Essay

[wpbb post:title]

Essay

BY

Violet Lucca

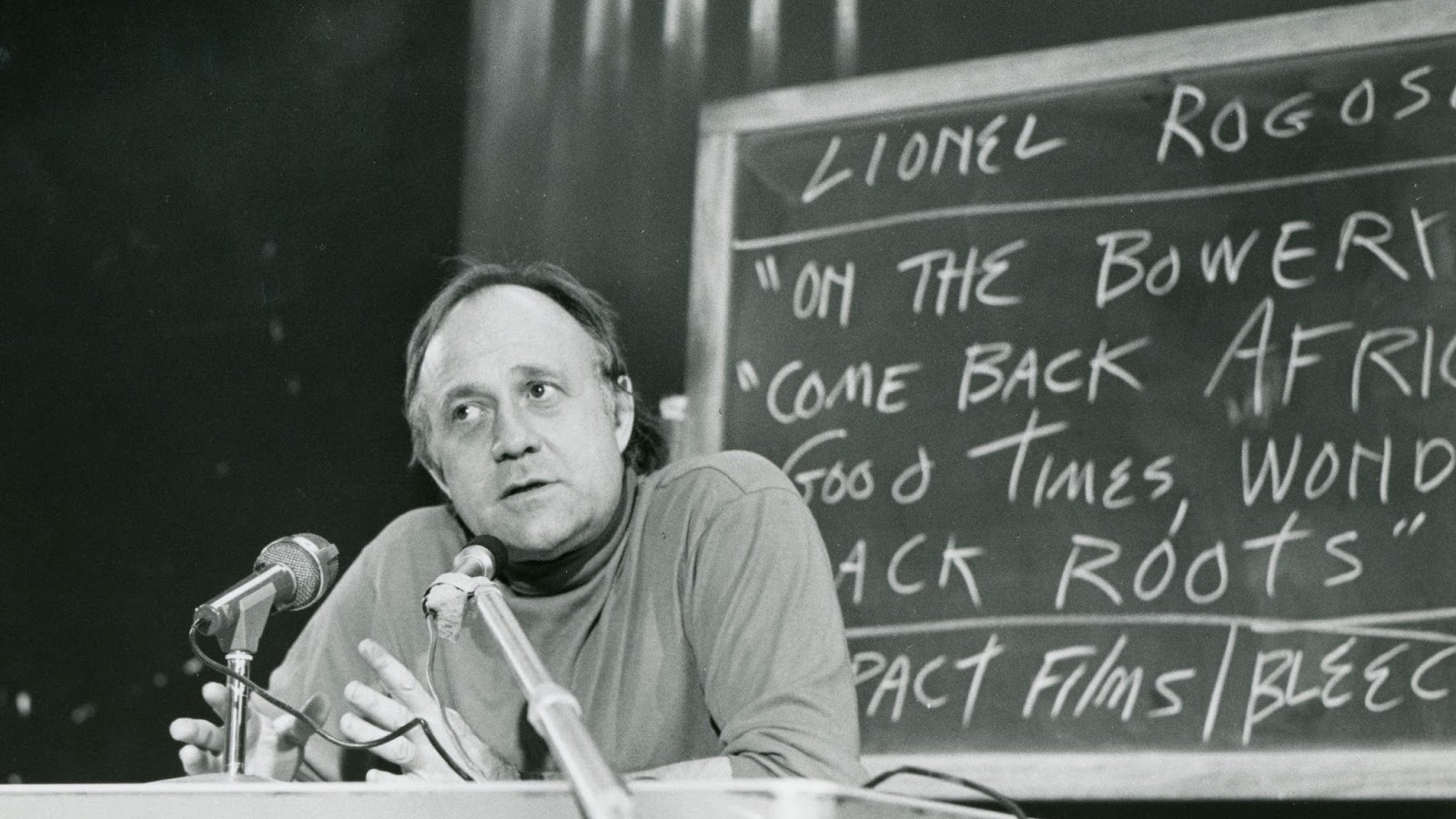

On the hybrid moments of Lionel Rogosin’s radical docs.

Our Lionel Rogosin series plays In Theatre and At Home through May 5.

In the May 5, 1966 edition of Jonas Mekas’s “Movie Journal,” the author, distributor, and filmmaker offers a report of-or, more likely, embellishes upon-a stateside struggle session for Cahiers du Cinéma editor Louis Marcorelles. Mekas, Shirley Clarke, Louis Brigante, and Lionel Rogosin grilled Marcorelles, after he had told the New York Times that there were no young American directors at Cannes because they “are simply not turning out films of more than routine interest.” Like all of Mekas’s writing, the record of these exchanges is kinetic, as if the entire conversation took place in constant motion, a kind of New American Cinema purgatory where the chain-smoking, black-clad crew strode nonstop around the Lower East Side. Mekas arguably casts himself as the hero, or, at least, his statements are the longest, most passionate, and detailed of those reported. But who could blame him for not taking better notes? A weekly column happens every seven days; the chance to straighten out someone in such a position of power who is so absolutely fucking wrong only comes along once in a great while.

To those only nominally familiar with the New American Cinema, the relative silence of Mekas’s posse in these pages may not seem suspect-Brigante is likely an unknown, Clarke is merely Portrait of Jason (1967), and as for Rogosin… well, didn’t he do those well-meaning hybrid documentaries about alcoholics on the Bowery, and that thing with Miriam Makeba? To allow this misconception to endure would be to let the Marcorelles of this world win-Marcorelles being the one, who, per Mekas, said that Scorpio Rising (1963) was “on the verge of what I call commercial cinema”-it is the way of spiritual and intellectual death.

Setting aside any gaps in film history, it can sometimes be difficult to appreciate the radical nature of someone like Lionel Rogosin because we live in a time when everyone is different in the same way, when so many Americans must hold down multiple jobs to survive (and are actively encouraged to do so if they’re within the amorphous category of “creatives”). Rogosin’s choice to leave his father’s profitable textile factory in 1954 in order to pursue social justice through filmmaking-before there was a firm notion of independent American cinema, after Hollywood had expunged the last group of people who deigned to promote leftist ideas through narrative film-was radical. It is not hyperbole to note this.

While On the Bowery (1956) and Come Back, Africa (1959) can impress a contemporary viewer as documents of a time and a place, and as biting indictments of racism, classicism, and capitalism’s failures, these films must also be understood as challenges to what cinematic form, narrative, and function were at the moment of their creation. To lose or forget this is to misunderstand these films. While Rogosin drew inspiration from Robert Flaherty, that frequent bender of fact, the idea that documentary, or docudrama, would serve a political purpose was then novel.

Rogosin was a signatory of the New American Cinema manifesto, but his efforts extended far beyond filmmaking. The Bleecker Street Cinema, which he purchased and founded in 1962 in order to screen Come Back, Africa and other new American independent films, was also part of this commitment to social change. Rogosin intermittently programmed the theater, which was part of a sea change in exhibition without which so much-even the stuff you hate-would not exist. (Bleecker Street was a favorite haunt of Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola, still mere dorky babes, as well as thousands of others interested in expanding their view of the artform.) With all due respect to Mekas, it’s almost certain that Rogosin said more to Marcorelles than was printed in the Village Voice.

On the Bowery (1956)

These films were constructed to change hearts and minds, or at the very least to provoke new thoughts about their equally identifiable targets: the injustices and falsehoods upon which Western societies are built.

Still, the films themselves speak volumes, and it’s impossible to mistake the intent behind Rogosin’s work. These films were constructed to change hearts and minds, or at the very least to provoke new thoughts about their equally identifiable targets: the injustices and falsehoods upon which Western societies are built. Their messages do not feel painfully didactic. Yet they unravel polite, bourgeois notions about war, class, and race, and prove instructional for those on the right and left.

Across his docudramas and later, more conventional-but no less shit-kicking-documentaries, Rogosin creates opportunities for his subjects to have conversations and to tell stories in their own words. “To make the infiniteness of reality exciting and meaningful is unquestionably an artistic process,” writes Rogosin in a manifesto published in a 1960 issue of Film Culture. “Reality-as close as we can come to it-is rarely seen on the screen, but when reality is seen it is strongly felt.” His mastery of rhythm (in conversations and editing), along with his keen eye for composition, makes for truly exciting viewing.

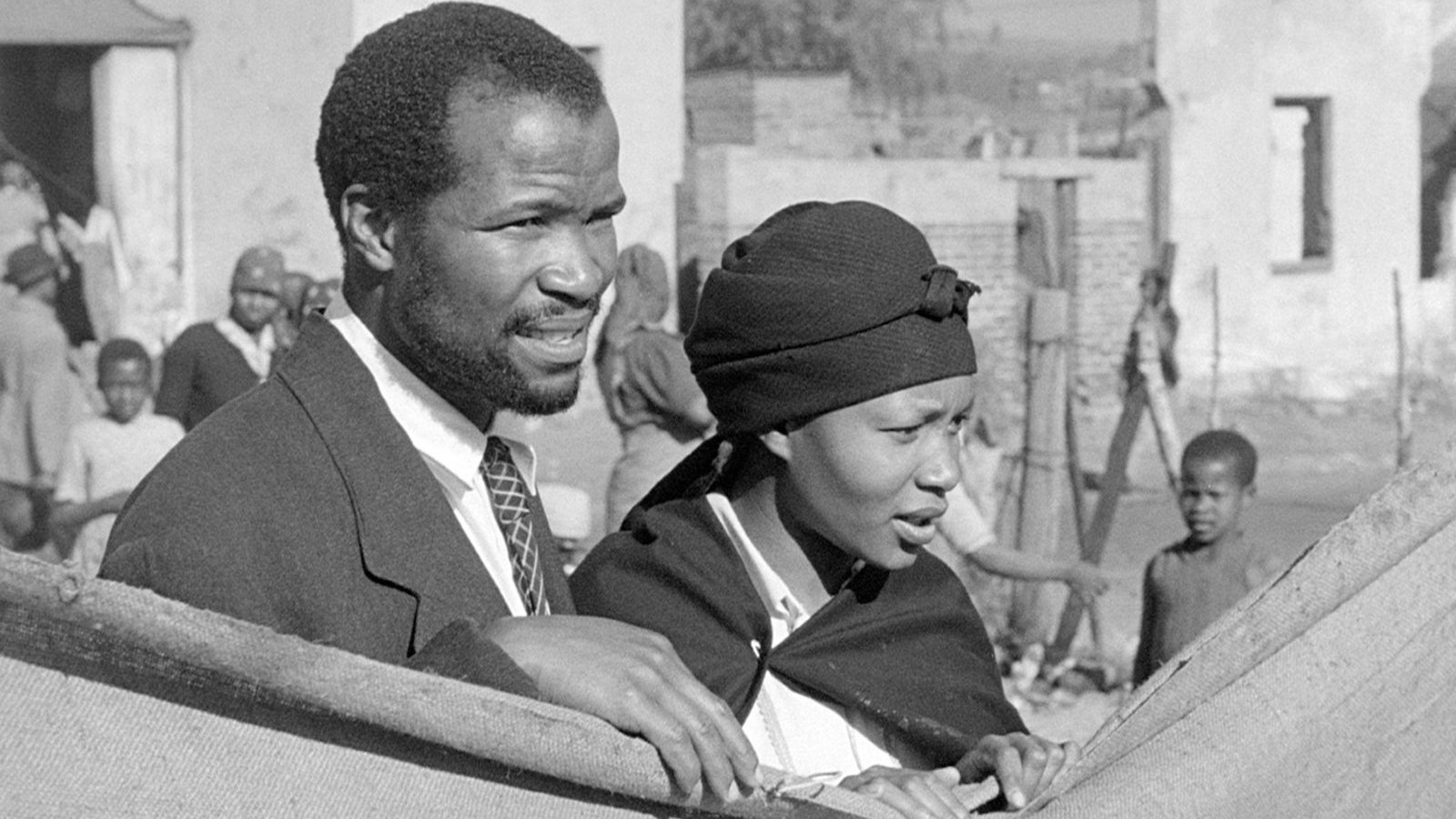

In his early films, this process was perhaps more straightforward. For Come Back, Africa-which had a script outline co-written by Lewis Nkosi and William Modisane, contributors to the South African magazine Drum-the collaborative nature of the resultant work is apparent through the film’s alternately impassioned and brittle dialogue, which was clearly improvised. (The way in which the characters talk over each other is frequently charming, veering between reality and a less-than-perfect imitation.) While the film contains glimpses of how gentile, Jewish, and Indian people fit into the system, the maddening experiences of Black South Africans are up front; when Rogosin cuts to elegantly framed shots of the cityscape at sunrise and dusk, you understand why the young protagonist, Zachariah, remains so enamored of his new surroundings despite apartheid’s dehumanizing control.

In lesser-known later works like Black Roots (1970), Woodcutters of the Deep South (1973), and Arab Israeli Dialogue (1974), Rogosin’s treatment of his subjects grows ever more complicated. Black Roots has a deceptively simple premise: a group of Black activists and musicians sit in a darkened room, talking about their experiences growing up in the South, and play songs whenever the mood strikes them. However, the audio recordings of their discussions plays over footage of Harlem, one of the hubs of the Great Migration. We hear one side of the Black experience, at the same time as we see the (mostly smiling) faces of those living in the fabled North, where supposedly segregation, violence, and open racism don’t exist. What connects these two seemingly divided groups is resilience and resistance.

While Rogosin sometimes uses this footage of Harlem to illustrate issues the group are talking about (such as colorism), the gap between the speaking and silent subjects is often bridged by nondiegetic music. Alan Lomax, the legendary ethnomusicologist, and his wife Anna, served as advisers, and provided field recordings of songs by Memphis Slim, Lead Belly, Vera Hall, and others. These songs, like so much of what Jim Collier, the Reverend Gary Davis, Wendy Smith, Florynce “Flo” Kennedy, Larry Johnson, and the Reverend Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick say, are parts of American history that, at the time, had only recently become known to the non-Black public. (Thanks to the interminable culture wars, this history may be lost to an even higher percentage of the population.)

Come Back, Africa (1959)

These scratchy remnants of cultural history are also paired with contemporary, unapologetically Black music by Ray Charles’s “Georgia on My Mind” and James Brown’s “Say It Loud-I’m Black and I’m Proud,” as well as field recordings of music from Africa, revealing a lineage that survived (and thrived) despite white colonizers’ best efforts. While Black Americans are still routinely discussed as if they are not true Americans, somehow outside or ancillary to the American experience despite having built this country (see any public figure who claims they have “different values” or tosses around the word “thug”), Black Roots powerfully argues that Black people and culture are inextricable from the nation’s history, yet Rogosin’s approach also allows the viewer to get past a limited understanding of what resilience means. It is shown not to be entirely somber, or all fight. “Flo” Kennedy, a pro-choice litigator who was also one of the most famous Black feminists in the country at the time, is given space to lovingly describe her kind mother’s refusal to take any shit from anybody. Away from her usual confines of courtroom, press conference, or rally, we gain a deeper sense of Kennedy-she’s funny, she’s thoughtful, she loves her mom. During Reverend Davis’s performance of “Death Don’t Have No Mercy,” Kennedy is moved to tears. She becomes more than a symbol of oppression, defiance, or an outlier-she is a human being. A simple point, but not a facile one.

Woodcutters of the Deep South, like Black Roots, contains no staged/restaged scenes, and deconstructs received disinformation about the South. Reverend Francis Walters, one of the religious leaders who helped Rogosin gain entry to South Africa, notified the director of the Gulf Coast Pulpwood Association, a fledgling labor organization that included everyone, regardless of race or position in the production chain, involved in the production of paper pulp. All of these workers were essentially freelancers without benefits, who either broke even or netted yearly profits in the neighborhood of $200-including the men who cut trees down in the boiling heat, as well as those who leased or rented axes and trucks from the paper companies for their crews.

James Simmons, a farmer who had gotten into pulpwood during the mid-’60s, formed the group in order to fight such indignity and bargain with these multinationals, and he also served as its larger-than-life head. As Reverend Walters notes somewhat ruefully early on, the prospect of unifying working-class Blacks and whites in the South was exciting to organizers all over the country-but, as continues to be true of many organizing situations, problems arose not only from issues around race but from egos. Simmons opposed holding elections for the organization, and, in the film’s prolonged climax, is confronted by a group of members, advisers, and professional organizers hired to help the union, who argue for the importance of keeping things democratic. Rogosin, for the first time in his filmography, reads narration that sets up the meeting: “As I watched this happening, it seemed to me a pattern that has been happening over and over again since the beginning of history.” This statement proves to be entirely accurate: Simmons tells everyone that some white members of the group expressed concern that, if elections were held, Black members (who vastly outnumbered them) would only vote for fellow Blacks, and threatened to leave; when he is informed that, in fact, one chapter voted in a White man as their leader, Simmons doesn’t have a good answer.

Some of the most illustrative points about class, organizing, capitalism, race, and the South-and the pervasiveness of violence and death-come, however, from stories told by subjects before this meeting. Perhaps the most vivid of these is from Alabaman Bob Zellner, a white former SNCC member turned professional organizer, who tells the story of very nearly getting murdered for attending a “Black” protest in Mississippi. (The peaceful demonstration was a response to a white state legislator killing a Black farmer who wished to vote.) Zellner’s details of his capture, which include being thrown into jail, and his eyeballs almost getting squished, concludes with his description of the noise of a prison cell lock closing as “the sweetest sound I have ever heard.”

In another moment, Simmons explains how the Great Migration harmed the South economically and socially, and how those in charge of the paper companies realised that it was the perfect place to practice reckless, extractive industry. Rogosin also paints Atlanta, the business capital of the South, as an alternately tacky and evil quietus: there is an extended sequence of a downtown hotel, set to Bach’s Toccata und Fuge in D Minor (aka that creepy organ music drop), during which an unseen interviewee tells the story of an acquaintance, who seemingly had everything to live for, leaping off of the top floor and into the lobby. These digressions, some of which turn out to include vitally important information while others simply add character, are relayed in rapid-fire drawls. These speeches can be difficult to parse, and it’s not always easy to understand what the multifarious, wide-sweeping implications are for this region and its people.

Woodcutters of the Deep South (1973)

Made one year later, Arab Israeli Dialogue confronts the not-entirely straightforward, unresolvable issues around land, violence, and prejudice in a place that is known for all three. The representatives of this dialogue get into it almost immediately over what’s actually happening: Palestinian Rashed Hussein (also Romanized as Rashid and Rashad) interrupts Israeli Amos Kenan by saying, “This is not a discussion. This is a meeting between two people who met each other 15 years ago and they are meeting again. They still consider themselves-I consider you-a friend. But I don’t agree with you.”

This alternately hostile and friendly statement encapsulates the many contradictions of Hussein’s brief life. Though the poet was thrown out of the country for his activism against the occupation, he was married to a Jewish woman, spoke Hebrew fluently, and translated many Israeli authors into Arabic (and vice versa). Hussein’s contemporaries described him as exceedingly friendly, even though his poems angrily mourn the loss of his homeland and the Arab world’s complicity in failing to return it to his countrymen. Kenan, like Rashed, had a history of more than mere empathy for those who were supposedly his enemies: he was active in anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist groups, and was once arrested for (and later confessed to) participating in a plot to assassinate Israel’s minister of transportation.

However, none of this context is announced in the film; they are merely identified by name and profession. Their meeting inside the basement of the Bleecker Street Cinema is shot in black and white, as if to mock those who dare oversimplify the Israel-Palestine issue. Kenan’s arguments for the Jews’ right to remain, largely predicated upon the centuries of anti-Semitism they had faced in the West, are irrefutable-but so are Hussein’s pleas that the debt owed to the Jewish people should not be paid by Palestinians. Throughout, Kenan makes clear that his idea of Zionism differs from his state’s version, and shoots down Hussein’s notion of human rights (one man, one vote) by citing the situation of Black Americans. At times, their philosophical-emotional-historical parrying plays over scenes of the land they desire and defend: the curve of the landscape, children, and an unidentified paramilitary group of smiling soldiers. By the end, weariness and regret is visible on both of their faces, and it’s clear that emotions, not just concepts, are weighing heavily on Kenan. Perhaps it’s because he has an official state and Hussein does not that the Israeli sends up a flare of optimism. “It takes more than 25 years to get used to each other,” he says. We, however, are burdened with the painful knowledge that it takes more than 50.

Rogosin would never make another film after Arab Israeli Dialogue, but not for lack of trying. The director died in December of 2000, a few short years before the inexpensiveness and ease of digital filmmaking revolutionized the documentary field. (As someone who was alive and seeing movies in the early 2000s, I can attest that George W. Bush’s godawful administration also fanned the flames of this boom.) One gets the sense of the work Rogosin would have produced had he lived through the horrors of Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay, the surveillance state, or the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in his lone saturnine film, Good Times, Wonderful Times (1965). Much of the footage of war and violence that Rogosin uses throughout-which includes men going over the top in WWI to radiation-sick survivors of Hiroshima to Stalingrad-was collected over a two-year period, across 12 countries, with collaborator James Vaughan, much of which was previously unseen. Over the course of its runtime, the tension gradually heightens. “War is one way of keeping the population down,” a sharp-suited Anglo confidently informs his fellow partygoers, huddled together in a posh, seemingly never-ending flat, late in the film; soon after, his sound bite repeats over a photo of two boys caught on the barbed wire fence of a concentration camp.

“War is one way of keeping the population down,” a sharp-suited Anglo confidently informs his fellow partygoers, huddled together in a posh, seemingly never-ending flat, late in the film; soon after, his sound bite repeats over a photo of two boys caught on the barbed wire fence of a concentration camp.

Yet, across the film, Rogosin shows that misrepresentation and obnoxious certitude are more effective tools than propaganda. All of the young men attending this party had done their National Service, an 18-month period of conscription that (save for those whose obligation overlapped with imperial ambitions in Cyprus, Korea, Kenya, Malaysia, and in the Suez) consisted of military training and building infrastructure at home. Rogosin’s juxtapositions make clear that the false confidence this experience generates-or, conversely, the blithe bloodlust from those who saw action and killed people-is poisonous. While exposing the arrogance of these well-heeled partygoers (which is revealed to not be exclusively a heterosexual, cis male trait) seems easy game, the sustained effect of contrasting scenes of pointless death and brutality with this boozy milieu weighs heavily on the privileged, and asks you to rethink the dumb shit you might blurt out at a party.

Rogosin showed Good Times, Wonderful Times across college campuses all over the country because no distributor would touch it; it was one of several endeavors that he lost money on. As a visionary advocate for the medium, Rogosin’s refusal to compromise was always in the service of others. How else would anyone see these people, these injustices, these atrocities? The marginalized individuals he gave voice in his films to were always shown as part of something larger than themselves, for better or worse. It’s the moment in Black Roots when Larry Johnson admits that he still hangs on to colorism because of whom his grandmother advised him not to marry; the cumulative effect of the stories told about James Simmons that make clear he was an asshole with good ideas and (probably) good intentions; or how Amos Kenan slides from exuding boisterous confidence about the Dead Sea Scrolls to making a chastened admission that, like the Jews, Arabs have a right to fight for their homeland. In a world where art so frequently talks down to its audience, whether because they’re dumb, distracted, or both, one need merely be human to reap the rewards of Rogosin’s films.

Violet Lucca is the web editor at Harper’s Magazine, and is the host of their podcast. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Art in America, Sight and Sound, Film Comment, and elsewhere.

Black Roots (1970)