Interview

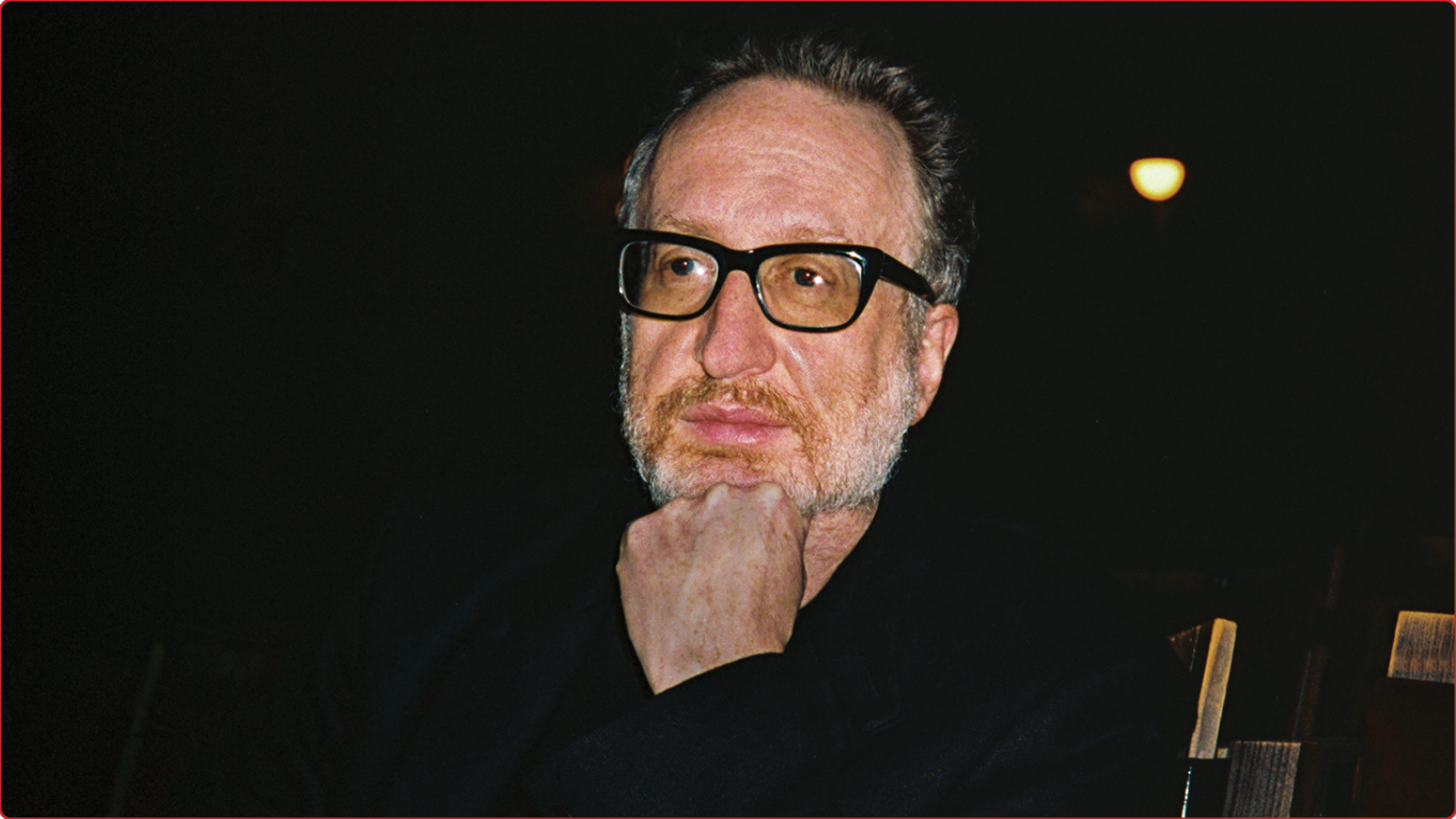

James Gray

James Gray discusses Armageddon Time, how a great many things happening in the world and to his body are Very Bad, but the paintings of Édouard Vuillard, the films of William Wellman, and a nice burger are Very Good.

Share:

I sat down for dinner with James Gray in the Metrograph Commissary on the eve of the midterm elections, which he was convinced weren’t going to go well, and we talked about how not much of anything in the world seemed to be going well, and about old movies, and about his new movie, which bears a title appropriate to our age: Armageddon Time.

Gray, with this film, had returned to shoot a story set in his native New York City for the first time since 2013’s The Immigrant, likewise gorgeously photographed by DP Darius Khondji. Armageddon Time is another period piece, but one that depicts a period—and a sequence of events—that Gray witnessed firsthand, set on the eve of the Reagan election. Describing a series of incidents in the life of a 12-year-old Jewish boy living in Queens, played by newcomer Banks Repeta—in particular his relationship with his disapproving parents (Anne Hathaway and Jeremy Strong) and his disapproved-of relationship with a Black classmate (Jaylin Webb)—Armageddon Time might be described as a coming-of-age story. As such, it doesn’t reflect particularly flatteringly on the meaning of adulthood as it was coming to be defined in the United States at the beginning of the 1980s, as the humane, mensch model of values represented by the boy’s grandfather (a superb Anthony Hopkins) has begun to give way to a much more rapacious self-interest, represented by a certain rising dynasty of Queens real-estate millionaires.

While waiting for the impending apocalypse—and Gray’s scheduled appearance at an uptown DGA screening—we ordered our drinks and started in.—Nick Pinkerton

JAMES GRAY: I’ve been so sad about what’s happened with movies. But you know, it’s interesting, I need to stop reading about it, but I’m a little bit of a political junkie, and you know, nobody’s showing up on the Democratic side today, it’s going to be a catastrophe. And maybe this is connected to some kind of megalomania, but I’ve started just thinking, “That’s it, man.” It’s the moment where anybody with anything interesting to think about or anything has just tuned out. Just doesn’t leave the couch. Doesn’t vote. Doesn’t go to the theatre. Just stays at home. I don’t know what they do.

NICK PINKERTON: Podcasts are a thing that have some importance in people’s lives, apparently?

JG: I’m totally ignorant. I have to do a podcast on the 21st. A guy named Marc Maron. I’m like, “I don’t ever listen to podcasts.”

NP: Nor myself.

JG: You know what I love? Silence. I sit in the dark in silence a lot of nights, which my wife thinks is a little strange. But the kids go to bed, my wife goes to bed. If I can, I watch a movie, an old movie usually. And then, I come back into the house. I love how quiet it is and how dark it is. Two minutes, just sit there. It’s been very restorative.

NP: I recall, and I’m definitely paraphrasing, a bit from James Ellroy where he’s describing how he spends his time, and he says, “I just a lie in a dark room and think about women I’ve known.” Maybe it’s from one of his novels, actually.

JG: Really? Well, I’m not thinking about women. Usually I try to make my mind as blank as possible. It’s not easy to do. It’s very hard. You sort of picture yourself in a movie theatre. And the minute an image comes on the screen, you wipe it off, so it’s blank. It’s very difficult to do. It’s sort of what’s supposedly achieved with the mantra.

[Food orders are taken; Mr. Gray gets a medium rare burger with salad; Mr. Pinkerton a medium rare burger with fries]

JG: So how does any repertory theatre survive today? I don’t understand this.

NP: It’s interesting what seems to take off. What I’ve observed with, let’s say, more “challenging” fare that has been very successful in the last few years is that it tends to be things with somewhat epic scope. For example, Kino Lorber did I think five or six Miklós Jancsó restorations. These were hot items when they played here. And I don’t know if you had occasion to see Aleksei German’s last movie, Hard to Be a God (2013), but that was very successful when it played Anthology Film Archives. It’s this three-hour movie set in a mud-drenched mediaeval Russian village straight out of Breughel, but it feels big and, for lack of a better word, distinctly cinematic. And it seems like people, when they’re deciding “Am I going to watch it at home, or am I going to go out to the theatre?” the tiebreaker is that element of spectacle that makes them say, “Oh, I have to see this on the big screen.” And I don’t know exactly how to feel about that. Because a great deal of the cinema that’s very important to me is very small, very intimate, it’s watercolors rather than the big blockbuster canvases. Visconti at Lincoln Center was another retro that did gangbusters. And that awful Sergei Bondarchuk adaptation of War & Peace (1965-67).

JG: Let me ask you a question. Have you ever been to the Louvre?

NP: I have.

JG: So you got room after room of mediocre genius. Huge canvases, these Davidian battle scenes that don’t mean anything to anybody. And then you go into a room where there’s a tiny Vuillard and it’s the greatest fucking thing you’ve ever seen. Now, I love Visconti. Miklós Jancsó, I’ve only seen one, a movie I love called The Red and the White (1967). But there are a lot of other movies. A Woman Under the Influence (1974) is not 100,000 cameras running across the sand. It’s a woman in a room. And that’s one of the best movies I’ve ever seen. So I greet that news with some degree of heartbreak.

NP: Oh, I’m very conflicted about this idea that largesse and grand gestures have somehow become synonymous with the cinematic as opposed to, say, the televisual.

JG: Problem is, it’s one size doesn’t fit all… I’ve quoted this many times, but cinema is part truth, part spectacle. I always sort of adhere to that. But then I’ll see a movie that’s so intimate that blows my mind. I’ve become very aware of the change. The pandemic sped it up, but it was already in motion.

[The hamburgers arrive.]

JG: Oh, there’s cheese on this. That’s great! I forgot to ask for it, what a happy surprise. I can’t eat the bun, but this is really quite a meal. [Mr.Gray indicates a small elastic tie on his upper arm] Now this is totally Hollywood, but I’m going to go to the bathroom and take off this tie because I got this vitamin D12 shot to take in my arm. It’s driving me up the fucking wall. I had this weird IV with zinc, V12, vitamin C, all this shit. I have to make this big Europe trip starting tomorrow and they told me I should get this. Have you heard of this before?

NP: I have not. It sounds like you’re like Led Zeppelin on tour in 1975.

JG: Well, without the bevy of underage chicks. [Looks at hamburger] Wow, that’s great!

WAITRESS: Do you want me to take the bun?

JG: Certainly I do, I really want the bun, but you should take it so I’m not tempted. I’m sure it’s delicious but, you know… Old Jew.

[Mr. Gray returns; takes a bite of hamburger] Wow, that’s so fucking good. You know what makes it? There’s a relish or some fucking thing. I do a gourmet Big Mac with relish kind of like this. I haven’t done it now for three years, because life sucks, but before the pandemic we had a lot of dinner parties, which is something I really love to do. One night I had a bunch of guests over and they said, “What are we having tonight?” And I said, “Big Macs!” I got the bread from a bakery that made me like the sesame seed bun, and I carved off the middle part, what they call the crown. I went online and started reading about the strategy behind the special sauce, the whole thing. The man’s name was Dan Coudreaut. He was the Executive Chef of McDonald’s. I got like organic iceberg lettuce. The one cheat was that I sautéed the onion pieces in a truffle oil, which was really amazing. But everything else was like a Big Mac with incredible ingredients and people were like, “It’s the best thing we’ve ever had.” You know, a Big Mac should not be ecologically possible. There’s a bunch of things in there that shouldn’t be at harvest at the same time, so it’s a true life pleasure.

NP: Thanks to the miracle of modern agriculture.

JG: Okay, do we have to talk about bullshit? Do we have to talk about me?

NP: It’d be nice if occasionally we sort of wandered into the subject.

JG: I don’t have anything to say, dude. It’s like the Woody Allen subtitle, “I feel like FM radio,” you know? I got nothing. If you want to ask me a question, I’ll answer. I’m going to drink the rest of my old fashioned, I’ll tell you everything. How are the fries?

NP: They’re very good.

JG: Fuck you. Just you fucking wait. [Mr. Gray has earlier revealed he is on a no-carb diet.] How old are you?

NP: I just turned 42.

JG: You got another eight years.

NP: The eyes are starting to go.

JG: My eyes are garbage. I can’t see! What’s going to happen is, you’re going to go on a date to your favorite restaurant and you won’t be able to read the menu. That’s the beginning of the end. I can’t operate camera anymore. I used to do it on all the handheld shots. Never let anybody else. I can no longer adequately see through the viewfinder. You know how much that pisses me off?

NP: You’ll wind up pulling a Kurosawa. Just stone blind on the set of Ran (1985).

JG: I’m not quite that bad. But Lord knows I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s in my future. It’s like, what’s that movie, Hollywood Ending (2002)?

NP: The Woody Allen movie?

JG: Yeah. It has one moment in it which is the greatest thing I’ve ever seen. It’s a shot of Treat Williams watching the movie that Woody’s character has made while blind. And the expression on Treat Williams’s face is not, “Holy shit, this sucks”… It’s, “Is this good?”… because he’s totally vapid and has no idea of what is good. It’s incredibly funny.

NP: If I’m not mistaken, this is the movie in which Woody has sort of a degenerate, spiky-haired, weirdo punk rocker son called Scumbag X. It is very funny because it tells you that this is a guy who just so clearly has not paid any attention to any aspect of youth culture for decades, who thinks: “Kids today, they’re named things like… Scumbag X.” I don’t know if it’s a gag, exactly, but it makes me laugh quite a lot.

JG: Okay, what do you want to ask me, Nick Pinkerton? You saw the film yesterday? And you’re still willing to do this fucking talk?

NP: Yeah, man!

JG: Yeah, here’s what you should do. You see the movie two months before, because then, if you hate the movie, you can cancel. You see the way that works? I am trying to teach you the way that this functions.

NP: James Gray. I’m very good at my job. I know Jimmy Gray is my guy. And that this man is going to have some interesting things to say about whatever he’s made. And I should warn you, this is a thing Marc Maron will say to you—I know it not from hearing it myself, because I’ve never heard a podcast, but from the fact that I’ve seen it on social media. He will ask you, “Who are your guys?” and, I think, you’re meant to then answer with the names of people who are very important to you, and inspire you. So I can give you that information, and then you can go in and be prepared to answer the question about who your guys are?

JG: I don’t really have any guys, do I?

NP: You have been known to watch a film.

JG: But I used to have guys… My viewing has become very weird lately, over the last few years. Like I went through a phase of watching Pre-Code Hollywood movies. I’m obsessed with this movie Other Men’s Women (1931).

NP: Absolute masterpiece. That incredible sequence in which Cagney strips his overalls off and sashays into the dancehall…

JG: And then the guy himself is blind, in the rain and the dark… And the ending with no music.

Jeremy Strong and Anne Hathaway in Armageddon Time (2022)

NP: You know, it’s very funny you bring up Wellman because, having just seen Armageddon Time, I was thinking about films in which you see young, adolescent kids express a real sense of solidarity towards one another that has a peculiar sweetness that I just don’t think is possible after you get a little older and more cynical. In Wild Boys of the Road (1933), there’s a scene where Frankie Darro goes to sell his jalopy off to raise some money for his family, and his buddy sees him walking dejectedly off the lot and he stops him and goes, “You know I’m with you, right?” It just slaughters me.

JG: It’s a beautiful movie. He was a great director, that guy.

NP: Those Pre-Code films have an incredible energy… Night Nurse (1931) I love enormously.

JG: What’s the World War I one? Heroes for Sale (1933)! Richard Barthelmess. Loretta Young, who I love. This movie is fantastic. And you know what else I’m obsessed with these days? And you’re one of the only people on planet Earth with whom I can speak about this: Valerio Zurlini. You ever seen Girl with a Suitcase (1961)?

NP: Yeah, yeah!

JG: That movie is amazing. The dude is massively underrated.

NP: Hey, preacher meet choir.

JG: We haven’t talked about my movie at all.

NP: You said you didn’t want to talk about it! You’ve been spinning your wheels talking about everything else on the planet.

JG: Go on, ask me anything. I am supposed to try and sell the fucking thing, aren’t I? What do you want to know about it?

NP: Well God damn, I’m spun out now.

JG: You’re the opposite. You got me vulnerable.

NP: One thing I immediately thought about while watching the film was when I first met you in Marrakesh, I was with my friend, Staten Island native Eric Hynes, and you guys were doing the New York thing where you talk New York stuff. And at one point you casually tossed off the line, “Yeah. My parents thought I was slow. They wanted to send me to City-as-School so I could play with a turtle.”

JG: That’s absolutely true. They thought I was. I put it in the movie! The principal said I was slow.

[Pulls out phone] My brother just found this, let me find this picture. My dad died about two months after I finished shooting. Only now my brother has been able to go through all these photos that he had. This is the year before, this is 1979, a close-up of the class picture. That’s me. And that’s the kid I based Johnny on. Look at his expression, isn’t that amazing? A 1979 public school photo. I tried to find 1980…

But that, that actually happened. We were caught, brought into the principal’s office, he said, “Your son is slow.” I did elide that they were going to send me to City-as-School first, which taught you how to like grout tiles and fix toilets. But I took the entry exam, where I scored—shockingly to them—very high. And that was when my grandfather gave them the money to put me in that school. I love that that’s what you gravitated towards…

I think New York’s become a much darker place than it was. I was last living here in 2012. I came back to make the latest film I made. I was like, this is cool, it’s like the ’70s are back. Except that the mom-and-pop stores are not back. That’s what I miss. Today, it’s like a fucking Walgreens… I mean, I’m being a little bit facetious. Central Park [in the ’70s] was a garbage pit of violence and dirt.

NP: Well it was commanded by this terrifying gang, the Baseball Furies.

JG: Oh, exactly, as Walter Hill would tell it. No, but it was really awful. You went into the subway, right—although this is a funny story in relation, because you just saw the movie. So there is the scene in a subway. Okay, so we got a subway on the MTA, which ran from Bleecker to one of the stations not used, about a two-minute run where we could shoot the scene. They give me a train. They said, [impersonating blasé MTA employee with thick Noo Yawk accent] “Don’t worry, Mr. Gary, we have the best train for you, 1974.” I say, “That’s great, thank you so much.” The train comes in. “Mr. Gary, here’s your 1974 train.” Comes in. Spotless. Spotless, not a single… So I said, “Okay. Well, this is great, guys.” “Yeah, you can put in all the advertising you want from the ’70s, Mr. Gary.” So the production team comes in and they put in all vintage ads. I said, “But yeah now have to cover it with graffiti because that’s what it was. And we have to make sure the light is way darker because it would be really underexposed and fucked up.” “Mr. Gary, the MTA does not approve of, sanction, condone any form of heretofore graffitification under Code M-13.2…” Every train I was on was covered with graffiti. They wouldn’t let us do it. They would not. They wouldn’t even let me do it on tracing paper that you’re going to peel right off. So every bit of that is CGI.

NP: Fuck.

JG: That sequence was so expensive. The whole movie was 15 and a half million bucks, half the fucking money went to putting fucking graffiti on the walls. Because, you went down there, the subway was like a dungeon. The message that sent was: the city is in chaos, it is falling apart. The message was: the city doesn’t care about you. You wander the trains by yourself, we don’t care about you.

NP: I don’t know if you’ve ever seen this 1985 James Glickenhaus film The Protector? It’s not Jackie Chan’s first American movie but it’s one of his pre-Rush Hour attempts to break the US market. And this will be of particular interest to you, there’s a wonderful shot where Jackie Chan is in a bar urinal, and very clearly visible behind him, to the degree that it is somewhat distracting, somebody has written in marker “Save Russian Jews.” Which apparently was a ubiquitous graffiti at some point in the middle 1980s.

JG: I should know the answer to that because that was my moment. I don’t remember that. Save Russians Jews? I remember this whole like Russian Jewry cause, but the major immigration was 1979 for Russian Jews. That was when Brezhnev let a lot of them go. I didn’t come across it, though, I don’t remember that as graffiti. Now you got me wondering.

NP: I can only present the documentary evidence of one shot, and it can be found in The Protector.

But, returning for just a tiny moment to Armageddon Time, it’s impossible not to watch the movie without thinking at times, at least for me, about The 400 Blows (1959), because the films have several parallel scenes. But I also knew your film was very autobiographical. So it becomes almost a chicken or egg thing. Is this like The 400 Blows because of the inspiration of The 400 Blows? Or, when you’re a kid in 1980, did you just happen to have certain experiences that correspond to those of a young Truffaut in 1940 Paris?

JG: It’s hard to answer that; it’s a good question. I did steal from that, and of course Zero for Conduct (1933), the whole idea of that classroom, that I stole from the movie. I mean, obviously I was in class—but the idea of opening it in the classroom, seeing that asshole teacher, all that was stolen from that. I tried not to steal other things. I mean, I’ve had people bring up, which I had totally blocked out, the typewriter thing. But you know, I went back and I watched it again recently because some people have asked me, and I hadn’t seen The 400 Blows in quite some time, so I went back and re-watched it with my children, who loved it. And he brings back the typewriter, which of course I didn’t remember. Léaud tries to bring it back. We had… there was a whole row of Apple II Plus computers, which were actually surprisingly heavy. I remember we didn’t take the monitor. I don’t even know what the fucking idea was, really, a little half-baked. And there was no trying to bring the computer back. Which Antoine Doinel does with the typewriter, it actually makes him more likeable. I wish I had stolen from that. It would have made him a more likeable kid. It would have been bullshit, but…

NP: What I liked very much about the handling of the school material is the slight absurdity of it… Like, what is this school where there’s apparently just this one teacher? There’s a very claustrophobic aspect to it.

JG: That’s what it was. There were 46 kids in the class. 46. When we went on the school trip, which was 6A and 6B, it was almost 100 kids. My friend and I would take off for the day, they had no knowledge that we cut out. Too many kids! It’s hard to communicate. Maybe I should have done a better job of this, but in the late ’70s, in New York, there was such a lack of, like, individual attention… the idea of ADHD, learning differences, nobody talked about any fucking thing like that. My kid goes to school, they got 16 kids in the class. 46 kids were in my class. You know how big that is? In the movie it’s 38; I couldn’t get more kids in the room! I literally couldn’t figure physically how to get more kids in the room while having a camera and crew in there.

Armageddon Time (2022)

NP: Have you ever seen this Paul Morrissey movie Spike of Bensonhurst (1988)?

JG: Yeah, of course.

NP: It’s got the great public school classroom stuff with the bathroom stalls in the classroom.

JG: You really asking me if I’ve seen that film?

NP: I’m sorry.

JG: I’m a little bit insulted… But you know, it’s like Foucault said, school and prison are the same fucking thing. School is prison for kids. That was gym—you took a little beanbag your parents have sewn together with rice in it, you stand in place and throw it up in the air. I didn’t make that up, that was gym.

NP: But in fairness, it’s given you the magnificent physique that you enjoy today.

JG: I’m in better shape now than I was then. I have the resistance bands. And the James Grage—this is true—fitness program. Undersun Fitness.com. The funniest thing ever. Basically, I found out about four years ago that I’m in horrendous shape, and that I’m like, ready to die. So the doctor says you got to take this pill called Lipitor. Statin drugs. I take the drug. After about a month, my bloodwork is like, I don’t know, Stephen Curry or something, I’m incredible. I’m like a fucking high-priced athlete running the court. I’m like, “This is great!” I’m eating pastrami sandwiches! My bloodwork is still incredible!

About a month later, I wake up and my hands are like this. [Makes gesture with hand of fingers stiff and curled in] I say to my wife, “I can’t open my hands. I think I have Lou Gehrig’s disease.” I go to the doctor. I’m like,” I think I have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, I’m going to die.” He goes, “You don’t have that. It’s a side effect of the drug you’re taking. Very rare, but it’s a side effect.” So what do I do? “There’s two things you can do,” he says. “You can come into my office and get an injection every two weeks into your liver.” I’m like, “What, for the rest of my life?” “Yeah, every two weeks. You get an injection, that will do it. Or diet and exercise.” I’m like, “I’ll do diet and exercise.” I did it. I lost 30 pounds. And I do this video program with this guy, James Grage, he’s super buff, tattoos everywhere. I’ve done this for three years. And I’m in fantastic shape. I hate it. I don’t get a bit of endorphin rush. I feel awful. My back hurts. But it works. How about that? Anyway, what else do you want to ask me? Tell me your feelings.

NP: Oh shit, James. Let me pay you a compliment and say that there are a couple of dinner table scenes in Armageddon Time that I found such a delight to watch because, knowing you a little bit, I know you’re a very funny man, but your films have usually been light on what I’d call comic scenes… But the cross-talk at the table, and the bit where the head of the family is blabbering about cantilevered bridges, I was just losing my shit.

JG: Good, that’s what you’re supposed to be doing. Triangles, interlocking triangles!

NP: Yeah, I mean, my father, who was in the sheet metal roofing business in Cincinnati before he retired… this is like verbatim the sort of shit this man loves to talk about: a nice cantilevered bridge… I guess this is universally true of men in certain kinds of professions. Anyways, I was so tickled by these scenes.

JG: Every single thing in there was scripted. There were two cameras. I never called action or cut. I lit with a top light. I would keep doing the scene over and over, and we would move without telling the actors—well they would see that we were moving, but it feels totally improvisational. They just kept repeating lines over and over again in different ways. It was the weirdest way to direct the scenes, but they felt real to me. And I felt they were great. Anthony [Hopkins] didn’t know what was going on. “I thought you were going to call action, Jimmy?” I said, “No, no action, no cut.” “All right, all right then.” And then he got into it.

NP: Is there any other two camera stuff?

JG: Very little. I don’t like two camera generally because you’re sacrificing the light and the composition. But in that I was okay because the way that it was lit—it was just top light, representing the chandelier, about two steps under-exposed, and I knew that I could move everywhere, it didn’t matter. And if the shot compromised the composition I could always move back and get another shot of somebody else. It was a very weird two days, the camera would move around, I was behind the cameras pulling the operators’ ear, this one on this take…

NP: Are you a Robert Aldrich admirer at all?

JG: Yeah, I love Robert Aldrich.

NP: I mention him because from the early ’60s on he was always a two-camera guy. You watch Kiss Me Deadly (1955) or The Big Knife (1955), and they are very visually striking films, they have all these fantastic canted angles… And then, having come to films through TV, I think on Sodom and Gomorrah (1962) first, he starts shooting two cameras, a TV style. And they become ugly films, but what you lose in composition you gain in cadence, in editing—

JG: Exactly, exactly. Actually, we did another scene with two cameras, the assembly. But you see, here’s what I could do that he couldn’t. I could go a little wide, and in the wide shot I could paint out the camera… The reason I did that was because I only had Jessica [Chastain] for one day.

NP: That part [Assistant United States Attorney Maryanne Trump] was initially supposed to go to Cate Blanchett, right?

JG: Yup. She was the first person who got attached to the movie. Covid totally fucked up the schedule. I couldn’t get insurance. We were supposed to go about four months before that, and then Covid pushed me, and it interfered with her shooting Tár (2022). But I still wanted to get a famous actor.

NP: Why did that feel like it had to be somebody—

JG: Because a little boy in that room looked at that person as a god-like figure of great import. And I thought it was important to get a famous person in the room, so everyone who sees that person immediately feels there’s a mythology to them. And the parents I wanted to be stars, too, or recognized, because parents are gods to their children, no matter how inept they are as parents… There is a shot at the end where I’m very high on the kid, where he’s at his desk, and it was because I wanted the idea that Anthony is up here.

NP: It’s interesting when you’re talking about this kind of logic because it’s clear that in a lot of the film you are thinking about subjectivity. Like in the bathroom scene, when the father is pounding on the door. Or the funeral scene, and the perspective on it from the backseat, which is such a bold choice and really, really lovely.

JG: Yeah, [Jeremy Strong] was very disturbed by that because he didn’t have his close-up. He’s going, “The camera’s behind my head!” But that’s how he sees his father, that’s the idea.

NP: What are some points, and I can think of a couple, perhaps, when you felt like you could break from that subjective structuring logic a little bit?

JG: I gave you a glimpse of Johnny’s grandmother. I wanted to try to have the movie say: no matter how much you try, what you think you do, you can’t see into Johnny’s world.

Any more, I think, I couldn’t have gotten away with. And I tried removing that scene, and it made the movie much less. I wanted to indicate, like, you see his world, but is that Paul’s imagination of it, or is it ours? I went there once, to the home of the kid Johnny’s based on, and I tried to recreate it exactly as I saw it. But I wanted the movie to say: you can’t see that side, and you never will. So I broke the rule there.

Where else? There’s a couple moments when the parents are downstairs watching TV and stuff. Not much. Most of the angles are at his level. I tried never to go up here [gestures] without making a point of it. Yes, I was very concerned with making a movie that’s the world of 12-year-old kids.

NP: I’m just always interested in those moments in a movie where somebody has set certain rules into place, and then breaks them. Like in Taxi Driver (1976), I think De Niro’s in every scene, and there’s just this one scene with [Harvey] Keitel, and Jodie Foster—

JG: That scene is really long. It’s a weird point of view. I think he tries to justify it by stitching in footage of De Niro watching the building, right before it. But it’s a very interesting scene, and it’s not in the script, Scorsese did that. I should see it again for that reason. He does it occasionally … But these rules are made to be broken. So that when you break them, there’s an effect of one kind or another.

NP: It has a very different heft, that you’re suddenly in this space, Johnny’s house, that you haven’t seen before.

JG: Exactly. And the idea was, if you use classical terms for a character—what does the character want or dream about? What is his battle against? What is his internal conflict? And of course is he active or passive in some way, or at least trying to be active? I figured if I could answer all these questions for Johnny, I would be partly the way there, because at least in classical terms I always knew somebody was going to have a problem with it. I wanted to be able to answer what his world was like in some way, but in a limited way. So the movie acknowledges that limitation. Because the limitation is not seen as a flaw, I’ve spoken about this. All works of art are limited.

Okay, what else?

“You want the truth? It feels like every movie is my last movie.”

NP: Well, you’ve been very articulate describing the state of the industry.

JG: It’s really sad… The end of movies.

NP: As you’ll recall, there used to be a certain amount of space on studio slates set aside for more artistically ambitious projects—

JG: Zero a year.

NP: Well, now we’re there. Or almost there. And I feel like that has to really change how one who has one of those slots thinks about what they’re doing, because when there are only a handful of people left who are still able to secure a mid-level budget to make for lack of a better term a serious-minded—

JG: Nick, pardon the interruption, but what do you mean when you say mid-budget?

NP: Well, $15 million? I mean, that’s obviously–

JG: Because I consider that low budget. I had 29 days to make the movie. Which was awful. But I’m sorry, go ahead.

NP: Let’s say low budget, then… but you’re still able to attract stars, still able to get a real theatrical roll-out… And there are just a handful people who are still able to do that in the US now, and infrequently. And since we were talking about the pleasures of Pre-Code films: a William Wellman would be cranking out, five, six films a year sometimes, like in 1930 to ’33. And now everything, every project, has become so rare and so precious. How do you think that impacts how you approach filmmaking, when you’re no longer one of many participants in a crowded field and an active economy? You have to have a consciousness, suddenly, of standing for a certain way of making films, which must be daunting.

JG: You want the truth? It feels like every movie is my last movie. I haven’t said this publicly because I don’t want to sound like a Debbie Downer but people say, “Why now? Why did you make this now?” Because I’m not ever going to be able to do it again. I’m in terror, I’m never going to be able to do it again. So I said, “Well, I may as well do this thing about 1980, because I thought that’s when the country started going to shit. And it’s a meaningful moment, with my grandfather and my friend, why not? I’ll never be able to do it again.” And I think I’m right. Maybe I’ll be able to do like Netflix stuff. I’ll be able to do some films that have a higher action profile, maybe a big star. But nothing like this.

NP: And theatres?

JG: I think it is done, I think it is over. I hope I’m completely wrong. Let me tell you, I’ve been horrendously accurate in my predictions about how this would go, from 25 years ago. I said the movies are like opera. You can see where they’re going. If you look at opera, they went through this movement of verismo, which started with Emile Zola, Mascagni, and Puccini. Kind of realism in opera, sort of like the New Hollywood was here. And then after that, they turned to giant spectacles—fascist spectacles, like Nerone, which was Mascagni’s giant fascist opera—huge spectacles after Puccini’s death in 1925. And then, in a five-year period, opera was over, done, dead. You’re witnessing something quite monumental. Now, it may be that the cinema and video games meet in some strange place, and evolve in some way that I can’t picture yet. That is altogether plausible. But the idea of sitting in a theatre with 150 people, 200 people, in a totally passive role—in other words, looking into the window of another person… is over.

Now the problem is, for the creative person… I’m quite left wing politically, but I’m like an old man lefty. And what I have found is that kind of horseshoe theory; something weird has happened where The National Review will have the same opinion as some supposedly lefty blogger, and they will somehow meet in some weird art-police mode. The artist is caught now in this arena where the right doesn’t want you to produce it for obvious reasons, corporations don’t want you to produce it for obvious reasons, and now you got the art police. So we are fucked as creative people from all sides now. I’m willing to say it, but everybody else feels the same who makes films, everybody.

Now, you look at someone like Philip Guston, you know who that is? You know the story?

NP: I do, yes, yes. I was absolutely aghast at it, and the fact that it wasn’t just one institution who chickened out, but three.

JG: That is an absolute disgrace, and a very big symbol of what has happened. And I’m very upset when my own views are considered somehow not left but moderate. I’m not a moderate, I’m a lefty. But I think, “Let me choose the voices I want to listen to, or read, or paintings I want to look at. Don’t you fucking police what I want to look at.” When you say to Philip Guston, because he has Klan images in his paintings, “It’s unpleasant, it makes me uncomfortable, it triggers me,” whatever—that is art’s purpose. Art is about triggering you, art’s about provoking you, it’s not to make you feel great. So we are in a perilous state where we are being hammered by the usual idiots—these fascists, and people who have all the money, and all those people who don’t want you to produce something that is provocative. And now this weird group that I never heard of before, that’s all of a sudden telling you what you shouldn’t or can’t do. Now, I have not experienced it directly myself. Because I don’t read stuff online, I try to block myself out of it. But the Philip Guston thing was a big deal for me. Our function as creative people is to stir shit up. That’s what we do. That’s our job. Make you uncomfortable and go, “Whoa, that seems a little odd.”

How did you get me on to this? Oh, it’s because you provoked me with the decline in theatrical moviegoing. But they’re all connected. You see? Because when the cinema falls out of the zeitgeist, it’s for a variety of reasons. There are these pressures, corporate pressures—and let me make clear, they are by far more important than what I’m talking about on the other side; they’re way more important, it is asymmetrical, there’s no question. But when you put creative people in an environment in which they are afraid, it doesn’t matter whether it’s right wing or left wing reasons. I have read people legitimately saying we are now in an era where we have to police culture, without a sense of humor about it. To me, that’s devastating.

I don’t know. But I think all of this contributes, because we were always fighting corporations. They were always the problem. They control the purse strings. They told you what you could and couldn’t make. They control the range of distribution and the means of production. That was the battle. You have to trick them, you have to coerce them, you have to convince them. Now, we’re worried about this new group: what will they say? How will they feel? They say, “The movie has the N word in it.” I say, “Well, of course—kids said it over and over again when I was growing up.” The movie is not endorsing that! Well, doesn’t matter. Movies are supposed to reflect who we are and were. Not what we wish we were, not what we wish we could have been. That’s aspirational. So, this is all part of the same stuff about why the cinema has lost its preeminent role.

There’s that scene in The Godfather (1972) in this sort of corporate boardroom, where he says, “In my neighborhood, you leave the drug trafficking to the dark people, they’re all animals anyway, so let them lose their souls.” And Sonny Corleone uses the N word. When I was a kid, when I saw The Godfather the first time, when I was an 11-year-old, my reaction to watching that was not: these are great people. My reaction was: this is a portrait of rot, of ethical and moral rot. It was dark as shit! But it was amazing because it was a reflection. Also, there’s a reason Coppola chose to make it look like a corporate boardroom. And then he makes it explicit, right, in the second one? That was all about how the United States went into Cuba and took everything. And that was American pictures engaging with the systems that create, perpetuate oppression. That’s subversive, that’s amazing! But you need to be frank about it in order to engage. So when we talk about the decline of movies, it’s because people are not educated to question capitalism, on one hand, and they’re also not taught to question capitalism, frankly, now on the other… And I’ve seen, to a frightening degree, supposed intelligentsia doing the bidding of corporations.

NP: I could not concur more.

JG: That is a frightening, frightening concept. Now, why are we talking about this? I didn’t just bring it up. You asked me about the future of cinema, or about the multiplex, all these things, they are all connected, all of them. The reason cinema is dying is not only because of the corporation, which has always presented the catastrophe to us. It’s because now they’ve lost their critical role in the essential dialogue about being who we are—not who we wish we were, who we actually are. Now, am I making any fucking sense at all?

NP: You’re making an enormous amount of sense. In fact paraphrasing most of my own rantings of recent years.

JG: Okay, because I’m drinking too much.

NP: But to your point, I think what is unique about capitalism of the Silicon Valley variety is, as cancerous as various iterations of capitalism have been, at the turn of the last century, you could at least understand Carnegie Steel: “Oh, yeah, they make those I-beams that go in the big tower. They employ, though exploiting them, a great many people.” But the role of someone like Elon Musk is much more difficult to understand: how do you become the richest man in the world when an infinitesimal portion of the population uses anything you make? Similarly, the “invisible hand of the market,” as we were taught to understand it, no longer seems to determine success. The streaming services, much like Uber or Lyft, operate on these loss leader models where they have an infinite amount of capital available to them, which gives them enough runway to burn that they can kill the competition without ever once posting a profit.

JG: There’s definitely a fakery in the bakery thing going on in late stage capitalism. I can’t quite put my finger on it. It’s like over-speculation, I’ve tried to digest it. I don’t know where it leads.

NP: None of these industry disruptors have a sustainable model for making money, they’re just burning money until—

JG: But the jig is up soon.

NP: One hopes!

Share: