Essay

Like In A Mirror

A new translation of Victor Erice’s tribute to Nicholas Ray.

Ray’s Wind Across the Everglades & Erice’s Dream of Light screen Saturday, July 26 in a rare 35mm double feature, as part of The Theater of the Matters: Ray x Erice.

Share:

In 1986, the ICAA (Instituto de la Cinematografía y las Artes Audiovisuales) of the Madrid Filmoteca Española published Víctor Erice’s book on Nicholas Ray, (co-written with Jos Oliver). The International Film Festival in Rotterdam published an English translation of this piece in their festival catalogue in 1991, but as far as we could find (thank you to Adrian Martin and Jonathan Rosenbaum for the guidance), it was never digitized. Here we have a new translation by Andrew Castillo. Special thanks to Mr. Erice for allowing us to publish this. —The Theater of the Matters

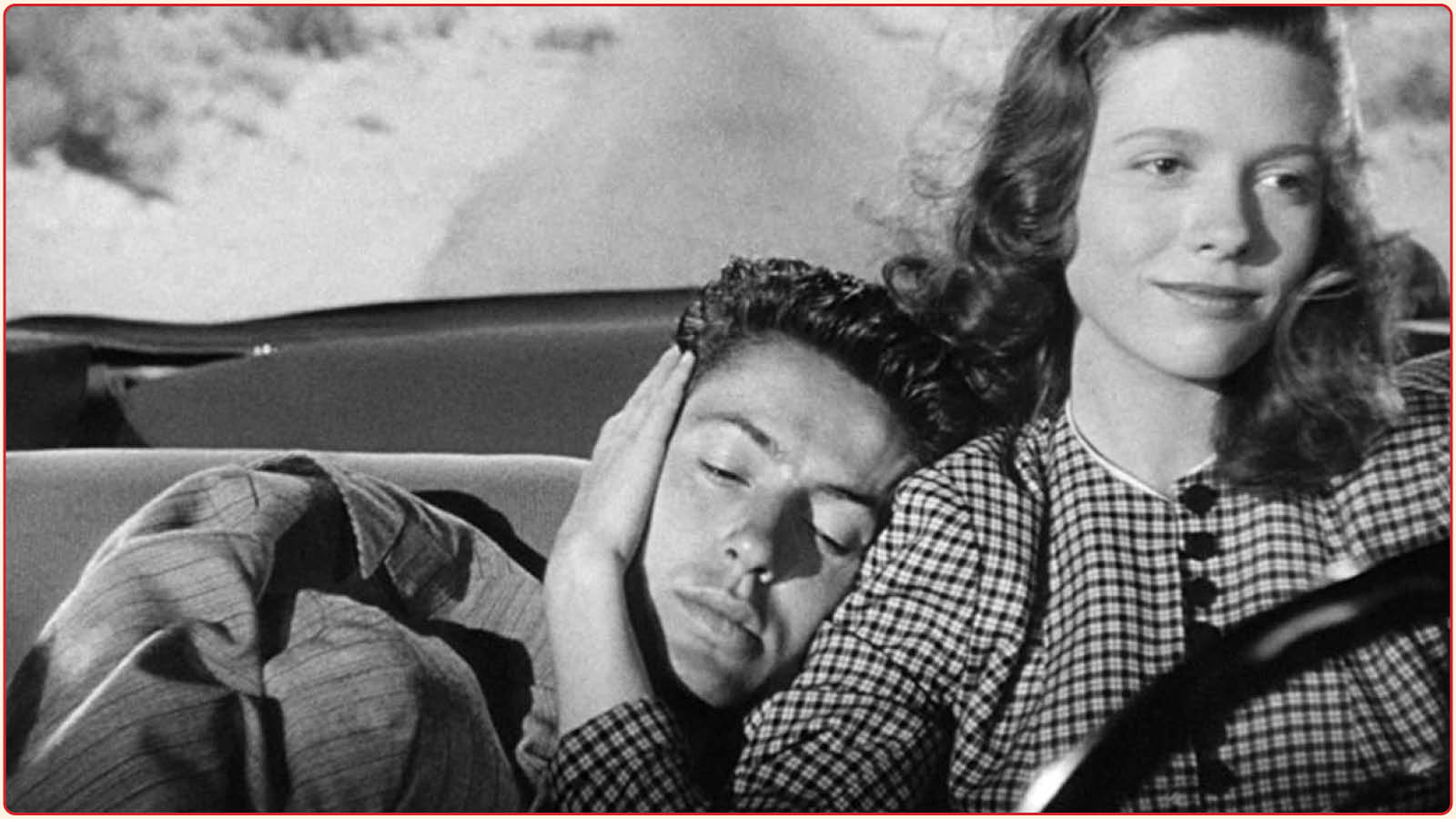

Wind Across the Everglades (1958)

Somber and limpid tête-à-tête

A heart become its own mirror!

Charles Baudelaire: “The Irremediable.”

“In my case, my whole life is redeemed by the adventure

of filmmaking, which ultimately gets mixed up with the

adventure of my own life.” —Nicholas Ray, 1974

– I –

The general outline of the story is more or less known. In the years between 1947 and 1963, decisive in the evolution of the cinema, Nicholas Ray directed a total of 20 films, shot in North America and Europe, the majority produced by the Hollywood-led industry. Then another 16 years, also split between two continents, marked by numerous projects that were never realized, from which a few marginal, unfinished and errant works emerge. Years of rupture and exile, of vital exaltation and illness, of uncertain moves driven by a growing instinct for self-destruction, of a chaotic and wandering search for new ways of living and filming; years that ultimately culminate in a final attempt, made on the threshold of death, to recover lost identity and self-respect through a film.

These two life cycles, far from contradicting each other, are complimentary, and form the indivisible whole of a cinematographic adventure in which life and work appear intimately unified, and, most essentially, are experienced to the end as a passion. Hence, the exemplary character of this adventure, and of the figure it projects. Not exemplary in the didactic sense of word, but in its unique and exceptional nature: the best of Nicholas Ray’s work will forever live in the space, real and imagined, of myth. A space that is ambiguous, like the figure it bears; and a myth that is, in the end, none other than that of the modern cinema.

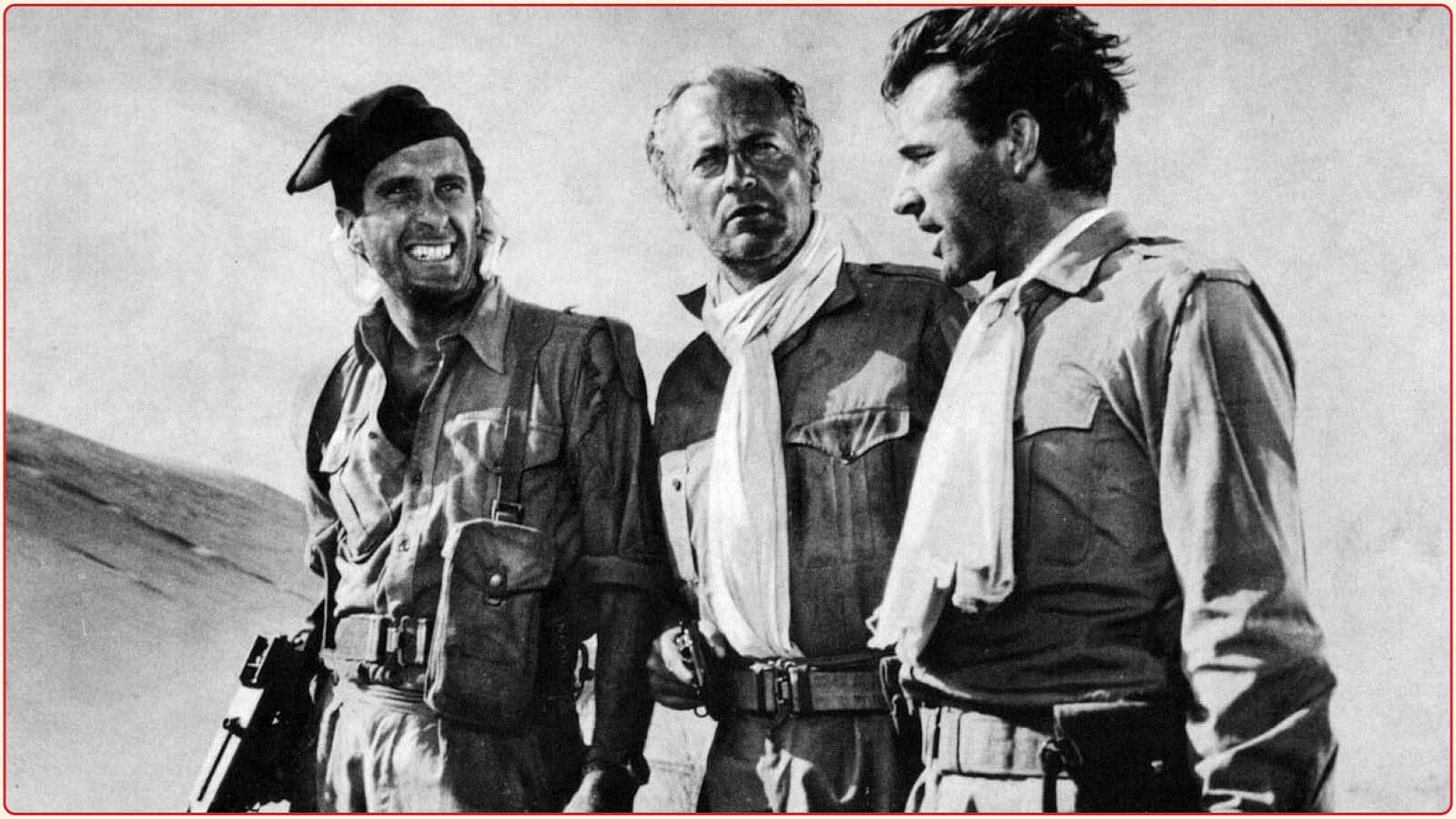

Perhaps before anyone else, Jean-Luc Godard knew this when, in 1958, a year before he directed Breathless (A bout de soufflé, 1959), after his famous proclamation that “the cinema is Nicholas Ray,” he wrote: “Why does one remain unmoved by stills from Bitter Victory when one knows that it is the most beautiful of films? Because they express nothing. And for good reason. Whereas a single still of Lillian Gish is sufficient to conjure up Broken Blossoms, or of Charles Chaplin for A King in New York, Rita Hayworth for Lady from Shanghai, even Ingrid Bergman for Elena, a still of Curt Jurgens lost in the Tripolitan desert or of Richard Burton wearing a white burnous bears no relation to Curt Jurgens or Richard Burton on the screen. A gulf yawns between the still and the film itself. A gulf which is a whole world. Which? The world of the modern cinema.” 1

– II –

Today, almost thirty years later, we comprehend with greater certainty what Godard meant, for the simple reason that all of his work as a director emanates precisely from the vision of that gulf. In this sense, Godard was not only an anticipant, but is also, particularly since Pierrot le Fou (1965), a survivor of himself.

Nicholas Ray had a different fate. Possessing a gaze which pulsated with the cinematic feeling of some of the great masters of the silent era, crystallized within his experience in classical cinema, he was probably the last of its most genuine representatives, and at the same time, one of the first models of modernity. A poet to the end, he resided at the bottom of that gulf, performing, with real courage and not without humor, the role that destiny assigned him: to embody the transition from classical to modern cinema, to exhaust that adventure until its consummation. The last film in which he took part, Lightning Over Water (1981), leaves no doubt about it. Godard’s claim from his review of Bitter Victory (1957) turned out to be true.

– III –

In the late 50’s, to discover that gulf opened up by Ray’s images implied an understanding of fiction that was distanced, even critical, very different from that of the classical filmmaker. Suddenly, fiction lost its transparency, and was transformed into something else (“It is no longer a question of either reality or fiction,” wrote Godard, “or of one transcending the other. It is a question of something quite different. What? The stars, maybe, and men who like to look at them and dream.”)1, a mirror in which young cineastes suddenly found their solitary image, caught in the trance of filming. Hence the sense of estrangement, and (as if attempting to mitigate the vertigo they experience) the newfound impulse that will lead them to frequently include themselves, directly or via an intermediary, in the images of their films, often highlighting the presence of the camera. This is the origin of a new class of directors—posers, as Serge Daney described them—who not only let 2 themselves be physically seen from time to time in their own films, but also cast some of the great filmmakers of the past, their old out-of-work masters, in order to better highlight their filial lineage.

Nicholas Ray lived this phenomenon in an extraordinarily singular and intense way. True to his character, he either did not desire or was not able to free himself from the fictions present in his works; moreover, at a certain point, having lost his identity as a filmmaker, he began to embody them more than ever in his daily life. Up until then, his films, more than their achievements and frustrations that continuously emerged over time, constituted his existence as an author. But without them, life was stripped of that primordial relationship to others and began to revolve around itself, becoming a kind of representation or simulacrum, depending on the circumstances. Melting into his dreams, the author gradually faded away, leaving behind the echo of footsteps that wandered from one place to another. The story, however, could not end there because Ray was always a director who, more than addressing or reflecting a theme, embodied it; and who, by carrying with him everywhere, was therefore fatally condemned to express it.

Dream of Light (1992)

– IV –

Based on available testimony, we can say that, from 1963 on, Ray lived to film or filmed to stay alive. He filmed whenever he had the essential technical means, with hardly any set plans, even without a story; the only possible story was that of Ray himself, determined to capture something unknown, the expression capable of reflecting the disjointed rhythm of his days. Within this obsessive impulse, those two essential actions— living and filming—tended to become the same thing, but on the condition that one of them— the latter—would never reach completion, would not be exhausted exposing the other. It is not surprising that, particularly as he made his way through Europe, Ray was leaving behind a trail of striking images, unedited, deposited here and there, in the most disparate places. Because the work, always in the process of being realized, was no longer discourse or communication of a meaning, but pure exteriority, expanded to infinity, endless; that is to say, a way to exorcise death.

Under these circumstances, the echoes of the fictions and most representative characters from his old works were returned to us in the form of the author turned actor, who made the search for himself the central theme of his final films. In this adventure, it’s clear that Ray, as he had done for most of his career in the industry, continued to risk it all. But when, from a certain point of view, nothing is left because everything has been lost, spent or squandered, what could the risk be? Although it recalls it in certain respects, this risk was distinct from that of the poser director because, at that point, day after day under the influence of alcohol and drugs, Ray had inscribed onto his body—testimony to his physical deterioration and illness, that “process of breaking down” that Scott Fitzgerald 3 spoke of—his own fictions.

The image of this condition is not new, at least outside of the cinema. Indeed, it is found in writers like Fitzgerald; also in Malcolm Lowry, Antonin Artaud and many others. But in the case at hand, what could the subject in question do when he was a director actor (as Ray preferred to present himself in public at the time) whose personal justification was filming? What he chose to do was to display himself. To show himself in images, in an act in that contained a little of everything: exhibitionism and a certain unavoidable impudence, mixed with an essential courage and sincerity.

In this radical experiment, the author (and with him his subject) breathed through a wound, such that the fissure, the distinguishing mark of his style, appeared open on his own body, thus becoming a fundamental sign. We were therefore as far removed from the gesture of the conventional exhibitionist as we were from the attitude—more reserved and ironic, but complicit—of the poser. Because this adventure was about something else, entirely: a tragic malaise that no longer had any other way of objectifying itself; that is, the embodiment of a form of destiny.

– V –

We Can’t Go Home Again (1973) is the beautiful and revealing title—evocative of the work by the writer Thomas Wolfe—of the unfinished film on which Ray worked until his death. In it he incorporates his own role, that of Nick, an old and famous Hollywood director who, following an unsuccessful attempt to make a film about the Chicago Seven trial of 1969, survives by teaching at the university. The relationship this character establishes with his students is shaped by the work they carry out together—the shooting of a film—a sort of total experience where everyday life as a community project and cinema as a collective creation are meant to be united. Despite appearances, it is about a somewhat circumstantial alliance, a pact between survivors of two different shipwrecks who, by chance, have come together on the same desert island. For one of the reasons for this unique undertaking, which also serves to intertwine the stories of its protagonists, is none other than the search for lost identity, as a man and a filmmaker, of the subject who provokes the action. A teacher who is as confused as his young disciples, a father who seems as lost as his adopted children, but who is willing to risk everything to find, what, no one exactly knows: an answer, a clear sign, perhaps the path that will return them all to that mythical home of origin, a transparent vision of fiction where, it is said, true fraternity once existed. But, after going through several crises, the experiment ends in failure: Nick hangs himself from a beam, in front of his students.

– VI –

Lightning Over Water, filmed in 1979 with the essential participation of Wim Wenders, is in a sense the continuation and completion of We Can’t Go Home Again. The idea guiding Ray’s action in the film—as he himself publicly declares at Vassar after the screening of The Lusty Men (1952)—is practically the same: to recover his identity and self-respect, but this time with the lucidity that comes from knowing he is about to die. It is a classic project par excellence—in which death is not something granted, but something that must be done—which Ray, more faithful than ever to his artistic origins, wishes to present in terms of dramatic fiction: Lightning Over Water, the story of a once-famous sixty-year old painter who is sick with cancer, and dreams of travelling to China with a friend suffering from the same disease to find a plant of legendary medicinal power, which may be capable of restoring his lost health. This story is challenged in a significant scene by Wenders, a poser, who is concerned with the question of cinematic realism, no longer believes in innocent fictions, and who somehow senses that the subject of the film is something else altogether. His questions (“Why make the detour of turning him into a painter? Because he’s got your name. Why isn’t he you, and why isn’t he making films instead of painting? It’s you, Nick. Why take the step away?”) act as a cancer to the narrative, bringing about a transformation of the story (all of the people on screen will play themselves), while giving free rein to the images recorded on video, which, with their “impression of reality,”—Wenders’ own assessment—“answer” those filmed in color negative.

Wenders’ gaze, which seems as divided as his crucial willingness to go along with the project, is essential as an element of confrontation—the one established between he and Ray—and becomes the main driving force of the film. In this scenario, Wenders is forced to assume the role of the antagonist—that is, the advanced disciple, materially capable of completing the production—who nevertheless experiences filiation as a conflict: a theme that, not coincidentally, occupies a central place in Ray’s filmography. As such, this transformative experience, regardless of any value judgments it might merit, more than just constituting an unrepeatable testimony, is far from devoid of meaning. In any case, from a certain point on, the confrontation can only be resolved in one way and the fate of Lightning Over Water is sealed, flowing towards its natural outcome: the death of the protagonist.

Nicholas Ray has failed to carry out his project of having a death of his own, but his radical plea amidst the confusion and helplessness makes his failure a powerful claim to authenticity, an affirmation of life in death. “Defeat alone,” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre, “by stopping the infinite series of his projects like a screen, returns man to himself, in his purity.” 4

In the same way, the figure of the disciple can now appear to us in a new light, as a necessary figure of destiny, one whose delicate mission has consisted, above all, in returning the master to his essential solitude, so that, having exhausted his life cycle, he is able to proclaim the definitive Cut!

They Live by Night (1948)

– VII –

The adventure has been consummated. In the final images of Lightning Over Water, Ray’s body is a handful of ashes stored in a jar, deposited with a camera and a Moviola on the deck of a junk sailing down the Hudson River toward the sea. Below deck, a group of people, coincidental companions in the adventure, celebrate a funeral rite and, somewhat compulsively, share conversations, toasts and satisfied laughter, like all survivors who rediscover the most banal and everyday aspects of life. The image of the junk freezes; then, superimposed, the trembling handwriting of the deceased appears.

While Ray was alive, his words belonged absolutely to him; in death, they have become community property, and Wenders naturally feels entitled to use them in an act whose effect is twofold. At this point, it’s hard not to recall the unforgettable phrase uttered in the desert by Richard Burton in Bitter Victory: I kill the living and save the dead! For Ray, living was a dramatic conflict, a final attempt to rewrite one’s origins, to transform memory into a useful act, and duration into a meaningful time; that is to say, a movement of the spirit, unfolded before society’s eyes, still lacking the unity and meaning that could only bestowed by death.

Thirty-two years earlier, in the final scene of They Live By Night (1948), Keechie reads the letter that Bowie wrote her before his death. In Lightning Over Water, the final words come from a fragment of Ray’s diary, a sort of message in a bottle addressed to everyone and no one, which establishes, despite the differences, a parallel between the endings of the two films. Bowie’s in They Live By Night were words of life, affirming their love by invoking the future, the child held in Keechie’s womb (“I’ll send for both of you when I can. No matter how long it takes, I better see that kid”). Ray’s in Lightning Over Water emerge from a desolate vision of the present, and turn towards a past without code, timeless. Situated for the first time off-screen, Wim Wenders reads them both a posthumous prayer: “I looked into my face and what did I see? No granite rock of identity. Faded blue, drawn skin, wrinkled lips and sadness. And the wildest urge to recognize and accept the face of my mother.”

That face marked by the sign of mortal illness and the passing of days, in which it is hardly possible to distinguish a single feature of the lost identity, turns to that of a primordial figure, mediator between the darkness from which man comes and the world, longing for recognition. Expressing an intense nostalgia for his origins, his words are both the symptom and the consequence of failure. But a failure that, by the nature of the endeavor—the search for an impossible unity—affects us all. From the ashes of this passion, Nicholas Ray’s work is reborn as an example of universal character, a mirror in which we can all recognize ourselves, a poem where cinema and life appear fraternally united.

This text written by Victor Erice in 1985 appeared in Nicholas Ray y su Tiempo, Filmoteca Española, Madrid, 1986. This new version was revised by the author in January 2011 for publication in Shangrila: Derivas y ficciones aparte, No. 14-15.

Newly translated from the Spanish by Andrew Castillo. Castillo is a record collector and cinephile from the Bronx. He has presented film and music programs at the Maysles Documentary Center, Light Industry, Spectacle Theater, Lot Radio & WKCR-FM.

1 Jean-Luc Godard, “Au-dela des étoiles”, Cahiers du cinéma, no 79, January 1958 (as translated by Tom Milne in Godard on Godard, 1972).

2 Serge Daney, “Wim’s movie”, Cahiers du cinéma, no 318, December 1980.

3 F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up

4 Jean-Paul Sartre, Qu’est-ce que la littérature?

Bitter Victory (1957)

Share: