Columns

Listen up! Elvis Presley’s Flaming Star

Metrograph’s Listen Up! column, in which we revisit movie scores and soundtracks of note, takes a momentary detour to look at the (El)vicissitudes of making the King’s best movie—and Don Siegel’s best Western—Flaming Star (1960).

Flaming Star plays at Metrograph from Saturday, October 11 as part of Don Siegel: Last of the Independents.

Share:

IN THE FALL OF I958, while private Elvis Presley guarded the Fulda Gap against the Soviets with the Third Armored Division in West Germany, his manager Colonel Tom Parker took full advantage of his client’s conscription-mandated absence from stages and screens large and small, to solidify the advantageous position they both hoped to occupy when Presley returned to civilian life. His contractual symbiosis with his record label and music publishers would remain as the Colonel had already lucratively arranged. But Parker harbored a fierce determination to bring Hollywood to tighter contractual heel.

Presley’s initial big screen outings—one for 20th Century Fox, one for MGM, and two for producer impresario Hal Wallis and Paramount—generated nearly exponentially increasing box office grosses. As Presley earned marksmanship badges, began his lifelong study of karate, and courted girls and women to varying degrees of intimacy abroad, Parker, a veteran studio negotiator going back to his days representing country crooner Eddy Arnold’s far less ambitious Tinseltown expansion, relentlessly hammered out a contract calling for four more Elvis films. Each promised generous backend profit shares, rewarding merchandising opportunities, and comfortably covered Presley’s (and screen credited “technical advisor” Parker’s) princely overhead expenses during production and promotion. And each film would also be ready to go before the cameras in swift succession when Presley arrived home in 1960.

The movies occupied Presley’s mind as least as much as the threads of American music he wove into chart triumphs. He was a constant filmgoer throughout childhood and into adolescence, identifying strongly with the outsiders and misfit characters who were energizing much of postwar mainstream Hollywood cinema at the same time as electrified instruments and R&B tempos were simultaneously goosing American popular music. Presley’s iconic pompadour was inspired by young matinee idol Tony Curtis’s hairstyle. He watched James Dean’s and Marlon Brando’s pictures over and over, soaking up their performing essences just as he’d musically fed on gospel quartets and blues balladeers. Well before fame came calling, the Elvis persona, it seemed, had struck his peers as a kind of screen role. “The way he carried himself,” recalled a Humes High School classmate in Peter Guralnick’s peerless two-volume biography of the King, “it almost looked like as if he was getting ready to draw a gun, he would kind of spin around like a gunfighter. It was weird.”

Ironically, the movie genre Presley had the least interest in was the one that Wallis, who initially brought the King to Hollywood, saw as Presley’s best fit. Musicals and their convention of “people bursting into song at the drop of a hat just when things were getting serious,” were, according to back-home girlfriend June Juanico, among his least favorite films. While not contractually stipulated, the understanding was that two of the four pending post army service pictures would let Presley exercise his lifelong desire to front a “serious” movie. Though itself larded with songs, 1958’s King Creole, his final release before reporting for duty, had taken a step in the right direction. Under Michael Curtiz’s heavily Hungarian-accented supervision, Presley negotiated the New Orleans–set coming of age melodrama at well above the level of verisimilitude that Harold Robbins’s source material demanded, while obligatorily delivering the fan-pleasing goods in nearly a dozen musical numbers, and holding his own among a support cast that included Mercury Players and Actors Studio vets, despite having no formal acting training of his own. “He asked so many questions,” co-star Carolyn Jones said of the shoot, a sure sign of an actor seeking the fullest possible inhabiting of his character. “He knew what tomorrow’s work was going to be,” offered the first AD on Presley’s prior film, Jailhouse Rock (1957). Four movies in, he was a pro. “I think,” Colonel Parker said in a contemporary press interview, “Elvis Presley could play any role he makes up his mind to play.”

Flaming Star (1960)

The first of the post army quartet of films to actually shoot would, alas, set the tone for the decade’s worth of largely dismal to outright embarrassing movies shortly to come. G.I. Blues (1960) was Presley’s first of nine films made with Norman Taurog, a director who once extracted on-camera tears from preteen Jackie Cooper by persuading the young actor that his dog had been shot and killed by a studio guard at Taurog’s instruction. It was also the first of a mind-numbing run of modern-dress Elvis roles that Alan Weiss, screenwriter of six other Elvis stinkers, described as, “a loner who appreciated women—preferably in quantity—but whose underlying attitude was audacious and arrogant, even a little contemptuous.” The bulk of Presley’s to-formula filmography contains a gallery of those nearly interchangeable agreeable singing toxic bachelors (at least three of them race-car drivers) all eventually catapulted to the altar by interchangeable ardent but forgiving love interests.

“Presley’s good films,” wrote Micheal Weldon in his Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, “had good directors.” Apologies to Phil Karlson, Gordon Douglas, and George Sidney (helmers of 1962’s Kid Galahad, Follow That Dream, and 1964’s Viva Las Vegas, respectively) but for my money Presley’s two best movies—King Creole and his sixth feature, 1960’s Flaming Star, were the work of his two best directors—Curtiz and Don Siegel. By 1960, Siegel had amassed the kind of peripatetic biography that the seventh art demanded. A table-tennis champ and RADA-trained actor turned nepo baby studio hire (his uncle was a Warner Bros staff producer), Siegel evolved a brilliant command of concise narrative film syntax and editorial shorthand via apprenticeship in Warner’s insert and montage department. It was Siegel, credited with “montages,” whose brief film within the film cinematically sells the historically and geographically preposterous concept of a European refugee trail leading to Morrocco at the outset of WWII that sets up Curtiz’s Casablanca (1942).

Siegel’s subsequent longform directing career evinced a vigorous and precise eye for human asperity and violent conflict, and a sympathetic way with actors of varied experience. I confess I’ve never seen the film Siegel made just prior to Flaming Star, 1959’s Hound Dog Man. The only person I know who has did so at the Cinémathèque in Paris where, reportedly, the full house present remained raptly silent for the entire film only to burst out laughing en masse as the lights came up. It is nevertheless Siegel protégé Sam Peckinpah’s favorite of his mentor’s films, and, by my friend’s accounting, Siegel’s efforts made its teen star Fabian fleetingly seem like he possessed sufficient charisma to carry a movie. Hound Dog Man was, in fact, so unashamedly initiated as an Elvis movie substitute that Fabian wears the exact wardrobe Presley was assigned in Love Me Tender (1958), his screen debut. In any case, its relative success moved Siegel to the top of the shortlist to direct Presley’s second post army movie, the Western Flaming Star.

Prior to Presley signing on, Flaming Star (based on a novel entitled Flaming Lance by prolific Western scribe Clair Huffaker) had spent months in development as a vehicle for Marlon Brando adapted, and to be directed, by Fox A-list screenwriter Nunnally Johnson. But Johnson had lately soured on end-stage studio filmmaking as practiced at Fox. A leadership vacuum left by recently departed Darryl F. Zanuck had been filled by financier Spyros Skouras, a man lacking virtually any of Zanuck’s substantial creative gifts and graces. And Brando’s commitment-phobic handlers led Fox on such an unmerry chase that shepherding Flaming Star (or Flaming Lance or Brothers Of Flaming Lance or Flaming Arrow or Brothers Of Flaming Arrow depending on the title-happy changes of heart Skouras mistook for studio captaincy) had left Johnson, recently decamped to Europe, confiding to a friend that he wished he’d “never been born.”

Besides the paycheck and the opportunity to use his gunfighter moves, Presley was likely attracted to the project by a reunion with producer David Weisbart, who had eased Presley into his first and most thanklessly grafted-on screen role in Love Me Tender. Weisbart could do little wrong in Presley’s eyes as producer of Nick Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1955), a movie the King admired so much he gave it a nickname, an honor largely reserved for girlfriends and entourage members: “Rebel Without a Pebble.” (The fact that Weisbart had also edited Brando’s 1951 debut, A Streetcar Named Desire, probably didn’t hurt either.) Weisbart’s leadership was equally appealing to Siegel. Both were fraternal members of the Warner Bros editorial diaspora, and Weisbart loyally held Siegel’s back as the director ignored Skouras, smoothed out script kinks with Huffaker (brought in after Johnson washed his hands of the enterprise), and hastily recast the female lead after Barbara Steele either jumped or was pushed from the role depending on whose recollection you prefer.

Flaming Star (1960)

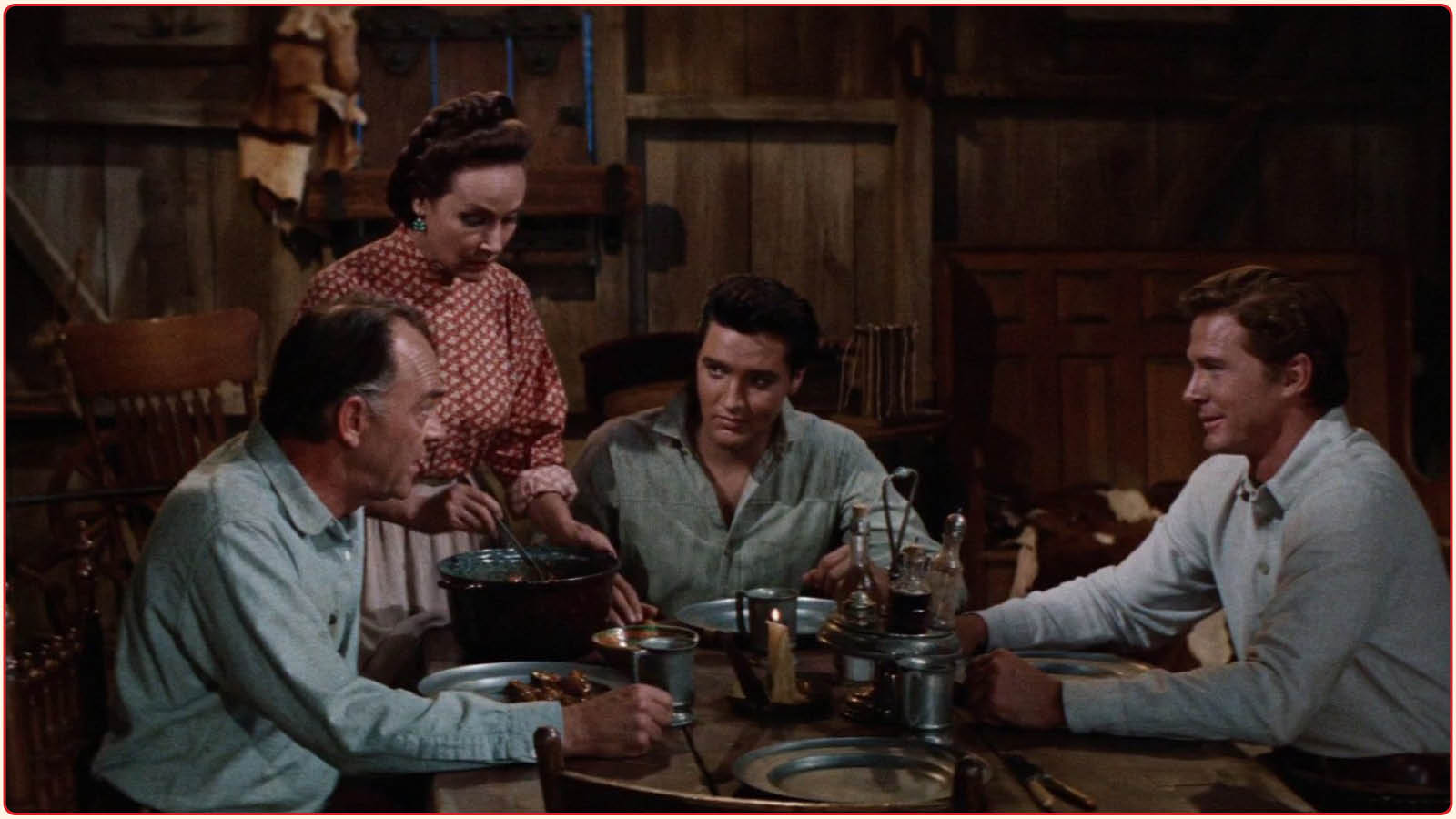

Huffaker set Flaming Star on a barely settled 1870’s Texas frontier where two prior decades of simmering resentment between the increasingly displaced Native population and their increasingly entitled colonial usurpers has reached boiling point. Within the contested hills (played by the Conejo Movie Ranch: the same Thousand Oaks location as Siegel’s first Western, 1952’s The Duel At Silver Creek; and Johnson’s scripted dustbowl in John Ford’s 1940 The Grapes Of Wrath, among scores of others), the racially blended Burton family works a small cattle concern while deliberately staying as far out of the fray as their obligations to both sides of the conflict permit. Presley plays Pacer Burton—the spawn of first-generation settler Sam and his wife Neddy, a full-blood Kiowa literally purchased from her tribe some 20 years past. Western film ubiquity John McIntire ably fills Sam’s boots while Neddy is played with 19th-century theatrical intensity by Doloros del Río—onetime silent screen “female Valentino,” Fred Astaire dance partner, Orson Welles paramour, and an Emilio Fernández screen muse second only to María Félix. Pacer’s stepbrother Clint (Steve Forrest, occupying a spot on the empirical table of lightly lugubrious second-tier leading men somewhere between Barry Sullivan and Cameron Mitchell) is poised to marry Roz (Steele’s replacement, Barbara Eden) despite her family’s frequent tactless reminders of his apparently unforgivably non-white stepmother and stepbrother’s heritage. Egged on by messianic Kiowa revolutionary Buffalo Horn (Rodolfo Acosta), the Natives bend the fragile peace to breaking in a series of brutal guerilla raids that fan the embers of racially tinged enmity between the town folk and the Burtons, who are left, in the eyes of the “terrorized” town, suspiciously unmolested. In rapid succession, a white posse provokes a brief but violently galvanizing showdown with Pacer, Clint, and Sam, followed by a clandestine visit from Buffalo Horn himself hoping to recruit Pacer to the Kiowa side as a priceless PR coup for the long fight ahead.

Needless to say complications ensue. Arguably the movie’s theme song describing a flaming star inevitably claiming every man’s life is itself a spoiler. Trapped between an unabashedly racist community that literally votes to let his gravely injured mother go untreated, and a Native tribe whose wedding gift to Neddy was saddling her with the Kiowa language calque “the thin woman who deserted her people,” Pacer’s fate is frankly sealed from the get-go. “It’s just plain hate now,” he bleakly observes as the bodies pile up, “anybody’s looking to kill anybody who isn’t just like ’em.” His family thinned to near extinction by both sides, Pacer makes the most of his brief remaining future by avenging the dead and protecting who’s left, reasoning, quite logically under the given dramatic circumstances, that if it’s “gonna be like this the rest of my life, then to hell with it.”

Guralnick characterizes the Flaming Star shoot as something of an undeclared psych war between Siegel, eager as he frequently was throughout his career to take an up-and-coming artist under his wing, and Presley, who interpreted Siegel’s ministrations as Tinseltown condescension. Siegel himself is a self-aggrandizing boor about the experience in his largely useless memoir, A Siegel Film. But happy or not, their resulting collaboration is a corker. DP Charles G. Clarke, an undeservedly unsung Fox below-the-liner makes the most of the proceedings, delivering day for night frontier lunar landscapes and vividly lit dollops of pre-Bonnie and Clyde (1967) Grand Guignol violence rivalling anything else in Fox’s estimable gallery of decorously weird CinemaScope Westerns of that era (cf. Henry Hathaway’s 1954 Garden of Evil, Sam Fuller’s Forty Guns, and Ray’s The True Story Of Jesse James, both 1957). Neddy staggering with UFA silent intensity across parched earth in a bloodstained Mother Hubbard, Pacer stripped to the waist and war-painted in his sibling’s gore while barely outrunning arrows sparking on rocks beneath his feet, a massacre presaged by an offscreen concertina sigh, and character actor L.Q. Jones catching a fast hatchet to the face are all top-shelf instances of Seigel’s unique gift for acutely vicious visuals. The finished film even impressed its spurned creative bridesmaid. According to Dorris Johnson and Ellen Leventhal’s collection of his letters, Nunnally Johnson found “Siegel’s direction commendable and was pleasantly surprised by Presley’s performance.”

Flaming Star (1960)

Flaming Star also marks an all-time low in the number of musical sequences Presley was obliged to endure. Not counting the theme (played over Pacer and Clint riding home in long shots intertwined via glacé-smooth optical transitions, another lovely hallmark of Fox filmmaking of the era), Presley performs exactly one song, “Cane and a High Starched Collar,” done and dusted less than five minutes into the film. Music and lyrics are the work of Sid Tepper and Roy C. Bennett, whose increasingly idiotic contributions to Presley’s screen musicals to come are some of the most memorably awful things about the films themselves. Indeed Tepper/Bennett compositions like “Ito Eats” and “Song of the Shrimp” dominate Elvis’s Greatest Shit, an infamous bootleg LP and necessary trial of my early ’80s personal Elvis red-pilling. In Flaming Star, Tepper/Bennett contribute a mercifully innocuous faux folk tune solely notable for being (after the G.I. Blues title song) their second Elvis screen number in a row containing a verse that rhymes the word “chow.” Siegel’s busily efficient staging begins with Elvis casually unstrapping his six-gun, picking up a guitar, and crossing into a perfect profile as the song, such as it is, takes hold, then climaxes with co-star Richard Jaeckel tributing the infinitely superior 1957 movie hit “Jailhouse Rock” by dancing with a wooden chair per the lyrics of that genuine showstopper.

Setting aside Cyril J. Mockridge’s unobtrusively generic score, the film’s real music comes from its cast’s voices: McIntire uses his squeaky oaken hinge delivery and shambling underbite gravitas to reveal a father and husband slowly crushed under the weight of persecution and loss, appearing to age a decade over the course of the film’s barely weeks’ worth of tragic incident; Forrest’s distinctive Texas by way of the Pasadena Playhouse accent, hailing Presley’s character as “PAY-suh” in good times and “pay-SUH” in bad in a near Stanwyck-ian burr, is a sadly extinct Hollywood spoken-word riff all its own.

It’s tempting to infer that the interiority driving Presley’s unwaveringly brooding and quite self-possessed performance stems from the own highly insular family background. “The three of us formed our own private world,” Elvis’s father Vernon once observed about the King’s only-child childhood. Tragedy had followed Elvis his whole life, after all. Hadn’t his birth been cruelly heralded by a stillborn twin brother? Surely the bitterly aggrieving loss of his 46-year-old mother Gladys to cirrhosis and hepatitis just weeks before he shipped out to Germany offered a kernel of real experience from which to cultivate the fictional truth in Pacer Burton? All fun to consider but, alas, a necessarily un-documentable conjurer’s secret of acting that will—and should—never be revealed. One might just as well say that Forrest’s own performance was somehow informed by his offscreen eternal second banana status as better-known leading man/Preminger heartthrob Dana Andrews’s real-life sibling. Perhaps it was.

The chemical reaction driving Presley’s gracefully relentless performance is better documented. He returned home from Germany with two destiny-altering fascinations: an infatuation with 14-year-old Airforce brat Priscilla Beaulieu, and the dawning of a lifelong appetite for amphetamines. While on maneuvers at Grafenwöhr, a stretch of wilderness that had previously hosted training exercises for the German Imperial Army and the Nazi Wehrmacht, Presley received his first taste of speed in the form of Dexamyl tabs helpfully provided by a motivating sergeant. For a lifelong sleepwalker and insomniac already inclined to burn the candle at both ends, it was love at first hype. Presley and his boys soon were trading under the table cash for PX jars of the same little white pills that had revolutionized interstate trucking and kept 20th-century creatives from Orson Welles to Ayn Rand to Gene Roddenberry either camera-ready svelte or on deadline or both. Presley, first generation Memphis Mafia mafioso Red West revealed in the scurrilous tell-all, Elvis: What Happened, “really took to them pills. He liked what they did for him. So did we all.” Back in the states, it was easy enough to obtain a script to keep the 24/7 party going. Certainly in Hollywood. On the set of Flaming Star, said West (who briefly appears as a Kiowa foot soldier), “We were higher than kites all the time.”

What Dexamyl “did” for Presley was keep him heedlessly energized, and impatiently harpooned to the given moment. “From G.I. Blues on,” West maintained, “you can notice the way he speaks. He had to make a real effort to slow his speech down.” But in Flaming Star a film that, in Siegel’s conception, foregrounded action over dialogue, Dexamyl was Presley’s secret weapon. Starved to rent boy perfection and ruched into a wardrobe that appears to increasingly constrict his frame as the dramatic stakes rise, Presley, with next to no extraneous chatter to manage, let his bronzer-slathered body, drug-hooded eyes, and a face that flickers from pudding to marble and back in closeups do the work. Fingertips dangling like anemones (a Presley physical trademark Jacob Elordi nailed in Sofia Coppola’s curiously inert biopic Priscilla), the doomed and damned Pacer seems like he’s running for his life even while standing still. It’s no coincidence that Andy Warhol’s 1963 fetishistic pop art silk screen portrait series of fast-drawing Presley was cribbed from a publicity shot for Flaming Star. In both Warhol’s and Siegel’s visions, Presley poses with legs spread, lip curled, gun drawn, and eyes flashing—counting down to blast off to the titular death star that would greedily consume both Neddy’s and Gladys’s boys on-screen and off.

Share: