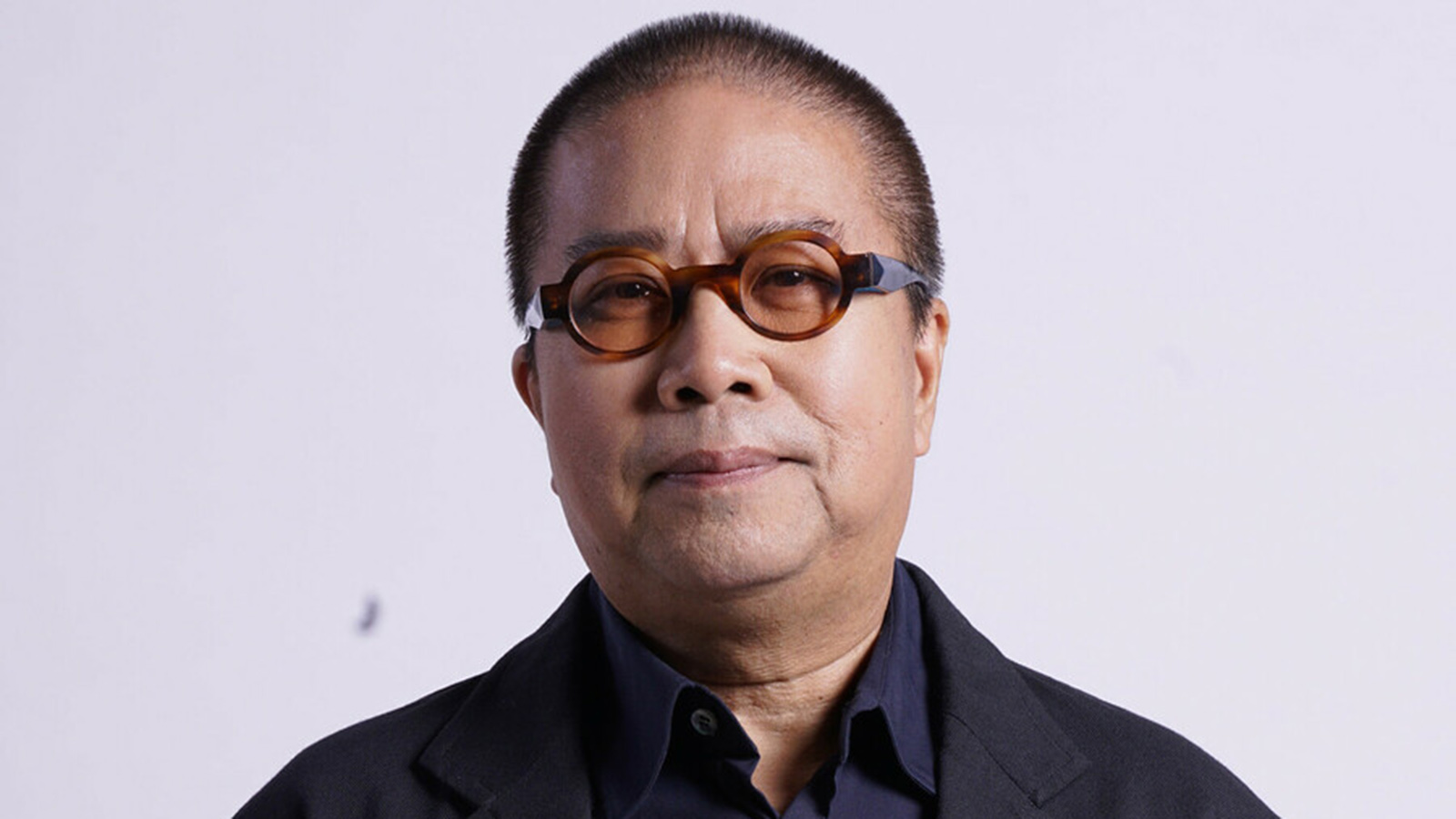

Fruit Chan

Interview

Fruit Chan

Interview

BY

Susanna T.

An interview with director Fruit Chan, from Hong Kong Panorama 97-98, translated by Haymann Lau.

Made in Hong Kong streams on demand on Metrograph At Home via the Metrograph Pictures Library.

Fruit Chan was born in Guangzhou in 1959 and raised in Hong Kong. He entered the film industry in the early ’80s, working as an assistant director. In 1991, he directed his first feature, Finale in Blood. His follow-up, Made in Hong Kong (1997), is the first part of his Handover Trilogy.

Made in Hong Kong has drawn the acclaim of the media and on the international festival circuit. Chan claims that he is not an imagist, but simply someone speaking through images. Chan’s true ambition was to portray a gloomy future through the eyes of a few kids growing up in public housing. Throughout the interview, he emphasized time and again that he is not making a high-sounding “art film,” but crafting with commercial calculations. But Made in Hong Kong is no doubt made with exquisite skill, a statement of its time.

HOW WAS MADE IN HONG KONG CONCEIVED?

Owing to the meagre income and the lack of autonomy, I had not been involved in any directorial role for a few years. In 1995, the year when cinema turned 100 years old, I felt that having assisted so many directors, it was time I made a film for myself! I had just finished a deal with a certain company for a film featuring a fresh new cast. The scene-by-scene shooting script was ready, but the boss changed his mind saying there was no market for that type of film. So I decided to do it without him and carry it on my own shoulders. Then, Andy Lau’s Team Work Production had some 40,000 feet of leftover film stock. So I used it and that’s it. The script which I started writing in late 1995 was about the irresponsible, mean-spirited, devil-may-care attitudes of some young people in Hong Kong. In my research, I found that these young people had nothing in mind for their future, even with 1997 drawing to a close. They had no prospect in life.

THE FILM IS SET IN A PUBLIC HOUSING ESTATE. WHERE DOES YOUR EXPERIENCE OF THAT ENVIRONMENT COME FROM?

I grew up in public housing and spent over 10 years of my life there. I think public housing is a microcosm of Hong Kong society. In Sau Mau Ping or Tze Wan Shan, for example, many youngsters joined the triads. In my mind, the public housing estate is the dark shadow of life. Either you do your best to get out, or your future is hell.

The housing estates that appear in my film now actually look much less morbid and sleazy than what I used to know. When I returned to Kwai Chung for my research, I found that many third-generation young people had already moved out. The majority of those who remained were old people, and the whole place was old and dilapidated. At one point, I was thinking of presenting the developmental history of public housing in Hong Kong, but the idea was dropped to keep the film to an acceptable length. The history of public housing was as bizarre as the development of Hong Kong. The design of public housing is puzzling in that after all these years, its provisions are still no more than the most basic living amenities, with little signs of improvement for the general living conditions.

Limited by production considerations, I was not able to film the lives of the young people in the the open spaces between buildings in the housing estates, but had to confine myself to kids stuck in their flats. But at least I was able to portray three different types of public housing environments: Moon’s home is the kind along a long, dark corridor; Ping’s home is in a building relatively more open, with a huge courtyard in the middle; and finally, where Moon commits suicide, the seven-story old-style buildings in the Kwai Chun area, where you still have several households sharing one toilet. Why are their endings so desperate and tragic? Susan killed herself because she was the kind who could not think and had no solutions for her problems. Ping may have wanted to live, but could not because of her terminal disease. Moon embodies my own experience. He could have lived without committing suicide, but as a response to his contemplation on his love life and his deeds, suicide is a better ending with more a powerful dramatic impact. His pessimistic view of the future is pretty clear.

“IN 1995, THE YEAR WHEN CINEMA TURNED 100 YEARS OLD, I FELT THAT HAVING ASSISTED SO MANY DIRECTORS, IT WAS TIME I MADE A FILM FOR MYSELF!”

YOU HAVE CAST PEOPLE OF ALL AGES WHO ARE NOT PROFESSIONAL ACTORS. ARE THEIR PERFORMANCES SATISFACTORY TO YOU?

Time was very important. I spent two months rehearsing with them. In the beginning, they could not even read the lines, but with more rehearsal time, they gradually managed to enhance the script with their own views and voices. Especially for the older actors, who could only come to the shooting after a whole day’s work, acting with dialogue was already difficult enough, plus many of the scenes required the injection of inner feelings and intense emotions. As a result, the older actors were more prone to mistakes.

The problem with nonprofessional actors is that they are rather reserved in general. Perhaps it’s something very Chinese: it’s very hard to get them relaxed for certain scenes. The bed scene with the two protagonists, for example, had been rehearsed for two months, and still, it was not as natural as I wanted.

THERE WERE ONLY FIVE PEOPLE IN THE CREW. HOW DID YOU MANAGE?

I was basically the driver. Only at some rare moments could we gather all five of them. Most of the time, there were, including myself, only three or four of us working on the set. Fortunately, we were a very professional team. Whoever had no part in the scene would take care of audio recording, and when we were shooting in the hospital, I even painted the walls!

DID SHOOTING LIVE UP TO YOUR EXPECTATIONS?

I should say that in terms of editing, I managed to cut the film into a coherent piece. What could I have done? I already cut out many of the scenes that were not well acted. In the original script, I did not have any voice over narration, but they were later added to scenes where the acting was not competent enough. If I were to give myself a score, I would say 70, and that mainly goes to post-production.

CAN YOU EXPLAIN THE CASTING FOR THE TWO MAIN ROLES?

I picked them for their looks, which quite matched the characters, rather than their acting capacity. Sam Lee is an electrician. When I first met him, he was speeding on his skateboard on the basketball court. He was skinny and came across as a gangster kid. But he’s actually quite different: he’s 21, has no interest in comic books, but has a good fashion sense. Neiky Yim is from a single-parent family. She was still a fourth-form student when I cast her. She’s also interested in fashion, but of the very quiet type. They’re both very different from the roles they play, and in a way they have given life to their characters through their performances.

This interview first appeared in Hong Kong Panorama 97-98. Special thanks to the Hong Kong Film Festival for giving us permission to reprint this piece.