From the Magazine

The Metrograph Interview #1: Clint Eastwood

The first installment of our centerpiece interview series: a rare, career-spanning chat with the legendary actor and filmmaker Clint Eastwood.

Clint Eastwood photograph by Philippe Halsman, 1973 ©Philippe Halsman/Magnum Photos

This interview appears in Issue 1 of The Metrograph, our award-winning print publication. Explore more of Issue 1 and newer editions here.

FOR A COMMERCIAL FILMMAKER TO survive and even thrive in the absence of accolades from both the industry and the intelligentsia is no great feat; many of our finest have managed it. Clint Eastwood, who subsisted through decades of consoling himself with popular success in place of critical acclaim, has accomplished something rather rarer. A household name as an actor before he ever tried his hand as a director, he’s maintained his poise and panache after being stricken with the respectability that comes to ugly buildings, politicians, and genre filmmakers if they last long enough.

At 94, Eastwood has passed through his season of panegyrics at, among other places, the Kennedy Center and the National Film Theatre, and run, with impressive equanimity, a gauntlet of annual awards galas that became routine after his 1992 film Unforgiven took home four Oscars, including Best Director. But if some of Eastwood’s aughts output shows worrisome signs of concession to the Academy and the malign influence of producer Brian Grazer, Eastwood’s films of the last decade, the work of a man who has outlived peak prestige, retain much the same qualities that defined his best directorial efforts from the get-go. These include a demotic directness of emotional expression, a commitment to personal filmmaking within the context of the mass market, and an always present fascination with performance—with the particularities of his own screen presence, with those of his stars, and with the mediated manipulation that crafts the rough clay of flawed human beings into salable messages and burnished archetypes, be the instrument a writer of dime novels like Saul Rubinek’s W. W. Beauchamp in Unforgiven or US government propagandists in 2006’s Flags of Our Fathers. (A line spoken by Adam Beach’s character in the latter film is pertinent: “I can’t take them calling me a hero; all I did was try not to get shot.”)

Eastwood was no overnight success story. He began his career in show business, none too auspiciously, as a day player in lowbrow fare like Francis in the Navy (1955), the sixth film in Universal-International’s “Francis the Talking Mule” series; his breakthrough arrived via the CBS Western Rawhide, in which he punched his meal ticket for eight seasons playing the oft-reckless Rowdy Yates, second-in-command to Eric Fleming’s Gil Favor. Once Rawhide’s long and winding prime-time cattle drive came to an end in 1965, Yates had been briefly promoted to trail boss, and Eastwood had made the leap to leading man—or in Italy, at any rate. Sergio Leone, in the three “Man with No Name” films that he shot with Eastwood as his lead, gave the actor a screen persona that was in some ways the inverse of Yates’s: recalcitrant rather than rash, tactical rather than headstrong, almost Bressonian in his impenetrable opacity, his calm containing coiled danger in its depths—a persona that Eastwood has tinkered with, deconstructed, and whittled down in the years since, but never fully abandoned.

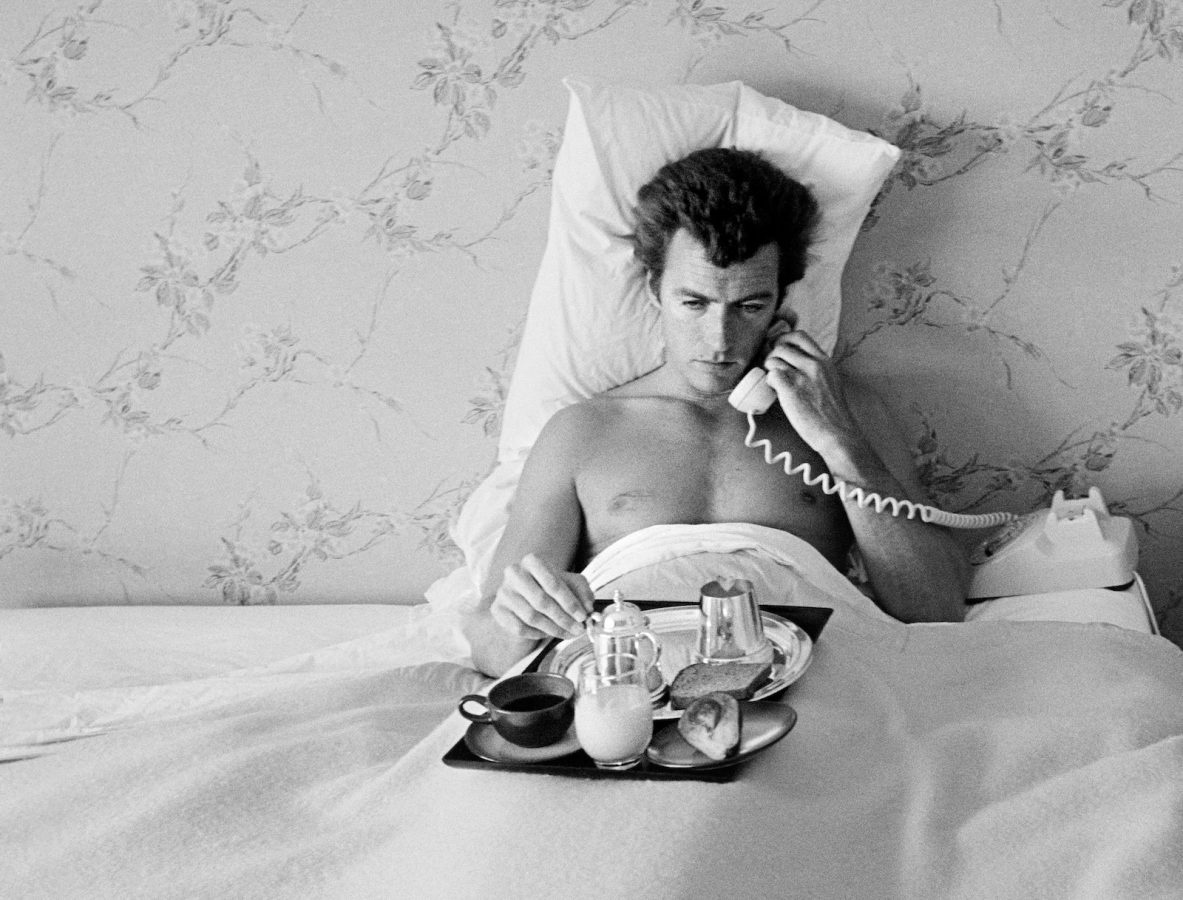

Eastwood breakfasts in bed. North Hollywood, 1958. Photograph by John R. Hamilton. ©Trunk Archive

Released stateside in staggered installments throughout 1967, Leone’s trilogy gave Eastwood a much-heightened profile as well as a sufficient revenue stream to bankroll his own production company, whose issue would raise him to the ranks of screen aristocracy. The Malpaso imprimatur first appeared on the 1968 Ted Post–directed Western Hang ’Em High, graces every Eastwood directorial effort in theaters, up to and including Juror No. 2—his 40th theatrical feature—and is present on his five films with director Don Siegel (1968’s Coogan’s Bluff, 1970’s Two Mules for Sister Sara, 1971’s The Beguiled and Dirty Harry, and 1979’s Escape from Alcatraz), a mentor figure every bit as crucial as Leone.

Eastwood’s debut feature, the thriller Play Misty for Me, shot in his adoptive Northern California hometown of Carmel-by-the-Sea on the Monterey Peninsula, was released in 1971, when its director/star was a callow lad of 41. His six-decade run behind the camera, impressive though it is, is not unprecedented in its longevity. It’s worth remembering that Eastwood started as a filmmaker later, and later in life, than many of the film school–minted “movie brats” whose names we connect with the so-called New Hollywood of the ’70s: Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, for example. That Eastwood has never seemed contemporary to New Hollywood is not a matter of age—he was born five years after Robert Altman, one after Hal Ashby, six before Dennis Hopper—but one of directorial demeanor and, to use a phrase Eastwood almost certainly never has, mise en scène. His Italian sojourn notwithstanding, the various European New Waves seem to have little affected his philosophy of filmmaking, a loose, matter-of-fact approach to blocking scenes, shooting them, and shaping them in the edit that owes much to Siegel and William “Wild Bill” Wellman, whom Eastwood studied closely during his three weeks shooting 1958’s Lafayette Escadrille.

His films are not, as some have proclaimed, bridges to the chaste classicism admired in studio-era Hollywood—neither, for that matter, were the later films of Siegel and Wellman, or Leone’s positively postmodern Westerns—but while dabbling in funky handheld camerawork and occasionally spelaean lighting, Eastwood shows little interest in expressionistic flourish and folderol. To his detractors, Eastwood’s famously brusque, no-nonsense, get-the-shot-and-get-the-crew-home-for-supper comportment suggests a certain laissez-faire laxity; to those of us who admire his films, a precision of vision and a preference for the freshly sprung energy of an early take.

Like Harry Callahan with his .44 Magnum cannon, Eastwood takes very careful aim when he shoots. If the occasions when an Eastwood character strings together enough sentences to give something approaching a monologue are so memorable (“Do I feel lucky?’ Well, do ya, punk?” / “I’ve killed everything that walks or crawls at one time or another” / “I understand you men were just playin’ around but the mule, he just doesn’t get it”), this may be accounted to their relative scarcity, his sibilant hiss being more often employed in issuing curt, clipped, contemptuous one-liners as though he’s sending them in the direction of a spittoon—which, one often senses, particularly in the early films, is just about how highly the Eastwood loner values most of humankind. Nurtured in yesteryear’s Hollywood studio system and still plugging along in today’s, Eastwood has developed an economical approach that has much to teach independent artists of all stripes; to quote the late Steve Albini, “If a record takes more than a week to make, somebody’s fucking up.”

In contrast to coevals like Altman, Ashby, and Hopper who came to prominence as filmmakers after the Summer of Love, Eastwood never suited up in love beads or a Nehru jacket. When he did have occasion to rub shoulders with the counterculture in films, its representatives were generally either insalubrious or plain ridiculous, like the ruthless acid casualty Don Stroud and the drippy hippies of Coogan’s Bluff or Andy Robinson’s scruffy Manson/Zodiac Killer amalgam in Dirty Harry. (A notable exception is Kay Lenz’s freewheeling flower child in 1973’s Breezy, breathing life back into a morose, middle-aged William Holden.) Eastwood’s association with Harry—and, by the reasoning of some cultural commentators, with the forces of conservative law and order—has continued to color certain critical responses to his work.

One of Eastwood’s most relentless detractors, Pauline Kael, described Dirty Harry as “a kind of hardhat The Fountainhead.” What was being inferred by the allusion to the 1970 Hard Hat Riot in Lower Manhattan, a punch-up between student protesters, American flag–waving construction workers, and lunch-breaking Wall Street traders, would’ve been immediately clear to a New Yorker reader of the day. Eastwood, implicitly, was a reactionary firmly on the side of the country’s hairy-shouldered, Miller High Life–swilling, Nixon-voting “love it or leave it” Archie Bunker troglodytes, Harry a cinematic analogue to Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” and “The Fightin’ Side of Me.”

Eastwood did little to disabuse his detractors of these notions—in fact he dueted with Haggard on “Bar Room Buddies,” recorded for the soundtrack of his 1980 Bronco Billy—but his films complicate such readings. Harry is less a prescriptive picture than a descriptive one; per David Thomson, a “tortured vision of conservative ideals at breaking point.” The biographer Richard Schickel recalled that “Clint has always said he found something sad about Harry”—and in an age when overeager-to-please Joss Whedonian wisecracking through clenched grins is endemic to the action blockbuster, the anguish at the heart of so many Eastwood performances is all the more striking; it’s inscribed in the trench-like furrows that converge over the bridge of his nose, which suggest someone who has been suffering from a stress headache for several decades.

The process of Eastwood’s “demythologizing” his image of monumental, imperturbable machismo, which mainstream critics sat up and took note of around the time he fumbled his way into the saddle in Unforgiven—or, at earliest, with his John Huston impersonation in White Hunter Black Heart (1990), a thinly disguised retelling of the troubled location shoot for The African Queen (1951) in British Uganda and the Belgian Congo—was already underway in the fledgling days of Malpaso. In Misty and The Beguiled, his characters’ cocksure alpha male composure is either sorely rattled or obliterated entirely by the force of feminine rage, and in Sudden Impact (1983), significantly the only Harry Callahan film that Eastwood carries a director’s credit for, Harry meets his match in the person of a vengeance-driven Sondra Locke, Eastwood’s frequent co-star and romantic partner of more than a decade. (In the following year’s Tightrope, a pungently sordid detective thriller putatively directed by one Richard Tuggle, Eastwood’s New Orleans detective is something like a Callahan beset by sexual neurosis, compulsion, and dysfunction.)

Trying to fence Eastwood and his work on one side of the American ideological divide proves a tricky task. Running through his filmography, it’s true, one finds a consistent streak of criticism of federal government and law enforcement—FBI goons including Bradley Whitford’s itchy-fingered sharpshooter in A Perfect World (1993) and an exploitative Jon Hamm in Richard Jewell (2019), the Secret Service and the upper echelons of the executive branch in Absolute Power (1997), the meddling, know-nothing National Transportation Safety Board representative in Sully (2016)—a tendency that reaches something like its apotheosis in 2011’s J. Edgar, a biopic of the Bureau’s first director that describes how its subject’s terror of the discovery of his own private peccadilloes led to his relentless cataloguing of the secret lives of others. By comparison, representatives of state and local government, like Eastwood’s Texas Ranger in A Perfect World, are comparatively benevolent, and most reckonings record Eastwood’s two-year stint as the nonpartisan mayor of Carmel-by-the-Sea as a peaceful reign, during which his civic acts included the overturn of a draconian ice cream cone ban.

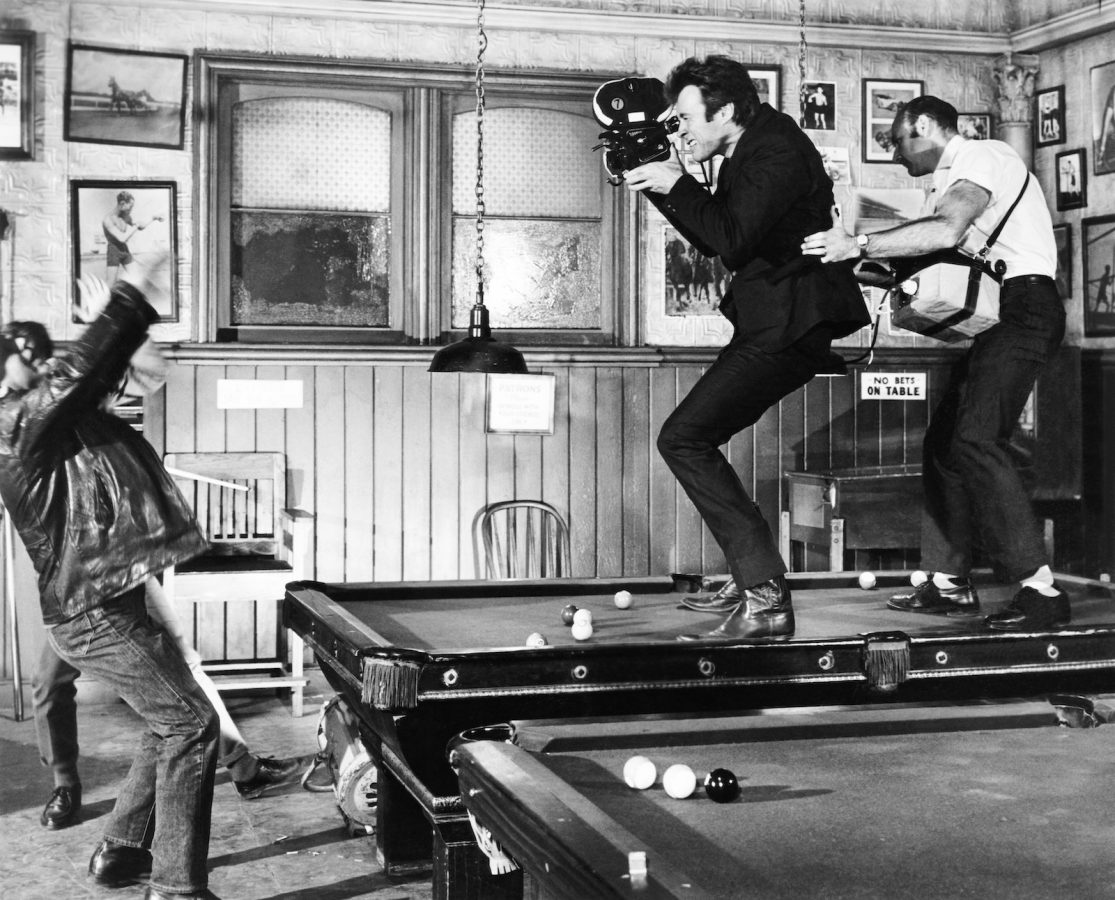

Eastwoodon the set of Don Siegel’s Two Mules For Sister Sara (1970).

If having a somewhat skeptical view of American federal agencies is intrinsically “right-wing,” however, most of the country today would qualify as candidates for membership in the John Birch Society. There are those who will, of course, point to Eastwood’s infamous appearance at the 2012 Republican National Convention as evidence of a paleoconservative agenda in his work, and insist that his 2014 American Sniper is pure propaganda, but it’s conveniently forgotten that Eastwood grilled empty-chair Obama on the RNC stage about ongoing US military involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan. To all appearances the rise of Donald J. Trump has left the libertarian-leaning Eastwood unmoved. In 2016, he likened the president-to-be and his opponent Hillary Clinton to Abbott and Costello; in 2020, signaled a preference for the turtle-lipped, undeniably efficient Democratic-nomination hopeful Michael Bloomberg; and has remained aloof of the fray since. (The lack of affinity may be temperamental above all else; it is hard to imagine a figure more diametrically opposed to the laconic, prototypically Western brand of masculinity represented by Eastwood than the braggadocious, verbally diarrheic New Yorker.)

Lean-hipped, a looming 6’4″ in his prime, and with a dusky pompadour adding a couple of extra inches, Eastwood has a genetic ticket punched to play the unflappable US Übermensch, but in the director’s chair he is far from embodying the second coming of the actor-cum-director whom he unseated from the summit of the Motion Picture Herald’s “Top Ten Money Making Stars” list in 1972: John Wayne. Unlike Wayne, who loaded his The Green Berets (1968) with beefy middle-aged bull session pals, Eastwood tends to travel alone; his filmography is filled with men cocooned in their own misanthropy, and in Pale Rider (1985) he portrays an actual revenant, removed from the world of mere mortals he’s returned to brutally admonish. When he does condescend to take on company, it’s of a more motley sort, including the ragtag Civil War–era outcasts of The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), the Wild West show troupe of Bronco Billy, the gaggle of geriatric astronauts of Space Cowboys (2000), and quite a number of distinctive leading ladies—Locke, Verna Bloom, Jessica Walter, Marsha Mason, Hilary Swank—in parts that transcend the window-dressing roles that women are often consigned to in American action films. One can imagine a Wayne of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) vintage being ruefully effective in a full-bodied melodrama like The Bridges of Madison County (1995); it is rather more difficult to imagine him selecting such material to direct himself. Far from being a safe, stay-in-his-lane action specialist, Eastwood has built a filmography distinguished by its disarming eclecticism, encompassing male menopause weepies (Breezy), musicals (1982’s Honkytonk Man), biopics (J. Edgar), musical biopics (1988’s Bird, 2014’s Jersey Boys), sporting dramas (2004’s Million Dollar Baby), sporting drama biopics (2009’s Invictus), one docufiction experiment that’s something like a 21st-century Louis de Rochemont production (2018’s The 15:17 to Paris), and… whatever you want to call Hereafter (2010).

There are, to be sure, an arsenal of more traditional he-men scattered throughout Eastwood’s filmography: his imperially arrogant art historian/alpinist Dr. Jonathan Hemlock in The Eiger Sanction (1975), his CDL-certified bare-knuckle brawler in the man-and-his-orangutan diptych Every Which Way But Loose (James Fargo, 1978) and Any Which Way You Can (Buddy Van Horn, 1980), his haughty half-Russian air force major in Firefox (1982), his yoked-up, stogie-chewing Marine Corps gunnery sergeant in Heartbreak Ridge (1986), his LAPD supercop in The Rookie (1990). In the last-named film, an immobilized Eastwood is raped by Sônia Braga, the apex of the series of onscreen paybacks that he’s endured in return for his sexual brigandry since the days of Misty and The Beguiled, and one of many instances of the eccentric, off-color humor that individuates Eastwood’s two-fisted popcorn movies from those of, say, the terminally self-serious Chuck Norris. If what Eastwood learned from Siegel was a certain clarity of vision—how to, in his own words, “know what you want to shoot and to know what you’re seeing when you see it”—the abovementioned action spectacles suggest he took a different lesson from Leone; like the Italian maestro, he developed a proclivity for inflating the tropes of the action film until they reach dizzying heights of heterosexual camp.

Eastwood’s last three films as actor/director—Gran Torino (2008), The Mule (2018), and Cry Macho (2021)—all find him playing variations of the same role, that of a leathern, crusty, slur-spouting child of the Depression who’s grown wholly alienated from the world of the affluent white middle class around him, finding new purpose in contact with Hmong immigrants, cartel gangbangers, and cantina-owning señoritas, respectively. In these elegiac works, Eastwood, always acutely and ironically aware of his increasingly weatherworn iconic image, depicts himself as handing the keys over—in the case of Gran Torino quite literally—to younger generations, to those who will persist after he’s gone.

Some, it seems, are eager to hasten his departure, even within the industry for which he’s earned the annual GDP of a small nation throughout the years. A 2022 report has the Warner Bros. CEO David Zaslav haranguing executives over the greenlighting of Cry Macho out of deference to the filmmaker’s long, lucrative association with the studio, in spite of their stated skepticism over its potential profitability, reminding them: “It’s not show friends, it’s show business.” The quote comes from Cameron Crowe’s 1996 Jerry Maguire, which gives some sense of the cultural horizons in the morass that passes for Mr. Zaslav’s mind.

But Eastwood, unlike Mr. Crowe, has never languished a day in “director jail.” This is remarkable in itself because the commercial moviemaking that we metonymically persist in referring to as “Hollywood” is a game that the house almost invariably wins, and almost all who play find themselves involuntarily retired, if they don’t have the good grace to die first. Prior to its release, an unsubstantiated rumor made the rounds that Eastwood’s Juror #2 (2024) will be his last film. If this should indeed prove to be the case, it’s a safe bet that Eastwood and Eastwood alone decided it would be so. If his latter-day directorial efforts gained the respect of the chattering classes for their address of knotty moral dilemmas, the appeal of his professional endurance in the face of stacked odds is rather more simplistic, and easy to articulate in layman’s terms: sometimes you just want to see a guy beat the bastards. —Nick Pinkerton

Eastwood and Meryl Streep by one of the eponymous Bridges of Madison County (1995).

NICK PINKERTON: Mr. Eastwood. How are you?

CLINT EASTWOOD: Not too bad, how about yourself?

NP: Oh, I can’t complain. Thanks for taking the time to speak with me.

CE: No problem. We’re just sitting here with two dogs.

NP: I won’t take too much of your time up. I’m a great admirer of the body of work, and I’d like to ask some questions about the career as a whole, if I may.

CE: Sure, go ahead. I don’t know if I’ll have the answer…

NP: I suspect you’ll have a thing or two to say. I want to start with Sergio Leone, the figure who, more than any other, oversaw your transition from television to film acting. What were some of the essential lessons that Leone gave you in becoming a big-screen actor, in shaping your screen persona?

CE: You know, I don’t know, because acting is acting as far as I’m concerned. I was doing a television series when [Leone’s people] called my agency. At first, I said, “I don’t think so.” Then when I read the material I realized that it was [a retelling of] Yojimbo (1961). Some years earlier, when I was in LA, a theater ran a lot of foreign films. I had gone one night and watched Yojimbo; hadn’t known anything about it, though I did like the director, Kurosawa, so I thought it couldn’t be that bad. And it was really good. I said to a buddy of mine, “This is amazing, this thing would have been a great Western.” And that was the end of the conversation. Then some years later, all of a sudden, here I am getting asked to make a Western out of Yojimbo. A lot of irony going on. So my agency in Los Angeles called the Rome office and said I’d read the material; I read it, I liked it, and I went over [to Italy] and met Sergio. He didn’t speak a word of English. And I didn’t speak a word of Italian. I just said, “Buona sera,” or something like that. But we had a lovely lady who spoke about six languages who interpreted. That’s the way we shot the picture. He’d say, “Tell Clint to just walk over here and do the scene.” That was it. Toward the end, after our third picture, he spoke a few words of English, and I spoke a few more words of Italian. And that’s about as exciting as it gets.

NP: You say acting is acting… You’d certainly had success on Rawhide, but the Leone films [1964’s A Fistful of Dollars; 1965’s For a Few Dollars More; 1966’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly] made you into an iconic figure, a bona fide star. And there are certain things about the performance style in those films that carried over to how you conducted yourself onscreen afterward: the taciturnity, the long silences, the thoughtful minimalism…

CE: Yeah, that was all there in Yojimbo, written in by whoever wrote that story in Japan. I didn’t know Sergio at the time, he’d only done one picture as a director, The Colossus of Rhodes (1961), but he was an assistant director on a lot of pictures. So he’d had a lot of experience in the business—the Italian business, which is a bit different than ours.

NP: Along with Sergio Leone, the other figure you’ve pointed to as a crucial mentor is Don Siegel.

CE: Don was a good guy. He’d been at Warner Bros. for years.

NP: Head of the montage department, for starters.

CE: Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) was his most famous film at the time we started working together. And it was one of the great B-movies, if you want to call it that, of all time. Don was different from Sergio in that we were speaking the same language and so we communicated better. But Sergio and Don both liked some of the same kind of material. And Don basically emulated, or was inspired by, the kinds of pictures we all liked, and they eventually caught on—not only in Italy but in every country that they played.

NP: At what point did you start thinking about directing yourself?

CE: It started out during Rawhide. They had let [Rawhide co-star] Eric Fleming write a story. I said, “You know, I don’t want to write a story, but I’d love to direct one of the episodes.” And everybody, everybody at CBS, said yes. Around the same time, some other series let one of the actors direct an episode. Evidently, they went way, way over budget; way, way over schedule. It turned out not so well. So upstairs sent an edict saying: “No more actors are to direct.”

The thing about doing a television series is we had different actors and different directors every week. Many would circle back around, but we worked with a lot of different people. So you’d get an idea of what they were trying to do and what you’d like to do if you were doing it yourself. You’d get to thinking: “I like what he’s doing; I don’t like what he’s doing.” I paid attention. Then, when your turn comes up, you have a vision in mind, and you lay it down the way you want. It either works out or doesn’t.

Eastwood and director Don Siegel look out on the rooftops of San Francisco, in Dirty Harry (1971).

NP: Were there any actors-turned-directors or actors-turned-producers who you thought had done it the right way? I’m thinking about people like Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster, who started their own production companies. Was there any model you aspired to?

CE: No, I don’t think so. I mean, there probably was, but if so, it was subconscious.

NP: You’re known to keep a pretty quiet, hushed, relaxed set, to maintain a very brisk shooting schedule, to avoid excessive retakes, excessive coverage. Were these priorities from the beginning, or was there a trial and error period around the time that you started directing yourself?

CE: Oh, you get different ideas about things as you go along. I liked the sets that weren’t too noisy. And a lot of the Italian sets were noisy because they didn’t record direct sound—well, they recorded it, but then they’d re-record everything later on because the sound wasn’t any good, so the sets were more talkative. American sets were quieter because we’d be recording the sound as we go.

NP: When you founded your production company, Malpaso Productions, in 1967, I have to imagine you were already looking toward directing… What about the script for Play Misty for Me made it the project you felt you wanted to start your directing career with? It’s very different from anything else you’d done to that point.

CE: Well, I had this friend, a lady friend, Jo Heims, who was a production secretary [at Universal]. We used to sit and drink beer together in Hollywood, and she was always saying, “I want to write movies.” I never thought too much about that, we’d just have a few beers. One day she came in and she had this story called Play Misty for Me [co-written by Dean Riesner]. It was written to be done somewhere in Los Angeles; I thought, “No, this would be great in a small town.”Because in a small town, disc jockeys are a big deal. A lot of them become interesting people in their communities. I said: “This would be great in the community I live in in my spare time, Carmel in Monterey County.” So I picked all the locations in Monterey County and made the movie.

From there, I just kept going. I did one called Breezy by the same writer, Jo Heims. I didn’t want to play in that, so I got William Holden; I thought it would be a great opportunity to get a lot of experience and work with somebody I really like. Jo had given me the material because she thought I could play it, but I thought it needed somebody a little older than me. Fortunately, Holden liked it. I guess he liked having a teenage girlfriend. It was a very different story from Play Misty for Me. I just kept trying different things all the time. Once in a while they’d work.

NP: You tend to have long working relationships with certain key personnel, particularly cinematographers, starting with Bruce Surtees, who you worked with on and off from Play Misty for Me through to Pale Rider (1985). What is it that you look for in a DP?

CE: I liked Bruce because he was fearless. He would try anything. And if we wanted to do something unusual when we were shooting, he’d go along with it. He would try things that were different, without batting an eye. We used to call him the Prince of Darkness because he wouldn’t use much light. We’d do a night scene, and he’d have a little flashlight. He’d use low light very well; sometimes he’d get away with it, sometimes it didn’t work. But he wasn’t afraid to be experimental, and I wasn’t either. So that worked out pretty good. He did a lot of pictures for me.

NP: How about Jack N. Green, who you first worked with on Heartbreak Ridge?

CE: He was excellent. He was from the same group, the same mindset. We were all from the same group, all experimental.

NP: Would you say a willingness to shoot from the hip was the common bond?

CE: Yeah, I’d say so. Or to just take careful aim.

NP: Tom Stern? He took up the reins on Blood Work (2002)…

CE: Tom worked his way up. He worked with Bruce [as a gaffer on Honkytonk Man through to Space Cowboys].

NP: There’s a lineage, yes. It took a while for highbrow critics in the United States to warm to you and your films, with a few exceptions: Dave Kehr, Tom Allen in The Village Voice. But early on you had an ally in France in the person of Pierre Rissient, who I got to know at the end of his life, and Olivier Assayas, I know, was very active in promoting your work as a critic for Cahiers du Cinéma…

CE: I think Pierre was interviewing me for something when we met. He got me interested in what the French audiences liked in feature films, and it was interesting, a little different. Pierre liked Don’s films a lot; they were friends. Pierre was interesting because he was extremely knowledgeable about film. You know, French audiences looked at film much differently than those in America did. Americans would go to a film to be entertained. French audiences would study a film, and whether it’s pseudo or otherwise, eventually, it’s intellectualized. It was [for them] a necessary way to look at film, French audiences scrutinized a bit more. A lot of times American audiences go to a film, and they’d either like it or they wouldn’t; they’d come out: “Oh, that was good.” The French would come out and talk about a movie for days. They’d try to figure out what the director was thinking, beyond just putting down words.

NP: When you were first getting Malpaso off the ground, were there any factors that influenced your decision to either take on a script as director or hand it off to someone else? For example, why did Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974) go to Michael Cimino, who had never directed a feature before?

CE: I just wanted to do certain films myself. It wasn’t that anybody else couldn’t do them better or as well. With Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, Cimino wrote the story. Before that, he had directed some small items, and he wanted to direct it—he wouldn’t sell it to me otherwise. I liked the material, and he seemed to know what he was doing, so he made it. Or rather we all made it. But he was the commander-in-chief.

NP: How about the Malpaso films that were directed by James Fargo or [longtime stunt double] Buddy Van Horn?

CE: Well, those were guys who worked for me who wanted a shot at directing. So we did that. I rewarded people for doing good work. They did good work, they had imagination, or I thought they did, and I thought I’d give them a break.

NP: Moving into the ’80s, a pattern emerges where you’re continuing to make genre films, action films—Firefox, Sudden Impact, Pale Rider, The Rookie—that seem to be pitched to your established core audience. But you’re also starting to mix in projects that are a little outside of your wheelhouse: Bronco Billy, Honkytonk Man, Bird, White Hunter Black Heart. Did you think about this at the time as a “one for them, one for me” strategy? A way of gradually adjusting audience expectations? Or were some of these projects more personal than others?

CE: No, I don’t think I intellectualized it at all, I just liked the material. And if I thought it was good material, if I wanted to act in it, if it was something I thought I wanted to make, selfishly, in my own way, I’d approach it from that angle. It would just depend on the mood and the material and the people we had, etc., etc. You want to make sure you give all the actors the break they deserve, to do the best they can.

NP: You work at a very brisk, prolific pace, so the breaks between films you’ve directed are noteworthy. There are three years between The Gauntlet (1977) and Bronco Billy, a little time off between Heartbreak Ridge and Bird. Were either of these, Bronco Billy or Bird, especially difficult films to get made?

CE: As you get a few films that are reasonably successful, people kind of stick with you. But if you’re grinding out turkeys, they don’t stick with you.

Eastwood on the set of Don Siegel’s Coogan’s Bluff (1968).

NP: So the pauses are mostly a matter of waiting for the right material to come along?

CE: Yeah. It’s not an intellectual sport, it’s an emotional craft. Sometimes you like a script and want to do it as an actor; sometimes you like a script because you think you’d also want to direct. You get a feeling about certain projects and you want to make sure you get your stamp on them, because if you turn them over to somebody else, they might start seeing things differently… If you have somebody directing who doesn’t see the material, it’s not much fun. If you’re with a director like Sergio or Don, that makes it fun. It makes it come out like you hoped it would come out. If you do it yourself and it’s bad, you take the beating; if it’s okay, you get the glory.

NP: You used the term “experimentation” earlier when talking about wanting to always try new things. Is that part of your process when selecting projects: looking for ways not to repeat yourself?

CE: Yeah, I think so. If you think about it hard enough, you look at every project differently. If it doesn’t give you enough to think about, you move on to another thing.

NP: Jersey Boys was the first Malpaso musical since Paint Your Wagon (1969), and the first musical, in the traditional sense, that you’ve directed. Is there any genre, any kind of film, you haven’t yet tried that you’d like to take on?

CE: Well, there probably is, but I wouldn’t know until I saw it. I’ve tried quite a few things over the years. If they were new things at the time, I don’t really remember thinking about that aspect. Because, again, I think it’s an emotional rather than intellectual artform. It’s intellectual in the sense that you have to keep it organized in your mind, and there’s a technical aspect to it that has to be worked out. By the same token, this is all toward getting the emotional responses that you want a film to have, getting the thing to come out the way you like, in such a way that you’re happy with it. You go in with a certain idea. If it comes out the way you thought, or if other people see it your way, that’s fine. If they don’t, that’s fine, too. But if it’s not what you intended, if it doesn’t come off… back to the drawing board.

NP: Are there any films of yours which you don’t think got the response they deserved?

CE: Maybe? I don’t know, I’ve never thought about it that way. If I’m happy with it, that’s it. As far as if anybody else has a different feeling about it, well, that’s theirs. I’m sure I’ve had disappointments. If I did, I wouldn’t dwell on them.

NP: Did your experience of directing change your approach as an actor working for other directors? Knowing the particular needs or insecurities that actors have, but also having the duties and responsibilities of a director… How do you balance that conflict, if it is a conflict?

CE: I don’t think it’s a conflict. I remember when I hired Don Siegel to play a small bit part in Play Misty for Me, he said, “You’re making a mistake, you should never hire me, you should hire an actor.” I said, “Oh, come on, you’ve worked with actors all these years, just do this little part.” And he kind of enjoyed it.

All those things you mentioned are emotional matters. You have to deal with all of them. You have to make the set and the material as comfortable for the performers as you can in order to make them do the best they can. So, if you’re a loud-mouth director, come to set,start chewing people out—which I’ve seen before, I’ve seen those kinds of sets—you’re not going to get the same performance, you’re not going to get the very best that they can give you. Unless maybe you want them to feel uncomfortable. Depends on what you’re looking for. The best part about working with actors is I like actors; I was one myself, and so I like them. It’s fun to see actors doing well in a project and giving you what you want.

NP: Would you say a large part of the job is just creating an atmosphere that’s conducive to actors doing their best work?

CE: I think that’s the largest part of the job.

NP: One of the things that is increasingly distinct about your pictures is your commitment to naturalism, particularly in your location shooting and production design. The working-class South Boston row houses in Mystic River (2003), run-down Detroit in Gran Torino, the lower-middle-class Atlanta apartments in Richard Jewell… we don’t see unprettified spaces like these, which show the texture of contemporary American life, very often at the multiplex these days.

CE: You could make those pictures in different areas; I could have not gone to Boston, could have gone somewhere else. I’ve tried to duplicate settings, but what’s better than going to the real place to deal with the real people who live there? Real backgrounds, real cars, real everything. It just makes it easy. I try to do the same with people, too, sometimes; get them doing things they’ve really done in life. It’s more fun to relive the story than trying to compensate for something that isn’t there—though if you’re doing a period piece then, of course, you have to rebuild things.

NP: I’d be interested to hear you talk about your casting of nonprofessionals in key roles, something you did in both Gran Torino and The 15:17 to Paris, which is a radical act we don’t see often in mainstream movies.

CE: Well, in the particular case of The 15:17 to Paris, that was a real event, and I wanted them to re-create it as it happened. I had to go over it quite a bit to get the feeling. It started out as a documentary, and it was fun using the actors who’d actually been through it to re-enact the scenes. I didn’t know if I’d be able to get them to feel the same things, the same fears that they went through. When you’re on a train and things are looking bad, how do you handle it? I thought it’d be interesting to do. They were very close to the ages they were when the events [depicted] in the film happened and I wanted to capture the atmosphere.

NP: The casting almost reflects the circumstances of the event: these ordinary guys who stepped up to do something extraordinary are now guys who are not trained as film actors stepping up to carry a film.

CE: Yeah, exactly.

Eastwood checks out the framing of a shot of Absolute Power (1997) in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

NP: You’ve kept up a uniquely long-lived rapport with your audience through the years. The Mule, for example, is a small movie that’s almost totally based around just your screen presence, and that presence alone sells it—or at least your name is the big one on the poster. Gran Torino is even more reliant on your star power. As we know, Hollywood likes to get rid of people as soon as they’re not useful, but you’ve singularly managed to survive. Are there any particular factors that you think have played into this?

CE: Oh, I don’t know. That would be up to them, to the audiences, to answer. Up to the people on the outside. I just kind of go along. I consider this, again, emotional. It comes upon you. You have a story, you make a movie of it. You have to just go for it. If you think too much about how it happened you might ruin it. I go back and look at films I’ve made, and I could ask easily, “Why the heck did I make this?” I don’t remember! It might have been a long time ago…

When I did that picture you’re talking about, The Mule, I liked the script, but I had no idea of starring in it. I thought, “That’s just something I’ll direct.” My gal in the office said, “You’ve got to play it.” I said, “You’re kidding.” I just thought it was a good script and an interesting project. Sometimes you have to listen to what’s going on around you. Good idea. Why not?

NP: I know you’re a great admirer of jazz music, which pops up in some of the films: Bird, of course, but also Johnny Otis and Cannonball Adderley at the Monterey Jazz Festival in Play Misty for Me, which gets its name from an Erroll Garner composition, your piano noodling in In the Line of Fire (1993)… Has that in any way influenced how you think about your creative process?

CE: Well, it’s an artform that is about creating as you go to some degree, so maybe there’s a little correlation. But probably not. I like jazz because it’s constantly looking at everything from different angles.

NP: Having spent so much time in the film industry, where do you feel the business is now?

NP: I don’t know where it is now. It is where it is. I’m not an expert. I just know what sounds good at the time. And that’s a good story.

I remember reading a review of Mystic River in a magazine and calling up the author of the book [Dennis Lehane] and purchasing [the rights] right there. Not the book—a review of the book. I just loved what story you could get from the review. I called my agents and said, “I need this story.” I did ask my agent to get me a copy of this book, and it was just as good as I thought it would be. They all come from different places. I could have thought about it another day or two, or if I was at another point in my life, I could have thought, “Who needs that?” But at this point in my life, it was exciting. Suddenly, you feel it. Keep it simple.

That’s the difference between emotionalizing and intellectualizing. Sometimes you can talk your way into something; sometimes you can talk your way out of something.

NP: Before we go, Mr. Eastwood, I must tell you, you were my late grandmother’s favorite actor. Mary Lohman of Indianapolis, Indiana. And she would be so thrilled to know that this phone call occurred.

CE: I’m very happy that she would have felt that way.

Share: