Ice (1970)

Essay

Ice

On the last gasp of revolution in Robert Kramer’s not-quite-agitprop thriller.

Ice (1970) opens at Metrograph on Sunday, January 18, playing as part of Fugitive Days.

Share:

ROBERT KRAMER’S ICE, ARGUABLY THE signature film of the late-’60s US New Left, charts the early moments of an armed insurrection against the bourgeois American state. Shot like an agitprop documentary in frenzied 16mm black-and-white and set in a vaguely futuristic New York City that looks exactly like its then-present, Ice wastes little time on exposition: the National Committee of Independent Revolutionary Organizations, we are told, has formed alliances with the Black People’s Army and Mexican Revolutionary Front and is now “part of the overall vanguard” against a fascist American government. Its role is to work with “urban white people whose task must be armed struggle.” From there, the film launches into motion, and if first-time viewers struggle to maintain their bearings, that’s precisely Kramer’s intent. He doesn’t want a clean, spoon-fed revolution but rather to steep us in its phenomenological flux. Ice is exhilarating, exhausting, and as concrete a rendition of the psychic landscape of the New Left in 1969—the year it exploded, often quite literally—as any filmmaker made. It was heavily debated at the time, meeting mixed critical reaction, but time has proved it a foundational work of radical film culture.

Watching Ice in 2026, one notes certain affinities with Paul Thomas Anderson’s widely feted One Battle After Another (2025). Though made more than a half century apart, both films are more interested in the political as form than the actual content of ideology, as seen in Anderson’s slogan-level depiction of revolutionaries and Kramer’s deep focus on the structure and process of revolution, which allows him to envision a unified ecumenical movement—one quite unlike the bitter internecine line struggles that would implode the leading Movement organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) shortly after he finished filming in early 1969. Both films, too, are drawn toward the affective layers of radicalism, notably the sense of community it fosters and, conversely, the fraying of social bonds, which the leaders of Kramer’s band of militants navigate as if managerial theories of human capital supersede Leninist theories of revolution. As well, the sexual imbrications of politics—particularly, desire and fear—course through both Battle and Ice, including memorably Kramer’s own character being castrated by reactionaries.

Yet only one of these films aspires to “negate the present in all its forms and build the future.” Anderson opens One Battle with an incendiary raid on an immigrant detention center, but ultimately, he’s a liberal making a film about radicals, resolving matters neatly through familial restoration and a hope for the youth generation wholly unsupported by history. Kramer, in contrast, a dialectician in propagandist’s attire, locks into contradiction and holds us there for two intense, relentless hours. Born into upper-middle-class NYC affluence in 1939 and steeped in a late-’50s alienation at Swarthmore College, he found himself radicalized by the currents of the ’60s and possessed of a split consciousness: skeptical critic and true believer at the same time.

Ice (1970)

Negating the negation is the driving motion of the dialectic, as theorized by Hegel and adopted by Marx, resulting not in a thesis and antithesis that merely cancel one another out (first-order negation) but rather the productive clash that results in a new, elevated synthesis. Ice features an agitprop documentary collective modeled on (and played by) Newsreel, the New Left outfit in which Kramer held a central role, and the film frequently pauses to show their political and experimental shorts; the quote above comes from an intertitle to one such internal film, and it captures Kramer’s intent. He sought to negate the present in all its forms to help construct a more developed next stage of history—but in particular, to negate the left as he knew it. Ice is the rare radical film that denies catharsis specifically to foster an even more revolutionary culture. A snarky Marxist might call it Desperately Seeking Sublation, and it’s precisely that denial of facile closure that makes it a work of left cinema of far more than merely historical interest. It’s less emotionally satisfying than Anderson’s wonderfully made film, but by design.

Kramer’s most brilliant move, his central negation, is the fusing of two wholly incompatible elements: stylistic fervor (the film’s cameraman, Robert Machover, told me his instructions were simply to follow the action) and a hollow, gutted human core. Formally and narratively (to the extent that Ice has a narrative—at the very least, it has a visceral sense of rising action), Kramer essentially runs Gillo Pontecorvo’s landmark revolutionary film The Battle of Algiers (1966) through the documentary tactics of Newsreel. Pontecorvo’s depiction of anticolonial resistance to French occupation was shot with such startling immediacy, the camera seemingly embedded within actual unfolding events, that much of it plays like documentary, even despite opening text for its American release refuting the notion. Newsreel, meanwhile, brought together leftist and experimental filmmakers throughout the US to serve as what scholar Michael Renov calls “the New Left’s own camera-eye on the street and behind the barricades,” shooting from within the Movement maelstrom at the March on the Pentagon, the 1968 occupation of Columbia University, the riotous Democratic National Convention in Chicago that summer, and across the country, as national politics appeared to race toward some sort of rupture.

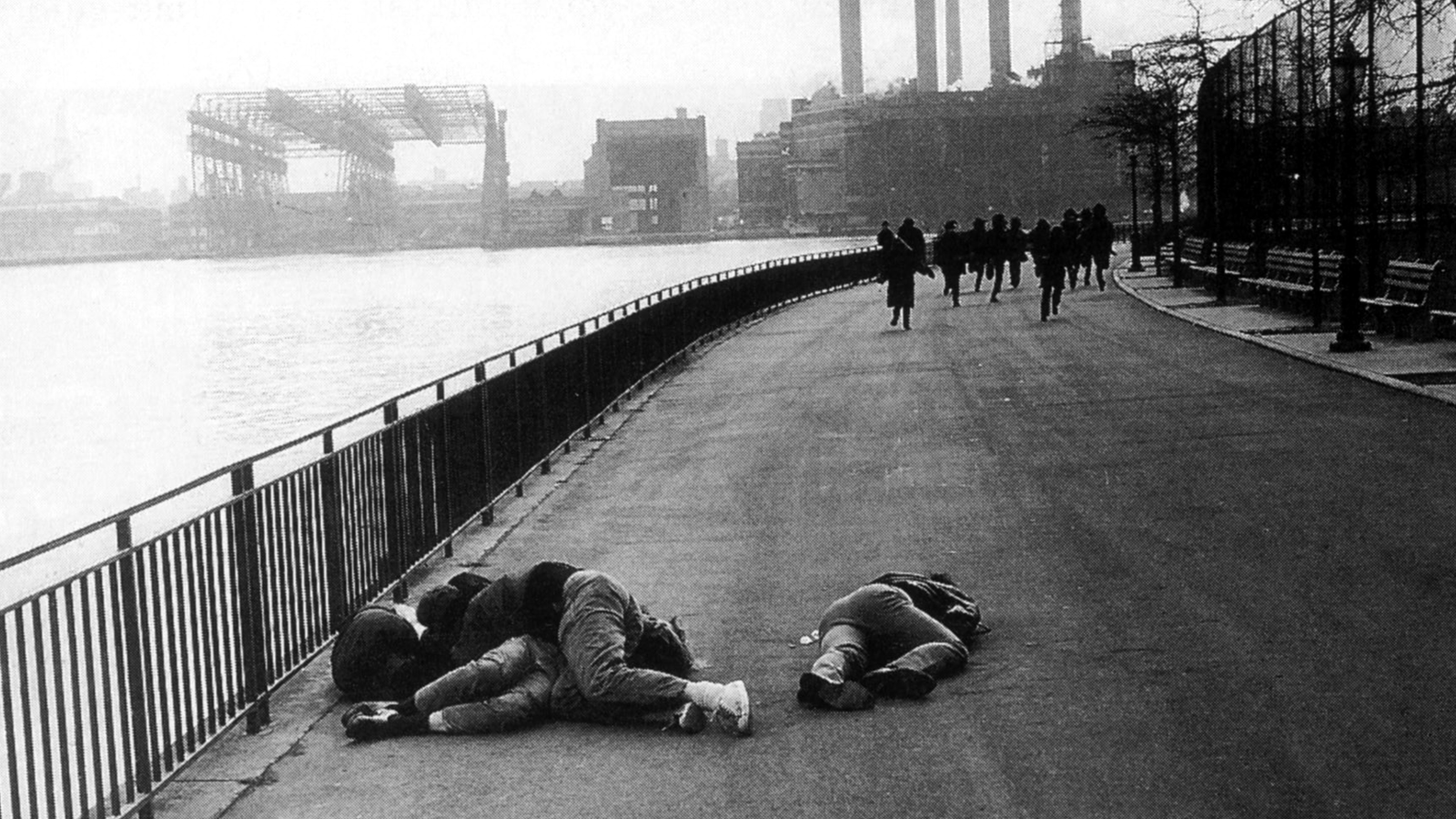

Ice captures the intensity of that moment, probably the last instant in the United States when revolution—at least, a leftist revolution, not a MAGA militia one—actually felt tangible. Kramer shows us the secretive meetings, lengthy consensus-building struggle sessions, conspiratorial handoffs, jailbreaks, assassinations, and shoot-outs. We track a courier as she traverses the city, from Grand Central Terminal to JFK airport, and we get lived-in senses of cold water flats with jazz LPs on shelves, a NYU computer lab, an underground bookstore. It cannot but be rousing; whom amongst us does not desire, at least cinematically/vicariously, the toppling of decadent Babylon?

Ice (1970)

Yet while The Battle of Algiers rallied viewers and filmmakers alike, helping shape the Third Cinema movement that included such anticolonial masterpieces as Argentinian Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas’s Hour of the Furnaces (1968, running four hours but in practice longer because it was designed to include breakout discussion groups), and Bolivian Jorge Sanjinés’s Blood of the Condor (1969, which gave the lie to imperial “humanitarian” agency work), Ice traffics in a far more ambivalent register. Its style is precisely Third Cinema revolutionism, however, Kramer’s characters are less Che Guevara than the zombies from George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968). While events and radical actions elicit heightened affect, the people committing them are trapped in an alienated stupor. This extends themes from Kramer’s first two features, In the Country (1967) and The Edge (1968), which wallow in radical burnout. The first follows an unnamed man and woman as they burrow deep into their own navels after dropping out of the Movement, throwing mutual recriminations around an empty house (it was a bluntly autobiographical take on Kramer’s own brief involvement with SDS community organizing in Newark, as well as his disintegrating marriage). The second feature ups the ante, depicting a young radical who proclaims his plan to assassinate President Lyndon B. Johnson—to a group of comrades so checked out that they mostly shrug it off. For Ice, Kramer won an unlikely Independent Filmmaker Program grant from the American Film Institute (his total budget came out to about $15,600), but even as he traded the Euro-arthouse style that marked Country and Edge for the trappings of contemporaneous radical cinema, he extended the anomie and exhaustion of his earlier efforts. Ice’s big freeze comes not from the violence of state repression, but rather the internal dynamics of the radical cell, where social relations are moribund to the point of collective catatonia.

Thus: agitation and enervation; centrifugal and centripetal pressures in this film that never resolve but only intensify. A couple in bed suffers from blockage as the man worries about sexual torture if captured; various revolutionaries are betrayed and killed; after his castration, Kramer’s own character is shot by paramilitary heavies; and as notes the anguished bookseller and informational relay played by Howard Loeb Babeuf—a onetime beatnik who had edited the League of Militant Poets journal Pa’lante, dedicated to the Cuban revolution and featuring LeRoi Jones, Allen Ginsberg, and passages from an Eisenstein script—no one has the ability to relate to one another. “You’re all so puppet-like,” he bemoans, “so pathetic” and “unfeeling.” He’s a figure of abjection, needy and whiny—and in another Kramer contradiction, perhaps the only emotionally engaged character in the film. Yet for all this, a national revolution is launched. Its status is left unresolved by the film, a Rorschach test thrown back at the viewer: you can plausibly read the events as the stirring first steps of a left ascendance or as a bitter defeatist lament.

Ice (1970)

Only gradually does Kramer’s ultimate negation coalesce into clarity: not of the state nor the status quo—rejection of which was summarily assumed for any audiences in 1969—but rather of the New Left in its then-current form. Ice is an attempt to hail a new, more grounded, organization of the left, to better see through the revolution toward which it only gestures. And Kramer meant this all quite literally. By 1970, he was living in Putney, Vermont, with the Red Clover Collective, a commune that stockpiled guns for a revolution that never came (this would shape his next film, Milestones, released in 1975 and co-directed with fellow Newsreeler and Red Cloverite John Douglas).

Ice itself, meanwhile, experienced its own negation, one that reconfigured its context. It was completed by the summer of 1969 and screened privately for Movement folks, but then wound up frozen in a sustained interregnum. Kramer had imagined it distributed by Newsreel, but its vision of white radicals leading the revolution proved unpopular with the collective. Meanwhile, he departed for North Vietnam with a leftist contingent tasked with returning some POWs and making a film (1969’s People’s War, which he co-directed with Douglas and Norman Fruchter). And back at the AFI, program administrator and scion of Hollywood royalty George Stevens Jr., annoyed by both Kramer’s absence and the film’s politics, effectively disowned it.

Not until Cannes in May 1970, then a booking at the New Yorker Theater that October, would Ice enter public circulation. By that point, it had lost its anticipatory quality; a film set in the future now played as a reflection, as the SDS-faction-turned-breakaway-group the Weather Underground had already commenced the bombing campaign on governmental and corporate buildings that landed it atop the FBI’s Most Wanted list and issued its first communiqué, the very Ice-like “Declaration of a State of War,” in May. Brian De Palma’s anarchic comedy Hi, Mom! premiered in April, featuring an armed co-op invasion that unmistakably parodies a similar scene in Ice—a joke presumably lost on all but hip Movement insiders who had caught private screenings the year before (Kramer was a filmmaker of many strengths but humor was not one of them: in Ice, his invaders round up a number of affluent residents to subject them at gunpoint to Newsreel-like documentaries as a form of mandatory political education; in the hands of the more acerbic De Palma, the gun-toting revolutionaries learn the hard way that the Silent Majority is more heavily armed, paranoid, and violent than any left faction).

Ice proved divisive. From Cannes, Cinema 16 founder Amos Vogel called it “the most important of the American political films,” but a Cineaste dispatch from the radically inclined Pesaro Film Festival berated it as “a Lower East Side wet dream.” In the Village Voice, Jonas Mekas termed it “the most original and most significant American narrative film in two, maybe three years,” but in the New Yorker, Pauline Kael mocked it as “flaccid derivations from Godard,” dismissing Kramer as a “stoned anthropologist.” The most important reception for his own future came from Cahiers du cinéma, then undergoing its own editorial radicalization, which adopted him as the standard-bearer of American left film. By the end of the 1970s, as Kramer faced near-complete neglect in his home country, he departed for France, where although he never again mounted anything as confrontational as Ice, he worked steadily in film and television, mostly on a small scale but not without his epics (the four-hour return to America in Route One/USA, his 1989 masterpiece) and fascinating detours (the 1985 science fiction flop Diesel, his one real attempt at a mainstream crossover).

It takes restraint and confidence to offer up a call to arms as confusing, frustrating, and climax-deprived as Ice. By the rubric of classical Hollywood virtues, a film like One Battle After Another is in every way more satisfying—which is precisely why Ice transcends it as political cinema. Then as now, Kramer’s central contradiction pertains: the left as it exists cannot win; the left if we are to have any future must win. To resolve that on-screen would offer only false hope. Kramer instead hands us this negation, and makes it our job to negate it.

Share: