Interview

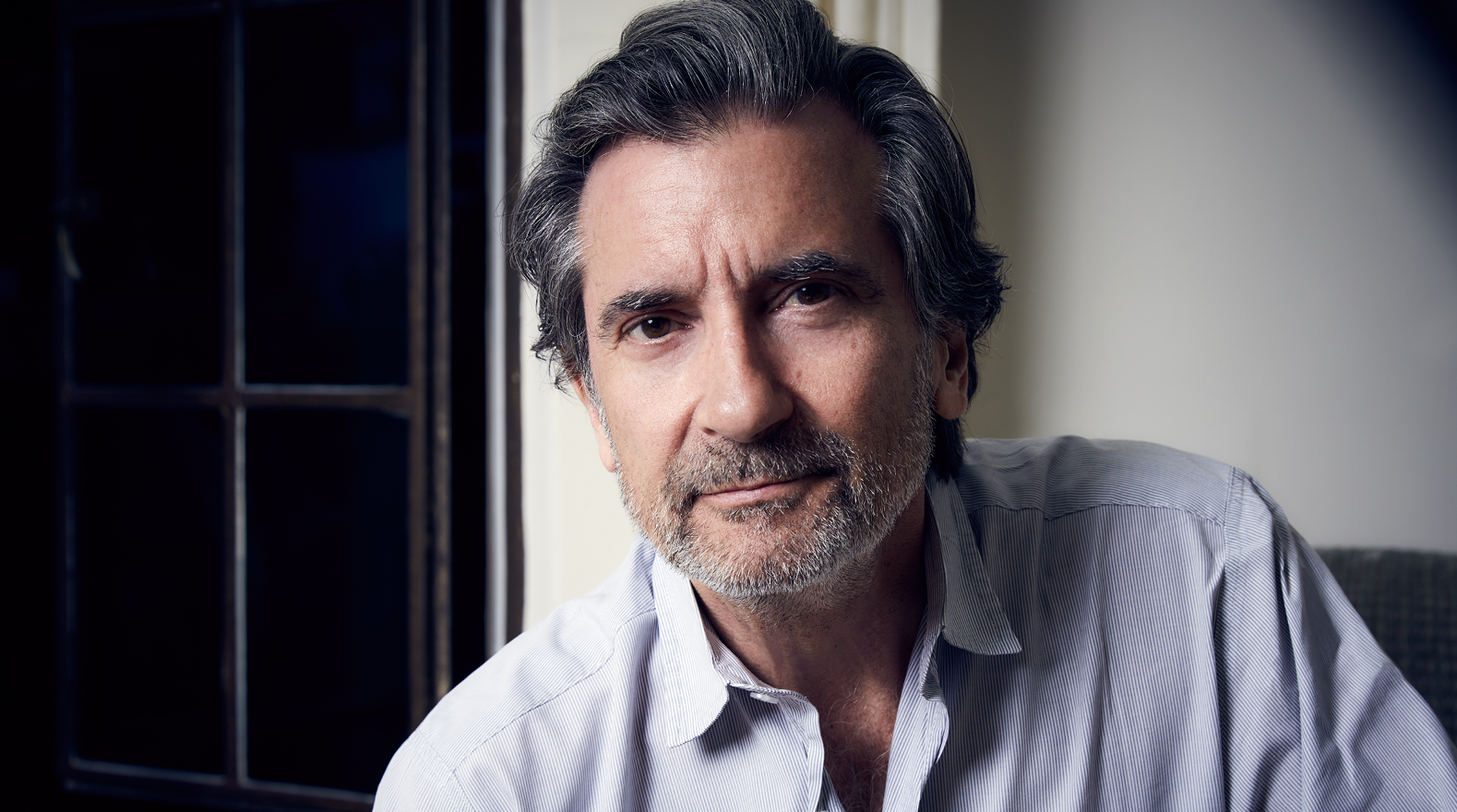

Griffin Dunne

The filmmaker goes behind the scenes of his beloved, witchy fable on generational trauma.

Share:

Before he had turned 30, Griffin Dunne had already produced and starred in a handful of beloved cult classics, even if—by definition—they would not always contemporaneously garner their deserved due. A brief list of his early, auspicious output: he produced and appeared in Joan Micklin Silver’s emotionally intricate breakup drama Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979); two years later, his breakthrough arrived in the seminal horror comedy An American Werewolf in London. And, depending on your age, he is perhaps best remembered as the put-upon data entry worker stranded in Soho on a disastrous New York night out in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985) or as young Vada’s supportive English teacher Mr. Bixler, on whom she nurses a naive crush, in My Girl (1991). For his part, Dunne remains an emotionally dimensional actor (gifted with exquisite comedic timing), who most recently boasts well-received stints on television series This Is Us and Succession.

If Dunne is still admired as an understated character actor, far more neglected is his admirable, sensitive work as a director where one can chart a rare curiosity in (and vivid translation of) women’s interiority. His debut short The Duke of Groove (1995) intriguingly follows a woman (Kate Capshaw) who takes her teenaged son (Tobey Maguire) to a party when his father abandons the family. But Dunne’s career truly took flight with the formidable one-two punch of star-studded romantic comedies Addicted to Love (1997)—with Meg Ryan and Matthew Broderick—and Practical Magic (1998), led by Nicole Kidman and Sandra Bullock as they crested to early zeniths of their respective careers.

Practical Magic—adapted from the Alice Hoffman novel of the same name—in particular has handily claimed hallowed status since its initially lukewarm reception. Bullock and Kidman play Sally and Gillian Owens, two orphans sent to live with their eccentric, bohemian aunts Frances (Stockard Channing) and Jet (Dianne Wiest) after their father and subsequently their mother (from a “broken heart”) die unexpectedly. All the Owens women believe themselves to be cursed (as do their small Massachusetts community where they are reviled), thanks to the heartbreak of an early ancestor: any man who “dared love an Owens woman” would find himself doomed to “an untimely death.” Years later, as grown women, Sally and Gillian cannot seem to escape the grasp of the curse. Sally’s husband dies tragically, leaving Sally and her two young daughters to return to live with Jet and Frances; meanwhile Gillian has fallen for the possessive and violent Jimmy Angelov (Goran Višnjić). When Sally comes to rescue her sister, Jimmy kidnaps them and they fatally poison him. But even in death, his ghost refuses to loosen his grip on Gillian.

Establishment critics originally decried the film for its purportedly incohesive tonal range; and indeed, Practical Magic is all at once a romantic comedy, crime procedural, and horror. (Few comedies and horrors were treated seriously at the time, in any case.) It is testament to Dunne’s craft that the film has burrowed itself into the hearts of women for generations now: for example, actor Paul Rudd, Dunne’s neighbor, once spotted the filmmaker at a restaurant and brought his son’s girlfriend, who was obsessed with the film, over to Dunne’s table just to talk to about the movie. But the authenticity and complexity of its most salient themes, namely the trenchant portrait of domestic violence, is also grimly revealing of Dunne’s own personal experience: his sister Dominique, also an actress, was killed by her boyfriend shortly before her 23rd birthday. Both of the Dunnes were teetering on the edge of career takeoffs at the time of her death.

Even apart from the sincerity, enthusiasm, and sophistication of Practical Magic, one thing that clearly translates is the warmth and energy, which is infectious. Take the infamous, propulsively shot “Midnight Margaritas” sequence; the audience find themselves in the middle of what seems a longstanding ritual. Downstairs Jet and Frances “brew” margaritas, rousing Sally and Gillian until the four women descend into a midnight bacchanal. I spoke with Dunne about shooting that infamous sequence, working with Bullock and Kidman, his aunt, literary luminary Joan Didion, and how the women in his life have shaped all of his projects. —Kelli Weston

Practical Magic (1998)

KELLI WESTON: By the time you signed on to do Practical Magic, you had already directed Addicted to Love; you had produced Chilly Scenes of Winter, in which you also acted…

GRIFFIN DUNNE: That’s how I was finally able to get acting jobs, off that very small part.

KW: It’s incredible the people you were working with: Joan Micklin Silver, Amy Heckerling, Robin Swicord [co-screenwriter of Practical Magic]. I’m curious about what drew you to these stories—cult classics now—which prioritized women’s perspectives and narratives?

GD: You know, people make choices, sometimes without having a clear articulation why; it’s just instinctual. And the thread with many of the projects I’ve taken on is they have always had very strong women in them. My first short film [Duke of Groove] was about a kid going to a party with his mother, but the mother was a really complex character that was loosely based on my own mother. I’m from a family of very strong women: my grandmother was Mexican and she was so tough; she had been stung by so many scorpions, she never even felt the pain anymore. And I had a strong mother and very strong sister, too.

At the time Practical Magic was made, the studios were run by men, and I was characterized as a “woman’s director.” (I’m putting that in quotes.) I was entrusted because, [I had] a certain sensitivity. But the alternate side of that is when the movie came out, critics were mostly men and [the film] was not treated seriously. The emotional complexities of this family [story] that can now be seen as a fable on generational trauma were completely overlooked. It was a novelty that there were so many women in one movie. It was also a novelty to have a studio movie with a pretty big budget [$75 million] headlined by two women. So I don’t think people were quite ready for that at the time.

KW: I know Sandra Bullock brought you onto this project, but had you read the book by Alice Hoffman before?

GD: Yes. Sandy actually saw Duke of Groove in Sundance. We were both there and she really loved it. So I had been on her radar from that moment. But I only read the book after I’d read the script Warner Bros. gave me with Sandy’s blessing.

Practical Magic (1998)

KW: When everything finally came together, you had this incredibly stacked cast: Bullock, Nicole Kidman, Stockard Channing, Dianne Wiest, a young Evan Rachel Wood. And their chemistry is so charming. Did you rehearse a lot? And how did you stage the conditions that allowed for the film’s remarkable naturalism?

GD: Usually, the director sets the tone and work ethic on sets. You could look at some B-roll of the making of Practical Magic, and no matter what was going on, there was a lot of laughter. Sandy is a hilarious person, we would be teasing each other all the time, and Nicole just fell right in. I wanted to convey that playfulness on screen: the back-and-forth and the banter, especially between Dianne and Stockard, both of whom I knew previously. Getting that light-heartedness is actually much harder than the really dramatic scenes, so I would just encourage play. And I felt very much like part of the process. “One of the girls,” I was almost going to say. [Laughs]

When the tone [of the scene] would change, that always excited me, to the frustration of Warner Bros. at the time we were previewing it. The head of the studio said, “Griffin, stick to one tone.” Well, I like two tones. Life has many tones. Fun and frivolity can turn on a dime and become ugly and toxic. And I love those swift changes. I love that there’s this incredible bond between Nicole’s and Sandy’s characters, and the protectiveness [that kicks in] when it comes time to go into the domestic violence involved with Goran’s character. The stronger I made the sisters’ bond and friendship, the more terrifying it was to watch Nicole go through the abuse. It was setting the plate for the actors to be free to go in and out of these complex emotions.

KW: You’ve spoken about the studio interference before. In the face of that, how much of your original vision were you able to preserve?

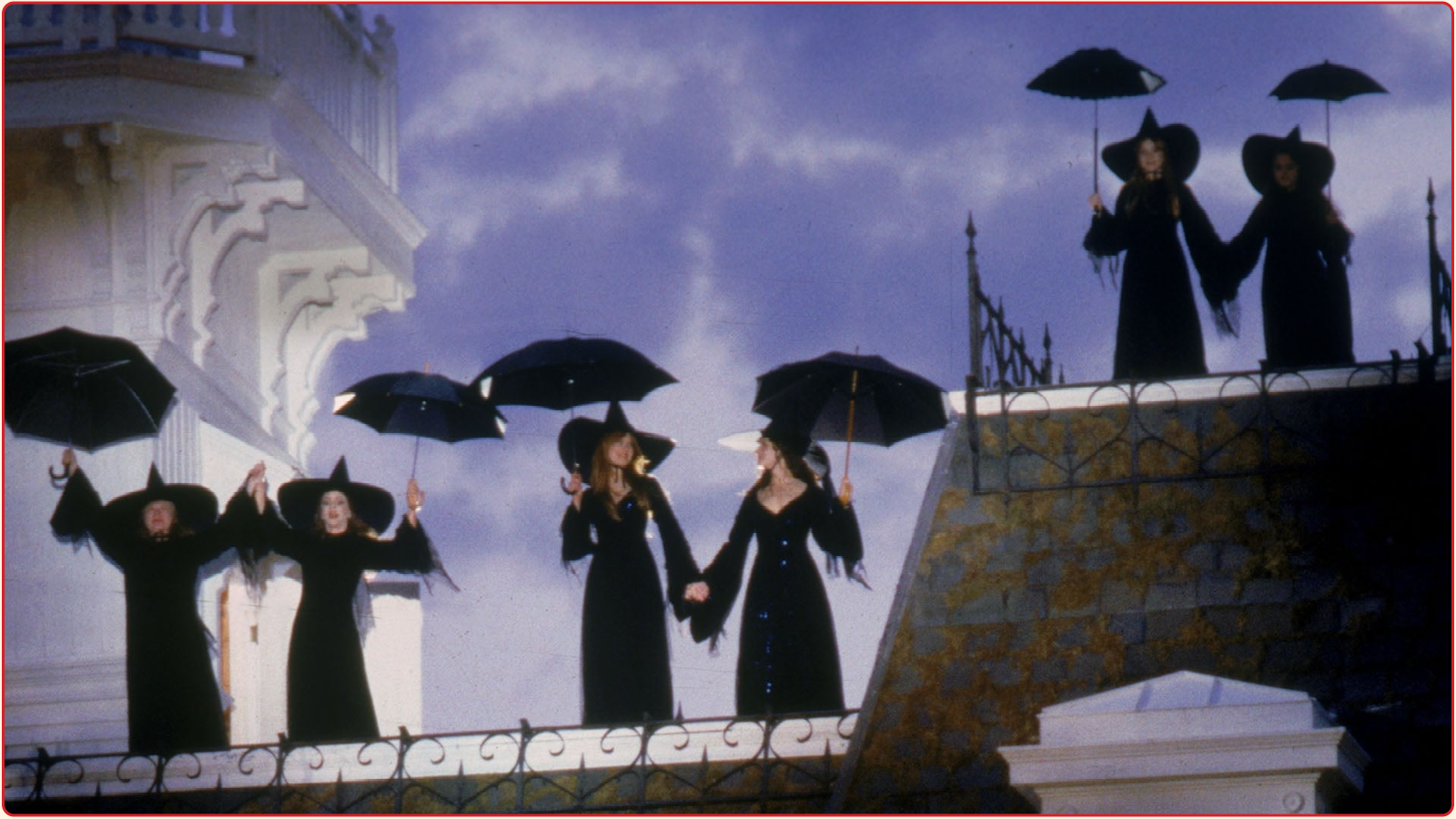

GD: If they’re paying for it, every studio is going to have strong opinions one way or another. During the shoot, I had free reign. It was a big movie, and they gave me enough money to build an entire three-story Victorian house, and then [shoot on] several stages on the Warner Bros. lot, paid well for all the actors, and I got a top-notch crew. So money was never really an issue. And I’m much more familiar with how to make things work with what you have, right? The conflicts came, rather, during the dreaded preview process. For example, the girls jumping off the roof with the umbrellas: that scene had been choreographed, set to music that was quite beautiful. It was uplifting and also kind of abstract. And people loved it in the room, but then others were like, “Why did they jump off the roof?” That’s a logical question. And it doesn’t matter. It was a note that was taken literally [by the studio] and all this sort of second guessing followed.

Then scenes that were terrifying the audience, like the needles being put in Goran’s eyes, that was much rougher [in the original version]. When you’re making a movie with that much money, the studio wants to find a middle ground. They want to raise their hearts a little bit but not send them fleeing. And I guess that one scene did send them fleeing. But nobody quite gets everything they want.

Practical Magic (1998)

KW: I know you said that you weren’t a fan of fantasy when you took on this film, although you had acted in An American Werewolf in London. What were the references, whether literary or cinematic or aesthetic, that shaped your vision of this film?

GD: Yeah, I was really proud of An American Werewolf in London, but [for Practical Magic] the horror and the witchcraft wasn’t what I responded to in the script. It was really the family and the idea of how a curse can be passed down through a family: the way we inherit the dysfunctions and afflictions and beauty and trauma of previous generations. And I understood that very clearly in the script. You know, my idea of horror was that the script was rooted in reality. I understood the terror of domestic violence. It had touched my own family. I found that the more real I made it [in the film], the stronger the more mystical moments became, like Goran’s resurrection. It was just real conflicts between sisters. The more real I made it, it had a wonderful effect on the potions and magic aspects.

KW: You’ve spoken about yourself in the past as an actor’s director. As an actor yourself, you have worked with all these giants: Scorsese, Silver, Robert Redford. And people really love the “Midnight Margaritas” setpiece for good reason, because it’s so well choreographed and shot in a really dynamic way, with the Steadicam winding down the spiral steps. How did you approach that sequence?

GD: From the moment I read the description, I was thinking about how to shoot that scene. I made sure we got the rights to “Coconut.” I told the music supervisor, will you remind [Nilsson] that he sat next to a guy on a plane when he was pretty drunk and he started to scream, “The plane is going down! The plane is going down!” And that was me! But the reason I chose that song, and I told the cast, is I first heard that song when I was 16 years old. It was in a disco, which I was too young to be in. That song came on, and I just became possessed, truly possessed. I started to do this dance and when I looked up while the song was still going, everyone on the dance floor had made a circle around me and erupted in cheers. Then, the bouncer came over and goes, “Can I see your ID?”

That always stuck with me, that possession, so I was always going to use that [song]. I told that story, and then I played this song [for the cast], but it set the tone. It was camera choreographed in that it was, as you said, Steadicam, and then I just let the actors just take over. It was a subliminal direction; I didn’t have to say, “You’re all possessed in this scene.” I conveyed the spirit of the story and it infected everyone. It happened very organically. (I’m leaving out a very key element: Nicole did bring tequila.)

Then, when the tone shift [in the scene] happened, they slid into [that moment] naturally, just like life, where one comment sets off another, and feelings are hurt. People feel under attack, and they attack worse. Being around a bunch of angry drunks was something I was familiar with in life and they nailed it.

KW: I would be remiss if I didn’t say this film is playing at Metrograph in the series My Crazy Uncle (or Aunt), and that your aunt was the inimitable Joan Didion, about whom you directed a wonderful documentary The Center Will Not Hold (2017). It’s this intimate missive to a person you loved, but also to journalism, which you model in the storytelling itself. How did you develop this project and how did you approach her as a subject, both as an icon and as your aunt (who was also famously elusive to her previous would-be biographers)?

GD: Well, at the time, the last book she had written was Blue Nights. Previous to that, The Year of Magical Thinking was about the death of her husband [writer John Gregory Dunne, younger brother to Dunne’s father], and Blue Nights, sadly, is about the death of her daughter, all of which happened within two years. Publishing houses have a promotional video that goes with the book and they’re usually kind of cheesy. Joan had asked Sonny Mehta [editor at Alfred A. Knopf], to ask me to direct the video for Blue Nights. So began this shooting of what turned out to be a short film of Joan getting in the van with a young crew, racing up the St. John the Divine and then going to the botanical gardens. While we’re shooting based on some pretty grim material, about loss and grief, we’re also having a really fun time. And Joan, who wanted to be an actress, really enjoyed being filmed. While having lunch with the crew—who could not believe they were having tuna salad sandwiches with Joan Didion—they just peppered her with questions. You could just see how much fun she was having. That’s when she came alive. It really brought her back to life.

It turned out so well, I wanted to push my luck. Now, many people, as you said, had asked her to do a full-length documentary. Very prominent filmmakers had asked, and she turned them all down. So I was ready for that. I said, “What do you think about me making a feature-length documentary about you?” And she goes, “Umm. Hmm. Okay.” [Laughs] I thought, “I’m going to take that as a yes.”

I originally showed her a three-hour cut, which I knew I wouldn’t use, but I wanted her to see it. She started to see her life unfold and she became profoundly moved. One of the great privileges and the moment I probably am most proud of is when we showed it at the New York Film Festival in Alice Tully Hall—in that high balcony where they have the filmmakers, and the movie ends, and you get hit with a spotlight, and you stand. Writers don’t get to see standing ovations. They don’t get to see their audience thank them for their life work. It was incredible to be looking down at all these people looking up at her. I’m just so grateful I was able to make that moment happen for her.

KW: Please feel free to answer this question as much or as little as you like. You’ve spoken a lot about the profound impact of your sister Dominique’s murder upon your family. One of the things that has made this film more meaningful to me as I have gotten older is that at the core is this story about domestic violence and a woman who is surrounded by love; a woman who survives because of that love. I so appreciate that this is a film about survivors that is also full of joy and warmth and celebration. Do you have a sense of that in the response to this film over the years?

GD: Well, it really was a big part, both consciously and unconsciously. And, you know, I wrote a book that came out this June called The Friday Afternoon Club. It goes into a very dark period, but it’s a memoir about my family, it’s almost an ensemble story. And, of course, it deals with my sister’s murder. There’s a pulse of love that goes all the way through it. We don’t really know what we have until we finish these things. But I did notice that there was a pulse of love that carried me through writing this book, no matter how dark things got. The spine of the film and the book was this thread of familial love that was stronger than all of it. It got our family through it and it got the Owens family through it. I can’t say that was something I thought about every day while making the movie. I only realized when I had my first cut. You know, I’m from a Mexican Irish family, and they bring a certain levity and darkness that are constantly working with each other. That’s a common theme in the movie, and probably in most of the things I get involved with. Those elements are usually in the cauldron.

Practical Magic (1998)

Share: