Cracked Actor

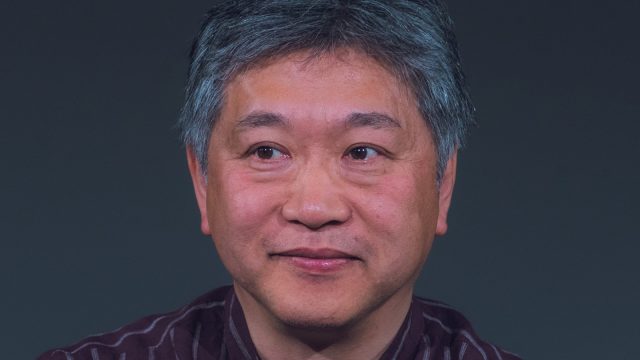

Bae Doona

On the eclectic career of the mesmerizing actress.

Doona, Doona, Doona plays at Metrograph from Friday, December 12.

Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000)

Share:

IT’S HARD TO THINK OF a Korean actor who is as enigmatic as Bae Doona. Her oeuvre spans numerous countries and languages; she nimbly moves across different contexts, from Korea to Hollywood, English to Japanese, playing an unemployed anarchist with as much conviction as a lesbian cop. Sometimes, I struggle to reconcile the multiple strains that run through her expansive body of work: the international star, the arthouse darling, the action heroine, the runway model, and even an amateur photographer. (Between 2006 and 2008, she published three photography books, each focusing on the urban landscapes of London, Tokyo, and Seoul.) Now aged 46, with some three decades in the industry, Bae has grown into a singular screen presence. In the anglophone world, she is likely most recognized for her collaborations with the Wachowskis in Cloud Atlas (2012), Jupiter Ascending (2015), and the Netflix series Sense 8, and more recently with Zack Snyder in the space epic Rebel Moon (2023). But in her home country, many still see her as an unconventional star who continues to work in smaller arthouse films such as A Girl at My Door (2014), Broker (2022), and Next Sohee (2023).

Curiously enough, Bae may never have acted at all. Although exposed to the world of theater at a young age by her thespian mother, she was a shy kid whose early experiences around prominent theater artists had the unintended effect of scaring her away from the profession. Instead, she became a model. Bae burst onto the Korean fashion scene as an “It Girl”—not unlike her contemporary Kim Minhee—with impeccable style in the late ’90s, appearing on the covers of Harper’s Bazaar Korea and Marie Claire Korea. In 1999, Bae made her screen debut in the immensely popular teen drama television series School (the following year, Kim would star in its sequel School 2). Apart from their shared love of Lemaire, both would go on to become two of the more acclaimed Korean actresses with international recognition, albeit with some crucial distinctions. Before Hong Sangsoo’s Right Now, Wrong Then (2015) and Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden (2016), Kim was frequently typecast as a beguiling femme fatale. These days, her name is synonymous with Hong’s beautiful late-period cinema (and indeed the public scandal of their affair has perhaps made it difficult for her to work with anyone else). Bae, on the other hand, found success rather quickly, in arthouse fare as much as blockbusters. The same year she appeared in School, she would star in The Ring Virus, the Korean adaptation of The Ring (1998), as the counterpart to the vengeful ghost child Sadako Yamamura. This initiated an impeccable run, followed by Bong Joon Ho’s Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), Jeong Jae-eun’s Take Care of My Cat (2001), Park Chan-wook’s Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002), and reunited with Bong for The Host (2006), which was at the time the highest-grossing Korean film.

Early in her career, she was often referred to as “alien girl” due to her strikingly big eyes, pageboy haircut, and deadpan expressions. Further fueling the mystique surrounding the actress is how protective she is of her privacy (her past relationship with Cloud Atlas co-star Jim Sturgess remains a rare glimpse into her life outside of the silver screen). No wonder Bae has endured as a generational icon for countless Korean millennial women, myself included, who project onto her images of their own desires and sorrows: growing pains, love for friends, and the weight of misogyny. It is likely this same mysterious aura that has also intrigued major auteurs like Bong, Park, and Hirokazu Kore-eda.

Air Doll (2009)

Although Bae was omnivorous in her choice of projects in the early aughts, she proved herself to be especially adept at playing dreamers: whether a revolutionary anarchist in Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance or a delusional romantic in love with a man who leaves a cryptic note in a library book in Spring Bears Love (2003). One of the defining roles of her filmography is Tae-hee, a 19-year-old girl who fantasizes about leaving her patriarchal family and motherland from Take Care of My Cat. In her booklet essay included in the film’s 20th anniversary dossier, the actress calls the character “maybe a daydreamer, probably a wanderer.” Caught between a toxic family dynamic in which her parents show blatant favoritism toward the son and a disintegrating high school friend group due to economic precarity, Tae-hee yearns for a nomadic life on a boat, devouring books while adrift in a river. Her escapism notwithstanding, she is the only one in the group to truly show up for a friend who ends up in a juvenile detention center. Bae attributes her remarkably assured performance to the fact that Tae-hee is a character who resembles her the most. Her desire and devotion to friendship instantly established Bae as a mirror image of millennial womanhood in Korea, who also sought a reprieve from South Korea’s pervasive misogyny and neoliberal consolidation triggered by the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

My first encounter with the actress was in 2006, at age 13, when I saw Spring Bears Love and Take Care of My Cat almost back to back. Aside from the Christmas-red mittens and blue sweater Bae wears in the films, which I begged my mother for, it was the shots of Bae lost in books that really spoke to me. All of a sudden, reading looked impossibly cool, and I started frequenting my local library and bookstores, sometimes feigning illness to cut school to do so. Quite a few of my peers have stories like this about Bae: getting her pageboy haircut only to regret it immediately afterwards; adapting Tae-hee’s words—“I’d still believe in you even if you committed an axe murder”—as a mantra about friendship; a lifelong nicotine addiction prompted by the image of Bae smoking in bed. When I first read Susan Sontag’s essay “The Decay of Cinema,” wherein she argues that movies, at their height as a dominant artform, taught people how to live, the closest analogous example I could think of was Bae. Indeed, for some of us, she was a walking lifestyle guide, and her oeuvre a Bildungsroman through which we hoped to grow with and like her.

What continues to make Bae and her filmography aspirational is her persistence, both in and out of character. She seems drawn to roles that require a certain athleticism, for over the years she has trained in archery, volleyball, table tennis, and martial arts. While not muscular in build, Bae moves with astonishing agility and grace, which no doubt helped her break onto the international stage. Even when playing opposite the action heroine of Korean cinema, Ha Ji-won, in the ping-pong drama As One (2012)—during which Bae seriously injured her left shoulder and foot—she holds her own. However, she truly excels when her strengths as a physical actor are employed in the service of playing clumsy first attempts or moments of hesitation—a quality uniquely suited for Bong’s cinema of “piksari,” a Korean word for ridiculous mistakes. In her first confrontation with a fleeing puppy killer in Barking Dogs Never Bite, she runs into a door and gets knocked out; in the role of a William Tell-like archer in The Host, her anxiety gets the best of her and she fails to shoot arrows. Yet, as the old saying goes, failure is the mother of success. So she persists until she gets it right. When the nervous archer, after all the missed opportunities, finally deals a lethal blow to an amphibious monster, this moment feels as much like the birth of a Bongian hero as a call to perseverance.

Take Care of My Cat (2001)

Bae brings her heroic resolve into a character facing a more quotidian, but no less daunting challenge in Linda Linda Linda (2005), her first project outside of Korea. A coming-of-age musical drama set at a Japanese high school, the film follows a band of four schoolgirls dealing with a last-minute line-up change just three days before a show. Out of impulse, the band’s keyboardist Kei (Yuu Kashii) ditches the keyboard for the guitar, an instrument she is unfamiliar with, and recruits Son (Bae), a foreign exchange student who can barely speak Japanese, as a new singer. From then on, the girls rehearse songs from the Japanese punk legend The Blue Hearts. Despite the language barrier, Son quickly gets the hang of the Japanese lyrics, and Kei’s guitar-playing, dismal at first, improves significantly over the course of the film. The reserved, aloof Son, with her offbeat sense of humor lost in translation, is a perfect match for Bae who operates in the realm of opacity. Son mostly listens to other people, and when she cobbles together rudimentary Japanese sentences, the wooden line delivery often rhymes with her stiff postures and movements. The wide, unblinking eyes and repetitive nodding are her primary modes of communication, whether it’s small talk with Kei at a bus stop or an awkward attempt at rejecting a boy who confesses his love in barely comprehensible Korean. But Bae’s innate agility returns in one of the film’s most memorable scenes: Son delivers a Korean monologue in an empty auditorium, introducing her bandmates with her humorous impressions of them to an imaginary audience. Her voice, now melodic and marked with much more fluidity and grace, reveals a version of her that has hitherto been a mystery to other characters. It is often said that multilingualism brings out different personalities; and underneath the amusing soliloquy lies a poignant realization that the rest of the band may never get to meet this Son. But through music, they share a bond that bypasses verbal language.

The delayed Korean release of Linda Linda Linda came amid rising territorial tension between South Korea and Japan over the Liancourt Rocks in 2006. As a result, the film received unexpected political attention, with some contemporary Korean reviews commenting on the friendship between Son and her Japanese classmates, seemingly unburdened by the history of Japanese imperialism in the peninsula. Given the Japanese government’s refusal to formally apologize for its colonial atrocities in any meaningful way, perhaps the film is naive to a fault in its depiction of their dynamic. But in Kei’s dream sequence, in which she and Son converse in their respective mother tongues and perfectly understand each other, I see a thoughtfully considered utopian future for the two countries, instead of historical revisionism. Son addresses Kei as her “comrade” in the same scene, recognizing their commonalities as East Asian girls with a shared passion for music. Coming two years after a total lifting of the ban on Japanese media in South Korea, Linda Linda Linda felt like a vision of the world my generation could work toward, and Son unwittingly became the patron saint of transnational solidarity.

In a 2019 interview with critic Baek Eun-ha, Bae shares her artistic philosophy: “I don’t like it when an actor explains too much in their performance … I trust that the audience will use their imagination to fill in the gaps.” Her opacity stems from her conviction in the viewer’s emotional intelligence. She understands that a performance can derive its potency through a collaboration with the audience who project onto a character their own experiences. Bae’s subtle facial expressions and understated gestures, then, are a result of a delicate balancing act between articulation and concealment. It is what she deliberately leaves out that speaks directly to our imagination.

Share: