[wpbb post:terms_list taxonomy=’category’ html_list=’no’ separator=’, ‘ linked=’yes’]

[wpbb post:title]

Lawrence Lek. Photo: Ilyes Griyeb. Copyright The Artist, courtesy Art Basel.

[wpbb post:terms_list taxonomy=’category’ html_list=’no’ separator=’, ‘ linked=’yes’]

BY

[wpbb archive:acf type=’text’ name=’byline_author’]

An interview with filmmaker, visual artist, and musician Lawrence Lek about his 2019 debut feature, AIDOL.

Lek’s AIDOL and Geomancer play at Metrograph as part of Cantopop Icons, both at 7 Ludlow and At Home.

In April 2019, the London-based filmmaker, visual artist, and musician Lawrence Lek was joined by musician and sound artist Steve Goodman at Sadie Coles HQ gallery in London to discuss Lek’s debut feature, AIDOL (2019). The 2065-set, CG-rendered, pop music provocation tells the stories of Diva, a former celebrity preparing to make a comeback performance at the Olympic eSports finale, and Geo, the aspiring songwriter AI she enlists to aide her. This is an excerpt from Lek and Goodman’s conversation about the spellbinding sci-fi musical, which ruminates on the future role of AI in creative endeavors, the influence of tech giants over all fields of culture, and the human impulse to chase after fickle fame.

STEVE GOODMAN: I read an interview where you identified in your work questions over your fears as an artist of becoming obsolescent, whether it be obsolescence in the general economy of the art world or being made redundant by AI. Could you talk a bit about how that comes through? There are a lot of existential questions relating to artists in Geomancer (2017), which is like a portrait of the AI as a young artist, and also specifically to do with music and AI in AIDOL.

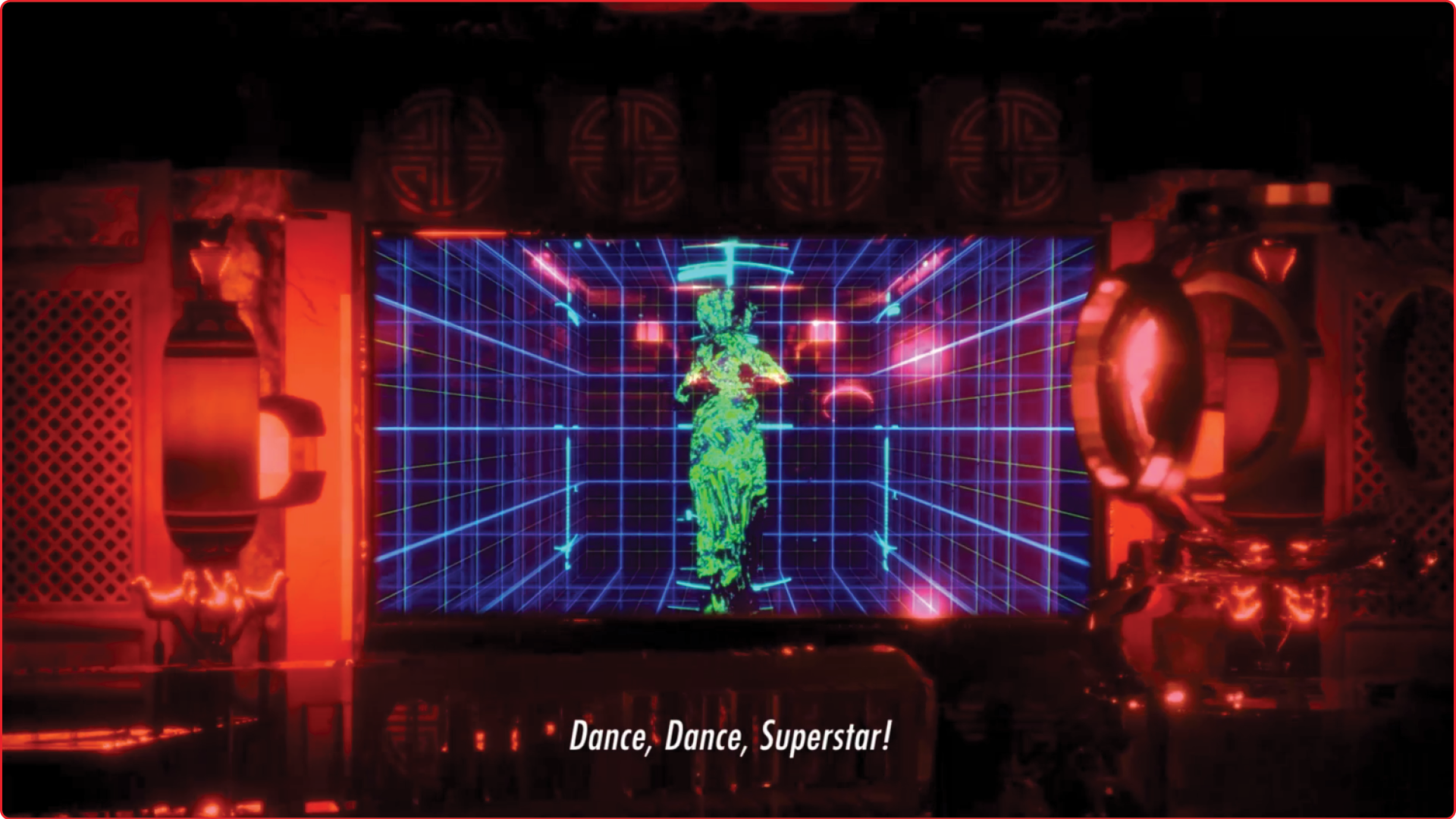

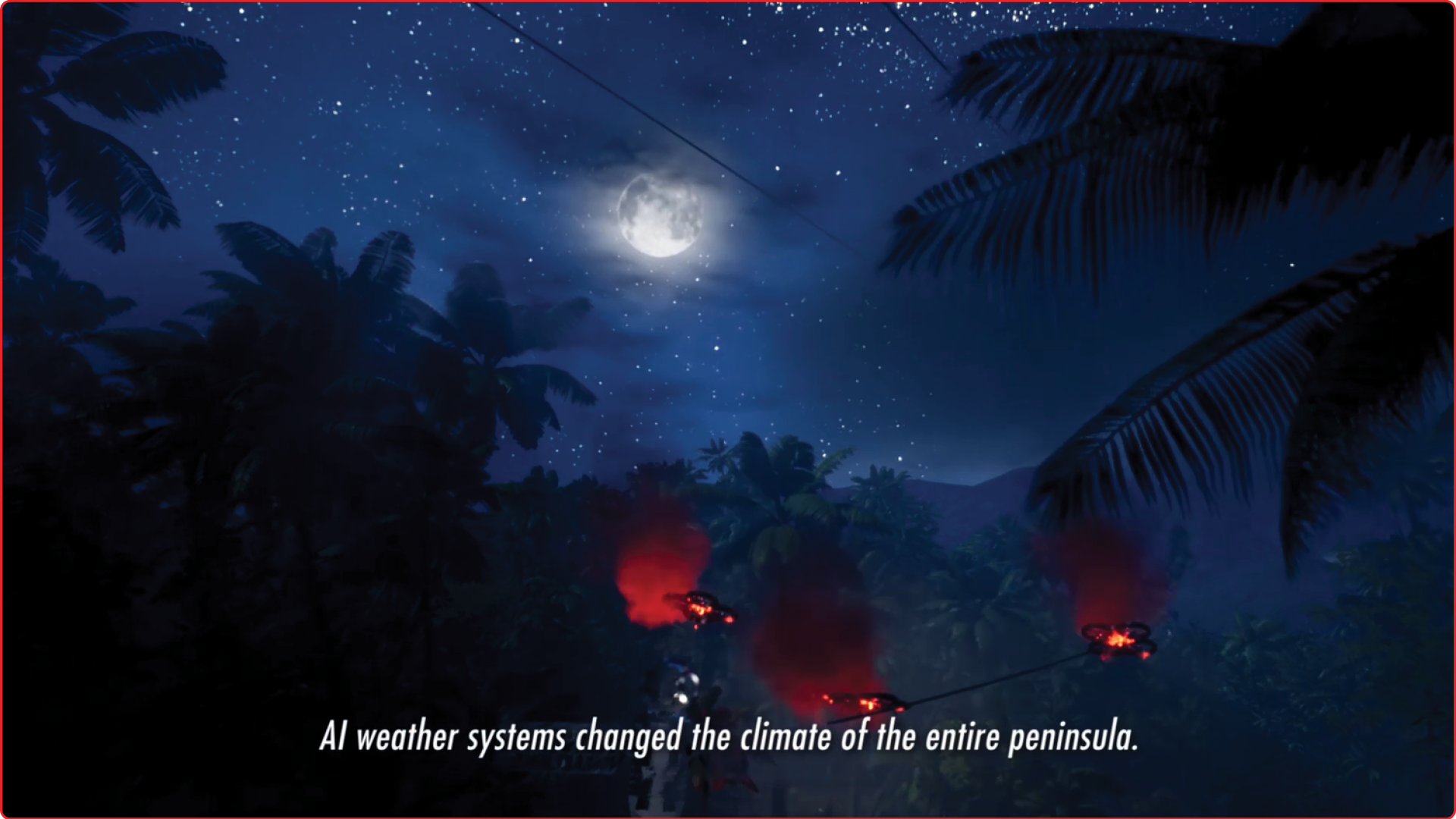

AIDOL (2019), [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.

LAWRENCE LEK: Yeah. Whether it’s about music or about making work, many of my thoughts, hopes, and fears are written into a script and embodied in characters. Because Geomancer and AIDOL have many biographical, theoretical, and historical aspects, each of those works become dense and overdetermined. It’s the point where personal concerns from the present day somehow combine with Malaysia and 2060s Southeast Asia. But the way I’m trying to use biographical details is to fictionalize them. For me, that’s a fundamental way to get some distance from the specific details of a given context, so that the work speaks to more universal concerns. Before Geomancer, every project I made was site-specific. My question was: what does this idea of site-specificity mean in an increasingly virtual and ephemeral age? The question came from architecture, land art, and sculpture-but how does it relate to cinema derived from virtual worlds? I thought that a new narrative could emerge from going into the history of the place, really talking to people who were there, who lived through it, who live there now, and trying to build a link between this idea of the virtual and the idea of the real. What I found limiting was that the more site-specific or more time-specific something was, the more it remained an artefact of its own time and place. For example, if you look at a line-up from a music festival in 2016, it’s like ancient history. The way time progresses, I felt, was just incredibly relentless. It’s the same in every creative industry-trends, fashions, cycles, and so on.

This feeling had much in common with the spirit of another age, like the jazz age or fin de siècle Europe: what do you do when the world changes so fast because of technology and society that all your bearings no longer hold? I felt it was important to write those concerns about obsolescence and art into the work. The question then became not what happens when I’m useless, but what happens when everyone’s come to terms with that state? Because after people stopped being tied to the field, or to servitude, or to a certain form of labor, they found something else to do, right? I think the problem of finding something else to do is ultimately an existential one, especially if you’re an artist or creative producer. Geomancer takes this idea of the portrait of the artist, or artistic awakening, or a coming of age narrative-which as human beings we generally associate with going to school, being a teenager. It’s important to revisit those questions periodically. So that’s kind of what Geomancer and AIDOL are also about.

I can imagine in 10 years’ time, there’ll be an Adobe button that’s just auto-generating a film based on your life story. It’s like, “Steve, autogenerate a film about exciting music narrative,” or whatever. I can see that happening, it’s just a confluence of a few different technologies for automating creativity happening. I can’t deny the worth of that, because I wouldn’t have been able to make this film on basically a couple of computers if most of those tools, and semi-automation, did not already exist. I’m within that web already, and I don’t feel that searching for authenticity, or originality, is anything other than a romantic ideal-even though by nature, I am pretty sentimental and emotional. I don’t think that’s a place that’s productive to dwell in, at least creatively.

AIDOL (2019), [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.

SG: It’s interesting, because all of this plays out in the narratives of Geomancer and AIDOL. In AIDOL, you have this neurotic pop star, Diva, who used to be in a band called The Synths in the 2050s, and she-or the company that she’s signed to, Farsight-is trying to rejuvenate her career. The record company is quite clear about what they want. There’s a question of pop stars’ obsolescence there, but it’s interesting the way the record company deal with her: they’re looking for the most generic thing possible, for something that’s immediately attention-grabbing, all the clichés of pop music, crystallized, distilled, automated-but not automated, because they’re Bio-Supremacists, who value human creativity. The relationship between Diva and Geo, an AI, is interesting, though. Geo allows Diva to complete the song she needs to perform at the eSports Olympics, so it’s a tangled web. Geo says that she, or it, came to SoMA, the School of Machine Art, to learn how to create, not to predict the future. And then in a later conversation, Geo’s worried about being generic, and Diva’s like, “Oh, that’s perfect. I need you to help me plagiarize myself. You misunderstand genius, machine learning killed the culture of originality. So just absorb everything I’ve done before and regenerate my music for me.”

LL: Well, in music, there’s this idea that you always have to reinvent the wheel, you have to do something different each time. I wanted to play on this idea of not just originality and variation, but also from an economic point of view. First, I observed this weird paradox that death is good for sales. Death is great for sales because it gives a finality to things. It’s the time to have retrospectives, where fans, friends and family share their condolences, records get reissued, and holograms get made. Basically, the end of life brings hype, hype brings sales, and sales bring a form of immortality to an artist’s work that they might not have had in their lifetime.

SG: There’s also a sense that Diva’s potentially quite old, and is only being kept alive by these immortality drugs provided by Farsight called Life. Diva’s going, “I need more Life, I need more Life,” and the record company is saying, “Finish the record, and we’ll give you more Life.” I don’t know how old Diva is, but she seems pretty desperate for more Life.

LL: There’s a couple of pharmaceuticals that pervade the film. One is Life, this drug that’s for longevity, and the other is SoMA-which is the acronym for the School of Machine Art, so the idea is that training at the AI school is like a kind of drug in itself. Soma was from Brave New World. It’s the drug people take to be okay with the state of the universe; it’s a placebo/antidepressant. In AIDOL, similarly, it’s not about the drug as an upper or a downer, it’s the drug that just keeps you cruising through. So, Life is there to signify this Faustian pact that Diva has, or any creator has, between the life they want and the sacrifices they make to achieve that.

In Diva’s case, the price is anonymity to achieve immortality; because she is essentially faceless, anyone can be her. Of course, there are the conversations about Vocaloid [anthropomorphic voice-generating software] stars like Hatsune Miku being the same thing; fans can be her, and have this weird kind of ownership/empathetic relationship. The classic 20th-century version of star and fan is very different from the 21st-century version, which is more about influencer and audience, because there are less barriers between an individual, their creative work and their audience, especially with live streaming, platforms and so on.

AIDOL (2019), [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.

SG: You also propose this question of super intelligence. The quote is “To be a musician, is it to produce music without musicians? Or architecture without architects, games without gamers, philosophy without philosophers, and influence without influencers?”

LL: Yeah. To go briefly into the other side of what I was thinking about, it’s not just the culture of stardom and influencer-or essentially, the culture of culture. Of course, a big question in culture and politics is the idea of surveillance: big data, people watching you all the time, creating a data profile of you based on shopping habits, anything they comb online. But how it relates to music is fascinating. I always think music, because of its very nature as sound, can be very easily commodified, but at the same time the experience of it resists that commodification, because sound does not have a physical presence when it’s actually transmitted. It can have a physical embodiment when it’s distributed, but the act of perception is something beyond, and really goes beyond an object. Because of that, it’s always at the forefront of new methods of distribution and intelligence.

For example, the intelligence that SoundCloud or YouTube or Spotify have of listeners is incredibly granular. Not just the relationship between different tracks, or genres of music that you like based on your listening profile and age, but also, very simply, when you start and stop listening to a track. There’s more information about your listening time; it’s like, you stopped at 12 seconds, 594 milliseconds. From a commercial point of view, a song needs to somehow capture your attention so that you listen to 34 seconds. Then after the 34 seconds barrier’s up, maybe you might listen to the whole three minutes. The whole durational thing totally changes. Pop songs now follow a different beat.

This is an excerpt from a conversation that took place at Sadie Coles HQ, which can be viewed in full online here. Lek’s current exhibition Black Cloud Highway 黑云高速公路 is on show now at Sadie Coles HQ at 1 Davies Street, London, until Saturday, June 24.

Steve Goodman is a musician, sound artist, and founder of the record label Hyperdub. He produces electronic music under the name kode9 and is also a member of the sound art collective Audint. He is the author of Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (MIT Press, 2012).

AIDOL (2019), [still]. © Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.