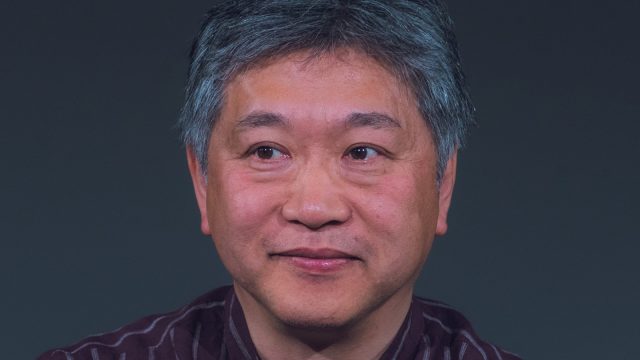

Hirokazu Kore-eda at Graumans Egyptian Theatre in 2025, photo by Kevin Paul.

Interview

Hirokazu Kore-eda

The master of meditative cinema on one of his most bittersweet humanist portraits… about a blow-up doll.

Air Doll (2009) plays at Metrograph from Friday, December 26 as part of Doona, Doona, Doona.

Share:

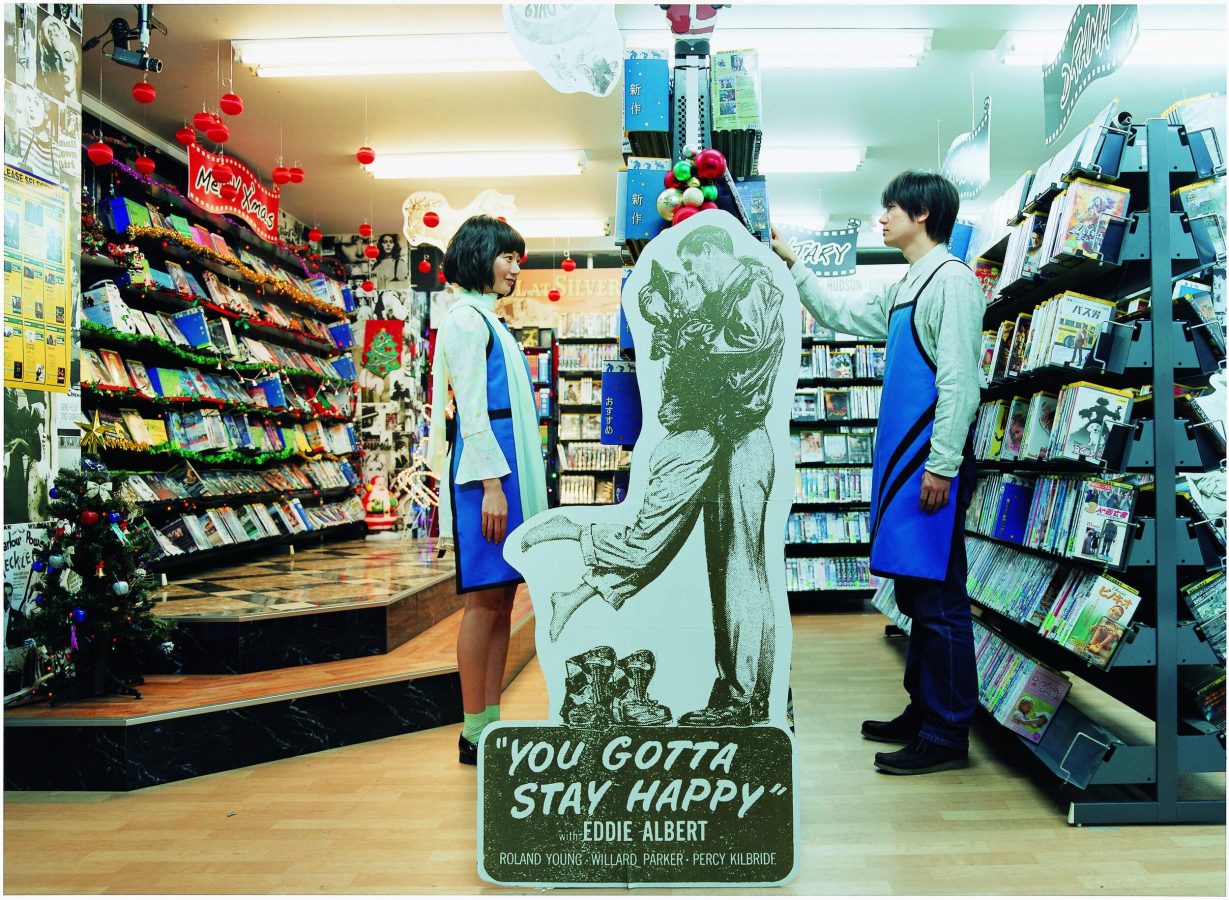

THIS FORMERLY UNPUBLISHED INTERVIEW TOOK place in 2010, one year after the release of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s film Air Doll, during one of my research periods in Japan, conducted at TV Man Union, the company where Kore-eda worked before forming his own production company, Bunbuku, along with several other directors. The film, based on the manga series of the same name by Gōda Yoshie, stars Korean actress Bae Doona as an inflatable sex doll that miraculously comes to live and discovers the challenges of being a woman in contemporary Japanese society. Air Doll marks one of the filmmaker’s most compelling, if somewhat neglected among his impressive oeuvre, featuring an impressive lineup of collaborators that includes Doona, Japanese actor (and fashion designer) Arata, and DP Mark Lee Ping-bing, a frequent cinematographer for Taiwanese luminary Hou Hsiao-hsien. I spoke with Kore-eda about the questions the film raises about love, womanhood, patriarchy, and his formidable craft. —Linda C. Ehrlich

LINDA C. EHRLICH: I’m a big fan of Air Doll and I was surprised that the screenplay was written by a man. It felt like it was created from a woman’s point of view. I was very impressed. Do you think that a doll coming to life is something limited to women?

HIROKAZU KORE-EDA: That’s a difficult question. What were the most memorable lines of dialogue for you among (the sex doll) Nozomi’s [Bae Doona] lines?

LCE: The fight dialogue, and the times when Nozomi is discovering herself during her conversations with Arata’s character [Junichi], when she asks: “What is this?” or “What’s the ocean?” and so on, and how he responds.

HK: What was difficult was considering how a doll would “think.” One aspect I was exploring was if she could overcome the damage caused when she realized she was conceived as a doll, a tool for sexual gratification, as she was discovering her own identity. Another aspect came about from discussions with actress Doona Bae about how to portray her character. I suggested mimicking a newborn baby’s exploration of the world around her using all five senses, rather than trying to act like a doll. Feeling cold… moving toward objects of interest… imitating things… It’s a story about the growth process of one woman who is yearning for the things those around her have, but she doesn’t. Growing from a baby to a wrinkled old lady. Experiencing the entire process in a short period of time.

We agreed on this approach. I think she portrays both themes: one, showing the happiness of becoming human; and the other, the sadness of only being a doll. How she combines both themes was the most important point; the most difficult, but also the most interesting.

LCE: What was the first stimulus that brought Nozomi to life [in the film]?

HK: I think there are two ways to answer this question. One is to say, “I don’t know.” It’s the same way as asking how we came to be alive. Some characters in the film exhibit this kind of thinking. Another possibility is that she was brought to life by the power of love from the man she was living with.

LCE: I believe Air Doll shows the paradox of love.

HK: The paradox of love…hmmm. I think it’s a film that can be interpreted many different ways. This is not an attempt to dodge your question. One can discover many metaphors in the problem of being physically empty and feeling emptiness. I think what metaphor is drawn depends on the person watching the film; it will also change according to when one watches it. It’s a very tragic story so while I didn’t consider the word “paradox” while creating it, I did keep in mind themes from The Little Mermaid: impossible love, being unable to overcome differences within intimate relations. It’s a theme explored in many different movies. The mermaid longs to be human and the struggles she faces after becoming human. Even though one theme was an exploration of the failure of an interspecies relationship, I didn’t want to just portray a tragic story. Rather than portraying Nozomi’s “emptiness” as something negative, a deficiency, I wanted to show that it provided opportunities to connect with others.

There’s a short manga that’s the base for this movie. After reading it thoroughly, I thought the way it set out to portray a sense of emptiness being fulfilled by another person was wonderful. At the end of the original story, too, the doll is thrown out in the garbage and dies, but I thought that the view of life and humanity that lets us see the potential of this act was very rich. I believe that living things do not develop independently; rather we are developed by others filling in our deficiencies and we fill in the deficiencies of others. Trying to fill these deficiencies by oneself can result in unhappiness. So I thought the view of life and humanity that sees these deficiencies fulfilled by someone else gives a sense of abundance (yutaka). However, people often don’t realize this, so I wanted to make a movie showing a doll coming to realize this way of thinking.

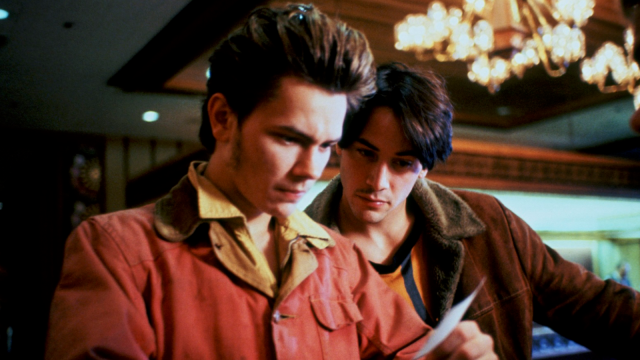

Air Doll (2009)

LCE: I was shocked by the scene when Junichi is killed.

HK: From my perspective, the reason she killed him is that she has grown and developed so rapidly; she experiences many misunderstandings, but she feels happiest when she is filled with the breath of someone she loves. She feels fulfillment. As a result, she wants to give the same experience to the one she loves and accidentally kills him. This is the direction I gave when the scene was acted out. She didn’t kill his character out of spite or with the intention to kill him. Her desire to fulfill him with her breath, fulfill him with her love, led to that tragic ending.

The character Arata played was the kind of personality attracted to death. By the end of the story, I wanted to show that the doll was the most human . Placed around her are people with a kind of twisted emptiness. There’s a contrast between the man who is pulled towards death and Nozomi’s approach to life. Because he is facing death, he does things like decorate his house with dry flowers. Therefore, although the two of them love each other, there is a difference between the love she feels and the love he feels… the desire she feels and the desire he feels… This is somewhat embarrassing but, when she loses air and has air blown into her belly button, when she is filled with his air, it is a kind of orgiastic experience. As for the man, he is reacting to her shriveling up. After having that experience, she decides not to inflate herself again and throws away the pump. In other words, from that moment, she begins to have a mortal life. But if you ask what that experience was for him, it could be seen that her getting rid of air was like a repetition of death. Therefore, he transmits the desire for air to be taken out of her. The love the two feel is a reciprocal one but she receives, she has a body that can receive. But that’s also where she learns about sadness. When I thought about why he asks for such a thing, it’s because he hasn’t had the experience of being filled, so he rushes towards such behavior. But it was hard to convey. What I wanted to show on the bed was the doll attracted to life and the human pulled toward death, .how this was incompatible.

LCE: It’s a profound movie. I think it took courage to make.

HK: I don’t know whether “courage” was involved, but I know it was an extremely difficult topic.

LCE: When I first saw Air Doll I was in Madrid, and the audience there was very enthusiastic. One of my Spanish friends has a question for you. He noted that there aren’t characters with a strong sense of masculinity in your films. Do you think this is an overstatement?

HK: Not at all, he’s right. I can’t write about strong male characters. I’m not interested in authoritarian or paternalistic characters. So I don’t write about them. I can’t write about them. I don’t like them. My own father wasn’t like that, so I don’t have an experience of having a strong father figure.

Air Doll (2009)

LCE: I’d like to ask about the children in your films. They’re often in situations of hardship. Do you think this reflects the reality of contemporary society?

HK: I do think so. This will be difficult to analyze. I was born in 1962; that was after the age of “strong-father” figures. In my generation, we had more family-oriented fathers, but it was different for me. There was no “at home father;” I grew up in an atmosphere of absence. I think it’s the same for children today. The move to revive the strong father figure is an attempt to address issues such as social disorder and disobedience in school that have arisen with the loss of the influence of a strong father. On the other hand, I think it’s important to look at how children have adapted to growing up without a strong paternal influence. In the future, I don’t think there will be a revival of the old-fashioned idea of a household controlled by a strong father (something people like former prefectural governor Ishihara Shintarō have proposed). But I think differently. I’m interested in exploring how children grow and adapt after a guiding authority has been lost.

LCE: When I watched the behind-the-scenes documentary for Still Walking (2008), you said you felt like you became a novelist with that film. You said that the films prior to Still Walking were created more from an observational perspective. I may be mistaken, but can you talk a little bit more about this?

HK: No, you’re not mistaken. Not just in terms of images—even in terms of written language, there are three important points when making something:observation, imagination, memory. To search for memory, one looks back at one’s own actual experiences. In the “Making Of” documentary, I spoke of composing something while balancing the three points. According to the individual work, which of the three becomes central will change. If I speak of the works up to that point, “observation” was the focus. The most important starting point is how to observe. Of course, from that point, I also use imagination.

In Nobody Knows (2004), I overlap my childhood experiences with those of the protagonist Akira. That’s where memory also plays a considerable role. I have continued to use memory and observation when I make films. But with Still Walking—I wrote the screenplay right after my mother’s death—because it was written with elegiac feelings towards my deceased mother. Half of the lines uttered by Kirin Kiki (who played the grandmother) were words my mother had spoken. So how to search for memory, and how to revive my memories of my childhood, makes up 70% of the script of Still Walking. The starting point of that film is from a very private place. Up to that point, I hadn’t thought of myself as an author. I didn’t even like the word “author.” Rather than saying that something arises from within me, I thought: “I encountered someone and in that relationship the work arises.”

This translation was done by Yoshiko Kishi, a Japanese language instructor.

Share: