematically?

MS: It’s her life, because she lived between two worlds. She went to France and was shocked by it. She spoke of a “chromatic” shock when she arrived in Paris, meaning that she immediately sensed the differences between Senegal and France on every level, even if she really enjoyed being in France. I think that experience left a deep mark on her. That’s where her desire to return to Dakar, as early as 1993, ’94, came from. From the mid-’90s onward, she would only go back to Paris for maybe two weeks, a month at most. She could no longer live in France.

The reason her voiceover works so well is that Khady, first and foremost, saw herself as a writer before seeing herself as a filmmaker. She started out writing. Her book Le Jeu de la mer was published before she made any films. She was gifted as a writer and knew how to use language, how to wield words. That became one of her strengths and enriched her filmography once she moved into documentary filmmaking. All her documentaries are long, flowing narratives, between 30 to 50 pages each. She truly wrote them out; you could turn them into fiction scripts. And strangely, most of the time, when we arrived on location, things would unfold exactly as she had written.

Especially in Colobane Express: most of the scenes are real moments that just happened naturally. People got into the car rapides, started talking, having conversations, and it all flowed as it had been scripted. That’s what makes her work so beautiful. There’s so much poetry and a dreamlike quality as well.

MJC: This translates into the way that art and life are intertwined in her cinema. They are not two separate things.

MS: Yes, for example, An Open Window (2005), where she becomes a character in her own film: she wanted to do it because she wanted to give a part of herself, to show that she—as a mentally ill person, a filmmaker, and a writer—also had her piece to say. She wanted to show how she was shaped by illness and how she was capable of forging a friendship with Aminta Ngom, who was also ill. So these are substantial slices of life.

MJC: In A Single Word, she says, “We’re making this film out of an overflow of humanity.” I see in that a deep generosity, for sharing, for building connection with others.

MS: That’s exactly it. As she said, we wanted to move from oral tradition to written tradition, because our grandmother—whom we were going to see in the film—belonged to another time, and we really wanted to share something with her. We grew up around her, but without truly capturing the words she spoke to us. And cinema is about the human being. The human is at the heart of cinema.

You can’t make cinema without speaking of humanity. If it’s not grounded in humanity, then we can’t create something to offer to others: something that they can receive, transform, and return in another form.

An Open Window (2005)

MJC: Cinema, as a tool, is also linked to a history of colonialism. The history of African cinema is laced with how filmmakers from the continent had to reappropriate this tool that had been used to assimilate and subjugate them. I wanted to ask you about the production of the films: how were you able to produce your films independently in order to maintain creative freedom?

MS: That was very difficult. Firstly, because independent cinema is always challenging, and additionally we had several misadventures with producers where it went badly and we ultimately had to drop the whole thing. But in my case, for Les Bijoux, it wasn’t complicated because at the time, the GREC offered a little support, as I mentioned. When you showed up to make the movie, you knew you could at least pay the technicians. And then for the rest, if you’re surrounded by a supportive environment, which was our case since the people in our family were familiar with filmmaking and had a sensibility for it, knew what we were talking about, had seen films, etc…it was a lot easier to talk our sisters, our cousins, our friends into participating and acting in it. Everyone who acted in Les Bijoux had no formal training, they were amateurs like Aminata Sophie Dièye, who is also a writer; she wrote a magnificent book called It Rains on Dakar.

For Colobane Express we had a production team, so that was a bit calmer. That film was one of the more straightforward ones to make. Whereas for An Open Window, it was more complicated because we had the project, we had pitched it around, and no one would take it because they were concerned with how to depict mental illness, when the person depicting it is mentally ill herself. How is she going to film this? How is she going to film herself and others? It’s a project we held onto for five or six years without finding producers. At the time, I knew nothing about producing. Then in 2000, I said: “Listen, Khady, I know nothing about producing, but I’m going to train as a producer, and we will start a production company, and then see how we can do this ourselves.”

That’s how our production company Guiss Guiss began. It’s a Wolof word that means vision or clairvoyance. Khady found the word, and she defined the [spirit] of the company. I did a production training course called Eurodoc, even though I wasn’t really eligible for it, but this is an opportunity to thank a wonderful person who is also no longer with us, named Anne-Marie Luciani. When she received An Open Window, she read it and called me, saying, “We don’t accept African producers because this is a course on European production but I read the project. If you can, buy your ticket, and come pitch your project to the decision-makers here.” So that’s how it happened. I went to Strasbourg, and it was picked up by the television channel Arte. The programmers of La Lucarne [an Arte series dedicated to experimental documentary film] said that it spoke to them, so they took it. It was really a stroke of… how to say it? There was luck, but there was perseverance too: pushing for things and fighting for it.

MJC: Childhood is a recurring theme in Khady’s films. What did that represent for her, according to you?

MS: She’d say, “Childhood can last 30 years, I know. I lived it.” She and I really had an extraordinary childhood. It was surrounded by tons of artists: we’d converse, watch films, look at art. At 30-years-old, when she became ill, that’s when her childhood ended. I think that’s when it ended for everyone in our family. Because everyone became involved in trying to protect her, saying that we had to keep her surrounded so she wouldn’t wilt. Our great fear here in Senegal is that the sick aren’t well looked after. You can see that in An Open Window. But we all came together, just as we did to make Les Bijoux. We formed a bloc around her so she could pursue her treatment and continue to make her films because she had a lot of projects on the docket. In emerging from childhood, she made us also leave our childhood behind. Our only objective was that she remain stable, that she continue to be able to write and make her films. I think that until the very end, we managed to do it together: the family, the close friends.

MJC: Why is she called the “daughter of water?” It calls back to Le Jeu de la mer where it is a recurring motif. Why the nickname?

MS: That comes from our mother. It’s something we inherited from her because our mother was a “daughter of water.” A “daughter of water” is defined as a simple, sensitive person who can be a bit set apart from the mainstream world, who has a different perspective on life, on family, on sharing, on being human. So for us, that came from our mother. All the girls in our family, including Khady, inherited a bit of that.

MJC: You also inherited this outlook?

MS: Precisely, this particular view of the world where everything is connected to simple things. And, as you said earlier, to things such as exchange, a giving of oneself, of being close to others, sharing with others.

MJC: I also like the phrase she used to refer to the camera: the third eye. We often speak of the split personality in schizophrenia, and it’s as though the third eye allowed her to unite these two personalities. In An Open Window, she talks about broken mirrors and how to relate to them.

MS: As she said, literature saved her life, but cinema allowed her to organize all these fractured moments that she held in her mind, which is where the utility of the third eye came in. I think that the camera gave her more agency over her ideas, an ability to group and organize her thoughts into moments like An Open Window, The Silent Monologue, or A Single Word.

MJC: In The Silent Monologue, there’s a real analysis of how housekeepers working for Senegalese families endure capitalist, class, and patriarchal oppression.

MS: Yes, precisely, that’s also the analysis of women in general, who aren’t necessarily domestic workers. We were amongst the rare women who managed to break out of this structure, but the majority of Senegalese women live under the yoke of patriarchy. Even if we see Amy coming to Dakar to work, it’s under the thumb of the patriarchy. There is the father or husband who’s going to ask you to go be a maid to earn some money. She even talks about it at the end of the film, when she returns to the village with her baby, she continues to do the same reproductive labor but for no pay. And it’s shocking to no one. So there, I think of all our films, The Silent Monologue is the most feminist.

MJC: We also see in Khady’s cinema the changes brought by colonization on Senegalese society, which is already present in Les Bijoux. It reminds me—you’ve surely been told this already—of Safi Faye’s films. Specifically, the way she depicted how food self-sufficiency is undermined by agrarian politics inherited from colonialism, and thus contributes to a rural exodus. In A Single Word, you return to your grandmother’s village and attempt, through cinema, to either pay homage, or in any case, to archive the oral tradition.

MS: Yes, yes, it’s a fight against annihilation, to capture it so that it continues to exist. Most of the time, they are things which, as you said, will disappear. They are moments and situations that are important to our lives, that should remain. To fight by all means necessary against their disappearance, to be able to preserve what people consider banal. It’s not banal, it’s extremely important to Senegalese society. It’s fundamental even for the development of the consciousness of the youth who will replace us tomorrow, so it’s very important.

MJC: So how do you continue to combat this annihilation?

MS: I’m working on my next feature film, which is called Khady Sylla, the Daughter of Water. It’s a feature on her, on her life, her writings, her films, friends, and family. I’ve been working on it for two years. Maybe the film will come out in 2026; it will be my sixth. Otherwise, I made a short film called Hors série, followed by a documentary on a Senegalese sniper called Tirailleur Marc Gueye, who wrote a book about the First Indochina War. Afterwards I also made a short film called Dakar Deuk Raw. It’s about the Lebous, a Senegalese fishing community, on how they were the first inhabitants, and about the changes that the city of Dakar has undergone.

MJC: Do you use cinema as a tool of decolonization?

MS: No, maybe. It’s not like that because we are a generation born after Independence. What we can feel is, maybe, what we could call neocolonialism, but not colonialism itself. Because actual colonialism, that’s what our parents lived through, and we didn’t. When we were born, colonization was over. But the tools of colonization remained. Take the Senegalese schools, for example: that’s a tool of colonization. The way we are educated in Senegal, it’s the same instruction that the colonizers left behind here, despite some little changes. So maybe we were raised, as you say, that we picked up a tool that the colonizer left behind to tell our own stories and our own lived experience, and the lens through which we see Senegalese society that we want to transmit back to it, that we want to show to the world. That’s what most motivated us to make films.

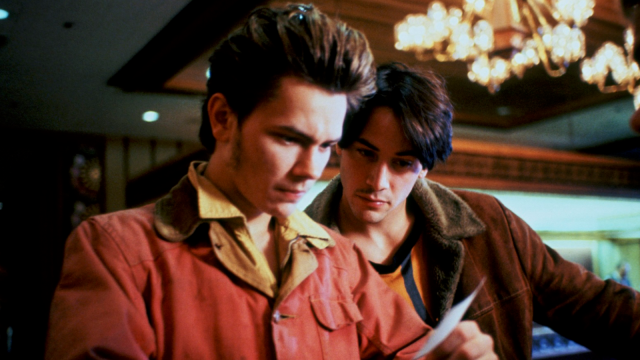

Colobane Express (1999)

Share: