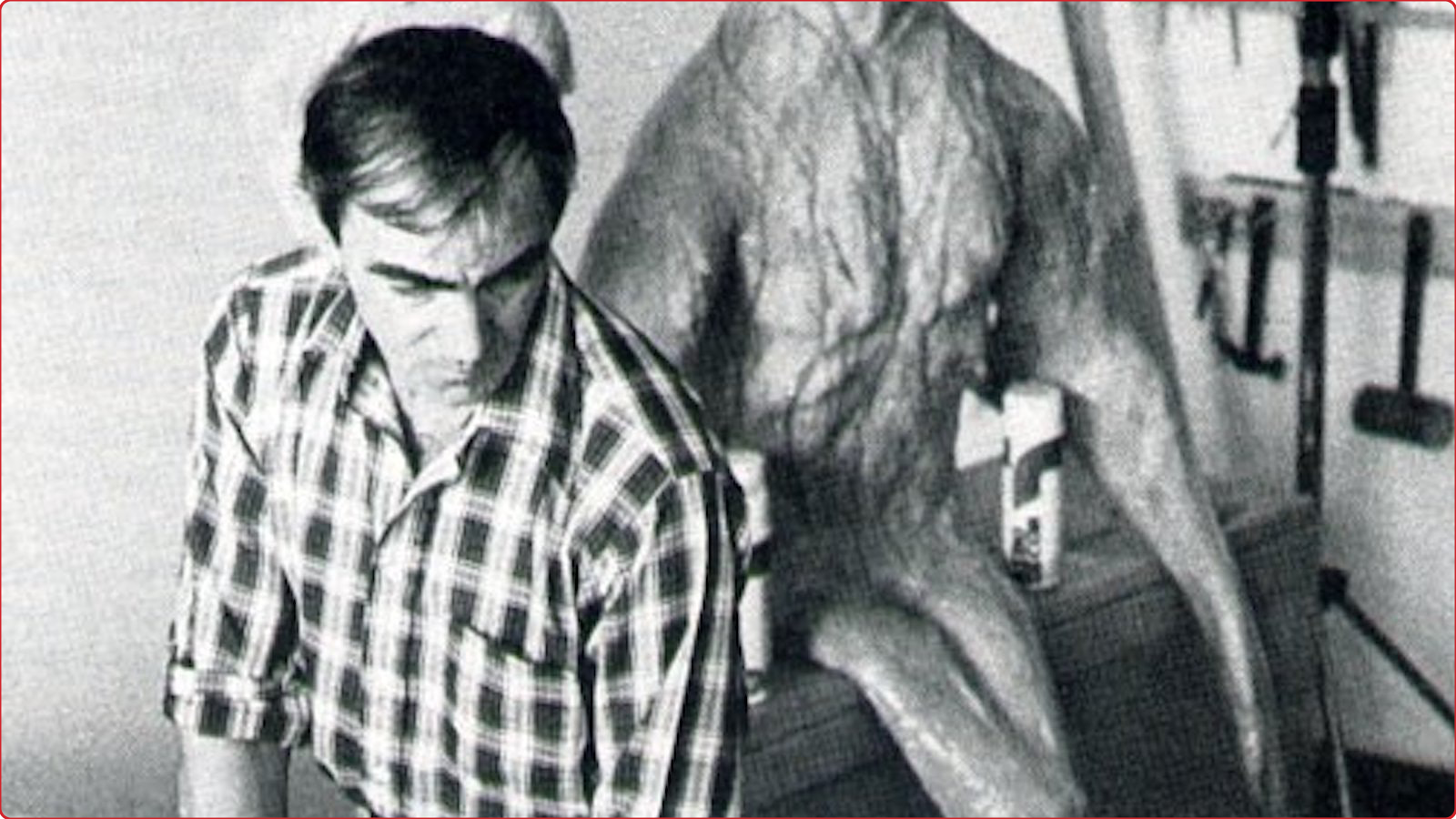

Andrzej Żuławski creating the monster in Possession

Excerpt

MAKING A MONSTER

By Daniel Bird, Serge Toubiana, and Pascal Bonitzer

An excerpt from an interview with Andrzej Żuławski published in Cahiers du Cinema in May of 1981.

Possession plays at Metrograph as part of Halloween at Metrograph, and streams exclusively at Metrograph At Home.

It was the French producer Christian Ferry, then working as an advisor for Charlie Bluhdorn, head of Gulf and Western, who secured the money for Andrzej Żuławski to develop the original English language script that would become Possession (1981). The screenplay was initially drafted by Żuławski while staying at the Mayflower Hotel in New York City, although he later moved to the Gramercy while writing the final draft with novelist and New York native Frederic Tuten. Initially, Żuławski pitched Possession as taking place in Detroit, a city where Bluhdorn owned factories, and one which was and is home to a large Polish expat community. Bluhdorn ultimately passed on the project, and Żuławski found a French producer who tried to set up Possession as an English language French-Canadian co-production. When the financing collapsed, Ferry remembered a young French producer, Marie-Laure Reyre, who he had met during a preview screening of King Kong (1976), a film on which Ferry was a producer. It was Reyre who secured co-production funding to shoot in West Berlin from the Berlin Senate. After tentatively exploring the possibility of shooting in Dallas with the backing of then newly created Orion Pictures, Reyre secured the rest of the funding in France. Despite thinking that Possession, by virtue of shooting in English, would reach a broader audience, the very opposite turned out to be true. While Possession underperformed at the French box office, its fate proved much worse in the Anglophone world. In England it was briefly considered a “Video Nasty,” subject to a legal proceedings by the Department of Public Prosecution before the case was eventually thrown out. Possession was finally released in North America two-and-a-half years after its Cannes debut. It was not, however, the version which had screened in Cannes that was released, but rather a radically different edit complete with newly recorded dialogue; a wailing, Omen-style score; and kitschy optical post-production effects. Courtesy of Metrograph, Possession has finally received a proper North American theatrical release, four decades after its Cannes premiere.-Daniel Bird

“I therefore found myself alone in a hotel with a typewriter and a lot of whisky, and I wrote very quickly this screenplay that I had been carrying for quite a long time.”

What follows is an excerpt from an interview with Żuławski conducted around the time that Possession premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival in May of 1981. In this interview, conducted by Pascal Bonitzer and Serge Toubiana for Cahiers du Cinéma No. 326, Żuławski traces the origins of Possession, first as a draft script in Polish written in Warsaw, then recast in English.

CAHIERS DU CINEMA: Can we talk about the technical creation of the actual monster [in Possession], because it’s done quite well.

ANDRZEJ ŻULAWSKI: Yes! Well, it was very difficult and very complicated! It was difficult because I found myself in front of technicians, to whom I had to explain that it should not look like anything known. But to look like nothing known means to look like what? I wrote this script in New York, by an absolute coincidence; my film [On the Silver Globe] was stopped in Poland, and when I was given a passport, the only place I could go, where I had friends who wanted to welcome me at that time, was in New York, it was a perfect coincidence. I therefore found myself alone in a hotel with a typewriter and a lot of whisky, and I wrote very quickly this screenplay that I had been carrying for quite a long time.

I had thought about this script in Warsaw, with this story against the backdrop of a socialist universe, the great slogans in red, and this totally anti-Marxist story against the background of Marxism… And so I wrote it in New York and my friends had it read by several people there. I didn’t want to make an American film, I knew due to the American structures that I would easily get eaten up there, with the few films I made, the lack of financial performance of these films in the United States.

For purely financial reasons concerning the film’s budget, I found myself in Los Angeles: the producer [Marie-Laure Reyre] needed an American name for the special effects, she thought that this way the film would be better structured, would sell better; it was a very difficult film to finance, you know that nobody wanted it, it travelled around producers, they read the script, they said “But you’re completely crazy to want to do that!” So she had a hard time, and I understood why she turned to Americans, and also to Carlo Rambaldi, the guy who made Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), who made Alien (1979), King Kong (1976), who made a lot of good or bad films, it doesn’t matter, and who made 100 or 200 films in particular at Cinecitta (He worked with Fellini, he worked with everybody in the world.) And he’s an absolutely lovely guy, an Italian in Hollywood who has never learned English, who makes a lot of money, but who is full of good will, who is skilful with his hands, who finally wants to do something and who above all else loves it. So working with him was to force him to draw, to draw for a long time until he reached the four stages of the evolution of this sort of character. And what happened is that he arrived in Berlin with his fabrications that were made of pink latex, huge pieces of pink latex with some kind of very primitive movement since we didn’t have a lot of money to do all of this, so there were no sophisticated electronics, and I must say that I turned into a make-up artist and a painter, because it was essential to do something with it; poor Bruno Nuytten (the cinematographer of Possession) really spent countless hours brainstorming and working on how to solve this.

In fact, we see it four times, as a monster, let’s say; the first three times we had to go over it twice before we understood how to set up this thing, the difference between drawing and making it was so huge! Rambaldi found it absolutely normal; he told me: “You know, the close-up, the famous shot that shows the little guy at the end of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, they shot the close-up over six weeks, they did six weeks of shooting, eight hours a day, they used, I don’t know, 100,000 meters of film to find the angle, the way, the lighting, the thing.” I had eight weeks to shoot the whole film, each day we ran into overtime because this monster was difficult. We were three days over schedule because we had to learn how it worked, and it was three days that I never recovered by the end of the movie. There are two scenes that I never got to shoot in the movie because I didn’t have the three days back, the budget was so tight that I had to shoot day by day exactly what I had to do, it was insane, really, very, very difficult.

C: But you said earlier that you had thought of doing it in Warsaw, and it seems to me that the choice of Berlin and the Wall implies the idea of a No Man’s Land, or at least a back-and-forth between East and West?

AZ: That’s it, yes! That’s exactly why I went to Berlin! Because this film is very far from being a political film, but, you know, any political line meets a morality, it is born out of a morality, and besides, creates a morality, so Berlin is the perfect place to see that, without making “statements” as they say, without making empty, worthless statements.

Special-effects artist Carlo Rambaldi creating the monster for Possession

C: But nothing indicates that the story takes place in 1981, we have the impression that we are after some kind of catastrophe, we don’t really see Berlin, we don’t see any Berliners, we see very few people, the city is basically deserted…

AZ: As a matter of fact, that’s what caused us a lot of problems during the shooting because we shot in a neighbourhood where there is a huge Turkish community. It’s the same neighbourhood where there have been riots these past few days, it’s a neighbourhood that is populated by Turks and young people who are jobless, who have nothing to do, who squat houses because they don’t have a place to live, when they see a film crew that is for them the very illustration of Western decadence, money, while they have an extremely difficult life, they stand in the street, they want to protest, they want to be on the screen and say what they think about it, it’s very difficult… However, I tried to make a city that has a great degree of abstraction because of this emptiness and yet, with these soldiers and this wall, has a degree of concreteness, if you prefer; for me the two combining together could bring the war to an end. Berlin, as it is, cannot bring war, it’s obvious when you’re there, but the essence of the situation in Berlin can bring war, and that’s especially what was photographed, I think. And then this wall is of great simplicity, it’s a city of absolute simplicity, of great simplicity with a capital ‘S’, it’s the kind of thing you don’t do. How do you make a wall? Well, you just make a wall, that’s it, and it’s as simple as that!

C: Is there a part of the production which is American?

AZ: No! I have to say that the producer was very serious about the idea of making a European film, therefore a film that is beyond American control. You know that American control is terrible because the producers have all the rights, the notion of the artist and of the director doesn’t exist if your editing doesn’t satisfy them, well, they bring the film back to you entirely, and as we knew in advance that this film was obviously not going to be commercial, we tried to keep the Americans away. But it’s also obvious that the profitability of a film like this is not going to be achieved, as with Claude Zidi’s films for example, only in France. [Ed: Zidi is a popular director of mainstream French comedies.] You have to know that this film will be seen almost everywhere, and therefore English was the obvious choice. English is nobody’s language and everybody’s language, and knowing that this film would be seen almost everywhere but not just somewhere, you had to choose the Americans who would step in to buy the film and show it, and that’s what’s happening right now.

Translated from French by Sara Sanchez.

This is an excerpt, translated and published with the permission of Serge Toubiana and Pascal Bonitzer, from a forthcoming collection of archival writings relating to Possession edited by Daniel Bird.

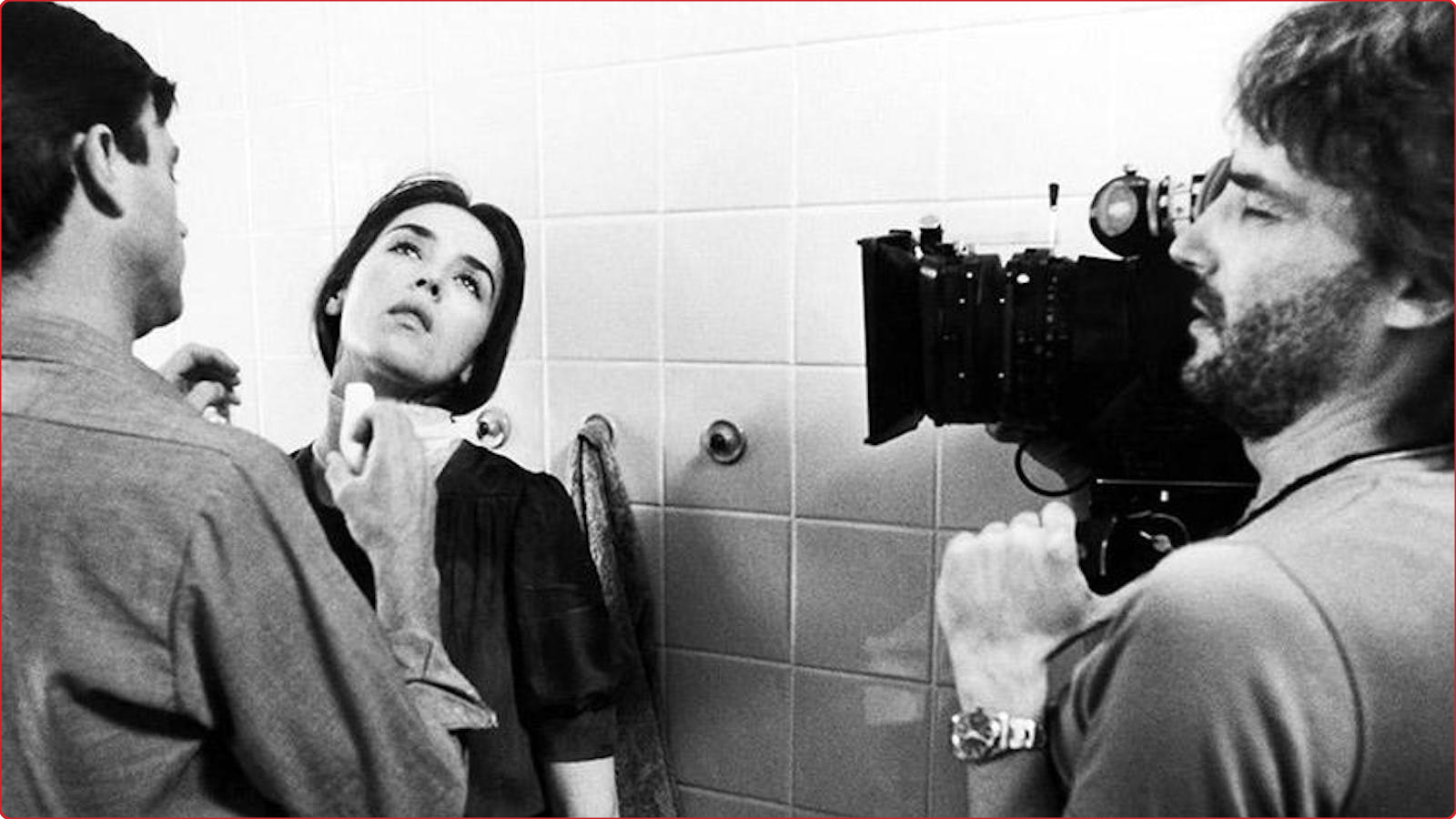

Sam Neill, Isabelle Adjani, and Andrzej Żuławski on the set of Possession