Interview

Deborah Stratman

An interview with the experimental filmmaker about her newest film envisioning life on Earth from the perspective of rocks.

Share:

Life was born from rocks. Last Things (2023), filmmaker Deborah Stratman’s kaleidoscopic, epoch-sweeping, sci-fi-tinted visual essay, put me back in touch with the awe of that fact. Minerals, despite their mysterious not-living status, gave rise to the first life! That biological vivaciousness could emerge from the chemistry and energy of unmoving, unliving material seems improbable, but it’s true. Minerals can also evolve, according to a theory of mineral evolution surfaced by the film; one of many shards of ideas served up that, for an intoxicating hour, blurred my sense of taxonomy and bio-centricity. Rocks are perhaps the original ancestors. What would a history of the universe look like from their perspective? Maybe it would look like Last Things.

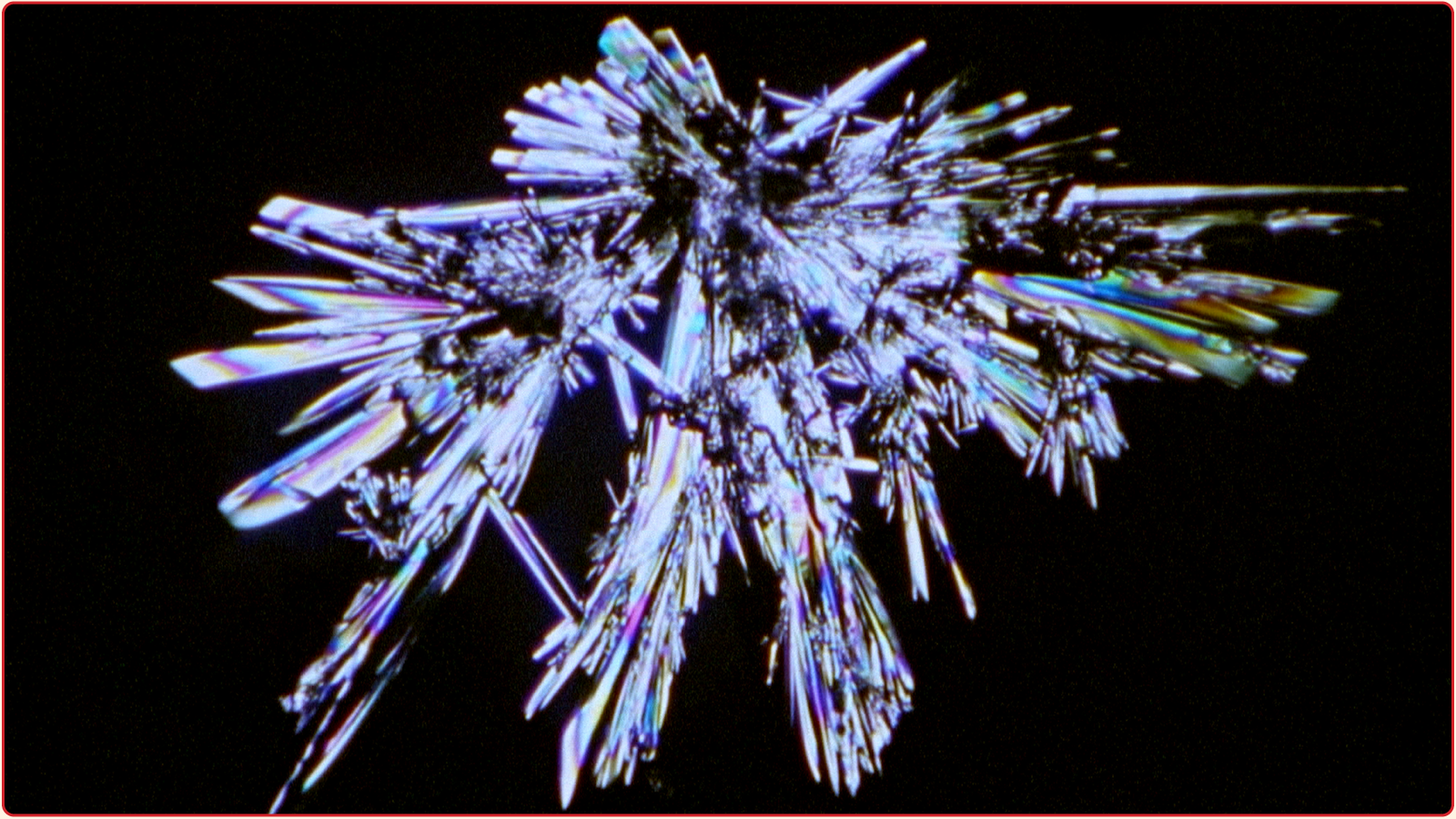

The film is a flickering bouquet of sounds and images—algae cells tumbling under a microscope, drawings of the whimsical geometric architecture of minerals, shots of the rock architecture of Petra, diagrams of the Earth with its magnetosphere bristling out from the poles. Snips of haunting French science fiction about sentient crystal beings set a mood of rock-supremacy. These and other voices are matched with the steady, curious narration of a preeminent geologist with a deferential awe toward her study subjects. “Chondrites are the old ones,” she says, referring to extraterrestrial rocks that arrived to Earth as meteorites. Even our own bodies do not escape the mineralizing lens: Mitochondria, the little organelles in our own cells that allow us to use oxygen to power our own metabolism, are a “geologic memory in all our cells.” Eons of geologic history collapse into the present.

When I first saw this film, in January, I staggered away with a head full of ideas. If geology can hold this much artfulness, can teach me this much about time, what other parts of the universe had I overlooked? I’d recently written a book about the potential for intelligence in plant life. But perhaps I had failed to look far enough afield. I already thought the lines we draw in the sand (more minerals) between so called “animate” and “inanimate” life were somewhat dubious for not including all biological life. But what about mineral life? Categories shimmer, hierarchies falter, human timescales feel altogether trivial. And here I am, nearly a year later, still ensorcelled by the existential feelings Last Things brought up. Over email, I exchanged questions with Stratman. —Zoë Schlanger

ZOË SCHLANGER: Rocks are the main characters in this film. What intrigues you about them, and what animates them for you? Magnets and microbes seem like supporting characters. What, if anything, ties all three together?

DEBORAH STRATMAN: I like that if you put a rock in your pocket, you’re carrying around an ancient being, utterly alien, but so unobtrusive. Magnets are the sorcerers of the mineral world. Microbes wouldn’t be around without the Earth’s churning molten iron core. That dynamo creates our magnetosphere, the protective field around our planet that shields us from the solar winds that would otherwise annihilate life.

Last Things (2023)

ZS: You seem drawn to the vibrancy of things which are not quite alive—the ways that rocks can evolve, for example. It reminds me of theorist Jane Bennet’s idea of vibrancy, which she uses to talk about the liveliness of nonhuman and sometimes nonliving things, things we would ordinarily consider objects, and not subjects. In Vibrant Matter, she writes that humans are too seriously engaged with the odd hobby of drawing lines in the sand between subjects and objects: “The philosophical project of naming where subjectivity begins and ends is too often bound up with fantasies of a human uniqueness.” Do you think rocks and microbes and elements toe this line of subjectivity? Do you think geologic formations have a form of subjectivity, so to speak? Does the magnetosphere? If subjectivity is not the right word, what would be better?

DS: I’m not sure what the right word would be, nor where subjectivity’s edges are. I’m into thinking about thresholds though. Between backstage and onstage. Between the person and the character. Index and fable. Sound and music. Waking and sleeping. Money world and non-money world. The edge between you and not-you is a big one. Or we make it so, maybe to our psycho-ecological detriment. If subject/object wasn’t an edge, we’d be less prone to relationships of ownership, mastery, commodification. They’d skew more towards kinship, responsibility, respect. Luckily for the rocks, as Eliot Weinberger says, they’ve drifted from their names. They’re unindentured to our naming project.

ZS: You open the film with a Clarice Lispector quote from her novel The Hour of the Star. I love this quote, about how all the world “began with a yes. One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born.” Lispector’s ecological thinking is so piercing throughout all her work. Why start there, what power does her thinking hold for you?

DS: Reading Lispector is like getting prescription glasses after having lived without them. A layer of haze lifts. Her thinking is so visceral. Existential, feminist, stubborn, agonizing, uncanny. She leans into the void. It’s a sort of clairvoyance, a spell casting, a set of little pointed teeth. Lispector, or maybe someone writing about her, said she wants to see “what’s behind the back of thought.”

Lispector was Brazilian, and coincidentally, the film also ends there. I shot the street dancers in Belo Horizonte 15 or 20 years before the idea for this film existed. The physicality and attunement of that handheld sequence which was edited in-camera, falling where it does at the end of an otherwise pretty static film, is a scale-collapsing rejoinder to Lispector’s words. Each is a sort of vertical stake, like two pins the film gapes between.

Last Things (2023)

ZS: I’m interested in the quality of collage that this film has, or rather it feels like veil painting: all these fragments and layers and gestures assembled until an entirely new entity emerges. I saw you describe yourself as a “quotationist” in another interview, which I love. I’m curious about your process, in terms of gathering all these pieces of disparate media and references. Does it happen in archive-combing bursts? Or slowly, an accretion? What threads did you follow to find the parts of this film?

DS: I’d never heard of veil painting. I just read that it’s Rudolf Steiner–inspired and assigned in Waldorf 10th grade. I like the transparency that the veil analogy adds to stratigraphy. And I dig a palimpsest, especially if it’s shape-shifting. My gathering looks different for each film, but I’m essentially a gleaner. A quotationist of words, but also non-words, sounds; every shot my camera and I take is a quotation of a place in time. Last Things is particularly sample heavy—a mixed product of working during Covid, being dug-in to the studio, and the natural progression of a heap of reading and archive trolling. I kept being bowled over by things I would learn about, and each new thing pivots the future film shape.

One thing the gathering looks like is piles of index cards, some with drawings, some with words, each a distillation of something I’ve read or viewed or heard or shot. I shuffle through them, pinning them up on a big corkboard in different orders. Each card represents a concept or cinematic phrase. Having them on cards is a quick way to sketch out different structures. But I can’t rely on them too much because at least half the time a sequence that looks great on the board fails as cinema. It’s a lot of trial and error, working with the rhythms and pressures and skeins of the timeline. In my filmmaking, everything is editing, from deciding what will be outside the frame to the vertical congruences of sound-image.

ZS: You chose to call this film Last Things, when in many ways it feels like a film dealing with first things—with the role of minerals on the early planet, and with the dawn of biotic life; with the idea that all life can ultimately be traced to minerals interacting with water and carbon dioxide, as I believe a scientist in your film puts it. Then again, the whole film is engaging with a theory of nonlinear time, as told through the polytemporal nature of geologic formations: how they are a living memory of deep time but how they also exist now, in our world, and in some sense in us, as a product of them. Could you tell me more about the title and what it says about time? I’d love to hear what your theory is about how time works.

DS: Time is a collaborator. We pattern one another. I’ve thought about it as an idea that will die out in the mind. As one of an infinite number of paths through a field of all possible events. As a constantly recycling donut, where time is the glazed surface, sliding inwards towards the donut hole and back up the outside of the torus. As a resonating chord, like on a guitar, where birth and death are like two pressed notes, between which life vibrates. I’ve thought about what we do with time—waste it, spend it, slow it, speed it, avoid it, kill it, do it, tell it, change it, travel it, sleep through it—and what time does with us: ages us, articulates us, erodes, renews, entwines, destroys, amplifies, recycles, holds, transfigures. William Burroughs called humans the “time-binding” animal because of our ability to communicate through writing into a future beyond our own lifespan. Though for him language was also a virus, so I’m not sure if he’d consider the time-binding parasitic or endemic.

I strongly connect to [structural geologist] Marcia Bjørnerud’s advocacy for polytemporality and timefulness. The title is meant to be a tease, because the film is as much about evolution and appearance as it is about extinction and disappearance.

Last Things (2023)

ZS: How much do you love science fiction?

DS: So much. Cognition + estrangement. Amen to the generative, critical, sociopolitical, speculative genius of these folks. Hello Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler, Joanna Russ, J.G. Ballard, N.K. Jemisin, Amos Tutuola, Renee Gladman, James Tiptree Jr., Samuel Delany, Hiromi Kawakami, J.H. Rosny… Cognition + estrangement is what I love about documentary too, or at least some kinds of documentary, like the kind of estrangement called ethnography, a form which is as messed up as it is vital. With Last Things I’m disoriented and thinking-into as a non-geologist making a film about, with, through rocks.

ZS: What is one scientific mystery you would most like solved in your lifetime, purely to sate a curiosity?

DS: Ball lightning. Actually, it’s not that I want it solved. I just want an encounter.

ZS: The sounds in this film are a world unto themselves. I particularly love the watery squidging noises that play while we’re watching fat green volvox algae roll around. What are you listening to these days (music, field samples, etc.)? And what is your favorite noise?

DS: I don’t have a favorite. Today’s listening included some birds, distant trains, an aeolian harp, BBC Radio, Noga Erez, Einstürzende Neubauten’s “Nnnaaammm,” which we’re singing in choir, Moondog (ditto), Ibelisse Guardia Ferragutti and Frank Rosaly, Iri Di, The Fall, Junior Kimbrough, Kate Bush, and two cool recordings that Samar Al Summary played for me of a Bedouin chant and a pair of riffing coyotes. My partner and I are building a large VLF natural radio antenna/induction loop transformer, so we have been listening to the ionosphere. I’m into the Schumann cavity and the resonant habits of the magnetosphere. It’s a giant concentric air gong up there with lightning strikes as the mallet. Like Pauline Oliveros says, “The waves are out there and they’re waving.”

Last Things (2023)

Share: